ANN ARBOR, Mich.--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Feb 10, 2026--

The U.S. economy faces a witches' brew of destructive macro and microeconomic problems: increasing customer switching costs and complaints, with stagnating satisfaction. Paradoxically, customer defections are down — not up. These are not signs of a healthy economy.

This press release features multimedia. View the full release here: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20260210746258/en/

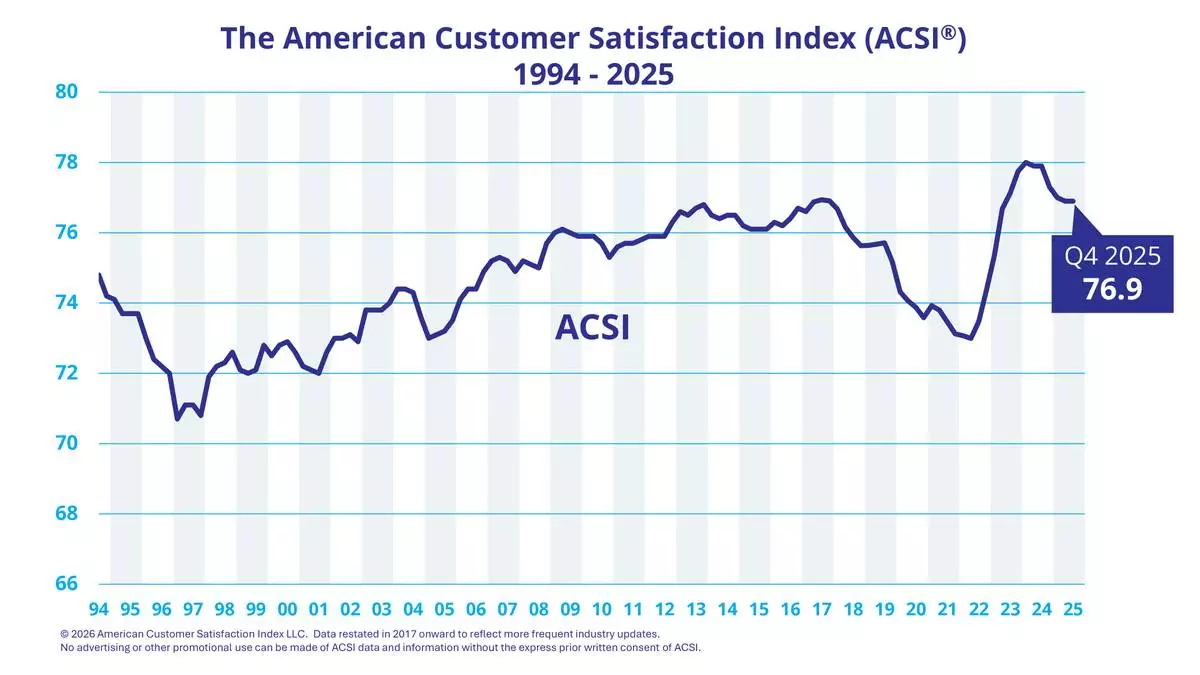

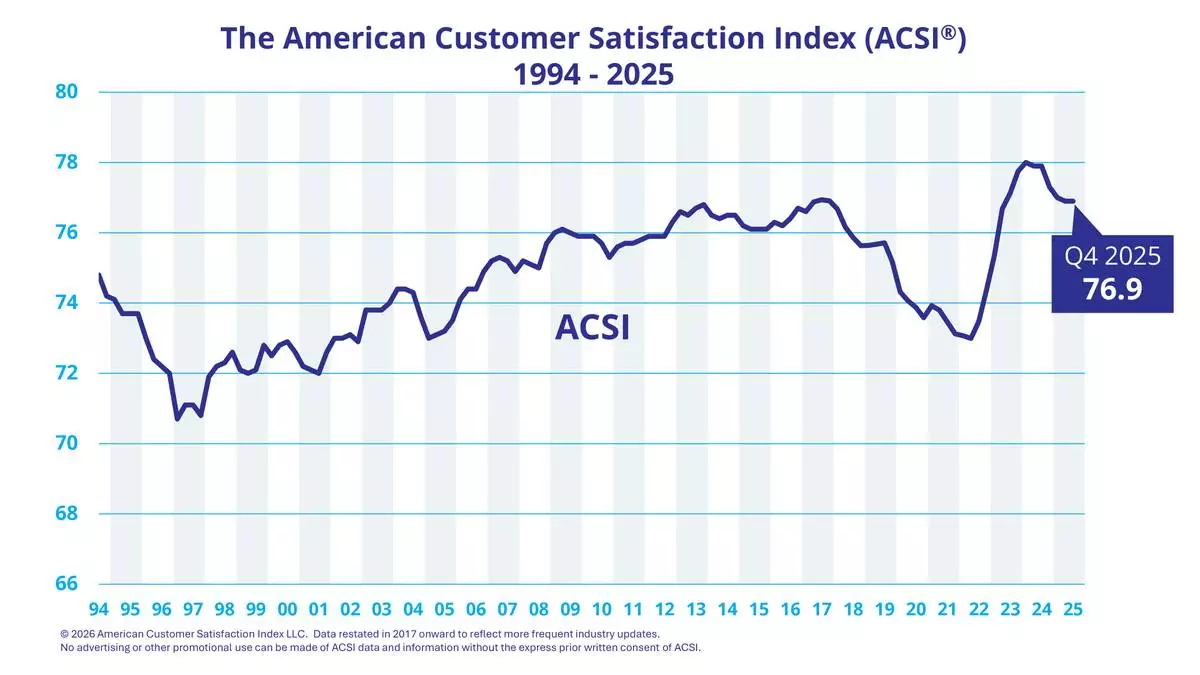

Over the past six months, the American Customer Satisfaction Index (ACSI ® ) has remained unchanged — even at the first decimal. From a sample of about 200,000 customers, the national ACSI score holds at 76.9 (out of 100) for the fourth quarter of 2025. On an annual basis, the Index fell by 0.5% and has not materially increased since 2017.

At the macro level, compounding market concentration, increasing seller pricing power, and higher buyer switching costs are major causes for the lack of improvement. At the micro level, irrelevant performance metrics and data-discordant analytics have made resource allocation for strengthening customer relationships next to impossible.

"In well-functioning markets, buyer satisfaction and seller profits move together," said Claes Fornell, founder of the ACSI and the Distinguished Donald C. Cook Professor (Emeritus) of Business Administration at the University of Michigan. "When seller profits increase without a corresponding rise in buyer utility, it is an indicator of market inefficiency. Decoupling seller profit from buyer satisfaction impedes economic growth and slows innovation. Buyer surplus stagnates and inflation accelerates. Escalating M&A activity, without a corresponding increase in antitrust enforcement, has compounded the problem. Tariffs have had a similar effect by discouraging international competition."

