For average wage earners in Russia, it's a big payday. For criminals seeking to escape the harsh conditions and abuse in prison, it's a chance at freedom. For immigrants hoping for a better life, it's a simplified path to citizenship.

All they have to do is sign a contract to fight in Ukraine.

Click to Gallery

FILE - People walk past an army recruiting billboard with the words "Military service under contract in the armed forces," in St. Petersburg, Russia, March 24, 2023. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - Recruits carry their gear at a military recruitment center in Rostov-on-Don, Russia, Oct. 31, 2022. (AP Photo, File)

FILE- Recruits carry ammunition during training at a firing range in the Rostov-on-Don region of southern Russia, Tuesday, Oct. 4, 2022. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - A street performer walks past a patriotic billboard showing a Russian serviceman and the slogan "The Motherland that we defend" in St. Petersburg, Russia, March 14, 2023. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - Russian recruits take a train at a railway station in Prudboi in the Volgograd region of Russia, Sept. 29, 2022. (AP Photo, File)

As Russia seeks to replenish its forces in nearly four years of war — and avoid an unpopular nationwide mobilization — it's pulling out all the stops to find new troops to send into the battlefield.

Some come from abroad to fight in what has become a bloody war of attrition. After signing a mutual defense treaty with Moscow in 2024, North Korea sent thousands of soldiers to help Russia defend its Kursk region from a Ukrainian incursion.

Men from South Asian countries, including India, Nepal and Bangladesh, complain of being duped into signing up to fight by recruiters promising jobs. Officials in Kenya, South Africa and Iraq say the same has happened to citizens from their countries.

President Vladimir Putin told his annual news conference last month that 700,000 Russian troops are fighting in Ukraine. He gave the same number in 2024, and a slightly lower figure – 617,000 – in December 2023. It's unclear if those numbers are accurate.

Still hidden are the numbers of military casualties, with Moscow having released limited official figures. The British Defense Ministry said last summer that more than 1 million Russian troops may have been killed or wounded.

Independent Russian news site Mediazona, together with the BBC and a team of volunteers, scoured news reports, social media and government websites and collected the names of over 160,000 troops killed. More than 550 of those were foreigners from over two dozen countries.

Unlike Ukraine, where martial law and nationwide mobilization has been in place since the start of Russia's full-scale invasion in February 2022, Putin has resisted ordering a broad call-up.

When a limited mobilization of 300,000 men was tried later that year, tens of thousands of people fled abroad. The effort stopped after a few weeks when the target was met, but a Putin decree left the door open for another call-up. It also made all military contracts effectively open-ended and barred soldiers from quitting service or being discharged, unless they reached certain age limits or were incapacitated by injuries.

Since then, Moscow has largely relied on what it describes as voluntary enlistment.

The flow of voluntary enlistees signing military contracts has remained strong, topping 400,000 last year, Putin said in December. It was not possible to independently verify the claim. Similar numbers were announced in 2024 and 2023.

Activists say these contracts often stipulate a fixed term of service, such as one year, leading some potential enlistees to believe the commitment is temporary. But contracts are automatically extended indefinitely, they say.

The government offers high pay and extensive benefits to enlistees. Regional authorities offer various enlistment bonuses, sometimes amounting to tens of thousands of dollars.

In the Khanty-Mansi region of central Russia, for example, an enlistee would get about $50,000 in various bonuses, according to the local government. That's more than twice the average annual income in the region, where monthly salaries in the first 10 months of 2025 were reported to be just over $1,600.

There also are tax breaks, debt relief and other perks.

Despite Kremlin claims of relying on voluntary enlistment, media reports and rights groups say conscripts — men aged 18-30 performing fixed-term mandatory military service and exempted from being sent to Ukraine — are often coerced by superiors into signing contracts that send them into battle.

Recruitment also extends to prisoners and those in pretrial detention centers, a practice led early in the war by the late mercenary chief Yevgeny Prigozhin and adopted by the Defense Ministry. Laws now allow recruitment of both convicts and suspects in criminal cases.

