SEOUL, South Korea (AP) — Ousted South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol on Friday remained defiant in his first reaction to a life sentence for rebellion handed down by a Seoul court the previous day.

In a statement released by his lawyers, Yoon maintained that his abrupt and short-lived declaration of martial law in December 2024 was done “solely for the sake of the nation and our people,” and dismissed the Seoul Central District Court as biased against him.

Click to Gallery

A protester wearing a mask of South Korean former President Yoon Suk Yeol attends a press conference demanding death sentence for Yoon ahead of the court's verdict in Seoul, South Korea, Thursday, Feb. 19, 2026. The sign at top reads, "Death." (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

Supporters of former South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol stage a rally outside of Seoul Central District Court in Seoul, South Korea, Thursday, Feb. 19, 2026. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

Supporters of former South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol stage a rally outside of Seoul Central District Court in Seoul, South Korea, Thursday, Feb. 19, 2026. A sign reads "Not Guilty." (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

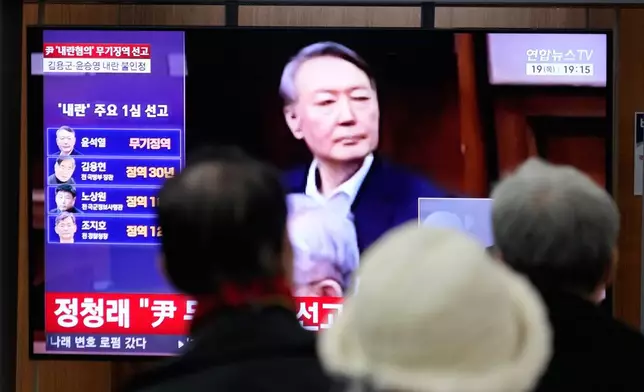

A TV screen shows an image of former South Korea President Yoon Suk Yeol during a news program at the Seoul Railway Station in Seoul, South Korea, Thursday, Feb. 19, 2026. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

Yoon, who was removed from office amid a political crisis set off by his unsuccessful power grab, has long rejected the eight criminal cases brought against him for what prosecutors described as a coup attempt and other allegations.

He barricaded himself in the presidential residence for weeks, stonewalled investigators following his arrest, and skipped court dates, while clashing with witnesses when he did appear.

In handing down his verdict on rebellion charges on Thursday, Judge Jee Kui-youn of the Seoul court said that Yoon has shown “no sign of apology for the staggering social costs incurred by the emergency martial law” and that he “refused to appear in court without any justifiable reason” several times.

Conservative supporters of the former president, who rallied near the court for hours ahead of the verdict, expressed disappointment and anger after it was announced, while his opponents cheered in nearby streets, the two groups separated by hundreds of police officers. There were no major clashes.

Yoon's statement rejected the verdict as illegitimate.

“In a situation where the independence of the judiciary cannot be guaranteed and a verdict based on law and conscience is difficult to expect, I feel deep skepticism whether it would be meaningful to continue a legal battle through an appeal,” said Yoon, 65, who has been jailed since last July.

Yoo Jeong-hwa, one of Yoon’s lawyers, said Yoon was “merely expressing his current state of mind” and was not indicating an intention to waive his right to appeal. Yoon has seven days to appeal Thursday’s sentence.

In his statement, Yoon expressed sympathy to the families of soldiers, police officials and public servants facing investigations or indictment in connection with his martial law decree, saying he feels responsible for their suffering. But he also assured his supporters “our fight is not over.”

The court found Yoon guilty of orchestrating a rebellion by mobilizing military and police forces in an illegal bid to seize the liberal-led legislature, arrest political opponents and establish unchecked rule for an indefinite period. Yoon has described his authoritarian push as necessary to counter the opposition-controlled legislature, which he portrayed as made up of “anti-state” forces.

Yoon could also face an appeal brought by an independent counsel, who asked the court to sentence him to death and have the right to ask a higher court to change the sentence. Jang Woo-sung, a member of the investigation team, told reporters after the ruling that the team has “reservations" regarding the court’s factual findings and the severity of the sentence.

The Seoul court also convicted and sentenced five former military and police officials involved in enforcing Yoon’s martial law decree. They included ex-Defense Minister Kim Yong Hyun, who received a 30-year jail term for his central role in planning the measure, mobilizing the military and instructing military counterintelligence officials to arrest key politicians, including current liberal President Lee Jae Myung. Kim has appealed.

