As hundreds of federal and local agents scoured the Arizona desert and chased down potential leads in the nearly two weeks since Nancy Guthrie disappeared from her affluent neighborhood, families of other missing people are reminded how elusive answers can be.

On the one hand, families who spoke to The Associated Press share in the deep pain that Nancy Guthrie's children, including the well-known “Today” show host Savannah Guthrie, have expressed publicly.

Click to Gallery

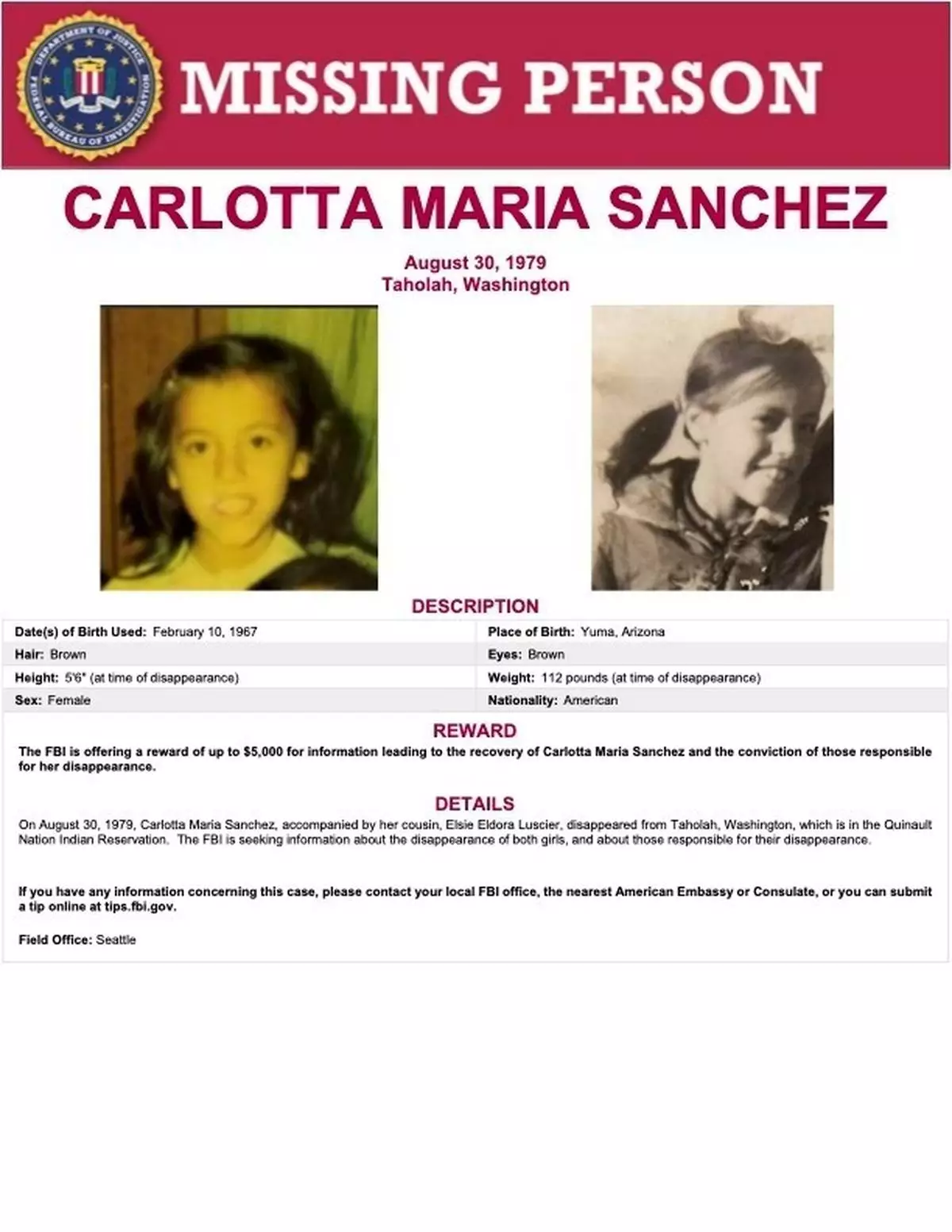

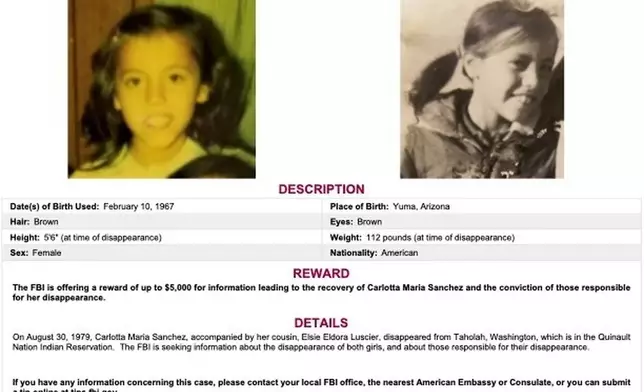

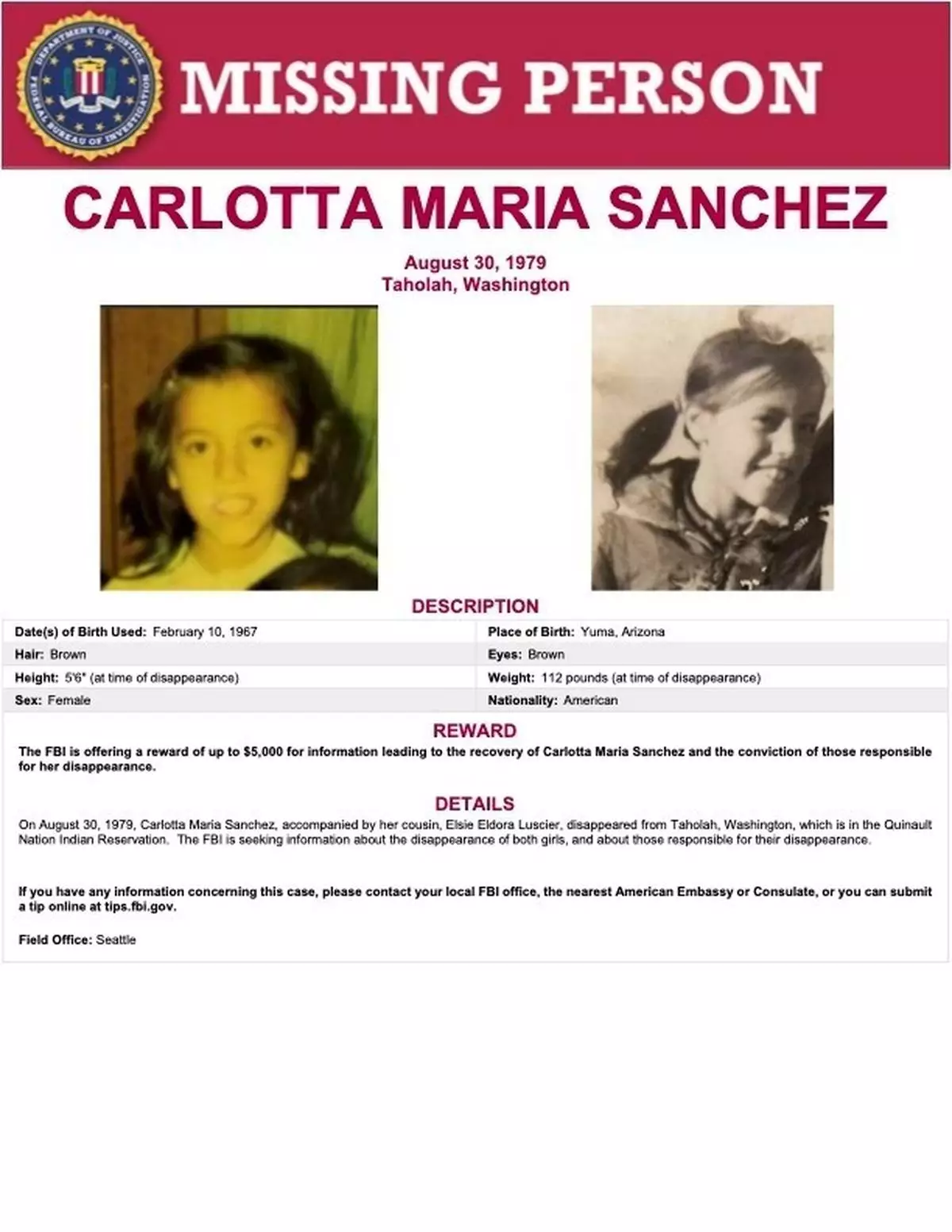

In this undated image released by the Federal Bureau of Investigations shows missing Carlotta Maria Sanchez. (FBI via AP)

