After a spellbinding five-day trial that featured tales of infidelity and a multimillion dollar insurance payout, a jury on Friday convicted a Florida woman of helping mastermind the killing of her husband nearly two decades ago.

Jurors found Denise Williams guilty of three counts including first-degree murder and conspiracy to commit murder for her role in a case that has recalled the plot of the Hollywood film classic "Double Indemnity." The 48-year-old Williams was found guilty after testimony by a key witness, the man who shot her husband Mike Williams on a cold December morning on a large lake west of Tallahassee.

Jurors deliberated eight hours before reaching a verdict. Denise Williams, who could spend the rest of her life in prison, is to be sentenced at an unspecified date next year.

FILE - In this Wednesday, Dec. 12, 2018 file photo, Brian Winchester sits on the witness stand during cross-examination in the trial of Denise Williams in Tallahassee, Fla. Williams, of Florida, has been convicted of helping mastermind the killing of her husband nearly two decades ago. Jurors convicted Williams of first-degree murder Friday, Dec. 14, 2018, and conspiracy to commit murder for the shooting death of her husband Mike Williams. (Alicia DevineTallahassee Democrat via AP, Pool, File)

Mike Williams disappeared nearly 18 years ago to the date of his wife's conviction. He left early on the morning of Dec. 16, 2000, to go duck hunting, and initially some speculated he had fallen from his boat and that his body had been devoured by alligators. His disappearance triggered a massive search by authorities.

But Brian Winchester, who had been Mike Williams's best friend, said he and Denise Williams were having an affair and that they planned the killing. Denise Williams ultimately received $1.75 million in life insurance payments, including a $1 million policy that Winchester himself had sold Mike Williams.

In the film "Double Indemnity," an insurance agent helps his lover kill her husband in order to cash in on a life insurance policy.

Winchester said he planned to make it look like Williams had drowned. But after pushing him overboard, Williams did not get dragged underwater by his duck-hunting equipment. So Winchester said he shot him in the face with a 12-gauge shotgun. He then dragged his body to shore, put him in the back of his truck and drove back to Tallahassee. He eventually buried him later in the day alongside a small lake located north of town.

Without a body, Denise Williams petitioned to have her husband declared dead due to accidental drowning. Winchester and Denise Williams married in 2005 but the relationship soured and they divorced in 2016.

The case broke after Winchester kidnapped his ex-wife at gunpoint in 2016, authorities said. He eventually made a deal with prosecutors and was sentenced to 20 years in prison for that crime. But Winchester ultimately led authorities to the remains of Mike Williams.

Ethan Way, an attorney for Denise Williams, told jurors during closing statements that his client was innocent and that there was no tangible proof that Denise Williams helped plan the slaying of Mike Williams. Instead he maintained that Winchester was lying in order to avoid murder charges and get revenge on his ex-wife.

"They gave a free pass to a murderer and got nothing else," Way told jurors in his closing statement.

State Attorney Jon Fuchs told jurors it "turns my stomach" that prosecutors gave Winchester immunity in the case, but he said it was important to give "closure" to other members of the Williams family who had suspected for years that Mike Williams did not drown. Fuchs said that Winchester would still be in prison for a long time.

Right before he ended, Fuchs took something out of his pocket and placed it before the jury: It was the wedding band that Mike Williams was wearing the day he died.

Some friends and relatives of Mike Williams sobbed quietly after the verdict and louder yet after the jury left the courtroom. Cheryl Williams, the mother of Mike Williams, thanked prosecutors for their work on the case.

"I am just happy we were able to do our job as a team and bring justice to Mike and his family," Fuchs said afterward. He added "it's not every day in your career that you get to be involved in an unsolved homicide that's 17 years old and through team effort able to make an arrest and ultimately get a conviction."

Way said his client Denise Williams was "stunned" by the verdict and he vowed to appeal it.

"It's terrible, it's the wrong verdict on the facts," Way said. "But I think you have to respect what the jury does. Obviously I don't believe she's guilty of any of the three counts, I don't think anyone on the defense team does."

Iran eased some restrictions on its people and, for the first time in days, allowed them to make phone calls abroad via their mobile phones on Tuesday. It did not ease restrictions on the internet or permit texting services to be restored as the toll from days of bloody protests against the state rose to at least 646 people killed.

Although Iranians were able to call abroad, people outside the country could not call them, several people in the capital told The Associated Press.

The witnesses, who spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of reprisal, said SMS text messaging still was down and internet users inside Iran could not access anything abroad, although there were local connections to government-approved websites.

It was unclear if restrictions would ease further after authorities cut off all communications inside the country and to the outside world late Thursday.

Here is the latest:

This came a day after the European Parliament announced it would ban Iranian diplomats and representatives.

“Iran does not seek enmity with the EU, but will reciprocate any restriction,” Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi wrote on X on Tuesday.

He also criticized the European Parliament for not taking any significant action against Israel for the more than two-year war in Gaza that has killed more than 71,400 Palestinians, while banning Iranian diplomats after just “a few days of violent riots.”

Dutch Foreign Minister David van Weel said he summoned Iran’s ambassador to the Netherlands “to formally protest the excessive violence against peaceful protesters, large-scale arbitrary arrests, and internet shutdowns, calling for immediate restoration of internet access inside the Islamic Republic.

In a post on X, Weel also said the Dutch government supports EU sanctions against “human rights violators in Iran.”

The United Nations human rights chief is calling on Iranian authorities to immediately halt violence and repression against peaceful protesters, citing reports of hundreds killed and thousands arrested in a wave of demonstrations in recent weeks.

