GENEVA (AP) — Delegations from Moscow and Kyiv met in Geneva on Tuesday for another round of U.S.-brokered peace talks, a week before the fourth anniversary of Russia’s full-scale invasion of its neighbor.

However, expectations for any breakthroughs in the scheduled two days of talks in Switzerland were low, with neither side apparently ready to budge from its positions on key territorial issues and future security guarantees, despite the United States setting a June deadline for a settlement.

The head of the Ukrainian delegation, Rustem Umerov, posted photos on social media of the three delegations at a horseshoe-shaped table, with the Ukrainian and Russian officials sitting across from each other. U.S. President Donald Trump’s envoy, Steve Witkoff, and son-in-law Jared Kushner sat at the head of the table in front of U.S., Russian, Ukrainian and Swiss flags.

“The agenda includes security and humanitarian issues,” Umerov said, adding that Ukrainians will work “without excessive expectations.”

Discussions on the future of Russian-occupied Ukrainian territory are expected to be particularly tough, according to a person familiar with the talks who spoke to The Associated Press on condition of anonymity because the person was not authorized to talk to reporters.

Russa is still insisting that Ukraine cede control of its eastern Donbas region.

Also in Geneva will be American, Russian and Ukrainian military chiefs, who will discuss how ceasefire monitoring might work after any peace deal, and what's needed to implement it, the person said.

During previous talks in Abu Dhabi, the capital of the United Arab Emirates, military leaders looked at how a demilitarized zone could be arranged and how everyone's militaries could talk to one another, the person added.

Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov cautioned against expecting developments on the first day of talks as they were set to continue on Wednesday. Moscow has provided few details of previous talks.

Ukraine’s short-handed army is locked in a war of attrition with Russia’s bigger forces along the roughly 1,250-kilometer (750-mile) front line. Ukrainian civilians are enduring Russian aerial barrages that repeatedly knock out power and destroy homes.

The future of the almost 20% of Ukrainian land that Russia occupies or still covets is a central question in the talks, as are Kyiv’s demands for postwar security guarantees with a U.S. backstop to deter Moscow from invading again.

Trump described the Geneva meeting as “big talks.”

“Ukraine better come to the table fast,” he told reporters late Monday as he flew back to Washington from his home in Florida.

It wasn’t immediately clear what Trump was referring to in his comment about Ukraine, which has committed to and taken part in negotiations in the hope of ending Russia’s devastating onslaught.

The Russian delegation is headed by Russian President Vladimir Putin’s adviser Vladimir Medinsky, who headed Moscow’s team of negotiators in the first direct peace talks with Ukraine in Istanbul in March 2022 and has forcefully pushed Putin’s war goals. Medinsky has written several history books that claim to expose Western plots against Russia and berate Ukraine.

The commander of the U.S. military — and NATO forces — in Europe, Gen. Alexus Grynkewich, and Secretary of the U.S. Army Dan Driscoll will attend the meeting in Geneva on behalf of the U.S. military and meet with their Russian and Ukrainian counterparts, said Col. Martin O’Donnell, a spokesman for the U.S. commander.

Overnight, Russia used almost 400 long-range drones and 29 missiles of various types to strike 12 regions of Ukraine, injuring nine people, including children, according to the Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy.

Zelenskyy said tens of thousands of residents were left without heating and running water in the southern port city of Odesa. He said Moscow should be “held accountable” for the relentless attacks, which he said undermine the U.S. push for peace.

“The more this evil comes from Russia, the harder it will be for everyone to reach any agreements with them. Partners must understand this. First and foremost, this concerns the United States,” the Ukrainian leader said on social media late Monday.

“We agreed to all realistic proposals from the United States, starting with the proposal for an unconditional and long-term ceasefire,” Zelenskyy noted.

The talks in Geneva took place as U.S. officials also held indirect talks with Iran in the Swiss city.

Meanwhile, Ukraine’s Security Service, or SBU, used long-range drones to strike an oil terminal in southern Russia and a major chemical plant deep inside the country, a Ukrainian security official who spoke on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to speak publicly told the AP.

Drones targeted the Tamanneftegaz oil terminal, one of the biggest ports of its type on the Black Sea, in Russia’s Krasnodar region for the second time this month, starting a fire, the official said.

Drones also hit the Metafrax Chemicals plan, which manufactures chemical components used in explosives and other military materials, in Russia’s Perm region, more than 1,600 kilometers (1,000 miles) from the Ukrainian border, according to the official.

Burrows reported from London. Associated Press writer Illia Novikov in Kyiv, Ukraine, contributed to this report.