Jang Dong-hyuk, leader of the conservative People Power Party, said at a news conference Friday that the court failed to present a convincing case that Yoon’s martial law amounted to rebellion and, referring to a possible appeal, stressed that “the right to be presumed innocent applies to everyone without exception."

Yoon’s martial law decree, announced late at night on Dec. 3, 2024, lasted about six hours, after a quorum of lawmakers broke through a military blockade and unanimously voted to overturn it, forcing his Cabinet to lift the measure.

Yoon was suspended from office on Dec. 14, 2024, after being impeached by lawmakers and was formally removed by the Constitutional Court in April 2025. He has been facing multiple criminal trials under arrest, with the rebellion charge carrying the most severe punishment.

While brief, Yoon’s martial law decree set off the country’s most severe political crisis in decades, paralyzing politics and high-level diplomacy and rattling financial markets. The power vacuum was resolved after Lee won an early election in June last year.

A protester wearing a mask of South Korean former President Yoon Suk Yeol attends a press conference demanding death sentence for Yoon ahead of the court's verdict in Seoul, South Korea, Thursday, Feb. 19, 2026. The sign at top reads, "Death." (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

Supporters of former South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol stage a rally outside of Seoul Central District Court in Seoul, South Korea, Thursday, Feb. 19, 2026. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

Supporters of former South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol stage a rally outside of Seoul Central District Court in Seoul, South Korea, Thursday, Feb. 19, 2026. A sign reads "Not Guilty." (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

A TV screen shows an image of former South Korea President Yoon Suk Yeol during a news program at the Seoul Railway Station in Seoul, South Korea, Thursday, Feb. 19, 2026. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