The 1946-1948 World War II aftermath, the 2007-2009 Great Recession, and the COVID-19 pandemic's shock to supply chains provide warnings, some of which apply today. Sellers took advantage of limited competition and raised prices.

During COVID-19, profit margins soared while customer satisfaction fell. The Great Recession of 2007-2009 was similar in some respects — it separated quantity of economic output (GDP) from quality of economic output (ACSI). Subsequently, cumulative GDP growth (post-2007) slowed by 13.5% — about $5 trillion in today's money. Profits began to account for more of national income and increased more than consumer spending did.

As to microeconomic consequences and corporate management concerns, pent-up customer defection is of increasing concern for managers as well as shareholders. It represents the unrealized customer churn that accumulates over time and is preceded by weak or stagnant customer satisfaction, increasing customer complaints, and higher customer switching costs. It is facilitated by contracts, lock-ins, market concentration, subscriptions, a lack of substitutes, and consumer risk aversion.

Pent-up customer defection is a stock of covert risk — it is not a flow — and when released, it moves rapidly. It might be avoided, or its effect may be tamed, if corporations include more financial, accounting, and analytical expertise in building strong customer relationships. Strong customer relationships are important, albeit intangible, financial assets in a competitive marketplace and would benefit if managed as such. History is clear as to what will happen to firms that do not create strong customer relationships based on profit for the seller and satisfaction and utility for the buyer. They tend to occupy the bottom of the ACSI roster.