Foreigners also are recruiting targets, both inside Russia and abroad.

Laws were adopted offering accelerated Russian citizenship for enlistees. Russian media and activists also report that raids in areas where migrants typically live or work lead to them being pressuring into military service, with new citizens sent to enlistment offices to determine if they’re eligible for mandatory service.

In November, Putin decreed that military service was mandatory for certain foreigners seeking permanent residency.

Some reportedly are lured to Russia by trafficking rings promising jobs, then duping them into signing military contracts. Cuban authorities in 2023 identified and sought to dismantle one such ring operating from Russia.

Nepal’s Foreign Minister Narayan Prakash Saud told The Associated Press in 2024 that his country asked Russia to return hundreds of Nepali nationals who were recruited to fight in Ukraine, as well as to repatriate the remains of those killed in the war. Nepal has since barred citizens from traveling to Russia or Ukraine for work, citing recruitment efforts.

Also in 2024, India’s federal investigation agency said it broke up a network that lured at least 35 of its citizens to Russia under the pretext of employment. The men were trained for combat and deployed to Ukraine against their will, with some "grievously injured,” the agency said.

When Putin hosted Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi for talks in 2024, New Delhi said its nationals who were “misled” into joining the Russian army would be discharged.

Iraqi officials say about 5,000 of its citizens have joined the Russian military along with an unspecified number who are fighting alongside Ukrainian forces. Officials in Baghdad cracked down on such recruiting networks, with one man convicted last year of human trafficking and sentenced to life in prison.

An unknown number of Iraqis have been killed or gone missing while fighting in Ukraine. Some families have reported that relatives were lured to Russia under false pretenses and forced to enlist; in other cases, Iraqis have joined voluntarily for the salary and Russian citizenship.

Foreigners duped into fighting are especially vulnerable because they don’t speak Russian, have no military experience and are deemed “dispensable, to put it bluntly,” by military commanders, said Anton Gorbatsevich of the activist group Idite Lesom, or “Get Lost,” which helps men desert from the army.

This month, a Ukrainian agency for the treatment of prisoners of war said over 18,000 foreign nationals had fought or are fighting on the Russian side. Almost 3,400 have been killed, and hundreds of citizens of 40 countries are held in Ukraine as POWs.

If true, that represents a fraction of the 700,000 troops that Putin said are fighting for Russia in Ukraine.

Using foreigners is only one way to meet the constant demand, said Artyom Klyga, head of the legal department at the Movement of Conscientious Objectors, noting Russian recruitment efforts appear to be stable. Most of those seeking help from the group, which assists men in avoiding military service, are Russian citizens, he said.

Kateryna Stepanenko, a Russia researcher at the Washington-based Institute for the Study of War, said the Kremlin has gotten more “creative” in the last two years with attracting enlistees, including foreigners.

But recruitment efforts are becoming “extremely expensive” for Russia, which faces a slowing economy, she added.

—

Associated Press writers Gerald Imray in Cape Town, South Africa, and Qassim Abdul-Zahra in Baghdad contributed.

FILE - People walk past an army recruiting billboard with the words "Military service under contract in the armed forces," in St. Petersburg, Russia, March 24, 2023. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - Recruits carry their gear at a military recruitment center in Rostov-on-Don, Russia, Oct. 31, 2022. (AP Photo, File)

FILE- Recruits carry ammunition during training at a firing range in the Rostov-on-Don region of southern Russia, Tuesday, Oct. 4, 2022. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - A street performer walks past a patriotic billboard showing a Russian serviceman and the slogan "The Motherland that we defend" in St. Petersburg, Russia, March 14, 2023. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - Russian recruits take a train at a railway station in Prudboi in the Volgograd region of Russia, Sept. 29, 2022. (AP Photo, File)

LAKSHMIPUR, Bangladesh (AP) — A labor recruiter persuaded Maksudur Rahman to leave the tropical warmth of his hometown in Bangladesh and travel thousands of miles to frigid Russia for a job as a janitor.