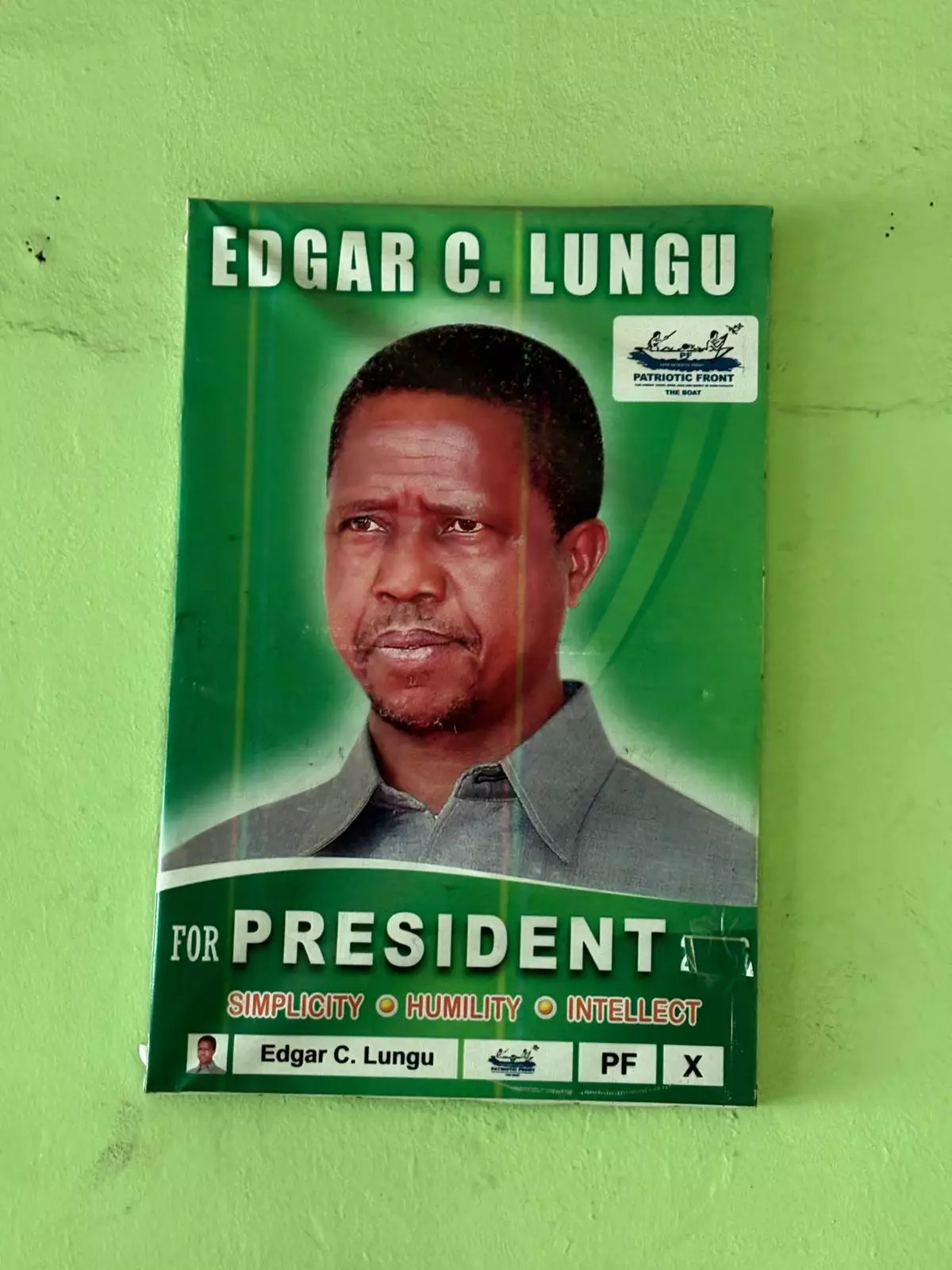

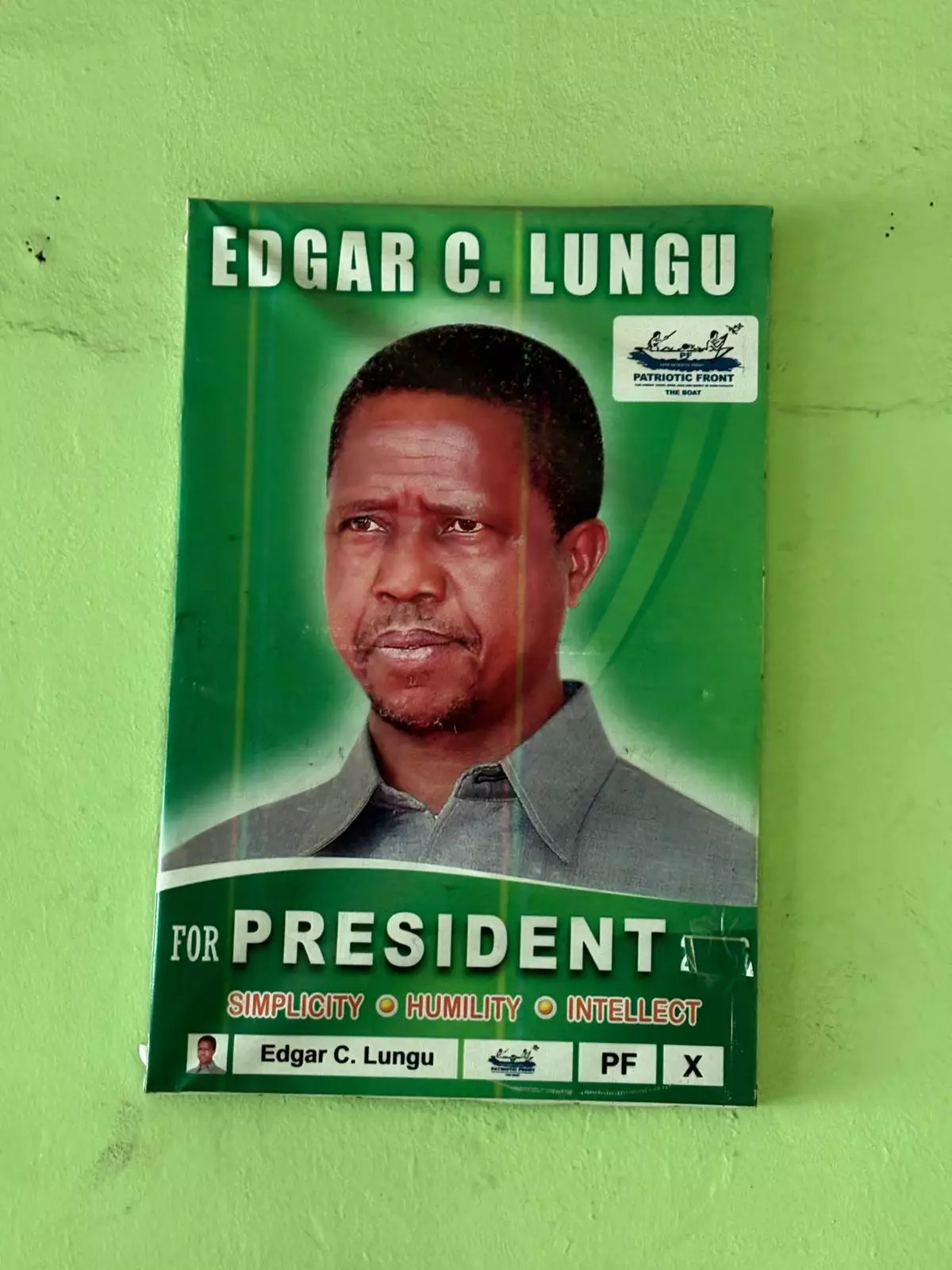

LUSAKA, Zambia (AP) — More than eight months after his death, former Zambian President Edgar Lungu's remains are still in a South African funeral home, the subject of a macabre fight between his family and the longtime rival who succeeded him.

A graphic symbol of the dispute: an unfilled, coffin-size hole in a cemetery in Zambia’s capital, Lusaka, where the current president, Hakainde Hichilema, had hoped Lungu would be buried in a state funeral. But Lungu, in his last days, told his family members that Hichilema, even as a mourner, should never go near his body.

The matter has gone to the courts, which have repeatedly sided with Zambian authorities over Lungu’s wishes. Lungu’s family persists in seeking a burial that sidelines Hichilema.

So the body lies frozen in South Africa, where Lungu died, while Zambia endures a scandalous saga that offends traditional beliefs and raises many questions in a country where it is taboo to fail to bury the dead promptly and with dignity.

Behind the impasse is a long-running feud between two political rivals. It also reflects a spiritual contest between Hichilema, who is up for reelection in August, and Lungu, who is said to be fighting back from the dead, according to scholars and religious leaders who spoke to The Associated Press.

“It has shifted from the physical, it has shifted from politics, and it is now a spiritual battle,” said Bishop Anthony Kaluba of Life of Christ congregation in Lusaka.

Hichilema’s supporters see Lungu’s will as casting a curse, while they say a state funeral attended by Hichilema would be an act of generosity toward Lungu and his family.

The fight over a corpse can seem bizarre to others, but Lungu’s directive resonates with many Zambians.