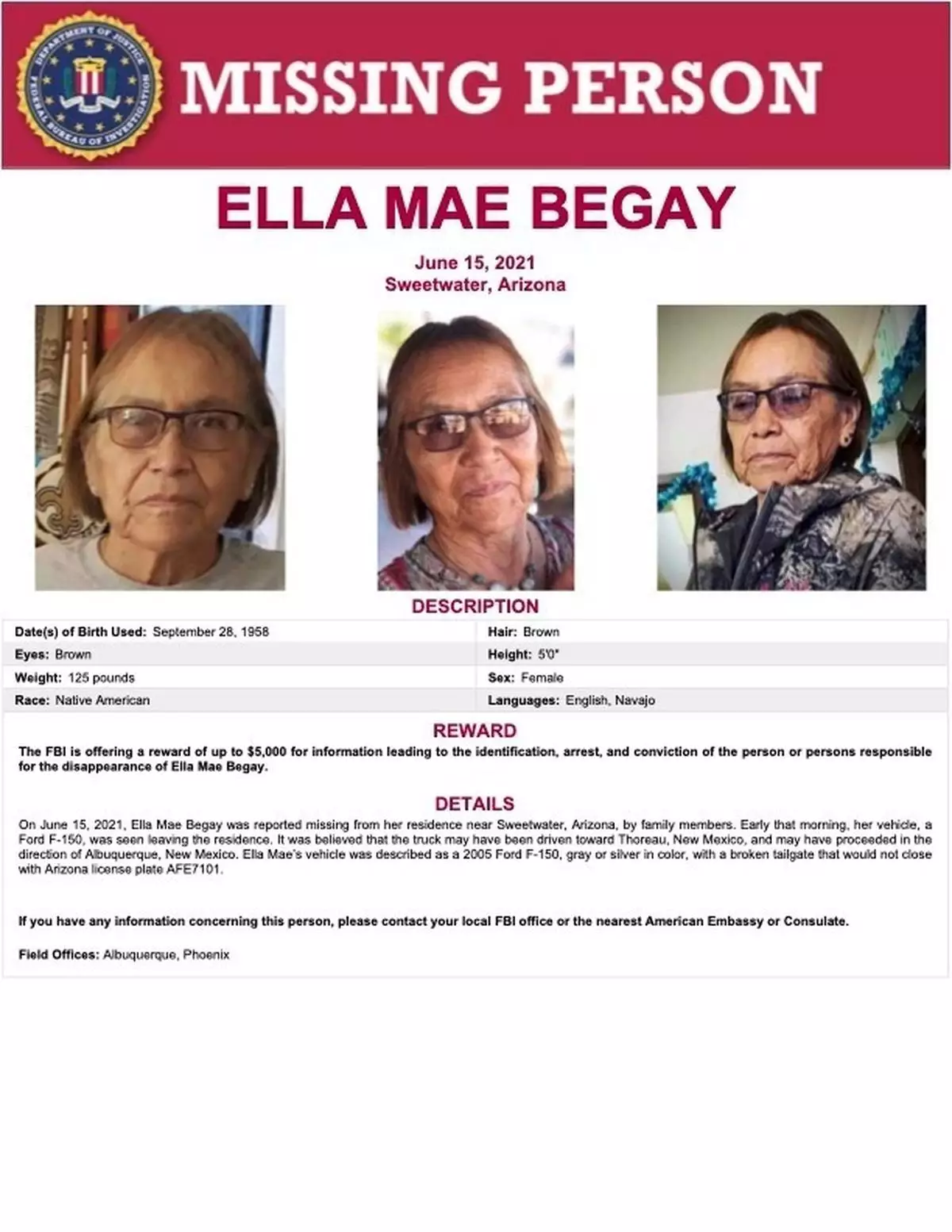

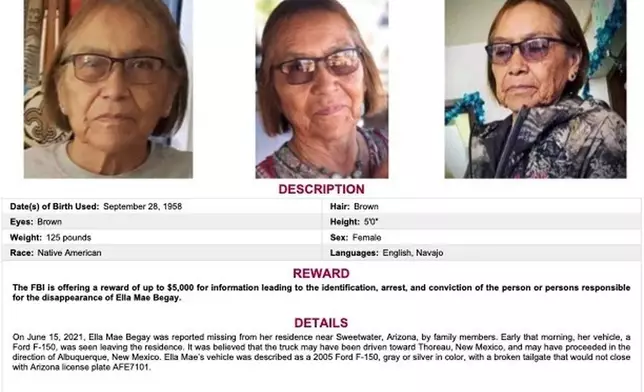

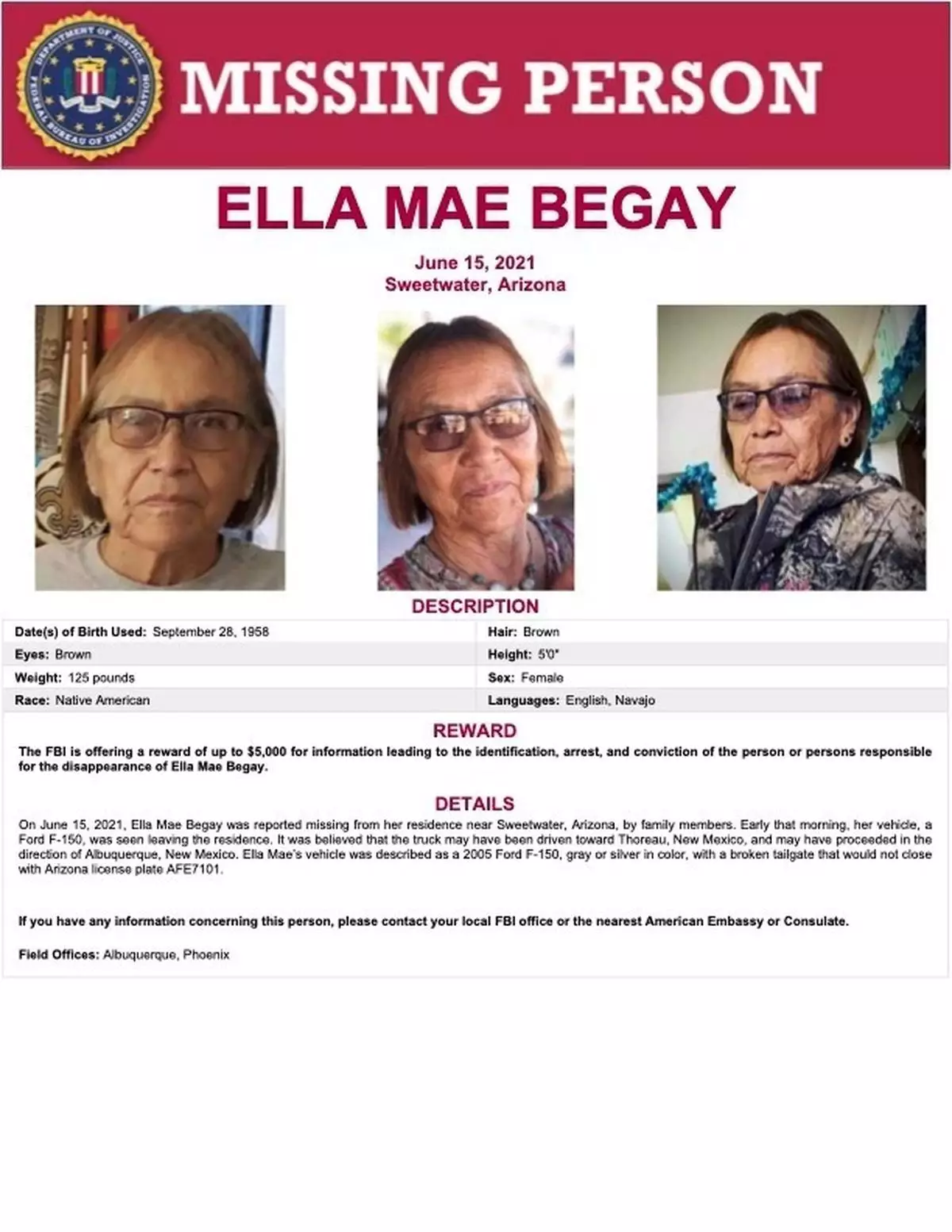

In this undated image released by the Federal Bureau of Investigations shows missing Ella Mae Begay. (FBI via AP)