Follow AP’s coverage of the war in Ukraine at https://apnews.com/hub/russia-ukraine

In this photo provided by the National Security and Defense Council of Ukraine press office, U.S., center, Ukrainian, right, and Russian delegations attend the next round of trilateral talks on Russia-Ukraine war in Geneva, Switzerland, Tuesday, Feb. 17, 2026. (Ukrainian National Security and Defense Council press office via AP)

In this photo provided by the Ukrainian Emergency Service, firefighters put out the fire in private houses following a Russian air attack in Sumy region, Ukraine, Tuesday, Feb. 17, 2026. (Ukrainian Emergency Service via AP)

In this photo provided by the Ukrainian Emergency Service, a firefighter puts out the fire in private houses following a Russian air attack in Sumy region, Ukraine, Tuesday, Feb. 17, 2026. (Ukrainian Emergency Service via AP)

CHICAGO (AP) — The Rev. Jesse L. Jackson, a protege of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and two-time presidential candidate who led the Civil Rights Movement for decades after the revered leader's assassination, died Tuesday. He was 84.

As a young organizer in Chicago, Jackson was called to meet with King at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee, shortly before King was killed, and he publicly positioned himself thereafter as King's successor.

Santita Jackson confirmed that her father, who had a rare neurological disorder, died at home in Chicago, surrounded by family.

Jackson led a lifetime of crusades in the United States and abroad, advocating for the poor and underrepresented on issues from voting rights and job opportunities to education and health care. He scored diplomatic victories with world leaders, and through his Rainbow/PUSH Coalition, he channeled cries for Black pride and self-determination into corporate boardrooms, pressuring executives to make America a more open and equitable society.

And when he declared, “I am Somebody,” in a poem he often repeated, he sought to reach people of all colors. “I may be poor, but I am Somebody; I may be young; but I am Somebody; I may be on welfare, but I am Somebody,” Jackson intoned.

It was a message he took literally and personally, having risen from obscurity in the segregated South to become America’s best-known civil rights activist since King.

“Our father was a servant leader — not only to our family, but to the oppressed, the voiceless, and the overlooked around the world,” the Jackson family said in a statement posted online. “We shared him with the world, and in return, the world became part of our extended family.”

Fellow civil rights activist the Rev. Al Sharpton said his mentor “was not simply a civil rights leader; he was a movement unto himself.”

“He taught me that protest must have purpose, that faith must have feet, and that justice is not seasonal, it is daily work,” Sharpton wrote in a statement, adding that Jackson taught “trying is as important as triumph. That you do not wait for the dream to come true; you work to make it real.”

Despite profound health challenges in his final years including the disorder that affected his ability to move and speak, Jackson continued protesting against racial injustice into the era of Black Lives Matter. In 2024, he appeared at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago and at a City Council meeting to show support for a resolution backing a ceasefire in the Israel-Hamas war.

“Even if we win,” he told marchers in Minneapolis before the officer whose knee kept George Floyd from breathing was convicted of murder, “it’s relief, not victory. They’re still killing our people. Stop the violence, save the children. Keep hope alive.”

Jackson’s voice, infused with the stirring cadences and powerful insistence of the Black church, demanded attention. On the campaign trail and elsewhere, he used rhyming and slogans such as: "Hope not dope" and "If my mind can conceive it and my heart can believe it, then I can achieve it," to deliver his messages.

Jackson had his share of critics, both within and outside of the Black community. Some considered him a grandstander, too eager to seek out the spotlight. Looking back on his life and legacy, Jackson told The Associated Press in 2011 that he felt blessed to be able to continue the service of other leaders before him and to lay a foundation for those to come.

“A part of our life’s work was to tear down walls and build bridges, and in a half century of work, we’ve basically torn down walls,” Jackson said. “Sometimes when you tear down walls, you’re scarred by falling debris, but your mission is to open up holes so others behind you can run through.”

In his final months, as he received 24-hour care, he lost his ability to speak, communicating with family and visitors by holding their hands and squeezing.

“I get very emotional knowing that these speeches belong to the ages now,” his son, Jesse Jackson Jr., told the AP in October.

Jesse Louis Jackson was born on Oct. 8, 1941, in Greenville, South Carolina, the son of high school student Helen Burns and Noah Louis Robinson, a married man who lived next door. Jackson was later adopted by Charles Henry Jackson, who married his mother.

Jackson was a star quarterback on the football team at Sterling High School in Greenville, and accepted a football scholarship from the University of Illinois. But after he reportedly was told Black people couldn’t play quarterback, he transferred to North Carolina A&T in Greensboro, where he became the first-string quarterback, an honor student in sociology and economics, and student body president.

