The most surprising thing about the fact that Congolese hospitals detain patients who fail to pay their bills is that it's no secret: Administrators, doctors and nurses openly discuss it, and the patients are held in plain sight.

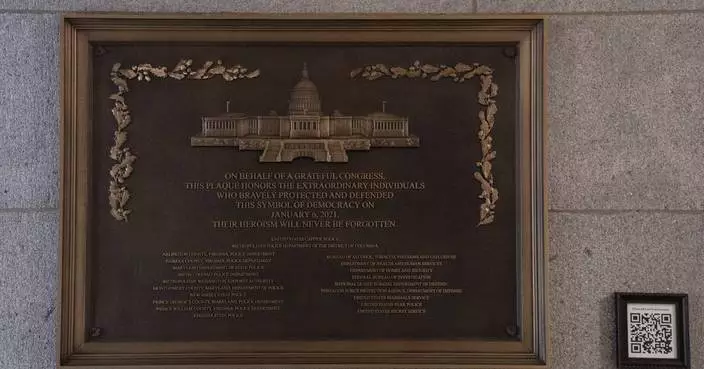

An Associated Press investigation found that only one of more than 20 hospitals and clinics visited in the copper-mining metropolis of Lubumbashi did not routinely imprison patients. Though government officials condemn the illegal practice, and say they stop it when they can, a Ministry of Health official in Kinshasa noted that "health officials cannot be everywhere."

The only ones who claim they don't know what's happening in Congo, it seems, are more than a dozen major health donors and agencies who invest billions of dollars in the country and have major operations there — including the European Union, UNICEF, the International Committee of the Red Cross, PATH, Save the Children, the U.S. Agency for International Development and World Vision. They all told the AP they had no knowledge of patient detentions or insufficient information to act.

Kimenua Ngoie, 22, sits on her hospital bed at the Katuba Reference Hospital in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo on Monday, Aug. 13, 2018. Ngoie, who lost her baby at birth following a C-section, has been effectively imprisoned by the hospital for the past there month, unable to pay the $360 costs of her operation. An Associated Press investigation found that of more than 20 hospitals and clinics visited in Lubumbashi, all but one detain patients, an illegal practice according to the Congolese penal code. (AP PhotoJerome Delay)

EDITOR'S NOTE — Second of two stories on hospital detentions.

But such imprisonment practices would be obvious to anyone who follows a long, dark corridor at the Katuba Reference Hospital to a grimy, roach-infested room that houses the hospital's longest-staying residents: Kimenua Ngoie, who has been there for nearly four months since losing her first baby in a complicated cesarean section and Gabriel Mutamba, in his 80s, who arrived with a broken leg more than a year ago.

Though Ngoie and Mutamba are now healthy enough to be discharged, they have been effectively imprisoned because they cannot pay. Ngoie's bill stands at $360 while Mutamba's is $1,477.

Gabriel Mutamba lies on his hospital bed at the Katuba Reference Hospital in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo on Monday, Aug. 13, 2018. Mutamba, in his 80s, was first brought to the hospital in 2017 by a church group that found him with a broken leg. Though doctors fixed his leg in surgery, he subsequently developed other problems. While he's now stable enough to leave, he's also racked up a substantial bill and hospital officials have so far refused to discharge him. One of the hospital's cleaning women took pity on Mutamba and occasionally brings him food but otherwise, he has few visitors and no family offering to help clear his bill. (AP PhotoJerome Delay)

"There is a God so I'm not afraid to give birth again," said Ngoie, 22. "But my deepest desire right now is just to leave the hospital."

Such detentions are not unusual, in Congo, across much of Africa or in places ranging from the Philippines to Bolivia.

"When we detain patients, this is not something that is unique to our hospital," said Leedy Nyembo-Mugalu, administrator of the Katuba Reference Hospital. "This happens everywhere."

This Tuesday, Aug. 14, 2018 photo shows hospital beds at the Masaidiano Health Center in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo. An Associated Press investigation found that of more than 20 hospitals and clinics visited in Lubumbashi, all but one detain patients, an illegal practice according to the Congolese penal code. Many hospitals lack running water and regular electricity and bed shortages are often so severe that two patients must squeeze onto a single mattress. (AP PhotoJerome Delay)

For the hospitals, holding patients is mostly an act of financial desperation. Most lack basic drugs, running water and regular electricity. Bed shortages are often so severe that two patients must squeeze onto a single mattress. At the Katuba Reference Hospital, sterilizing surgical tools means placing them in a pot of boiling water.

"It's very hard when we have to detain somebody, but we have to recuperate the costs of the products we use, or else we can't treat other patients," said Dr. Veronique Kashala at the Centre Medicale de la Victoire.

Kashala recalled a baby girl who was held for a month this spring after being treated for meningitis, when her family failed to pay $63.