Within weeks, he found himself on the front lines of Russia’s war in Ukraine.

An Associated Press investigation found that Bangladeshi workers were lured to Russia under the false promise of civilian work, only to be thrust into the chaos of combat in Ukraine. Many were threatened with violence, imprisonment or death.

AP spoke with three Bangladeshi men who escaped from the Russian military, including Rahman, who said that after arriving in Moscow, he and a group of fellow Bangladeshi workers were told to sign Russian documents that turned out to be military contracts. They were taken to an army camp for training in drone warfare techniques, medical evacuation procedures and basic combat skills using heavy weapons.

Rahman protested, complaining that this was not the work he agreed to do. A Russian commander offered a stark reply through a translation app: “Your agent sent you here. We bought you."

The three Bangladeshi men shared harrowing accounts of being coerced into front-line tasks against their will, including advancing ahead of Russian forces, transporting supplies, evacuating wounded soldiers and recovering the dead. The families of three other Bangladeshi men who are missing said their loved ones shared similar accounts with relatives.

Neither the Russian Defense Ministry, the Russian Foreign Ministry nor the South Asian country’s government responded to a list of questions from AP.

Rahman said the workers in his group were threatened with 10-year jail terms and beaten.

“They’d say, ‘Why don’t you work? Why are you crying?’ and kick us,” said Rahman, who escaped and returned home after seven months.

The workers’ accounts were corroborated by documents, including travel papers, Russian military contracts, medical and police reports, and photos. The documents show the visas granted to Bangladeshi workers, their injuries sustained during battles and evidence of their participation in the war.

How many Bangladeshis were deceived into fighting is unclear. The Bangladeshi men told AP they saw hundreds of Bangladeshis alongside Russian forces in Ukraine.

Officials and activists say Russia has also targeted men from other African and South Asian countries, including India and Nepal.

In the lush greenery of the Lakshmipur district in southeast Bangladesh, nearly every family has at least one member employed as a migrant worker overseas. Job scarcity and poverty have made such work essential.

Fathers embark on yearslong journeys for migrant work, returning home only for fleeting visits, just long enough to conceive another child, whom they will likely not see again for years. Sons and daughters support entire families with income earned abroad.

In 2024, Rahman was back in Lakshmipur after completing a contract in Malaysia and seeking new work. A labor recruiter advertised an opportunity to work as a cleaner in a military camp in Russia. He promised $1,000 to $1,500 a month and the possibility of permanent residency.

Rahman took out a loan to pay the fee of 1.2 million Bangladeshi taka, about $9,800, to the broker as a fee. He arrived in Moscow in December 2024.

Once in Russia, Rahman and three other Bangladeshi workers were presented with a document in Russian. Believing it was a contract for cleaning services, Rahman signed.

Then they went to a military facility far from Moscow, where they were issued weapons and underwent three days of training, learning to fire, advance and administer first aid. The group went to a barrack near the Russia-Ukraine border and continued training.

Rahman and two others were then sent to front-line positions and ordered to dig pits inside a bunker.

“The Russians would take a group of say, five Bangladeshis. They would send us in front and stay at the back themselves,” he said.

The men stayed in a leaky bunker in the rain as bombs fell a few kilometers away. Missiles flew overhead.

One person was serving food. "The next moment, he was shot from a drone and fell to the ground right there. And then he was replaced,” Rahman said.

Some Bangladeshi workers were lured into the army with promises of positions far from the front line.