Arriving on the historically Black campus in 1960 just months after students there launched sit-ins at a whites-only lunch counter, Jackson immersed himself in the blossoming Civil Rights Movement.

By 1965, he joined the voting rights march King led from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama. King dispatched him to Chicago to launch Operation Breadbasket, a Southern Christian Leadership Conference effort to pressure companies to hire Black workers.

Jackson called his time with King “a phenomenal four years of work.”

Jackson was with King on April 4, 1968, when the civil rights leader was slain. Jackson’s account of the assassination was that King died in his arms.

With his flair for the dramatic, Jackson wore a turtleneck he said was soaked with King’s blood for two days, including at a King memorial service held by the Chicago City Council, where he said: “I come here with a heavy heart because on my chest is the stain of blood from Dr. King’s head.”

However, several King aides, including speechwriter Alfred Duckett, questioned whether Jackson could have gotten King’s blood on his clothing. There are no images of Jackson in pictures taken shortly after the assassination.

In 1971, Jackson broke with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to form Operation PUSH, originally named People United to Save Humanity. The organization based on Chicago’s South Side declared a sweeping mission, from diversifying workforces to registering voters in communities of color nationwide. Using lawsuits and threats of boycotts, Jackson pressured top corporations to spend millions and publicly commit to diversifying their workforces.

The constant campaigns often left his wife, Jacqueline Lavinia Brown, the college sweetheart he married in 1963, taking the lead in raising their five children: Santita Jackson, Yusef DuBois Jackson, Jacqueline Lavinia Jackson Jr., and two future members of Congress, U.S. Rep. Jonathan Luther Jackson and Jesse L. Jackson Jr., who resigned in 2012 but is seeking reelection in the 2026 midterms.

The elder Jackson, who was ordained as a Baptist minister in 1968 and earned his Master of Divinity in 2000, also acknowledged fathering a child, Ashley Jackson, with one of his employees at Rainbow/PUSH, Karen L. Stanford. He said he understood what it means to be born out of wedlock and supported her emotionally and financially.

Despite once telling a Black audience he would not run for president “because white people are incapable of appreciating me,” Jackson ran twice and did better than any Black politician had before President Barack Obama, winning 13 primaries and caucuses for the Democratic nomination in 1988, four years after his first failed attempt.

His successes left supporters chanting another Jackson slogan, “Keep Hope Alive.”

“I was able to run for the presidency twice and redefine what was possible; it raised the lid for women and other people of color,” he told the AP. “Part of my job was to sow seeds of the possibilities.”

U.S. Rep. John Lewis said during a 1988 C-SPAN interview that Jackson’s two runs for the Democratic nomination “opened some doors that some minority person will be able to walk through and become president.”

Jackson also pushed for cultural change, joining calls by NAACP members and other movement leaders in the late 1980s to identify Black people in the United States as African Americans.

“To be called African Americans has cultural integrity — it puts us in our proper historical context,” Jackson said at the time. “Every ethnic group in this country has a reference to some base, some historical cultural base. African Americans have hit that level of cultural maturity.”

Jackson’s words sometimes got him in trouble.

In 1984, he apologized for what he thought were private comments to a reporter, calling New York City “Hymietown,” a derogatory reference to its large Jewish population. And in 2008, he made headlines when he complained that Obama was “talking down to Black people” in comments captured by a microphone he didn’t know was on during a break in a television taping.

Still, when Jackson joined the jubilant crowd in Chicago’s Grant Park to greet Obama that election night, he had tears streaming down his face.

“I wish for a moment that Dr. King or (slain civil rights leader) Medgar Evers ... could’ve just been there for 30 seconds to see the fruits of their labor,” he told the AP years later. “I became overwhelmed. It was the joy and the journey.”

Jackson also had influence abroad, meeting world leaders and scoring diplomatic victories, including the release of Navy Lt. Robert Goodman from Syria in 1984, as well as the 1990 release of more than 700 foreign women and children held after Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait. In 1999, he won the freedom of three Americans imprisoned by Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosevic.

In 2000, President Bill Clinton awarded Jackson the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the country’s highest civilian honor.

“Citizens have the right to do something or do nothing,” Jackson said, before heading to Syria. “We choose to do something.”

In 2021, Jackson joined the parents of Ahmaud Arbery inside the Georgia courtroom where three white men were convicted of killing the young Black jogger. In 2022, he hand-delivered a letter to the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Chicago, calling for federal charges against former Chicago Police Officer Jason Van Dyke in the 2014 killing of Black teenager Laquan McDonald.