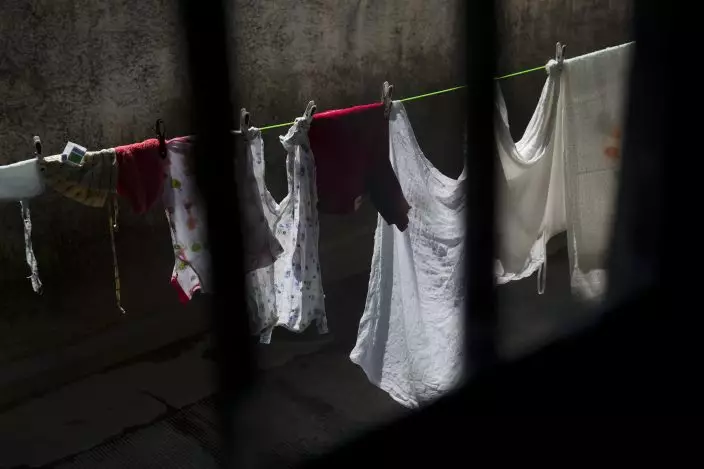

This Tuesday, Aug. 14, 2018 photo shows laundry hanging to dry outside a room used as a maternity ward at the Masaidiano Health Center in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo. An Associated Press investigation found that of more than 20 hospitals and clinics visited in Lubumbashi, all but one detain patients who cannot pay their bills. While some hospitals detain patients for weeks or months before giving up, the AP found one patient trapped for more than a year and obtained documentation on another person held for about two years. (AP PhotoJerome Delay)

The infant's parents finally brought in their pastor, who contributed about $50. That was enough to convince the clinic to release her.

Mike Ahern, Congo field coordinator for the International Rescue Committee, was touring a Goma hospital with which the IRC was partnering when he saw about a half-dozen women sitting on the ground in a room that had bed frames, but no mattresses. He asked why they were on the floor.

"The response was very simple: 'We make them sit on the floor to encourage them to pay'," he recalled, adding that one woman had been there more than a month and all of them owed between $50 and $200.

Karena Anny, 30, holds her baby at the Masaidiano Health Center in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo on Tuesday, Aug. 14, 2018. Anny has been detained at the hospital for a month, unable to pay the $400 cost of her cesarian delivery. (AP PhotoJerome Delay)

Ahern arranged for the IRC to pay to get the women released, within the confines of its project. It was, he said, "only a Band-Aid solution"; once IRC left, the problem would inevitably resurface.

Given how brazenly transparent hospitals are about imprisoning patients in Congo, it is difficult believe that international agencies in Congo could be unaware of patient detentions.

At Lubumbashi's Sendwe Hospital, Columbia University's ICAP and other partners run an AIDS program funded by the U.S. President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (known as PEPFAR). The program is housed in a separate, recently built unit on the hospital grounds — just a short walk away from the hospital's maternity center. There, seven women who couldn't pay their delivery charges were being detained with their babies in early August in a ward with gaping holes in the ceiling.

This Tuesday, Aug. 14, 2018 photo shows the entrance of the Masaidizi Health Center, which was recently built by the United Nations in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo. The health compound's four buildings are painted in white and U.N. blue, although the hospital is now run by the Congolese ministry of health and receives no ongoing U.N. support. (AP PhotoJerome Delay)

Dr. Juliana Soares Linn, ICAP's principal investigator in Congo, said the program had been working in the country on AIDS since 2010 and has "very close relationships" with hospital directors. She declined to comment on whether ICAP had ever seen patient detentions in Congo; PEPFAR, which has invested about a half a billion dollars in Congo's health system since 2004, also declined comment.

At Lubumbashi's Hopital General de Reference Kenya, where stickers showed that many of the computers, printers and even office fans were paid for by USAID, administrator Aimerance Kapapa said some detained patients sweep hallways, mop corridors or mow the grass to offset their debt.

A spokesman for USAID, speaking only on condition of anonymity, would only say the agency was working to ensure that "unexpected (health) costs do not cause undue financial burden on families." The agency did not respond to questions about whether it was aware of hospital detention practices in Congo or elsewhere.

Toussain Kanyimb Nawej shows goods left as collateral by patients unable to pay their bills at the Katuba Reference Hospital in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo on Wednesday, Aug. 15, 2018. Hospital data obtained by The Associated Press in Congo suggest imprisonment is common in both public and private facilities, including those that receive free drugs for AIDS, malaria and reproductive health care from U.S. partners including Columbia University in New York, USAID, and the U.S. President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, or PEPFAR. (AP PhotoJerome Delay)

Some organizations, such as the Global Fund, make grants contingent on countries upholding certain standards. The fund has invested about $1.5 billion in Congo, mostly for programs for HIV, tuberculosis and malaria, including hospitals and health centers, and its contracts specify that medical detentions "are to be used only as a last resort."

Nicolas Farcy, who runs the fund's Congo portfolio, says fund staffers have never encountered hospital detentions.

Karen Cowgill, an assistant professor at the University of Washington who has studied patient detentions in Congo, said external agencies should at least acknowledge publicly that patient detentions occur, so that the issue can be addressed by the wider community.

