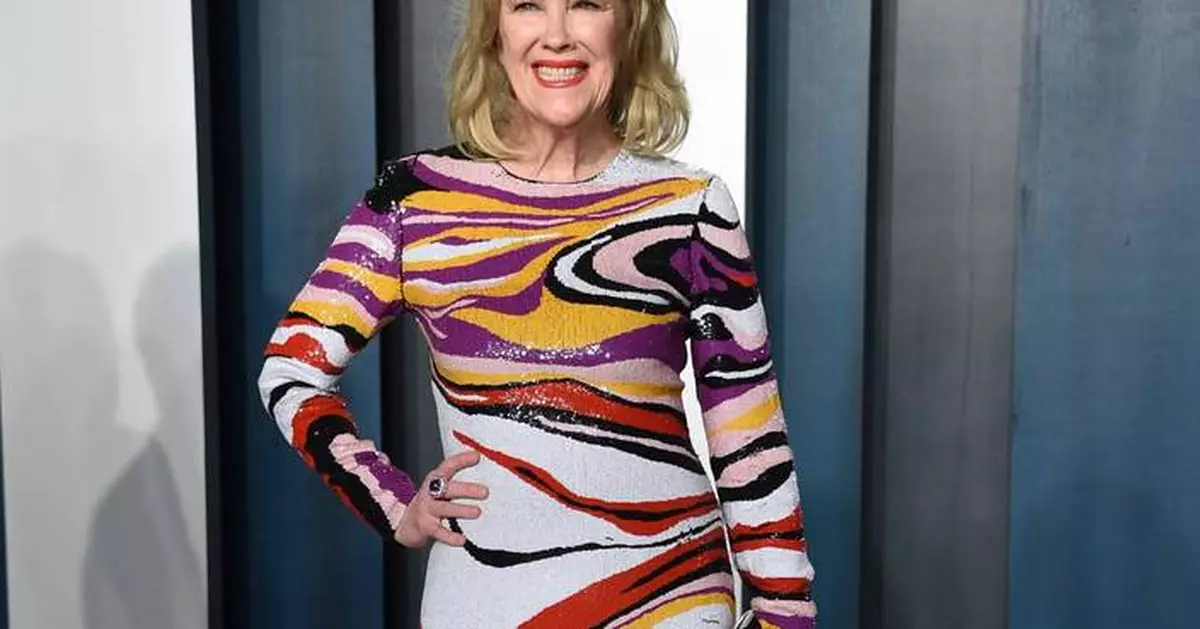

Catherine O’Hara was never afraid to go big. The wild accent as Moira Rose on “Schitt’s Creek.” Delia Deetz’s possessed dance to “Day-O (The Banana Boat Song)” in “Beetlejuice.” The way she screamed “KEVIN!” in two “Home Alones” as Kate McCallister.

But it wasn’t boldness alone that made her one of the greats, and her characters memorable: No matter how absurd or how preposterous or even cliche on the page, there was always a beating heart underneath the silliness, a compassion that shone through. Yes, even as Cookie Fleck, with all her ex-boyfriends, in “Best in Show.”

Kevin Nealon said it simply: “She changed how so many of us understand comedy and humanity.”

Because of that innate grasp on her craft, unwillingness to settle into nostalgia and uncanny ability to invent herself anew with each project, her characters would impact multiple generations of film, television and comedy fans. Before she died at age 71, she was still forging new trails as the ousted studio executive Patty Leigh in “The Studio.” And she did it all with grace and humility, a diva only when the role and costume demanded it.

As fellow Canadian Sarah Polley, who she acted with on “The Studio,” wrote on Instagram Friday: “She was the kindest and the classiest. How could she also have been the funniest person in the world?”

Just eight years younger than another comedy trailblazer Gilda Radner, whom she understudied for at “The Second City” in Toronto, O’Hara was not an obvious candidate for stardom as the second youngest of seven in a decidedly non-showbiz, Catholic family. But she loved comedy, obsessing over “Monty Python” in high school and even trying to meet them at the airport once after hearing they were flying in. And when her brother began dating Radner, she followed that trail to the improv stage.

Her first job was not on stage, however, but as a server where she absorbed all that she could. Though she was turned down after her first audition, she wasn’t deterred; She joined the company in 1974. By 1976 she was an essential part of the cast’s transition to television on “SCTV,” where she did original characters and impersonated well-known personalities of the time, including Meryl Streep, who she’d later act alongside.

