Tamara Jenkins has had time to consider why there have been such long stretches between her movies. Her latest, "Private Life ," starring Kathryn Hahn and Paul Giamatti as a New York couple struggling with infertility treatments, comes 11 years after her last one, the Oscar-nominated "The Savages."

For Jenkins' fans, such prolonged absences (it was nine years following her 1998 debut, "The Slums of Beverly Hills") are a disappointment. For others, it's a prime example of how the movie industry doesn't value its female filmmakers like its male ones. For Jenkins, it's more complicated.

Click to Gallery

This image released by Netflix shows filmmaker Tamara Jenkins on the set of "Private Life." Jenkins wrote and directed the film, her first in 11 years. (Jojo WhildenNetflix via AP)

This image released by Netflix shows actor Paul Giamatti, left, with filmmaker Tamara Jenkins on the set of "Private Life." Jenkins wrote and directed the film, her first in 11 years. (Jojo WhildenNetflix via AP)

This image released by Netflix shows actress Kayli Carter, right, with filmmaker Tamara Jenkins on the set of "Private Life." Jenkins wrote and directed the film, her first in 11 years. (Jojo WhildenNetflix via AP)

This image released by Netflix shows Paul Giamatti, left, and Kathryn Hahn in a scene from "Private Life." (Jojo WhildenNetflix via AP)

"When you're in it, you're like: Is it me or is it them? What makes that problem, in terms of myself?" Jenkins wonders. "When I was at Sundance people kept asking me that question. I kept saying, 'Yeah, I know. I'm a loser. How is it possible 11 years went by?' And then I looked around and I realized Patty Jenkins ('Wonder Woman') hadn't made a movie and Debra Granik ('Leave No Trace') hadn't made a feature for years. So I'm not alone."

This image released by Netflix shows filmmaker Tamara Jenkins on the set of "Private Life." Jenkins wrote and directed the film, her first in 11 years. (Jojo WhildenNetflix via AP)

Still, Jenkins adds, there are other factors, too. She and her husband, Jim Taylor (Alexander Payne's frequent writing partner), had a kid in that time period — the experience of which eventually led her to writing "Private Life." And then she's meticulous — "novel-y," she says — in her writing process; she estimates it took two years to write "Private Life," some of that time spent at the upstate New York artists' colony Yadoo (which also figures into the film).

"It's also a desire to not necessarily make any old thing. There are a lot of things out there that might be makeable but aren't good. There are a lot of really bad movies," Jenkins said in a recent interview. "And I never have had an easy time trying to get these things made. Like 'The Savages,' which took place in a nursing home, nobody wants to make that movie. This is different but, still, it doesn't sound sexy on paper."

"Private Life," which premieres on Netflix and in select theaters Friday, is indeed more than its synopsis. Hahn and Giamatti play downtown New York creatives reaching middle age and going through one fertility trial after another. But in Jenkins' hands, "Private Life" is a caustically funny, painfully intimate, medicalized examination of, as she says, "a marriage in the middle." Though much of the plot follows a struggle to conceive, it's ultimately centered on the couple; Giamatti compares it to "Waiting for Godot."

This image released by Netflix shows actor Paul Giamatti, left, with filmmaker Tamara Jenkins on the set of "Private Life." Jenkins wrote and directed the film, her first in 11 years. (Jojo WhildenNetflix via AP)

"People ask me what it's about and I say it's a movie about marriage," says Jenkins. "It's obviously on a very specific journey that they're on. But there was something so existential about that problem for them. It's so primal."

As an on-screen couple, Hahn and Giamatti are remarkably attuned to each other, especially considering they didn't know each other before the film. Jenkins set up a meeting at Giamatti's Brooklyn home for the two to meet and get acquainted.

"I feel something about this movie that I don't feel about many things I've been in. I really love it, and a lot of it is those two women I got to work with," Giamatti said by phone during a break from shooting "Billions."

This image released by Netflix shows actress Kayli Carter, right, with filmmaker Tamara Jenkins on the set of "Private Life." Jenkins wrote and directed the film, her first in 11 years. (Jojo WhildenNetflix via AP)

"I wish Tamara was able to be more prolific. I don't know how much it is her wanting to take that much time with something. I don't think so. I think she'd like to be more prolific," Giamatti adds. "But she's incredibly devoted to the very singular thing she wants to do."

Hahn says that Jenkins during shooting is as passionate about a scene being acted as she was when writing it.

"Tamara, as a director, she's a channeler. She's definitely feeling whatever you're feeling at the same amount of intensity. She can't help it. She will feel alongside of you," Hahn says. "We both understood (Hahn's character) Rachel on a pretty deep level. We kind of mind-melded."