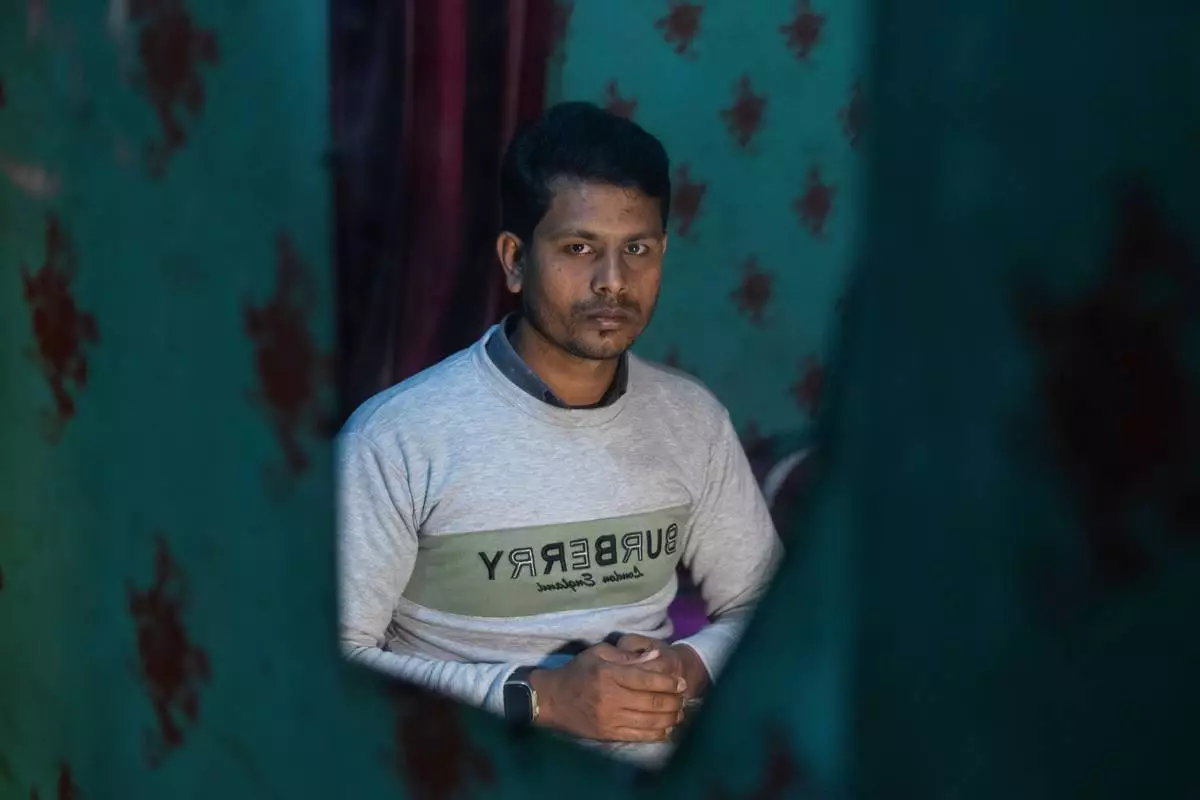

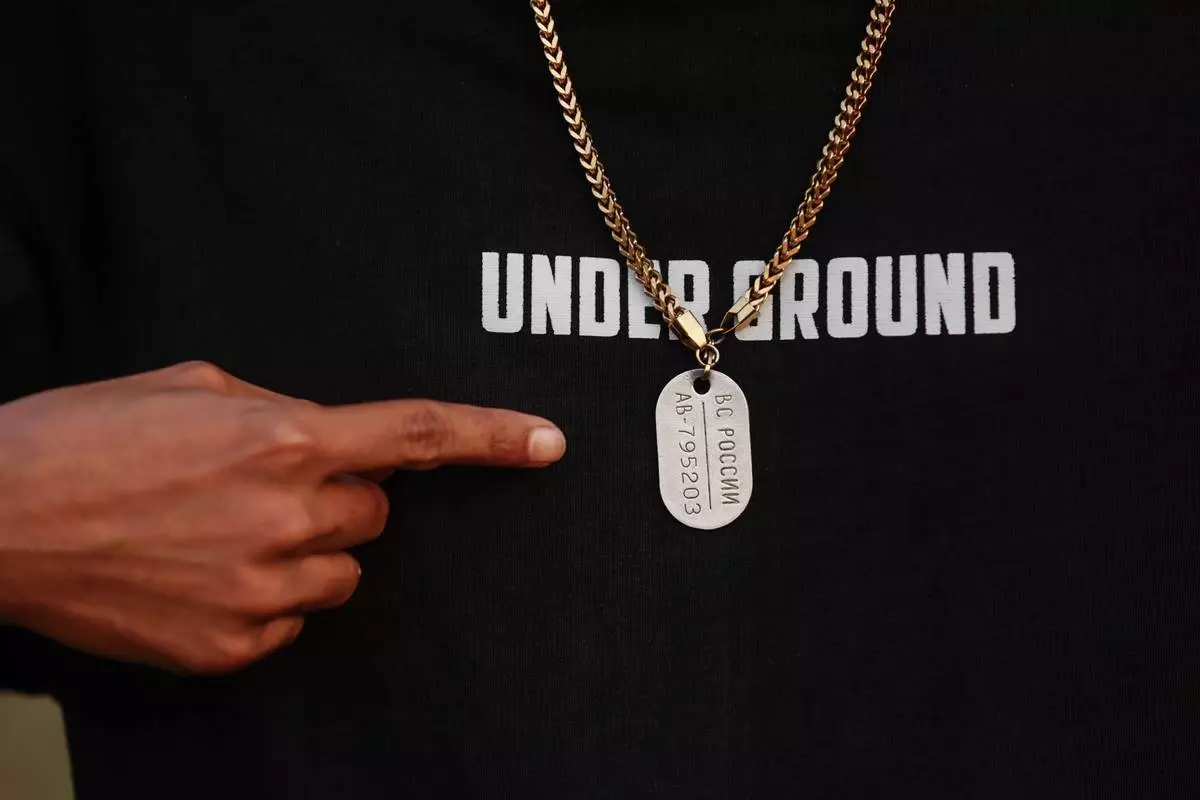

Mohan Miajee enlisted in the Russian army after the job that initially brought him to Russia — serving as an electrician for a gas-processing plant in the remote far east — was plagued by harsh working conditions and relentless cold.

While searching for employment online, Miajee was contacted by a Russian army recruiter. When he expressed his reluctance to kill, the recruiter said his skills as an electrician made him an ideal candidate for an electronic warfare or drone unit that would be nowhere near combat.

With his military papers in order, Miajee was taken in January 2025 to a military camp in the captured city of Avdiivka. He showed the camp commander documents describing his experience and explained that his recruiter had instructed him to ask for “electrical work.”

“The commander told me, ‘You have been made to sign a contract to join the battalion. You cannot do any other work here. You have been deceived,’” he said after returning to his village of Munshiganj.

Miajee said he was beaten with shovels, handcuffed and tortured in a cramped basement cell, and held there every time he refused to carry out an order or made a small mistake.

Because of language barriers, for example, "if they told us to go to the right and we went to the left, they would beat us severely,” he said.

He was made to carry supplies to the front and collect dead bodies.

Meanwhile in Rahman's unit, some weeks later, they were instructed to evacuate a Russian soldier with a wounded leg. The men carried him, but no sooner had they left the position than they saw a Ukrainian drone buzzing above. It fired at them. Then more drones came in a swarm.

Rahman could not advance or return to the bunker. A Russian soldier guiding them said land mines were everywhere.

He was stuck, and the Russian commander fled.

Rahman eventually suffered a leg wound that sent him to a hospital near Moscow. He escaped from the medical center and went directly to the Bangladeshi embassy in Moscow, which prepared a travel pass for him to leave the country.

Some months later, Rahman helped his brother-in-law Jehangir Alam, who also spoke with AP, run away using the same method — leaving the hospital after being wounded and appealing to the embassy.