Jackson, who stepped down as president of Rainbow/PUSH in July 2023, disclosed in 2017 that he had sought treatment for Parkinson’s, but he continued to make public appearances even as the disease made it more difficult for listeners to understand him. Earlier this year doctors confirmed a diagnosis of progressive supranuclear palsy, a life-threatening neurological disorder. He was admitted to a hospital in November for nearly two weeks.

During the coronavirus pandemic, he and his wife survived being hospitalized with COVID-19. Jackson was vaccinated early, urging Black people in particular to get protected, given their higher risks for bad outcomes.

“It’s America’s unfinished business — we’re free, but not equal,” Jackson told the AP. “There’s a reality check that has been brought by the coronavirus, that exposes the weakness and the opportunity.”

Former Associated Press writer Karen Hawkins, who left The Associated Press in 2012, contributed to this report. Associated Press writers Amy Forliti in Minneapolis and Aaron Morrison in New York contributed.

FILE - Former South African President Nelson Mandela, left, walks with the Rev. Jesse Jackson after their meeting in Johannesburg, South Africa, Oct. 26, 2005. (AP Photo/Themba Hadebe, File)

FILE - Rev. Jesse Jackson, left, talks with singer and civil right rights activist Harry Belafonte after a news conference announcing the installation of a Nelson Mandela plaque in Yankee Stadium's Monument Park in New York, April 16, 2014. (AP Photo/Kathy Willens, File)