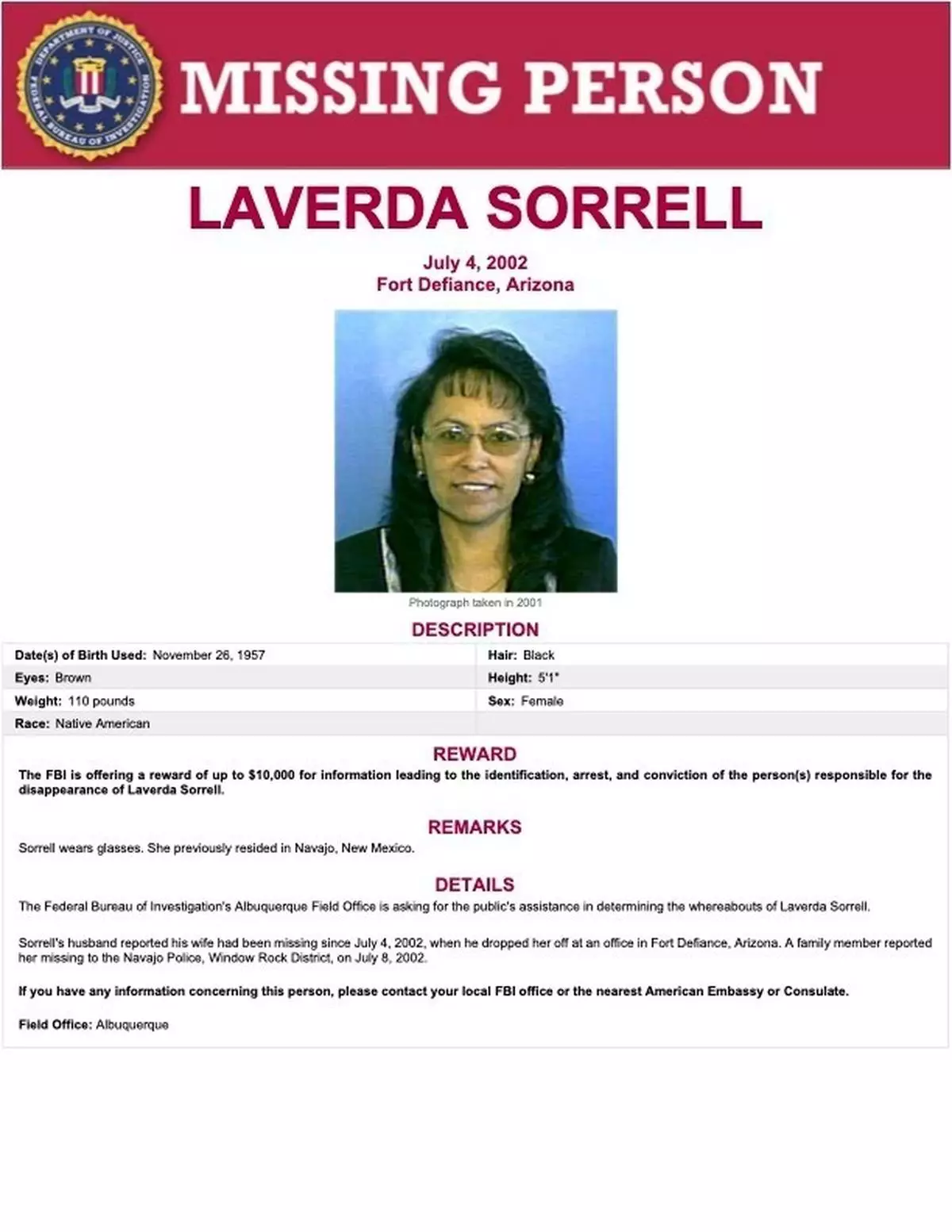

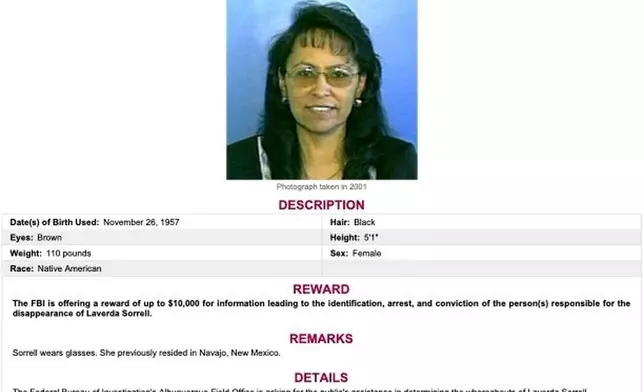

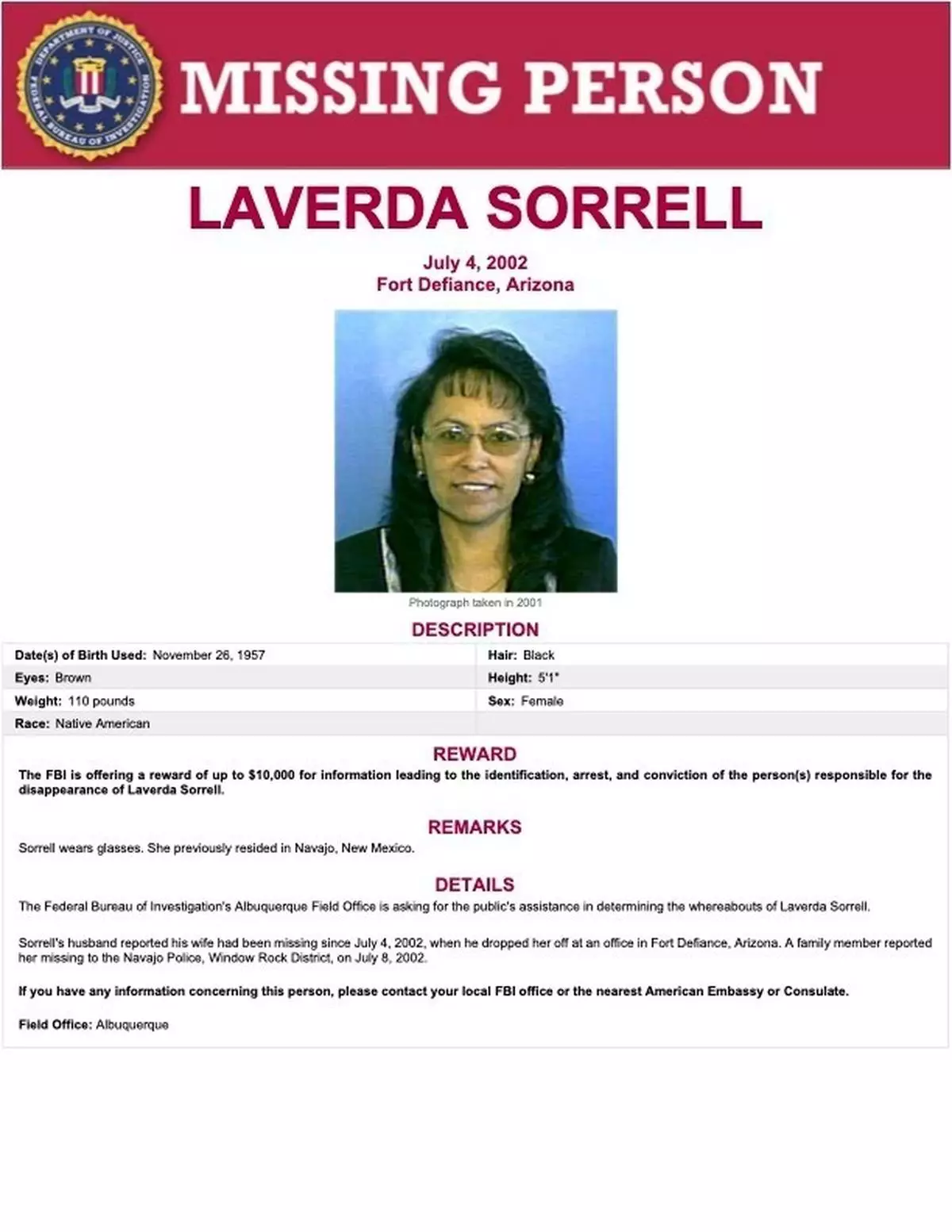

In this undated image released by the Federal Bureau of Investigations shows missing Laverda Sorrell. (FBI via AP)