Families in Lakshmipur hold tightly to the documents of their missing loved ones, believing that one day, when presented to the right person, the papers might unlock the path to their return.

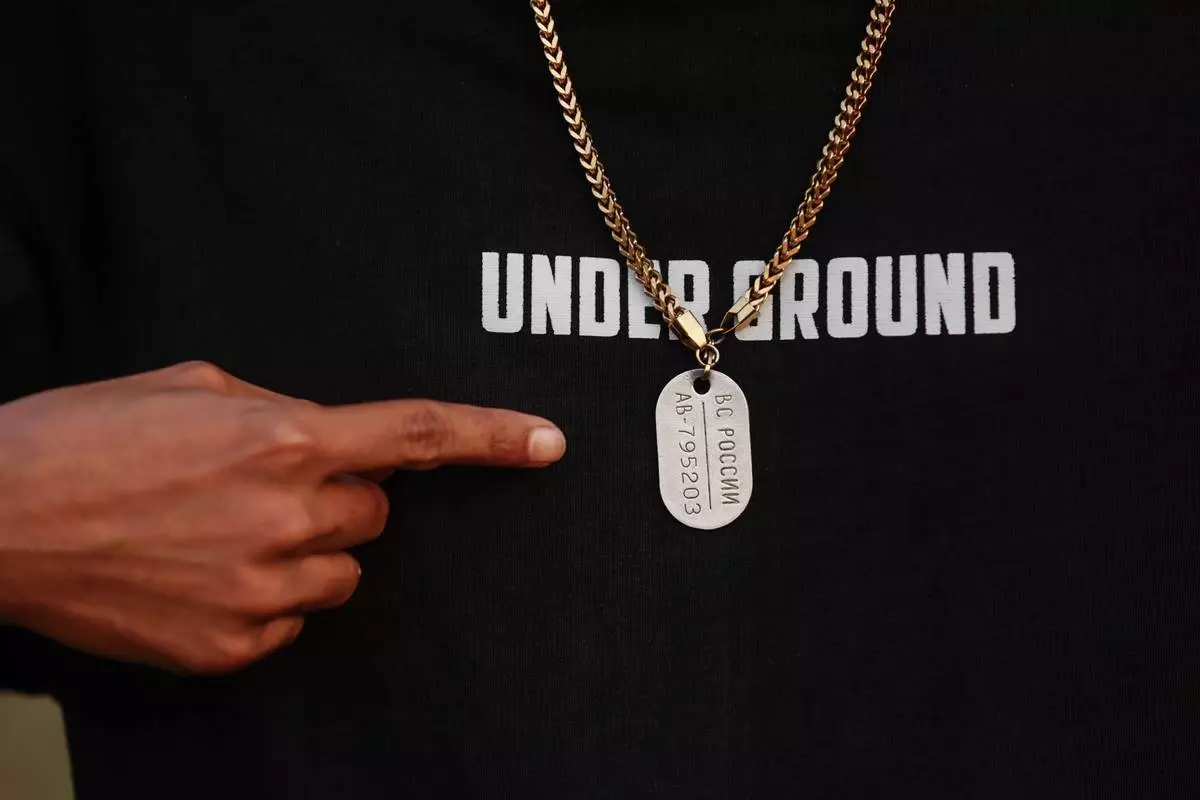

The documents included photos of Russian business visas, military contracts and army dog tags. The papers were sent by the missing men, who urged relatives to complain to recruiting agents.

The contracts were verified by two Russian groups helping men evade or get out of military service. Maj. Vladimir Yaltsev, head of the Kostroma regional recruitment center for contract military service, is listed as signing the contracts on behalf of the Russian military.

In their final messages, these husbands, sons and fathers conveyed to relatives that they were being forcibly taken to the front lines in Ukraine. After that, all communication ceased.

The families filed a complaint with police in Dhaka and traveled on three occasions to the capital to pressure the government to investigate.