Strong customer relationships in competitive markets are critical for customer retention. Higher retention, in turn, has compounding multiplicative effects — and at high levels of retention, exponentially increasing effects — on revenue growth and profit, while simultaneously reducing uncertainty and cash flow instability.

Claes Fornell, the Donald C. Cook Distinguished Professor of Business (Emeritus) at the University of Michigan, is the primary author of this press release. He led the development of the American Customer Satisfaction Index with assistance from Eugene W. Anderson, University of Pittsburgh; Michael D. Johnson, Cornell University; Birger Wernerfelt, M.I.T.; and David F. Larcker, Stanford University.

According to Google Scholar, Professor Fornell is the most cited person in the world on customer satisfaction and one of the most cited econometricians/statisticians with respect to structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. He holds honorary doctorates from several universities.

For more, follow the American Customer Satisfaction Index on LinkedIn and X at @theACSI or visit www.theacsi.org.

No advertising or other promotional use can be made of the data and information in this release without the express prior written consent of ACSI LLC.

About the ACSI

The American Customer Satisfaction Index (ACSI ® ) is a national economic indicator and a leading provider of customer analytics products that help organizations build lasting customer relationships and prove ROI on experience investments. ACSI's AI-enhanced platform delivers intuitive dashboards and cause-and-effect analytics that pinpoint the quality drivers most predictive of customer allegiance, retention, price tolerance, and financial performance. ACSI data has been shown to correlate strongly with key micro and macroeconomic indicators, including consumer spending, GDP growth, earnings, and stock returns.

Founded in 1994 at the University of Michigan's Ross School of Business, the ACSI measures customer satisfaction with more than 400 companies in over 40 industries, including federal government services, based on approximately 200,000 annual interviews. Learn more at https://www.theacsi.org.

ACSI and its logo are Registered Marks of American Customer Satisfaction Index LLC.

ACSI 1994-2025

TULKAREM, West Bank (AP) — Hanadi Abu Zant hasn’t been able to pay rent on her apartment in the occupied West Bank for nearly a year after losing her permit to work inside Israel. When her landlord calls the police on her, she hides in a mosque.

“My biggest fear is being kicked out of my home. Where will we sleep, on the street?” she said, wiping tears from her cheeks.

She is among some 100,000 Palestinians whose work permits were revoked after Hamas’ Oct. 7, 2023, attack ignited the war in the Gaza Strip. Confined to the occupied territory, where jobs are scarce and wages far lower, they face dwindling and dangerous options as the economic crisis deepens.

Some have sold their belongings or gone into debt as they try to pay for food, electricity and school expenses for their children. Others have paid steep fees for black-market permits or tried to sneak into Israel, risking arrest or worse if they are mistaken for militants.

Israel, which has controlled the West Bank for nearly six decades, says it is under no obligation to allow Palestinians to enter for work and makes such decisions based on security considerations. Thousands of Palestinians are still allowed to work in scores of Jewish settlements across the West Bank, built on land they want for a future state.

The World Bank has warned that the West Bank economy is at risk of collapse because of Israel’s restrictions. By the end of last year, unemployment had surged to nearly 30% compared with around 12% before the war, according to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics.

Before the war, tens of thousands of Palestinians worked inside Israel, mainly in construction and service jobs. Wages can be more than double those in the landlocked West Bank, where decades of Israeli checkpoints, land seizures and other restrictions have weighed heavily on the economy. Palestinians also blame the Palestinian Authority, which exercises limited self-rule in parts of the territory, for not doing enough to create jobs.

About 115,000 Palestinians had work permits that were revoked after the outbreak of the war. Israel initially reinstated around 8,000 according to a report last year from Gisha, an Israeli group advocating for Palestinian freedom of movement. An Israeli official, speaking on condition of anonymity in accordance with regulations, provided a similar figure for reinstated permits last month.

Wages earned in Israel injected some $4 billion into the Palestinian economy in 2022, according to the Institute for National Security Studies, an Israeli think tank. That’s equivalent to about two-thirds of the Palestinian Authority's budget that year.