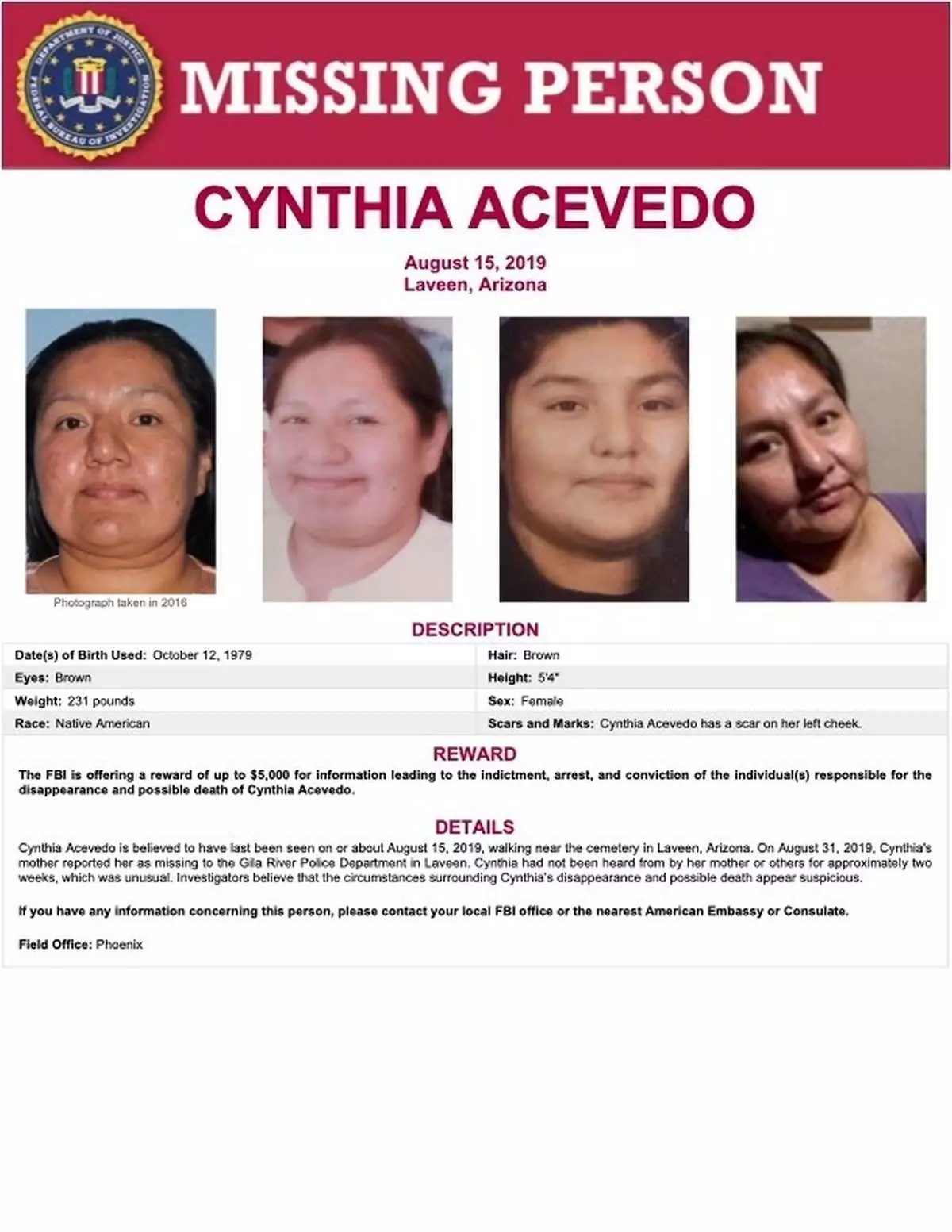

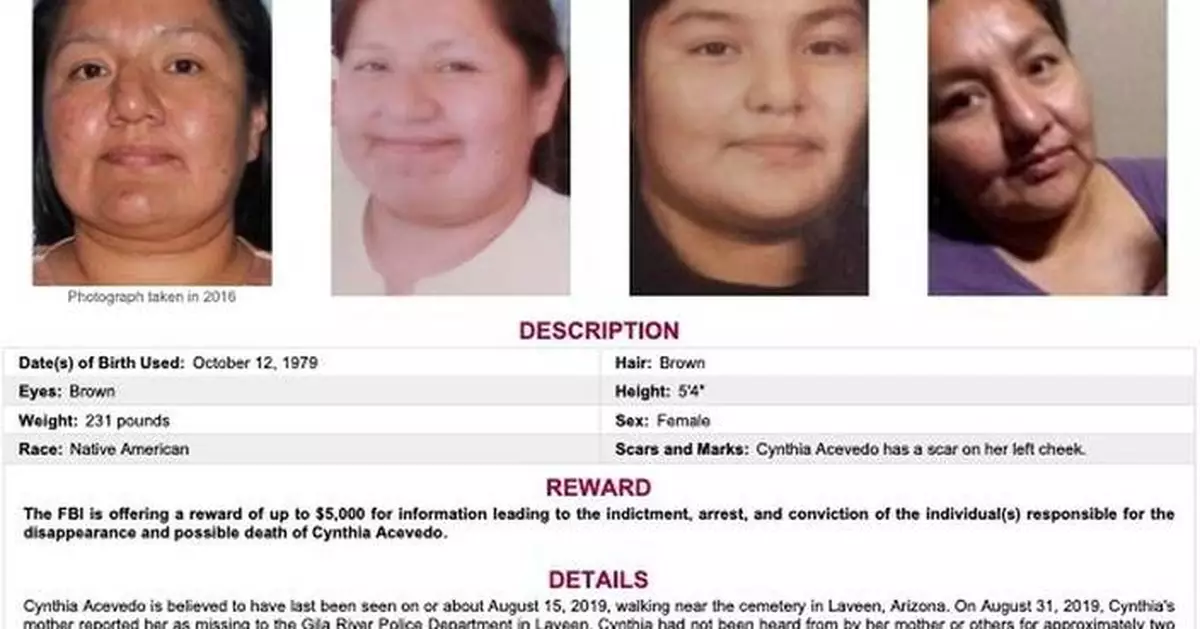

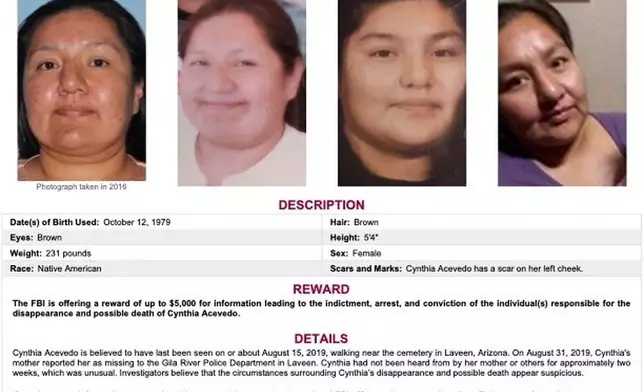

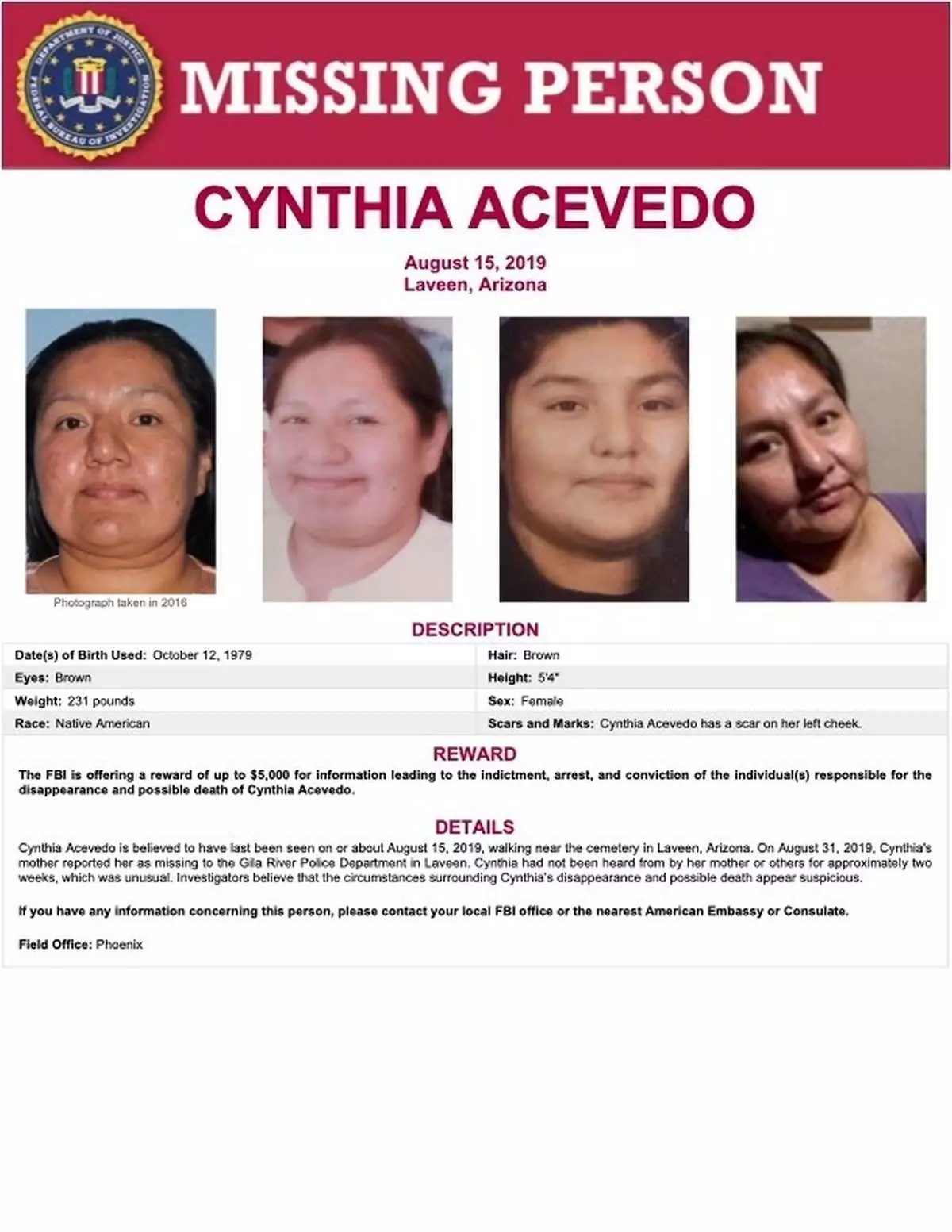

In this undated image released by the Federal Bureau of Investigations shows missing Cynthia Acevedo. (FBI via AP)

On the other, people like Tonya Miller — whose own mother disappeared under suspicious circumstances in Missouri in 2019 — say they feel frustrated as they watch seemingly endless resources flood into the search for Guthrie.

