TALLINN, Estonia (AP) — Belarusian politician Mikola Statkevich, who was put back in prison after refusing to leave the country as part of a U.S.-brokered release of political prisoners, has been released after suffering a stroke.

Statkevich’s wife, Maryna Adamovich, said Friday that he has trouble speaking from a stroke. “Now he's recovering and gaining strength,” she told The Associated Press in a phone interview from the Belarusian capital.

When Belarus' authoritarian President Alexander Lukashenko pardoned 52 political prisoners in September and they were taken to the Lithuanian border, Statkevich, 69 called the government’s actions a “forced deportation,” pushed his way out of the bus and stayed for several hours in the no-man’s land between the borders before being taken away by Belarusian police and returned to prison.

He was serving a 14-year prison sentence after his arrest in 2020 on charges of organizing mass unrest in a case that human rights groups, including Amnesty International, have described as politically motivated.

Lukashenko’s spokeswoman Natalia Eismont said Friday that the Belarusian leader had ordered the release of Statkevich because of his condition in response to his family’s requests.

Lukashenko, nicknamed “Europe’s last dictator,” has ruled Belarus for over three decades, maintaining his grip on power through relentless crackdown on dissent. Following the 2020 post-election protests that saw hundreds of thousands take to the streets, more than 65,000 people were arrested, thousands were beaten, and hundreds of independent media outlets and nongovernmental organizations were closed and outlawed.

Belarus has faced years of Western isolation and sanctions for its crackdown on human rights and for allowing Moscow to use its territory in the 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Recently, Lukashenko has sought to repair relations with the West, releasing hundreds of political prisoners.

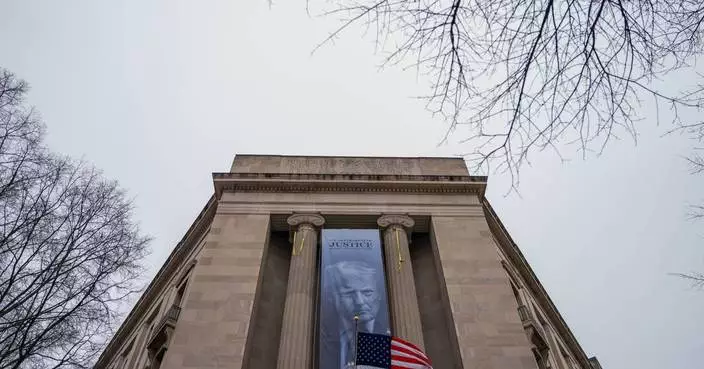

Statkevich was part of a group of prisoners freed weeks after Lukashenko held a phone call with U.S. President Donald Trump in August. In return, sanctions on the country’s national airline, Belavia, were lifted. Another 123 political prisoners, including Nobel Peace Prize laureate Ales Bialiatski, were released on Dec. 13 in exchange for the U.S. lifting some trade sanctions on Belarus.

Despite the recent prisoner releases, the Belarusian authorities have continued their crackdown on dissent. According to the Viasna human rights group, Belarus currently has 1,146 political prisoners.

“It’s still unclear what Statkevich’s legal status is and whether the authorities have cleared the accusations against him,” said Pavel Sapelka of Viasna. “Political repressions in Belarus are continuing, and it means that no government critic can feel secure.”

Sapelka said that Statkevich had spent more than a month in emergency care at a prison hospital after suffering a stroke.

During his decades of political activity, Statkevich, who challenged Lukashenko in a 2010 presidential election, was imprisoned on three occasions and has spent more than 12 years behind bars.

“I feel immense relief that Statkevich is finally free and at home,” Belarusian opposition leader Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, who fled the country in 2020, told the AP. “With his courage and bravery, he won a huge moral victory, for which he paid a high price.”

FILE - Activist Mikalai Statkevich attends a protest in Minsk, Belarus, Sept. 8, 2017. (AP Photo, File)

DUBAI, United Arab Emirates (AP) — Saudi Arabia could have some form of uranium enrichment within the kingdom under a proposed nuclear deal with the United States, congressional documents and an arms control group suggest, raising proliferation concerns as an atomic standoff between Iran and America continues.

U.S. Presidents Donald Trump and Joe Biden both tried to reach a nuclear deal with the kingdom to share American technology. Nonproliferation experts warn any spinning centrifuges within Saudi Arabia could open the door to a possible weapons program for the kingdom, something its assertive crown prince has suggested he could pursue if Tehran obtains an atomic bomb.