This image released by Netflix shows Paul Giamatti, left, and Kathryn Hahn in a scene from "Private Life." (Jojo WhildenNetflix via AP)

Both Hahn and Giamatti have won raves for their soulful, connected performances, though numerous critics have called Hahn's disarmingly naked performance her best yet.

"It's not lost on me that I feel most seen as a performer and as an artist by women filmmakers. That is for damn sure," says Hahn, who's currently prepping an HBO series directed by Nicole Holofcener.

Jenkins, 56, has regularly turned pieces from her life into her films. "The Slums of Beverly Hills," about a transient, lower-middle class Jewish family in Beverly Hills, was inspired by her own 1970s youth. "The Savages," which starred Laura Linney (she was Oscar nominated, as was Jenkins' script) and Philip Seymour Hoffman, chronicled two siblings dealing with an elderly parent with dementia. It too was partly autobiographical.

Jenkins initially dismissed her own trials having a kid as decent movie fodder ("I was like: No way! I'll never do that! Gross!") only to eventually see the dramatic possibilities of a very common experience.

"There's the sort of famous thing that people say: Why don't you just adopt? — 'just' in italics, like adopting is such an easy thing to do, like you can just walk out and get one of those kids over there," says Jenkins. "If you're trying to have a kid and it's not happening the old-fashioned, regular way, all of the routes of having a kid are really complicated, morally and emotionally and economically and socially. It's all very complicated."

One complication Jenkins would rather not encounter: another long wait until her next film.

"The older you get, if you keep waiting 11 years until your next movie, it's going to get really complicated with the walker and the back problem," she says, laughing. "So I would like to pick up the pace in my own middle age."

Follow AP Film Writer Jake Coyle on Twitter at: http://twitter.com/jakecoyleAP

DUBAI, United Arab Emirates (AP) — Widening protests in Iran sparked by the Islamic Republic's ailing economy are putting new pressure on its theocracy.

Tehran is still reeling from a 12-day war launched by Israel in June that saw the United States bomb nuclear sites in Iran. Economic pressure, intensified in September by the return of United Nations sanctions on the country over its atomic program, has put Iran's rial currency into a free fall, now trading at some 1.4 million to $1.

Meanwhile, Iran's self-described “Axis of Resistance” — a coalition of countries and militant groups backed by Tehran — has been decimated in the years since the start of the Israel-Hamas war in 2023.

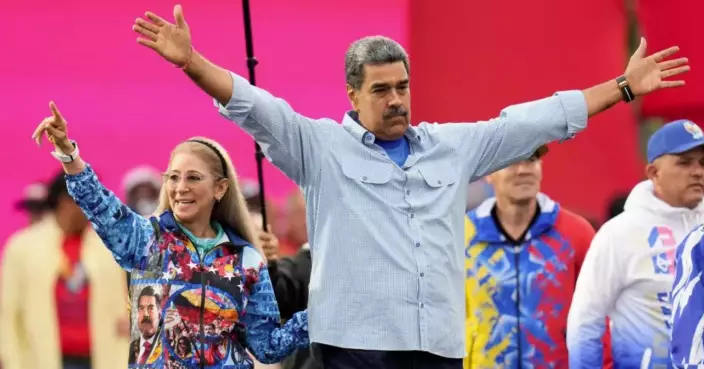

A new threat by U.S. President Donald Trump warning Iran that if Tehran “violently kills peaceful protesters,” the U.S. “will come to their rescue" has taken on new meaning after American troops captured Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro, a longtime ally of Tehran.

Here's what to know about the protests and the challenges facing Iran's government.

Demonstrations have reached over 170 locations in 25 of Iran’s 31 provinces, the U.S.-based Human Rights Activists News Agency reported early Sunday. The death toll had reached at least 15 killed, it added, with more than 580 arrests. The group, which relies on an activist network inside of Iran for its reporting, has been accurate in past unrest.

Understanding the scale of the protests has been difficult. Iranian state media has provided little information about the demonstrations. Online videos offer only brief, shaky glimpses of people in the streets or the sound of gunfire. Journalists in general in Iran also face limits on reporting such as requiring permission to travel around the country, as well as the threat of harassment or arrest by authorities.

But the protests do not appear to be stopping, even after Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei on Saturday said “rioters must be put in their place.”

The collapse of the rial has led to a widening economic crisis in Iran. Prices are up on meat, rice and other staples of the Iranian dinner table. The nation has been struggling with an annual inflation rate of some 40%.