“Families like ours that have just your normal missing people, they have to fight to get any help,” Miller, 44, said.

Miller's mother, Betty Miller, is one of the thousands of people who are listed as abducted each year, according to federal statistics. In most cases, families like Tonya Miller's say it's a full-time job advocating for a fair and thorough investigation.

The country has been engrossed by the apparent kidnapping of Nancy Guthrie, after authorities said they believe she was taken against her will. People in her neighborhood have tied yellow ribbons to tree to express their support.

Multiple news outlets have reported receiving ransom notes, and the Guthrie family has expressed a willingness to pay — although it’s not known whether ransom notes demanding money with deadlines that have already passed were authentic.

In the meantime, several hundred detectives and agents are now assigned to Nancy Guthrie's investigation, the Pima County Sheriff’s Department said.

FBI spokesperson Connor Hagan declined to say how many of those agents were federal law enforcement, and how many were already assigned in Arizona. He also didn't clarify how the federal agency prioritizes different missing persons cases.

However, he said agents from the Critical Incident Response Group, technical experts and intelligence analysts are working to bring Guthrie home. There is also a 24-hour command post where dozens of agents parse through the 13,000 tips that have flooded in from the public, among other responsibilities, according to a post the agency made.

The vast majority of people who are reported missing are believed to be runaways — not kidnapped or abducted.

Throughout all of 2024, the latest year that National Crime Information Center published the data, over 530,000 missing person records were entered. By the end of the year, just over 90,000 cases remained unresolved on that list — some going back decades.

Roughly 95% of the hundreds of thousands of cases filed in 2024 were believed to be runaways and only 1% were listed as abducted.

Often, the abductor is a parent who doesn't have legal guardianship over a child, the report said. It's even more rare for someone to be abducted by a stranger.

The FBI names five kidnapped or missing people, including Nancy Guthrie, from Arizona on its online database of 125 missing or kidnapped people. All five from Arizona are listed as Native American or otherwise disappeared from tribal communities, except for Guthrie.

That racial trend holds true for the rest of the country, too.

A disproportionate number of Black and Indigenous people were among the abducted in 2024, according to the National Crime Information Center report. Roughly a third of the 533,936 missing people listed as abducted in 2024 were Black, even though the U.S. Census reports only 13% of the U.S. population as Black. Similarly, almost 3% of the missing people listed as abducted were Indigenous, compared to the 1.4% of people who are Indigenous in the U.S. writ large.

“Every person deserves to be safe, and when someone is missing, there should be an immediate, coordinated, and effective response," Lucy Simpson, the chief executive officer for the National Indigenous Women’s Resource Center said. “For many Native women, longstanding gaps in resources, coordination, and systemic support for Tribal Nations have made prevention and response more difficult.”

Experts have said that sometimes the attention on high-profile cases can be a major obstacle to law enforcement operations. But Savannah Guthrie's celebrity status has also garnered extensive resources from the federal and local government — including a $100,000 FBI reward for accurate information about her whereabouts or that could lead to an arrest and conviction of whoever took her.

That's in stark contrast, Miller said, to the dearth of help she's received in Sullivan, Missouri, where she's had to use her own time and money to search for her mom, who was last seen in her apartment in the roughly 7,000 person town. A box of Betty Miller’s prescribed fentanyl patches were missing from the apartment and her prescription eye glasses were left on an armchair, Tonya Miller said. There was a massive scratch on her mom's front door that wasn't there before.

The Sullivan Police Department didn't respond to an emailed request for comment Friday.

Despite those suspicious circumstances, local police didn’t treat her mother’s apartment like a crime scene, Tonya Miller said. She had to beg them to take fingerprints and often had to prod them to follow up on tips filed by the public. In the weeks that followed, Tonya Miller organized search parties, printed out fliers and held fundraisers to scrape together a $20,000 reward for her mother.

Tonya Miller said it has become harder as the years go by to know how to help find her mom. She's written letters to elected officials at all levels of government, including President Donald Trump.

“I feel so helpless,” Miller said, “because you just don’t know what to do anymore.”

Riddle is a corps member for The Associated Press/Report for America Statehouse News Initiative. Report for America is a nonprofit national service program that places journalists in local newsrooms to report on undercovered issues.

In this undated image released by the Federal Bureau of Investigations shows missing Carlotta Maria Sanchez. (FBI via AP)

In this undated image released by the Federal Bureau of Investigations shows missing Ella Mae Begay. (FBI via AP)

In this undated image released by the Federal Bureau of Investigations shows missing Laverda Sorrell. (FBI via AP)

In this undated image released by the Federal Bureau of Investigations shows missing Cynthia Acevedo. (FBI via AP)

CAIRO (AP) — The Iranian security agents came at 2 a.m., pulling up in a half-dozen cars outside the home of the Nakhii family. They woke up the sleeping sisters, Nyusha and Mona, and forced them to give the passwords for their phones. Then they took the two away.

The women were accused of participating in the nationwide protests that shook Iran a week earlier, a friend of the pair told The Associated Press, speaking on condition of anonymity for her security as she described the Jan. 16 arrests.

Such arrests have been happening for weeks following the government crackdown last month that crushed the protests calling for the end of the country’s theocratic rule. Reports of raids on homes and workplaces have come from major cities and rural towns alike, revealing a dragnet that has touched large swaths of Iranian society. University students, doctors, lawyers, teachers, actors, business owners, athletes and filmmakers have been swept up, as well as reformist figures close to President Masoud Pezeshkian.