Some have barred their enemies from attending their funerals, often blaming them for misfortune. Those quarrels are usually more private, not like the public drama of a former president who, facing death, retaliates against his rival in the harsh language of his ancestors.

Across Africa, last words are a “vital force” to enhance life or block it, said Chammah J. Kaunda, a Zambian professor of African Pentecostal theology who serves as academic dean of the Oxford Center for Mission Studies.

Elders facing death can impose curses or give blessings, and Lungu’s case shows that curses “can acquire a life of their own,” he said.

Zambia is a vibrant democracy. Its founding president was the genial, handkerchief-waving Kenneth Kaunda, who was voted out of power in 1991, despite his status as an independence hero.

Like Kaunda, subsequent presidents have been civilians lacking the military strength of various authoritarians elsewhere in Africa, giving Zambia’s presidential hopefuls the opportunity to run on their own merits.

Even so, there’s a perception that some political leaders — like many of their compatriots — worry they might be bewitched. The feeling is widespread in a country where traditional religion thrives alongside Christianity, and a spoken curse is dreaded by many as spiritually enforceable if provoked by injustice.

“It is a weapon,” said Herbert Sinyangwe of WayLife Ministries in Lusaka. “We believe in our culture that curses work.”

In the case of three recent presidents — Michael Sata, Lungu and Hichilema — suspicion was rampant. The official presidential residence is now thought by many to be under a deadly spell because all the six former presidents are now dead. Hichilema works there but sleeps elsewhere.

Sata, who was president from 2011 to 2014, worried that Hichilema, then an opposition figure, was victimizing him even as he asserted that charms from his own region were stronger. Zambian authorities last year had two men convicted and jailed for allegedly plotting to kill the president by magic. Lungu’s family doesn’t trust Hichilema.