In December, Iran introduced a new pricing tier for its nationally subsidized gasoline, raising the price of some of the world’s cheapest gas and further pressuring the population. Tehran may seek steeper price increases in the future, as the government now will review prices every three months.

The protests began first with merchants in Tehran before spreading. While initially focused on economic issues, the demonstrations soon saw protesters chanting anti-government statements as well. Anger has been simmering over the years, particularly after the 2022 death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini in police custody that triggered nationwide demonstrations.

Iran's “Axis of Resistance," which grew in prominence in the years after the 2003 U.S.-led invasion and subsequent occupation of Iraq, is reeling.

Israel has crushed Hamas in the devastating war in the Gaza Strip. Hezbollah, the Shiite militant group in Lebanon, has seen its top leadership killed by Israel and has been struggling since. A lightning offensive in December 2024 overthrew Iran’s longtime stalwart ally and client in Syria, President Bashar Assad, after years of war there. Yemen's Iranian-backed Houthi rebels also have been pounded by Israeli and U.S. airstrikes.

China meanwhile has remained a major buyer of Iranian crude oil, but hasn't provided overt military support. Neither has Russia, which has relied on Iranian drones in its war on Ukraine.

Iran has insisted for decades that its nuclear program is peaceful. However, its officials have increasingly threatened to pursue a nuclear weapon. Iran had been enriching uranium to near weapons-grade levels prior to the U.S. attack in June, making it the only country in the world without a nuclear weapons program to do so.

Tehran also increasingly cut back its cooperation with the International Atomic Energy Agency, the U.N.'s nuclear watchdog, as tensions increased over its nuclear program in recent years. The IAEA's director-general has warned Iran could build as many as 10 nuclear bombs, should it decide to weaponize its program.

U.S. intelligence agencies have assessed that Iran has yet to begin a weapons program, but has “undertaken activities that better position it to produce a nuclear device, if it chooses to do so.”

Iran recently said it was no longer enriching uranium at any site in the country, trying to signal to the West that it remains open to potential negotiations over its atomic program to ease sanctions. But there's been no significant talks in the months since the June war.

Iran decades ago was one of the United States’ top allies in the Mideast under Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, who purchased American military weapons and allowed CIA technicians to run secret listening posts monitoring the neighboring Soviet Union. The CIA fomented a 1953 coup that cemented the shah’s rule.

But in January 1979, the shah, fatally ill with cancer, fled Iran as mass demonstrations swelled against his rule. Then came the Islamic Revolution led by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, which created Iran’s theocratic government.

Later that year, university students overran the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, seeking the shah’s extradition and sparking the 444-day hostage crisis that saw diplomatic relations between Iran and the U.S. severed.

During the Iran-Iraq war of the 1980s, the U.S. backed Saddam Hussein. During that conflict, the U.S. launched a one-day assault that crippled Iran at sea as part of the so-called “Tanker War,” and later shot down an Iranian commercial airliner that the U.S. military said it mistook for a warplane.

Iran and the U.S. have seesawed between enmity and grudging diplomacy in the years since, and relations peaked with the 2015 nuclear deal, which saw Iran greatly limit its program in exchange for the lifting of sanctions. But Trump unilaterally withdrew America from the accord in 2018, sparking tensions in the Mideast that intensified after Hamas' Oct. 7, 2023, attack on Israel.

FILE - An Iranian security official in protective clothing walks through part of the Uranium Conversion Facility just outside the Iranian city of Isfahan, on March 30, 2005. (AP Photo/Vahid Salemi, File)

FILE - A customer shops at a supermarket at a shopping mall in northern Tehran, on Sept. 28, 2025. (AP Photo/Vahid Salemi, File)

FILE - Current and pre-revolution Iranian banknotes are displayed by a street money exchanger at Ferdowsi square, Tehran's go-to venue for foreign currency exchange, in downtown Tehran, Iran, on Aug. 28, 2025. (AP Photo/Vahid Salemi, File)

FILE - People cross the Enqelab-e-Eslami (Islamic Revolution) street in Tehran, Iran, on Sept. 27, 2025. (AP Photo/Vahid Salemi, File)

FILE - Protesters march on a bridge in Tehran, Iran, on Dec. 29, 2025. (Fars News Agency via AP, File)

People wave national flags during a ceremony commemorating the death anniversary of the late commander of the Iran's Revolutionary Guard expeditionary Quds Force, Gen. Qassem Soleimani, who was killed in a U.S. drone attack in 2020 in Iraq, at the Imam Khomeini grand mosque in Tehran, Iran, Thursday, Jan. 1, 2026. (AP Photo/Vahid Salemi)