Alice Kabuya, 20, right, looks at a clinic employee at the Masaidizi Health Center in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo on Tuesday, Aug. 14, 2018. Kabuya gave birth to her daughter at the facility but is unable to pay the $150 medical bill. She said the clinic's doors were locked every afternoon and that she could not walk more than about 10 feet outside before being reprimanded by nurses. (AP PhotoJerome Delay)

The donors, she said, tend to stick to specific programs, like those for AIDS, rather than investing in general health care. "It's really tough because donors are worried about their funds disappearing in a broken system, so they just focus on how their particular program is working," she said.

Robert Yates, a health policy expert at the British think tank, Chatham House, said the World Health Organization could at the very least issue a resolution condemning the practice; the agency issued 16 such statements at their annual meeting this year, including some on snake bites and rheumatic fever.

"As part of their drive for universal health care, WHO could sit down all the health ministers and say we publicly commit to ensuring we're not illegally locking up people in our health facilities," he said. "As uncomfortable as this might be for everyone, the U.N., governments and donors need to confront this issue as a human rights abuse and then actively monitor this so that it can be officially banned and ended."

Alice Kabuya, 20, stands in the Masaidizi Health Center in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo on Tuesday, Aug. 14, 2018. She gave birth to her daughter at the facility and cannot pay the $150 medical bill. Her jobless husband is trying to gather the funds so she had their daughter can be released. (AP PhotoJerome Delay)

But it is admittedly challenging for such institutions to ensure that hospitals like the Centre de Sante Masaidizi — a facility built and paid for by the United Nations — are sufficiently funded so they can operate without holding patients for ransom, as they effectively did with Alice Kabeya, a young mother detained there with her newborn daughter in August. She said the clinic's doors were locked every afternoon and that she could not walk more than about 10 feet outside without being reprimanded by nurses.

Administrators at the Polyclinique Medicare said they would have to shut their doors if patients like 3-year-old Adrielle Nyembwe didn't pay. The boy was being held at the central Lubumbashi clinic in August after being treated for sickle-cell anemia. He had been medically cleared to be released, but had an outstanding bill of $850.

"Nobody in our family has the money to pay," said Adrielle's 23-year-old mother, Ado Ntanga, cradling him in her arms. "I hope we can find someone to help us soon. Because if it's up to the hospital, we will never be free."

Alice Kabuya, 20, holds her week-old daughter at the Masaidizi Health Center in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo on Tuesday, Aug. 14, 2018. Kabuya is unable to pay the $150 medical bill and her jobless husband is trying to gather the funds so she had their daughter can be released. Kabuya said most days she only drinks tea because food is only sporadically provided by the hospital. (AP PhotoJerome Delay)

More than two months later, Adrielle is still being detained at the clinic.

For some, the fear that a hospital stay might be interminable seems very real. At Sendwe Hospital, Lubumbashi's biggest public institution, a few surgical patients were detained for five to six years, according to Abel Ntambue, a Congolese doctor at the University of Lubumbashi. Ntambue said the patients lacked the means to pay for their treatment and that Sendwe eventually released them when they needed the space.

At the Polyclinique Goschen, medical director Dr. Disashi Tshimpuki described the case of a former soldier who was detained for nearly two years. Both of his legs had been amputated after he developed gangrene; his family had paid only a fraction of the $9,290 bill.

A set of keys hangs from a door lock inside the Masaidizi Health Center in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo on Tuesday, Aug. 14, 2018. An Associated Press investigation focused in Congo's second city, the copper-mining metropolis of Lubumbashi, discovered that of more than 20 hospitals and clinics visited, all but one detain patients unable to pay their bills. The practice is illegal according to the Congolese penal code. (AP PhotoJerome Delay)

"At first, he had a lot of family that came to visit him," Tshimpuko said, "but then they deserted him."

Online:

A selection of the hospital detention records obtained by the AP:

https://www.documentcloud.org/search/projectid:41082-Hospital-Hostages

Ado Ntanga, 23, holds her son, Adrielle Nyembwe, 3, who was admitted to the Medicare Policlinic with Sickle Cell Anemia in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo on Wednesday, Aug. 15, 2018. They have both been detained for over a month, unable to pay the $850 medical bill for Adrielle. (AP PhotoJerome Delay)

A child plays under a sign reading, "health center built with funding from Taiwan World Vision Funds" at the Mama Wa Mapendo clinic in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo on Tuesday, Aug. 14, 2018. An Associated Press investigation focused in Congo's second city, the copper-mining metropolis of Lubumbashi, discovered that of more than 20 hospitals and clinics visited, all but one detain patients unable to pay their bills. The practice is illegal according to the Congolese penal code. (AP PhotoJerome Delay)

A patient stands in a doorway at the Katuba Reference Hospital in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo on Monday, Aug. 13, 2018. Across Africa, hospital detentions have been flagged as a problem here and in other countries including Cameroon, Mali, Uganda, South Africa, Zimbabwe. (AP PhotoJerome Delay)