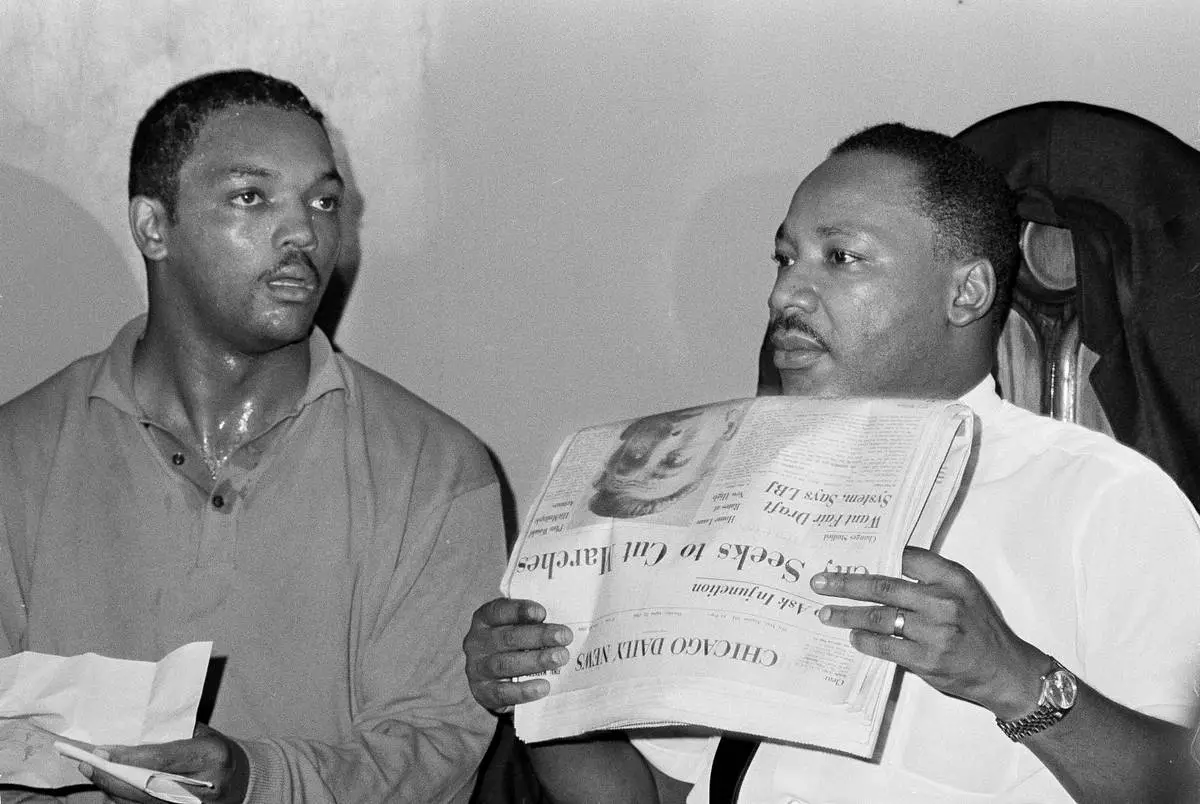

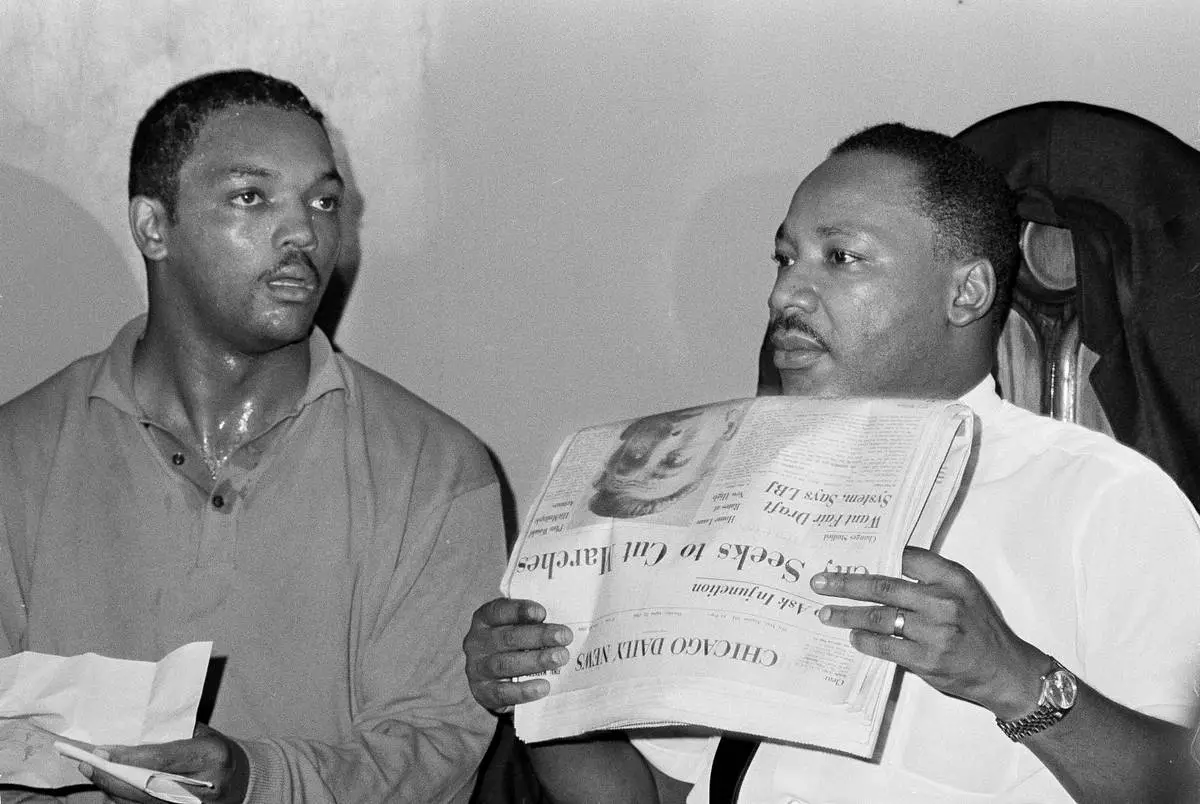

FILE - Civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., right, and his aide Rev. Jesse Jackson are seen in Chicago, Aug. 19, 1966. (AP Photo/Larry Stoddard, File)

FILE - Rev. Jesse Jackson answers questions at a rally, April 19, 2021, in Minneapolis, as the murder trial against the former Minneapolis police Officer Derek Chauvin in the killing of George Floyd advances to jury deliberations. (AP Photo/Morry Gash, File)

FILE - U.S. Rep. Hakeem Jeffries, D-NY, U.S. Rep. Maxine Waters, D-Calif., Rev. Al Sharpton, Rev. Jesse Jackson and NAACP President Derrick Johnson march across the Edmund Pettus bridge during the 60th anniversary of the march to ensure that African Americans could exercise their constitutional right to vote, March 9, 2025, in Selma, Ala. (AP Photo/Mike Stewart, File)

FILE - Democratic presidential hopeful Sen. Barack Obama, D-Ill., left, and the Rev. Jesse Jackson are seen at the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Scholarship Awards Breakfast in Chicago on Jan. 15, 2007. (AP Photo/Charles Rex Arbogast, File)

FILE - Democratic presidential primary candidate Jesse Jackson speaks to a group of his supporters at a rally held at a Baptist Church in Dayton, Ohio, April 14, 1984. (AP Photo/Rob Burns, File)