The spot in Lusaka that would be Lungu’s tomb was quickly dug and built before it was known that Lungu’s family had objections, said cemetery caretaker Allen Banda. He warned that a tomb without a corpse was akin to digging “your own grave.”

“If nobody goes there, culturally it’s your body that’s going to go there,” he said.

That Hichilema is willing to risk public anger in opposing Lungu’s family has reinforced the views of those who see a spiritual battle between him and Lungu.

“On the one hand, nearly everything done by the Lungu family so far seems to have been designed to deny Hichilema access to Lungu’s body,” said Sishuwa Sishuwa, a Zambian historian who is a visiting scholar at Harvard. “On the other, Hichilema’s conduct so far suggests that he will do whatever it takes to secure access to Lungu’s corpse, perhaps because the president sees the issue as a matter of life and death.”

Lungu died June 5, 2025, after surgery-related complications. He was 68, and was treated for a narrowing of the esophagus.

To organize a state funeral, Zambian authorities would need to take custody of Lungu’s remains until they were interred. But Lungu’s family resisted Hichilema’s plans during negotiations over funeral proceedings.

They preferred to transport the corpse by private charter and had hoped to keep it at Lungu’s residence at night. They picked three people to look after it during the state funeral that never happened.

When Lungu’s family concluded that their wishes were not likely to be followed, they opted for a private funeral in South Africa. They were moving ahead with that ceremony when they found out that Zambian authorities had blocked it.

A South African court ruled in August that Zambian authorities could take Lungu’s body home for burial.

Bertha Lungu, the former president’s sister, was inconsolable in the courtroom after the ruling, wailing and cursing at Mulilo Kabesha, Zambia’s attorney general, who said it was time to take the corpse home. She asserted that Hichilema wanted the corpse for ritual purposes.

Hichilema denies malice toward Lungu, and has said his Christian faith forbids belief in traditional religion.

Lungu rose to power after Sata’s death in 2014. Sata’s vice president, Guy Scott, was ineligible to seek the presidency in a 2015 vote and Lungu was picked to finish Sata’s term.

His main opponent was Hichilema, a wealthy businessman. It was a close race — Lungu won by under 28,000 votes.

After the 2016 election, won again by Lungu, Hichilema faced treason charges and was jailed for four months for allegedly failing to yield to the presidential motorcade.

Five years later, Lungu lost to Hichilema and said he would retire from politics. He changed his mind in 2023, and Zambian authorities withdrew Lungu’s retirement benefits.

Lungu faced more pressure after his wife and daughter were arrested in 2024 over fraud allegations tied to property acquisition.

When he fell sick, Lungu found it hard to leave Zambia. The government restricted his travels. He managed to slip away to South Africa early in 2025, buying a ticket at the airport counter. The incident was reported by the local press as a security lapse over which an airport manager was fired.

Lungu is “still influencing our politics from the grave,” said Emmanuel Mwamba, a Zambian diplomat who speaks for Lungu’s party. “His issues remain. How he was treated in life and how he was treated in death.”

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

Richard Lungu, a supporter of former Zambian President Edgar Lungu, makes a power fist at the entrance to the headquarters of the opposition Patriotic Front party in Lusaka, Zambia, Thursday, Feb.12, 2026. (AP Photo/Rodney Muhumuza)

Allen Banda, cemetery caretaker, sits near the spot where authorities want to bury former president Edgar Lungu, in Lusaka, Zambia, Thursday, Feb.12, 2026. (AP Photo/Rodney Muhumuza)

A mausoleum holding the remains of Michael Sata, Zambia's fifth president, at the cemetery in the Zambian capital of Lusaka where all of Zambia's former leaders are buried, is photographed Thursday, Feb. 12, 2026 (AP Photo/Rodney Muhumuza)

The spot in a cemetery in Lusaka, Zambia, where authorities want to bury former President Edgar Lungu who died more than eight months ago in South Africa, is photographed Thursday, Feb.12, 2026. (AP Photo/Rodney Muhumuza)

A portrait of former Zambian President Edgar Lungu, who died more than eight months ago in South Africa, is displayed on a wall in Lusaka, Zambia, Thursday, Feb.12, 2026. (AP Photo/Rodney Muhumuza)