They are often held incommunicado for days or weeks and prevented from contacting family members or lawyers, according to activists monitoring the arrests. That has left desperate relatives searching for their loved ones.

The U.S.-based Human Rights Activists News Agency has put the number of arrests at more than 50,000. The AP has been unable to verify the figure. Tracking the detainees has been difficult since Iranian authorities imposed an internet blackout, and reports leak out only with difficulty.

Other activist groups outside Iran have also been working to document the sweeps.

“Authorities continue to identify people and detain them,” said Shiva Nazarahari, an organizer with one of those groups, the Committee for Monitoring the Status of Detained Protesters.

So far, the committee has verified the names of more than 2,200 people who were arrested, using direct reports from families and a network of contacts on the ground. The arrestees include 107 university students, 82 children as young as 13, as well as 19 lawyers and 106 doctors.

Nazarahari said authorities have been reviewing municipal street cameras, store surveillance cameras and drone footage to track people who participated in the protests to their homes or places of work, where they are arrested.

The protests began in late December, triggered by anger over spiraling prices, and quickly spread across the country. They peaked on Jan. 8 and 9, when hundreds of thousands of people in more than 190 cities and towns across the country took to the streets.

Security forces responded by unleashing unprecedented violence. The Human Rights Activists News Agency has so far counted more than 7,000 dead and says the true number is far higher. Iran’s government offered its only death toll on Jan. 21, saying 3,117 people were killed. The theocracy has undercounted or not reported fatalities from past unrest.

Gholamhossein Mohseni Ejehi, a hard-line cleric who heads Iran’s judiciary, became the face of the crackdown, labeling protesters “terrorists” and calling for fast-tracked punishments.

Since then, “detentions have been very widespread because it’s like a whole suffocation of society,” said one protester, reached by the AP in Gohardasht, a middle-class area outside the Iranian capital. He said two of his relatives and three of his brother’s friends were killed in the first days of the crackdown, as well as several neighbors. The protester spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of being targeted by authorities.

The Nakhii sisters, 25-year-old Nyusha and 37-year-old Mona, were first taken to Tehran’s notorious Evin prison, where they were allowed to contact their parents, their friend said. Later, she said, they were moved to Qarchak, a women’s prison on the outskirts of Tehran where rights groups reported conditions that included overcrowding and lack of hygiene even before the crackdown.

Other people whose arrests were documented by the detainees committee have disappeared into the prisons. The family of Abolfazl Jazbi has not heard from him since his Jan. 15 arrest at a factory in the southern city of Isfahan. Jazbi suffers from a severe blood disorder that requires medication, according to the committee.

Atila Sultanpour, 45, has not been heard from since he was taken from his home in Tehran on Jan. 29 by security agents who beat him severely, according to Dadban, a group of Iranian lawyers based abroad who are also documenting detentions.

Authorities have also moved to suspend bank accounts, block SIM cards and confiscate the property of protesters' relatives or people who publicly express support for them, said Musa Barzin, an attorney with Dadban, citing reports from families.

In past crackdowns on protests, authorities sometimes adhered to a veneer of due process and rule of law, but not this time, Barzin said. Authorities are increasingly denying detainees access to legal counsel and often holding them for days or weeks before allowing any phone calls to family. Lawyers representing arrested protesters also have faced court summons and detention, according to Dadban.

“The following of the law is in the worst situation it has ever been,” Barzin said.

Despite the crackdown, many civic groups continue to issue defiant statements.

The Writers’ Association of Iran, an independent group with a long tradition of dissent, issued a statement describing the protests as an uprising against “47 years of systemic corruption and discrimination.”

It also announced that two of its members had been detained, including a member of its secretariat.

A national council representing schoolteachers urged families to speak out about detained children and students. “Do not fear the threats of security forces. Refer to independent counsel. Make your children’s names public,” it said in a statement.

A spokesman for the council said Sunday that it has documented the deaths of at least 200 minors who were killed in the crackdown. That figure is up several dozen from the count just days before.

“Every day we tell ourselves this is the last list,” Mohammad Habibi wrote on X. “But the next morning, new names arrive again.”

Bar associations and medical groups have also spoken out, including Iran’s state-sanctioned doctors council, which called on authorities to stop harassing medical staff.

Anger over the bloodshed now adds to the bitterness over the economy, which has been hollowed out by decades of sanctions, corruption and mismanagement. The value of the currency has plunged, and inflation has climbed to record levels.

The Iranian government has announced gestures such as launching a new coupon program for essential goods. Labor and trade groups, including a national retirees syndicate, have issued statements condemning the economic and political crisis.

Meanwhile, U.S. President Donald Trump has moved an aircraft carrier and other military assets to the Persian Gulf and suggested the U.S. could attack Iran over the killing of peaceful demonstrators or if Tehran launches mass executions over the protests. A second American aircraft carrier is on its way to the Mideast.

Iran’s theocracy has faced down protests and U.S. threats in the past, and the crackdown showed the iron grip it holds over the country. This week, authorities organized pro-government rallies with hundreds of thousands of people to mark the anniversary of the 1979 Islamic Revolution.

Still, Barzin said, he sees the ferocity of the crackdown as a sign that Iran’s leadership “for the first time is afraid of being overthrown.”

Associated Press writer Kareem Chehayeb in Beirut contributed to this report.

This story corrects ages for Nyusha and Mona.

FILE - In this image from video obtained by the AP outside Iran, a masked demonstrator holds a picture of Iran's Crown Prince Reza Pahlavi during a protest in Tehran, Iran, on Jan. 9, 2026. (UGC via AP, File)

FILE - In this image from video circulating on social media, protesters dance and cheer around a bonfire as they take to the streets of Tehran, Iran, on Jan. 9, 2026. (UGC via AP, File)

FILE - In this image from video made by an individual not employed by The Associated Press and obtained by the AP outside Iran, people block an intersection during a protest in Tehran, Iran, on Jan. 8, 2026. (UGC via AP, File)