“My crutch was, in improvs, when in doubt, play insane,” O’Hara told The New Yorker in 2019. “You didn’t have to excuse anything that came out of your mouth. It didn’t have to make sense.”

By the time the show ended in 1984, she was itching for something more, something deeper and started reading scripts for films. Some equated her pickiness (including pulling out of “Saturday Night Live”) with a kind of lack of ambition. For her, it was about waiting for the right thing. Though her film debut was less than auspicious (in the poorly reviewed Canadian thriller “Double Negative” alongside “SCTV” peers like John Candy and Eugene Levy) she soon found her footing working with the likes of Martin Scorsese in “After Hours” and Mike Nichols in “Heartburn,” where she’d play the gossipy beltway journalist friend of Streep and Jack Nicholson.

“You have to try to make this person a real person,” she said in a 1986 CNN interview. “When I first read it, I thought oh this woman does nothing but gossip. But then I started seeing her as a human being, like myself.”

It’s an impulse that served her well during her Hollywood ascent in the late 1980s and early 1990s. You can watch “Home Alone” for the hijinks, but O’Hara made it emotional and grounded as the mom just trying to get back to her child. There was humor, yes (remember the fake Rolex?) but then, a beat later, there were tears. Even Delia Deetz was relatable, giving her husband a withering glare at his tone-deaf suggestion that she might now be able to make a decent meal in her new suburban prison.

She was feisty in period garb as Wyatt Earp’s sister-in-law, sweetly crazy as the depressed, overwhelmed mother to Colin Hanks in “Orange County,” and crazy-crazy as Marty Funkhouser’s sister Bam Bam in “Curb Your Enthusiasm.”

From her perspective, nothing was as big as “Schitt’s Creek,” an unlikely cultural phenomenon that had everyone suddenly pronouncing baby as “bébé” (and it wasn't because of a sudden French language surge on Duolingo). Few actors get to create their own language and cadence as O’Hara managed to do with Moira Rose.

That unmistakable and unplaceable accent, she told Rolling Stone in 2020, was sort of “in defense of creativity.” She was inspired by women she’d met over the years who, out of insecurity and pride, create new personas whole cloth. As far as the look went, socialite Daphne Guinness was the starting point.

“I think that Canadians have not only a sense of humor about others but about themselves, which I think is the healthiest and best kind of sense of humor to have,” she said in that same Rolling Stone interview. “There’s an edge to it but with a compassion and love.”

Just think about Levy’s Mitch and O’Hara’s Mickey in Christopher Guest’s “A Mighty Wind” singing that mock folk song “A Kiss at the End of the Rainbow” with its saccharine sweet lines. It is ridiculous. It is funny. And it might just make you cry a little too.

FILE - Eugene Levy, from left, Annie Murphy, Daniel Levy and Catherine O'Hara cast members in the series "Schitt's Creek" pose for a portrait during the 2018 Television Critics Association Winter Press Tour in Pasadena, Calif., on Jan. 14, 2018. (Photo by Willy Sanjuan/Invision/AP, File)

FILE - Former cast members of SCTV, from left, Dave Thomas, Joe Flaherty, Catherine O'Hara, Andrea Martin, foreground, Harold Ramis, Eugene Levy and Martin Short, pose at the U.S. Comedy Arts Festival on March 6, 1999, in Aspen, Colo. (AP Photo/E Pablo Kosmicki, File)

FILE - Catherine O'Hara, star of "Schitt's Creek," appears at the Vanity Fair Oscar Party in Beverly Hills, Calif., on Feb. 9, 2020. (Photo by Evan Agostini/Invision/AP, File)

Nine people, including former CNN anchor Don Lemon and another journalist — have been charged with violating two different federal laws in connection with the protest that interrupted a worship service at a Minnesota church earlier this month.

The group that barged into a worship service that Sunday was upset that the head of a local field office for U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement serves as a pastor. The protest was quickly denounced by President Donald Trump, Attorney General Pam Bondi and other officials, as well as many religious leaders.

Lemon and a local reporter were covering the protest on Jan. 18 at the Cities Church in St. Paul. A grand jury in Minnesota indicted Lemon and others on charges of conspiracy and interfering with the First Amendment rights of worshippers. The indictment alleges various actions by the group that entered the church, including what Lemon said as he reported on the event for his livestream show.

