It's almost as if Letty Stegall is back home in the United States, besides her daughter to wake her for school, fussing over the list when her husband goes shopping, beaming when she sees what her family has managed to cook for dinner.

But Stegall's face only appears on a screen, her words over the phone and in a barrage of texts. Lives once lived together are split by 1,600 miles. A woman who married an American and gave birth to an American and who came to think of herself as American, too, is now deported to her native Mexico.

Click to Gallery

ADVANCE FOR USE MONDAY, JULY 23, 2018 AND THEREAFTER-Jennifer Tadeo-Uscanga, 17, communicates with her mother, Letty Stegall, on a smartphone in the Kansas City, Mo., the home they had shared with Stegall's husband, on Thursday, May 24, 2018. Stegall lived in the United States for 20 years before she was deported back to Mexico in March, leaving behind an American husband and daughter. (AP Photo/Charlie Riedel)

ADVANCE FOR USE MONDAY, JULY 23, 2018 AND THEREAFTER-Letty Stegall, left, takes a selfie photo with her visiting daughter, Jennifer Tadeo-Uscanga, and nephew at the Malecón area of Veracruz, Mexico, on June 7, 2018. “I wish I was there. That’s all that I want,” she says of her life in Kansas City, Mo. “I want my family back.” (AP Photo/Felix Marquez)

ADVANCE FOR USE MONDAY, JULY 23, 2018 AND THEREAFTER-Steve Stegall talks to a cook at his hockey bar, The Blue Line, in Kansas City, Mo., on Thursday, May 24, 2018. Stegall has taken on many of the duties once performed by his wife, Letty Stegall, who was the general manager until she was deported back to Mexico in March. (AP Photo/Charlie Riedel)

ADVANCE FOR USE MONDAY, JULY 23, 2018 AND THEREAFTER-Letty Stegall is overwhelmed by emotion after talking to her daughter and watching the security cameras at the bar she manages back in Kansas City, Mo., as she sits at a table in her parents' home in Boca Del Rio, Veracruz state, Mexico on Thursday, May 24, 2018. Stegall, who is married to an American and has an American daughter, was deported to Mexico in March. “I wish I was there. That’s all that I want,” she says of her life in the U.S. “I want my family back.” (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

ADVANCE FOR USE MONDAY, JULY 23, 2018 AND THEREAFTER-In this May 24, 2018 photo, Jennifer Tadeo-Uscanga, 17, and her stepdad, Steve Stegall, stand outside the Kansas City, Mo., home they shared with wife and mother Letty Stegall. Stegall, who lived in the United States for 20 years, was deported back to Mexico in March, leaving the pair to fill the void left by her absence. (AP Photo/Charlie Riedel)

ADVANCE FOR USE MONDAY, JULY 23, 2018 AND THEREAFTER-In this Thursday, May 24, 2018 photo, Jennifer Tadeo-Uscanga, 17, talks about her mother, Letty Stegall, in the Kansas City, Mo., home they shared along with Stegall's husband. Stegall was deported back to Mexico in March, leaving behind an American husband and daughter. “My God,” Jennifer wrote to the immigration judge handling her mother’s case, “my own country has been the one that has caused me pain.” (AP Photo/Charlie Riedel)

ADVANCE FOR USE MONDAY, JULY 23, 2018 AND THEREAFTER-Jennifer Tadeo-Uscanga, 17, communicates with her mother, Letty Stegall, on a smartphone in the Kansas City, Mo., the home they had shared with Stegall's husband, on Thursday, May 24, 2018. Stegall lived in the United States for 20 years before she was deported back to Mexico in March, leaving behind an American husband and daughter. (AP Photo/Charlie Riedel)

ADVANCE FOR USE MONDAY, JULY 23, 2018 AND THEREAFTER-Letty Stegall, left, takes a selfie photo with her visiting daughter, Jennifer Tadeo-Uscanga, and nephew at the Malecón area of Veracruz, Mexico, on June 7, 2018. “I wish I was there. That’s all that I want,” she says of her life in Kansas City, Mo. “I want my family back.” (AP Photo/Felix Marquez)