FILE - Rev. Jesse Jackson gestures to a friend in the balcony at the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Ala., Sept. 15, 2013. The church held a ceremony honoring the memory of the four young girls who were killed by a bomb placed outside the church 50 years ago by members of the Ku Klux Klan. At right is U.S. Rep. Terri Sewell, D-Ala. (AP Photo/Dave Martin, File)

FILE - President George W. Bush speaks with Rev. Jesse Jackson, right, after signing a bill in the Eisenhower Executive Office Building, Dec. 1, 2005, authorizing a statue of civil rights leader Rosa Parks be placed in the U.S. Capitol's Statuary Hall. (AP Photo/Ron Edmonds, File)

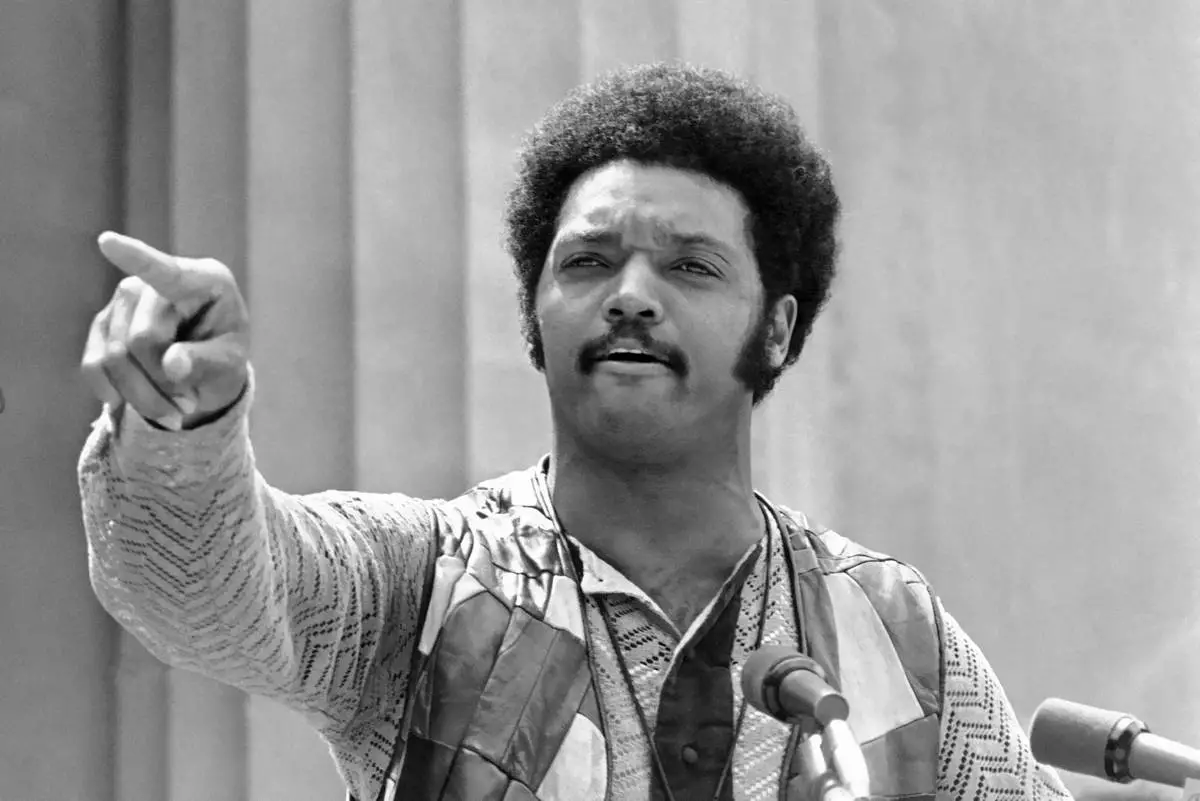

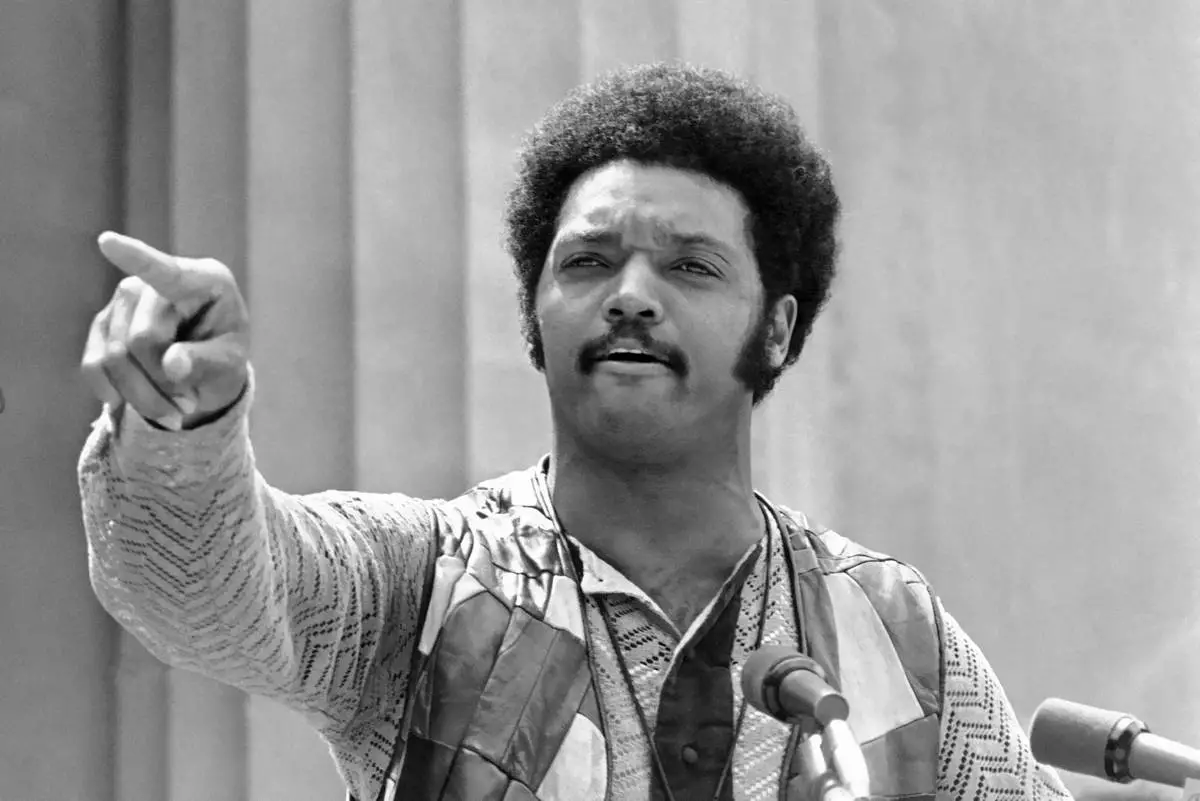

FILE - Jesse Jackson, of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, speaks at a University of California rally on May 27, 1970, at The Greek Theater in Berkeley, Calif. (AP Photo/Sal Veder, File)