The arrests of Lemon and independent journalist Georgia Fort are especially troubling for legal experts and media groups who worry about the chilling effect on coverage of the Trump administration.

David Harris, a University of Pittsburgh law professor specializing in criminal law, said the charges against the protesters are more tenable, given the federal laws against disrupting the free exercise of worship. “A court will have to sort that out,” he said.

But charges against reporters are troubling, he said.

“Charging journalists for being there covering the disruption does not mean they were part of the disruption,” Harris said. “Don Lemon and other journalists are the way that we the public are finding out what is happening in these spaces,” he said. “They are our eyes and ears. The message that is being sent is that journalists like Don Lemon and others should feel intimidated from doing this.”

The two key laws cited in the complaints against those who were arrested were passed more than a century apart — one rooted in efforts to prevent intimidation by the post-Civil War Ku Klux Klan and the other to enable access to abortion clinics, though they both have had wider applications.

Here are some details about those laws:

The Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances law, known as the FACE Act for short, was passed in 1994 to help ensure that patients seeking care at an abortion clinic — as well as the doctors and nurses who work there — could safely access the facilities that often draw protests. It followed incidents of violence targeting clinic workers.

A Republican-sponsored clause that provided for penalties for disruptions of worship services was also incorporated into the law.

Anti-abortion conservatives have denounced the law, focusing on the clinic protections. Trump last year pardoned several people convicted for blockading clinics. His Justice Department scaled back FACE Act prosecutions of those accused of blocking clinics, claiming there had been a “weaponization” of the law.

But the U.S. Supreme Court, despite having overturned the Roe v. Wade decision that had legalized abortion nationwide, last year refused to hear a challenge to the constitutionality of FACE.

In 2025, 42 House Republicans co-sponsored legislation, introduced by Rep. Chip Roy, R-Texas, to repeal the FACE Act. The conservative Heritage Foundation supported the stalled repeal effort, calling the FACE Act “an ideological weapon” designed to suppress anti-abortion activity.

They have contended the worship-protection aspect of the law hasn't been invoked in the past. In 2025, the Justice Department did invoke the act in a lawsuit against demonstrators who protested outside of a synagogue.

Someone charged with their first violation of the FACE Act could be fined or sentenced up to one year in jail. Subsequent offenses, or charges that involve injuries, deaths or damage, could face tougher penalties.

The other charges against Lemon and Fort are based on a law commonly known as the Conspiracy Against Rights law, which was enacted shortly after the Civil War. It was originally designed to target vigilante groups such as the Ku Klux Klan. The law prohibits intimidating or otherwise preventing someone from exercising constitutional rights.

The Klan had been targeting those newly freed from slavery, but over the years the law has been revised to apply to a wide range of violations of constitutional rights. It was used to charge suspects in the “Mississippi Burning” killings of three civil rights workers in 1964. It has been used in cases ranging from church arsons and antisemitic intimidation to political conspiracy and witness tampering.

The law carries a penalty of up to 10 years in prison –- or more if it involves injury, death or destruction of property.

Harris said it's important for Americans to be able to see what's happening so they can make up their own minds, instead of only hearing officials describe what happened.

“We all have had the experience of them telling us things that simply do not square with what we see with our own eyes," he said. “Journalists being present to witness these things and report them are crucial to our being able to make our minds about what our government is doing.”

Jonathan Manes, senior counsel in the MacArthur Justice Center’s Illinois Office, agreed.

“It's astonishing that the federal government is criminally charging journalists for covering a protest,” said Manes, whose work focuses on governmental civil rights violations.

“The crucial point is that a journalist covering activities going on is not part of those activities,” he said. “None of this is to say that the protest here was a good thing or that it was even allowed, but journalists shouldn’t be charged federally with conspiracy when they’re covering it."

AP reporters Tiffany Stanley in Washington and Audrey McAvoy in Honolulu contributed.

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

FILE - Don Lemon attends the 15th annual CNN Heroes All-Star Tribute at the American Museum of Natural History, Sunday, Dec. 12, 2021, in New York. (Photo by Evan Agostini/Invision/AP, File)

Cities Church is seen in St. Paul, Minn. where activists shut down a service claiming the pastor was also working as an ICE agent, Monday, Jan. 19, 2026 in St. Paul, Minn. (AP Photo/Angelina Katsanis)