ADVANCE FOR USE MONDAY, JULY 23, 2018 AND THEREAFTER-Steve Stegall talks to a cook at his hockey bar, The Blue Line, in Kansas City, Mo., on Thursday, May 24, 2018. Stegall has taken on many of the duties once performed by his wife, Letty Stegall, who was the general manager until she was deported back to Mexico in March. (AP Photo/Charlie Riedel)

ADVANCE FOR USE MONDAY, JULY 23, 2018 AND THEREAFTER-Letty Stegall is overwhelmed by emotion after talking to her daughter and watching the security cameras at the bar she manages back in Kansas City, Mo., as she sits at a table in her parents' home in Boca Del Rio, Veracruz state, Mexico on Thursday, May 24, 2018. Stegall, who is married to an American and has an American daughter, was deported to Mexico in March. “I wish I was there. That’s all that I want,” she says of her life in the U.S. “I want my family back.” (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

ADVANCE FOR USE MONDAY, JULY 23, 2018 AND THEREAFTER-In this May 24, 2018 photo, Jennifer Tadeo-Uscanga, 17, and her stepdad, Steve Stegall, stand outside the Kansas City, Mo., home they shared with wife and mother Letty Stegall. Stegall, who lived in the United States for 20 years, was deported back to Mexico in March, leaving the pair to fill the void left by her absence. (AP Photo/Charlie Riedel)

ADVANCE FOR USE MONDAY, JULY 23, 2018 AND THEREAFTER-In this Thursday, May 24, 2018 photo, Jennifer Tadeo-Uscanga, 17, talks about her mother, Letty Stegall, in the Kansas City, Mo., home they shared along with Stegall's husband. Stegall was deported back to Mexico in March, leaving behind an American husband and daughter. “My God,” Jennifer wrote to the immigration judge handling her mother’s case, “my own country has been the one that has caused me pain.” (AP Photo/Charlie Riedel)

ADVANCE FOR USE MONDAY, JULY 23, 2018 AND THEREAFTER-Jennifer Tadeo-Uscanga, 17, communicates with her mother, Letty Stegall, on a smartphone in the Kansas City, Mo., the home they had shared with Stegall's husband, on Thursday, May 24, 2018. Stegall lived in the United States for 20 years before she was deported back to Mexico in March, leaving behind an American husband and daughter. (AP Photo/Charlie Riedel)

"I lost everything," she says. "It's just me."

As the United States takes a harder line on immigration, thousands who called the country home are being forced to go. Often, they leave behind spouses and children with American citizenship and must figure out how to go on with families fractured apart.

Studies have found an estimated 8 million to 9 million Americans — the majority of them children — live with at least one relative who is in the country illegally, and so each action to deport an immigrant is just as likely to entangle a citizen or legal U.S. resident.

ADVANCE FOR USE MONDAY, JULY 23, 2018 AND THEREAFTER-Letty Stegall, left, takes a selfie photo with her visiting daughter, Jennifer Tadeo-Uscanga, and nephew at the Malecón area of Veracruz, Mexico, on June 7, 2018. “I wish I was there. That’s all that I want,” she says of her life in Kansas City, Mo. “I want my family back.” (AP Photo/Felix Marquez)

Stegall was 21 when she paid a smuggler to take her across the Rio Grande in 1999. She settled around Kansas City, Missouri, and over time, her fear of being caught receded. Then six years ago, police pulled her over and charged her with misdemeanor drunken driving. The arrest made authorities aware she was in the U.S. illegally and plunged her case into the immigration system.

By then, Stegall was divorced from her first husband, with whom she had a daughter, and was dating Steve Stegall, a native of Kansas City whom she married later that same year. She never applied for a green card because her former attorney told her she had little to worry about with a citizen husband and child and because, under U.S. law, she likely would have had to return to Mexico and wait out the process there.

Barack Obama was still president when Stegall received a deportation order, and like many at that time, she was allowed to stay in the U.S. while she made regular check-ins with Immigration and Customs Enforcement. An executive order issued by President Donald Trump changed ICE's direction, effectively declaring any immigrant without legal status subject to arrest. Even the path is once seen as simplest to legal status — marriage to a citizen — no longer is always enough to stave off deportation.