An Israeli official said Palestinians do not have an inherent right to enter Israel, and that permits are subject to security considerations. The official spoke on condition of anonymity in line with regulations.

Israel seized the West Bank, Gaza and east Jerusalem in the 1967 Mideast war, territories the Palestinians want for a future state. Some 3 million Palestinians live in the West Bank, along with over 500,000 Israeli settlers who can come and go freely.

The war in Gaza has brought a spike in Palestinian attacks on Israelis as well as settler violence. Military operations that Israel says are aimed at dismantling militant groups have caused heavy damage in the West Bank and displaced tens of thousands of Palestinians.

After her husband left her five years ago, Abu Zant secured a job at a food-packing plant in Israel that paid around $1,400 a month, enough to support her four children. When the war erupted, she thought the ban would only last a few months. She baked pastries for friends to scrape by.

Hasan Joma, who ran a business in Tulkarem before the war helping people find work in Israel, said Palestinian brokers are charging more than triple the price for a permit.

While there are no definite figures, tens of thousands of Palestinians are believed to be working illegally in Israel, according to Esteban Klor, professor of economics at Israel's Hebrew University and a senior researcher at the INSS. Some risk their lives trying to cross Israel’s separation barrier, which consists of 9-meter high (30-foot) concrete walls, fences and closed military roads.

Shuhrat Barghouthi’s husband has spent five months in prison for trying to climb the barrier to enter Israel for work, she said. Before the war, the couple worked in Israel earning a combined $5,700 a month. Now they are both unemployed and around $14,000 in debt.

“Come and see my refrigerator, it’s empty, there’s nothing to feed my children,” she said. She can’t afford to heat her apartment, where she hasn’t paid rent in two years. She says her children are often sick and frequently go to bed hungry.

Sometimes she returns home to see her belongings strewn in the street by the landlord, who has been trying to evict them.

Of the roughly 48,000 Palestinians who worked in Israeli settlements before the war, more than 65% have kept their permits, according to Gisha. The Palestinians and most of the international community view the settlements, which have rapidly expanded in recent years, as illegal.

Israeli officials did not respond to questions about why more Palestinians are permitted to work in the settlements.

Palestinians employed in the settlements, speaking on condition of anonymity for fear of retribution, say their employers have beefed up security since the start of the war and are far more willing to fire anyone stepping out of line, knowing there are plenty more desperate for work.

Two Palestinians working in the Mishor Adumim settlement said security guards look through workers’ phones and revoke their permits arbitrarily.

Israelis have turned to foreign workers to fill jobs held by Palestinians, but some say it’s a poor substitute because they cost more and do not know the language. Palestinians speak Arabic, but those who work in Israel are often fluent in Hebrew.

Raphael Dadush, an Israeli developer, said the permit crackdown has resulted in costly delays.

Before the war, Palestinians made up more than half his workforce. He’s tried to replace them with Chinese workers but says it’s not exactly the same. He understands the government’s decision, but says it’s time to find a way for Palestinians to return that ensures Israel’s security.

Assaf Adiv, the executive director of MAAN Workers Association, an Israeli group advocating for Palestinian labor rights, says there has to be some economic integration or there will be “chaos.”

“The alternative to work in Israel is starvation and desperation,” he said.

An Israeli checkpoint between Israel and the West Bank near the West Bank village of Nilin, Monday, Jan. 19, 2026. (AP Photo/Nasser Nasser)

Palestinian public transportation drivers play cards while they wait for passengers at the main bus station, in the West Bank city of Tulkarem Sunday, Jan. 18, 2026. (AP Photo/Nasser Nasser)

Palestinian laborer Shuhrat Barghouthi shows her empty fridge, saying that she struggles to buy food after Israel revoked work permits for Palestinians in the West Bank city of Tulkarem Sunday, Jan. 18, 2026. (AP Photo/Nasser Nasser)

A Palestinian street vendor displays fruits and vegetables for sale in the West Bank city of Tulkarem Sunday, Jan. 18, 2026. (AP Photo/Nasser Nasser)

A Palestinian laborer who works inside a West Bank Israeli industrial zone maintains the garden at his house, in the West Bank city of Jericho, Saturday, Jan. 3, 2026. (AP Photo/Nasser Nasser)