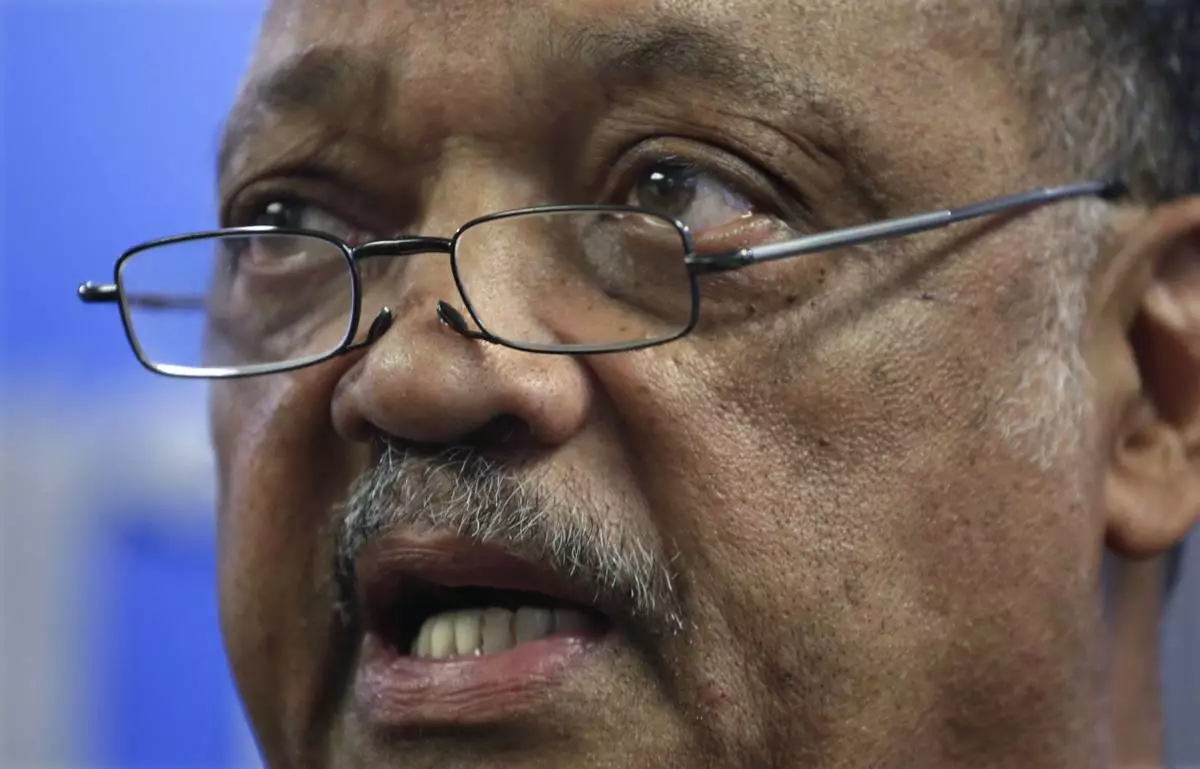

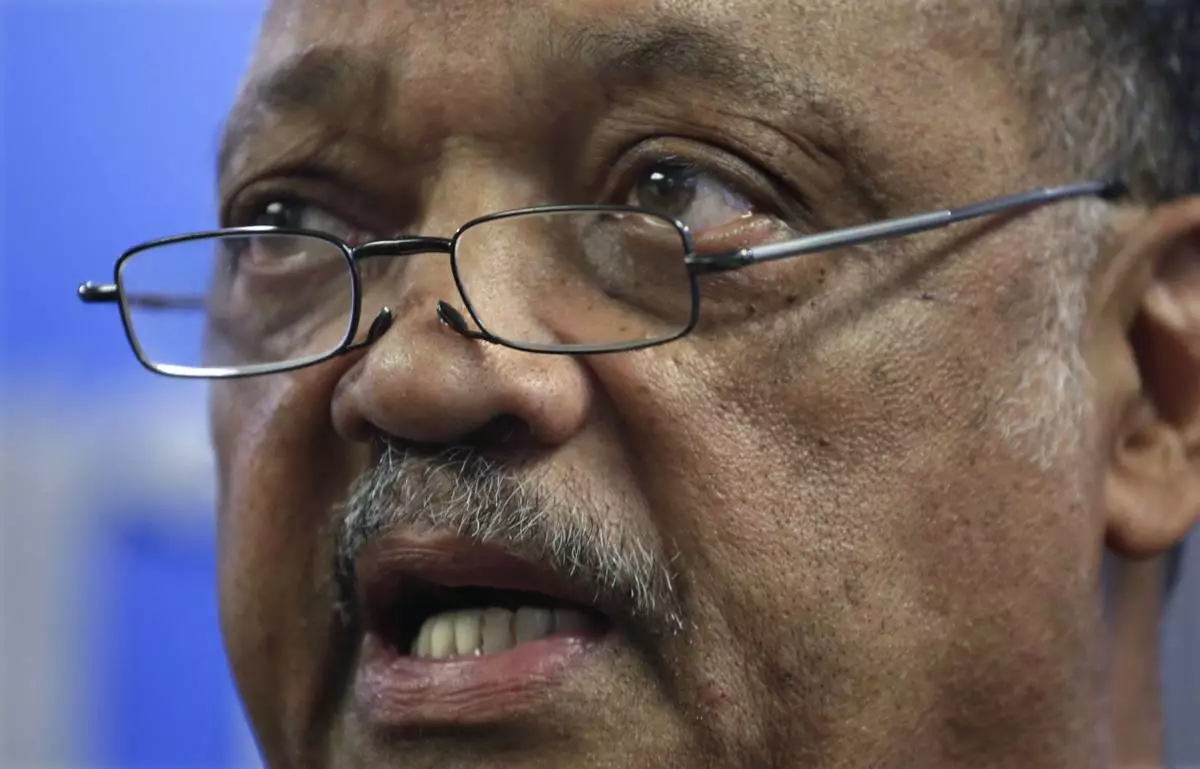

FILE - Jesse Jackson speaks during a press conference regarding Little League International's decision to strip Chicago's Jackie Roberson West baseball team of it's national championship, in Chicago, Feb. 12, 2015. (AP Photo/M. Spencer Green, File)

FILE - Democratic presidential hopeful Jesse Jackson with his wife, Jacqueline, salutes the cheering crowd at Operation Push in Chicago, March 10, 1988. (AP Photo/Fred Jewell, File)

FILE - Rev. Jesse Jackson waves as he steps to the podium during the third day of the Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia, July 27, 2016. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)