Already, Saudi Arabia and nuclear-armed Pakistan signed a mutual defense pact last year after Israel launched an attack on Qatar targeting Hamas officials. Pakistan’s defense minister then said his nation’s nuclear program “will be made available” to Saudi Arabia if needed, something seen as a warning for Israel, long believed to be the Middle East's only nuclear-armed state.

“Nuclear cooperation can be a positive mechanism for upholding nonproliferation norms and increasing transparency, but the devil is in the details,” wrote Kelsey Davenport, the director for nonproliferation policy at the Washington-based Arms Control Association.

The documents raise “concerns that the Trump administration has not carefully considered the proliferation risks posed by its proposed nuclear cooperation agreement with Saudi Arabia or the precedent this agreement may set.”

Saudi Arabia did not respond to questions Friday from The Associated Press.

The congressional document, also seen by the AP, shows the Trump administration aims to reach 20 nuclear business deals with nations around the world, including Saudi Arabia. The deal with Saudi Arabia could be worth billions of dollars, it adds.

The document contends that reaching a deal with the kingdom “will advance the national security interests of the United States, breaking with the failed policies of inaction and indecision that our competitors have capitalized on to disadvantage American industry and diminish the United States standing globally in this critical sector.” China, France, Russia and South Korea are among the leading nations that sell nuclear power plant technology abroad.

The draft deal would see America and Saudi Arabia enter safeguard agreements with the United Nations’ nuclear watchdog — the International Atomic Energy Agency or IAEA. That would include oversight of the “most proliferation-sensitive areas of potential nuclear cooperation,” it added. It listed enrichment, fuel fabrication and reprocessing as potential areas.

“This suggests that once the bilateral safeguards agreement is in place, it will open the door for Saudi Arabia to acquire uranium enrichment technology or capabilities — possibly even from the United States,” Davenport wrote. “Even with restrictions and limits, it seems likely that Saudi Arabia will have a path to some type of uranium enrichment or access to knowledge about enrichment.”

Saudi Arabia is a member state of the IAEA, a Vienna-based agency which promotes peaceful nuclear work but also inspects nations to ensure they don’t have clandestine atomic weapons programs.

The IAEA told the AP in a statement on Friday that it “maintains regular contact with both parties and is able to apply verification measures in connection with bilateral cooperation agreements.”

“If the parties will request the agency to apply verification measures in connection with their bilateral cooperation agreements, the agency will continue to consult with the parties concerned and address the request in accordance with its established procedures,” the IAEA added.

Enrichment isn't an automatic path to a nuclear weapon — a nation also must master other steps including the use of synchronized high explosives, for instance. But it does open the door to weaponization, which has fueled the concerns of the West over Iran's program.

The United Arab Emirates, a neighbor to Saudi Arabia, signed what is referred to as a “123 agreement” with the U.S. to build its Barakah nuclear power plant with South Korean assistance. But the UAE did so without seeking enrichment, something nonproliferation experts have held up as the “gold standard” for nations wanting atomic power.

The push for a Saudi-U.S. deal comes as Trump threatens military action against Iran if it doesn't reach a deal over its nuclear program. The Trump military push follows nationwide protests in Iran that saw its theocratic government launch a bloody crackdown on dissent that killed thousands and saw tens of thousands more reportedly detained.

In Iran's case, it long has insisted its nuclear enrichment program is peaceful. However, the West and the IAEA say Iran had an organized military nuclear program up until 2003. Tehran also had been enriching uranium up to 60% purity, a short, technical step from weapons-grade levels of 90% — making it the only country in the world to do so without a weapons program.

Iranian diplomats long have pointed to 86-year-old Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei's comments as a binding fatwa, or religious edict, that Iran won’t build an atomic bomb. However, Iranian officials increasingly have made the threat they could seek the bomb as tensions have risen with the U.S.

Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, the kingdom's day-to-day ruler, has said if Iran obtains the bomb, “we will have to get one.”

The Associated Press receives support for nuclear security coverage from the Carnegie Corporation of New York and Outrider Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

FILE - President Donald Trump stands with Saudi Arabia's Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman on his visit to the White House, Nov. 18, 2025, in Washington. (AP Photo/Mark Schiefelbein, File)