ADVANCE FOR USE MONDAY, JULY 23, 2018 AND THEREAFTER-Steve Stegall talks to a cook at his hockey bar, The Blue Line, in Kansas City, Mo., on Thursday, May 24, 2018. Stegall has taken on many of the duties once performed by his wife, Letty Stegall, who was the general manager until she was deported back to Mexico in March. (AP Photo/Charlie Riedel)

On Feb. 26, as Stegall backed out of her driveway to head to the gym, three cars careened in and agents arrested her. Four days later, she was shackled aboard a plane and headed back to Mexico.

While ICE often touts the criminal convictions of those it picks up, arrests for convictions like driving under the influence (59,985 in the fiscal year 2017) outnumber those of immigrants previously convicted for homicide, sexual assault or kidnapping. (Those collectively totaled 6,553 in 2017.) Meantime, arrests of immigrants without criminal convictions have increased since Trump took office.

"The murderers are still there. The gangsters are still there. Therapists are still there," says Stegall, 41.

ADVANCE FOR USE MONDAY, JULY 23, 2018 AND THEREAFTER-Letty Stegall is overwhelmed by emotion after talking to her daughter and watching the security cameras at the bar she manages back in Kansas City, Mo., as she sits at a table in her parents' home in Boca Del Rio, Veracruz state, Mexico on Thursday, May 24, 2018. Stegall, who is married to an American and has an American daughter, was deported to Mexico in March. “I wish I was there. That’s all that I want,” she says of her life in the U.S. “I want my family back.” (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Stegall's deportation means she could be banned from the U.S. for a decade. She prays paperwork seeking to validate her return through her marriage could wind through the system within two years.

Back in Kansas City, her husband, Steve, and 17-year-old daughter, Jennifer Tadeo-Uscanga, are lumbering along without her. Dinners, once an ever-changing parade of feasts that charmed the palates of Steve and Jennifer, have become spartan affairs. Plants wilted and died, and clothes came out of the wash tinged in blue. Celebrations now typically include tears.

ADVANCE FOR USE MONDAY, JULY 23, 2018 AND THEREAFTER-In this May 24, 2018 photo, Jennifer Tadeo-Uscanga, 17, and her stepdad, Steve Stegall, stand outside the Kansas City, Mo., home they shared with wife and mother Letty Stegall. Stegall, who lived in the United States for 20 years, was deported back to Mexico in March, leaving the pair to fill the void left by her absence. (AP Photo/Charlie Riedel)

"She's not dead," says Jennifer, who was born in the Kansas City area. "But she's not here."

Stegall's in-laws have put off retiring because they're needed at the family bar she helped run. Steve is depressed and hustling to keep up with his wife's absence at the business. Most of all, though, a teen has been left broken by her mother's departure.

Jennifer went to prom with no one to help her primp, blew out her birthday candles without the woman she calls her best friend, and heads toward senior year, graduation, and college with her excitement dulled because her closest confidante won't be there to see any of it.

"My God," Jennifer wrote to the immigration judge handling her mother's case, "my own country has been the one that has caused me pain."

ADVANCE FOR USE MONDAY, JULY 23, 2018 AND THEREAFTER-In this Thursday, May 24, 2018 photo, Jennifer Tadeo-Uscanga, 17, talks about her mother, Letty Stegall, in the Kansas City, Mo., home they shared along with Stegall's husband. Stegall was deported back to Mexico in March, leaving behind an American husband and daughter. “My God,” Jennifer wrote to the immigration judge handling her mother’s case, “my own country has been the one that has caused me pain.” (AP Photo/Charlie Riedel)

For her part, Stegall is now a stranger in a vaguely familiar land.

Her phone and computer remain her link to the life that was once hers. When Jennifer gets home from school, Stegall is there on FaceTime to greet her. She watches streaming feeds from 16 cameras at the family bar she manages remotely. She presses her lips to her screen to give Steve a goodnight kiss.

The long-distance connections get her through the day, but she sees them all as a cheap substitute for what she had as she endures a long wait for a resolution.

"An hour is a month," she says. "A month is a year."

North Carolina could lose nearly $50 million in federal funding if the state doesn't revoke commercial driver's licenses from immigrants who aren't qualified to hold them after an audit uncovered problems, the U.S. Transportation Department said Thursday.