Salma Akdar has not heard from her husband since March 26. In their last conversation, Ajgar Hussein, 40, told her he had been sold to the Russian army. The couple has two sons, ages 7 and 11.

Hussein left in mid-December 2024, believing he was being offered a job as a laundry attendant in Russia, his wife said. He had recently returned from Saudi Arabia and planned to stop working overseas for a spell, she explained. But believing Russia offered opportunities to make money, he left again. He sold some of his land to pay the agent's fees.

For two weeks, he was in regular touch. Then he told his wife he was being taken to an army camp where they were trained to use weapons and carry heavy loads up to 80 kilograms (176 pounds). “Seeing all this, he cried a lot and told them, ‘We cannot do these things. We have never done this before,'” his wife said.

For two months after that, he was offline. He reappeared briefly to explain they were being forced to fight in the war.

Russian commanders "told him that if he did not go, they would detain him, shoot him, stop providing food,” she said.

Families in the village confronted the recruiting agent, demanding to know why their loved ones were being trained for war. The agent replied dismissively, saying that it was standard procedure in Russia, insisting that even launderers had to undergo similar training.

Hussein left a final audio note for this wife: “Please pray for me."

Mohammed Siraj’s 20-year-old son, Sajjad, departed believing he would be working as a chef in Russia. He needed to support his unemployed father and chronically ill mother.

Siraj wept as he described his son begging him to ask the agent why he was being made to undergo military training. Sajjad fought with his Russian commanders, insisting he had come to be a chef, not to fight. They threatened him with jail if he did not comply. Then someone else threatened to shoot him, his father recalled.

Sajjad called the family and said he was being taken to battle. “That is the last message from my son,” he said.

In February, Siraj learned through a Bangladeshi man serving with Sajjad that his son had been killed in a drone attack. Unable to bear telling his wife the truth, Siraj assured her that their son was doing well. But word spread through the village.

“You lied to me,” Siraj recalled her saying as she confronted him. Soon after, she died, calling out for her son in her final moments.

In late 2024, families approached BRAC, an organization that advocates for Bangladeshi workers, and said they could no longer reach their relatives in Russia. That prompted the organization to investigate. It uncovered at least 10 Bangladeshi men who are still missing after they were were lured to fight.

“There are two or three layers of people who are profiting,” said Shariful Islam, the head of BRAC's migration program.

Bangladesh police investigators uncovered a trafficking ring in Russia after a Bangladeshi man returned in January 2025, alleging he had been deceived into fighting. The police believe that similar networks, operated by Bangladeshi intermediaries with connections to the Russian government, are responsible for facilitating the entry of Bangladeshis into Russia.

Another nine people were discovered to have been lured into fighting based on that police investigation, according to investigator Mostafizur Rahman. The Associated Press reviewed the police report filed by one victim's wife, who said he went to Russia expecting to work in a chocolate factory. A middleman, a Bangladeshi with Russian citizenship who was residing in Moscow, has been charged.

It's not clear how many Bangladeshis were lured to Russia. A Bangladeshi police investigator told AP that about 40 Bangladeshis may have lost their lives in the war.

Some go willingly, knowing they will end up on the front lines because the money is too good, according to Rahman, the investigator.

In Lakshmipur, investigators learned that the local agent has been funneling recruits to a central agent associated with a company called SP Global. The company did not respond to AP’s calls and emails. Investigators found it ceased operations in 2025.

Families of the missing individuals said they have not received any money earned by their loved ones. Miajee too said he was never paid.

“I don’t want money or anything else,” Akdar said. “I just want my my children’s father back.”

Associated Press writer Julhas Alam in Dhaka, Bangladesh, contributed to this report.