North Carolina is the ninth state to be targeted since Transportation Secretary Sean Duffy launched the nationwide review last year to make sure only qualified drivers hold licenses to drive semitrailer trucks or buses.

The issue started to generate headlines after a truck driver who was not authorized to be in the U.S. made an illegal U-turn and caused a crash in Florida that killed three people in August.

The Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration reviewed 50 commercial driver's licenses that North Carolina had issued to immigrants in its audit and found problems with more than half of them. That's what prompted the threat to withhold funding if the state doesn't clean up its licensing program. Records show that 924 of these kind of licenses remain unexpired in North Carolina.

“North Carolina’s failure to follow the rules isn’t just shameful — it’s dangerous," Duffy said.

North Carolina DMV spokesman Marty Homan said the state is working to address the concerns and remains “committed to upholding safety and integrity in our licensing processes.”

Duffy has pulled nearly $200 million from California over concerns about that state's licensing practices and its decision to delay the revocations of more than 17,000 invalid licenses. Duffy also said that California isn’t enforcing English proficiency requirements for truckers.

He also previously threatened to withhold millions of dollars in federal funding from Pennsylvania, Minnesota, New York, Texas, South Dakota, Colorado, and Washington after audits found significant problems under the existing rules, including commercial licenses being valid long after an immigrant truck driver’s work permit expired.

Separately, Tennessee announced Thursday that it launched its own review of commercial driver's licenses and will be notifying about 8,800 of the state's 150,000 commercial driver's license holders that they need to provide proof of citizenship or a valid visa if they want to keep their licenses.

Russell Shoup, who is assistant commissioner of Tennessee's Driver Services Division, said the state is working to make sure all the licenses the state has issued meet current state and federal standards.

The federal crackdown on commercial driver's licensing has been praised by trucking groups. The industry said that too often unqualified drivers who shouldn’t have licenses or can’t speak English have been allowed to get behind the wheel of an 80,000-pound (about 39,916 kilograms) truck. They have also applauded the Transportation Department’s moves to go after questionable commercial driver’s license schools.

But immigrant groups say that some drivers are now being unfairly targeted. The spotlight has been on Sikh truckers because the driver in the Florida crash and the driver in another fatal crash in California in October are both Sikhs. So the Sikh Coalition, a national group defending the civil rights of Sikhs, and the San Francisco-based Asian Law Caucus filed a class-action lawsuit against California over that state's plan to revoke thousands of licenses.

Immigrants account for about 20% of all truck drivers, but these non-domiciled licenses immigrants can receive only represent about 5% of all commercial driver’s licenses or about 200,000 drivers. The Transportation Department also proposed new restrictions that would severely limit which noncitizens could get a license, but a court put the new rules on hold.

Associated Press writer Gary Robertson from Raleigh, North Carolina, contributed to this report.

FILE - Tractor trailers move along Interstate 5, headed north through Fife, Wash., near the Port of Tacoma, Aug. 24, 2016. (AP Photo/Ted S. Warren, File)

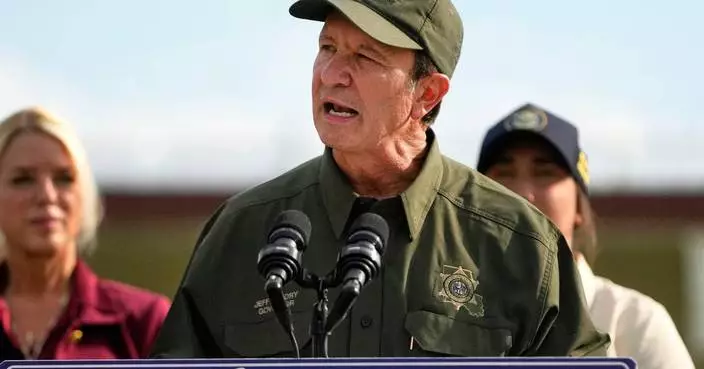

FILE - United States Secretary of Transportation Sean Duffy speaks during a news conference at LaGuardia Airport in New York, Oct. 28, 2025. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig, File)

FILE- Tractor-trailers move cargo out of the Port of Savannah in Savannah, Ga., Jan. 30, 2018. (AP Photo/Stephen B. Morton, File)