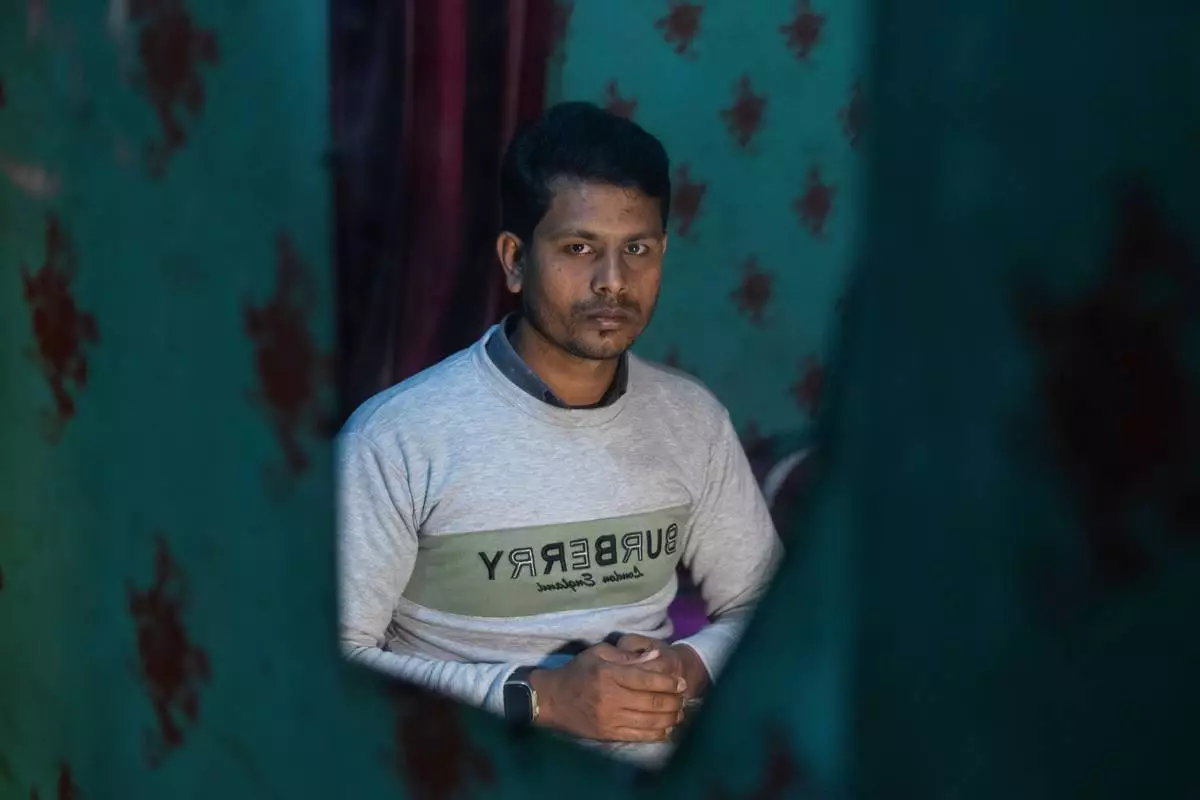

Mohan Miajee, 29, who escaped after fighting for the Russian army, poses for a portrait in Munshiganj, Bangladesh, Dec. 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Rajib Dhar)

Salma Akdar, 28, who has not heard from her husband Ajgar Hussein, 40, for months, sits after speaking to the Associated Press, in Lakshmipur, Bangladesh, Dec. 10, 2025. (AP Photo/Rajib Dhar)

Mohan Miajee, 29, who escaped after fighting for the Russian army, shows his Russian military dog tag in Munshiganj, Bangladesh, Dec. 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Rajib Dhar)

Maksudur Rahman, 31, who escaped after fighting for the Russian army, poses during an interview with the Associated Press in Lakshmipur, Bangladesh, Dec. 10, 2025. (AP Photo/Rajib Dhar)

Maksudur Rahman, 31, who escaped after fighting for the Russian army, shows a Russian military dog tag during an interview with The Associated Press in Lakshmipur, Bangladesh, Dec. 10, 2025. (AP Photo/Rajib Dhar)