“The killing of peaceful demonstrators must stop, and the labelling of protesters as ‘terrorists’ to justify violence against them is unacceptable,” U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights Volker Türk said in a statement Tuesday.

Alluding to a wave of protests in Iran in 2022, Türk said demonstrators have sought “fundamental changes” to governance in the country, “and once again, the authorities’ reaction is to inflict brutal force to repress legitimate demands for change.”

“This cycle of horrific violence cannot continue,” he added.

It was also “extremely worrying” to hear some public statements from judicial officials mentioning the prospect of the use of the death penalty against protesters through expedited judicial proceedings, Türk said.

“Iranians have the right to demonstrate peacefully. Their grievances need to be heard and addressed, and not instrumentalized by anyone,” Türk said.

Finland’s foreign minister says she is summoning the Iranian ambassador after authorities in Tehran restricted internet access.

“Iran’s regime has shut down the internet to be able to kill and oppress in silence," Elina Valtonen wrote in a social media post Tuesday, adding, “this will not be tolerated. We stand with the people of Iran — women and men alike.”

Finland is “exploring measures to help restore freedom to the Iranian people” together with the European Union, Valtonen said.

Separately, Finnish police said they believe at least two people entered the courtyard of the Iranian embassy in Helsinki without permission Monday afternoon and tore down the Iranian flag. The embassy’s outer wall was also daubed with paint.

Iranian security forces arrested what a state television report described as terrorist groups linked to Israel in the southeastern city of Zahedan.

The report, without providing additional details, said the group entered through Iran’s eastern borders and carried U.S.-made guns and explosives that the group had planned to use in assassinations and acts of sabotage.

The Israeli military did not immediately comment on the allegations.

The Nobel Peace Prize laureate hailed people who have “long warned about this repression, at great personal risk.”

“The protests in Iran cannot be separated from the long-standing, state-imposed restrictions on girls’ and women’s autonomy, in all aspects of public life including education. Iranian girls, like girls everywhere, demand a life with dignity,” Yousafzai wrote on X.

“(Iran’s) future must be driven by the Iranian people, and include the leadership of Iranian women and girls — not external forces or oppressive regimes,” she added.

Yousafzai was awarded the peace prize in 2014 at the age of 17 for her fight for girls’ education in her home country, Pakistan. She is the youngest Nobel laureate.

The French Foreign Ministry said it has “reconfigured” its embassy in Tehran after reports that the facility's nonessential staff left Iran earlier this week.

The embassy's nonessential staff left the country Sunday and Monday, French news agency Agence France-Presse reported.

The ambassador remained on site and the embassy continued to function, the ministry said late Monday night.

Associated Press writer Angela Charlton contributed from Paris.

German Chancellor Friedrich Merz said he believes the Iranian government is in its “final days and weeks,” as he renewed a call for Iranian authorities to end violence against demonstrators immediately.

“If a regime can only keep itself in power by force, then it’s effectively at the end,” Merz said Tuesday during a visit to Bengaluru, India. “I believe we are now seeing the final days and weeks of this regime. In any case, it has no legitimacy through elections in the population. The population is now rising up against this regime.”

Merz said he hoped there is “a possibility to end this conflict peacefully," adding that Germany is in close contact with the U.S. and European governments.

The Israeli military said it continues to be “on alert for surprise scenarios” due to the ongoing protests in Iran, but has not made any changes to guidelines for civilians, as it does prior to a concrete threat.

“The protests in Iran are an internal matter,” Israeli military spokesperson Brig. Gen. Effie Defrin wrote on X.

Israel attacked Iran’s nuclear program over the summer, resulting in a 12-day war that killed nearly 1,200 Iranians and almost 30 Israelis. Over the past week, Iran has threatened to attack Israel if Israel or the U.S. attacks.

Mobile phones in Iran were able to call abroad Tuesday after a crackdown on nationwide protests in which the internet and international calls were cut. Several people in Tehran were able to call The Associated Press.

The AP bureau in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, was unable to call those numbers back.

Witnesses said the internet remained cut off from the outside world. Iran cut off the internet and calls on Thursday as protests intensified.

The U.S.-based Human Rights Activists News Agency, which has been accurate in previous unrest in recent years and gave the latest death toll early Tuesday. The agency relies on supporters in Iran to cross-check information.

The agency said 512 of the dead were protesters and 134 were security force members.

More than 10,700 people have been detained over the two weeks of protests, the agency said.

This frame grab from videos taken between Jan. 9 and Jan. 11, 2026, and circulating on social media purportedly shows images from a morgue with dozens of bodies and mourners after crackdownon the outskirts of Iran's capital, in Kahrizak, Tehran Province. (UGC via AP)

This frame grab from videos taken between Jan. 9 and Jan. 11, 2026, and circulating on social media purportedly shows images from a morgue with dozens of bodies and mourners after crackdown on the outskirts of Iran's capital, in Kahrizak, Tehran Province. (UGC via AP)

This frame grab from videos taken between Jan. 9 and Jan. 11, 2026, and circulating on social media purportedly shows images from a morgue with dozens of bodies and mourners after crackdown on the outskirts of Iran's capital, in Kahrizak, Tehran Province. (UGC via AP)

Protesters hold up placards and flags as they demonstrate outside the Iranian Embassy in London, Monday, Jan. 12, 2026. (AP Photo/Alastair Grant)

Shiite Muslims hold placards and chant slogans during a protest against the U.S. and show solidarity with Iran in Lahore, Pakistan, Sunday, Jan. 11, 2026. (AP Photo/K.M. Chaudary)

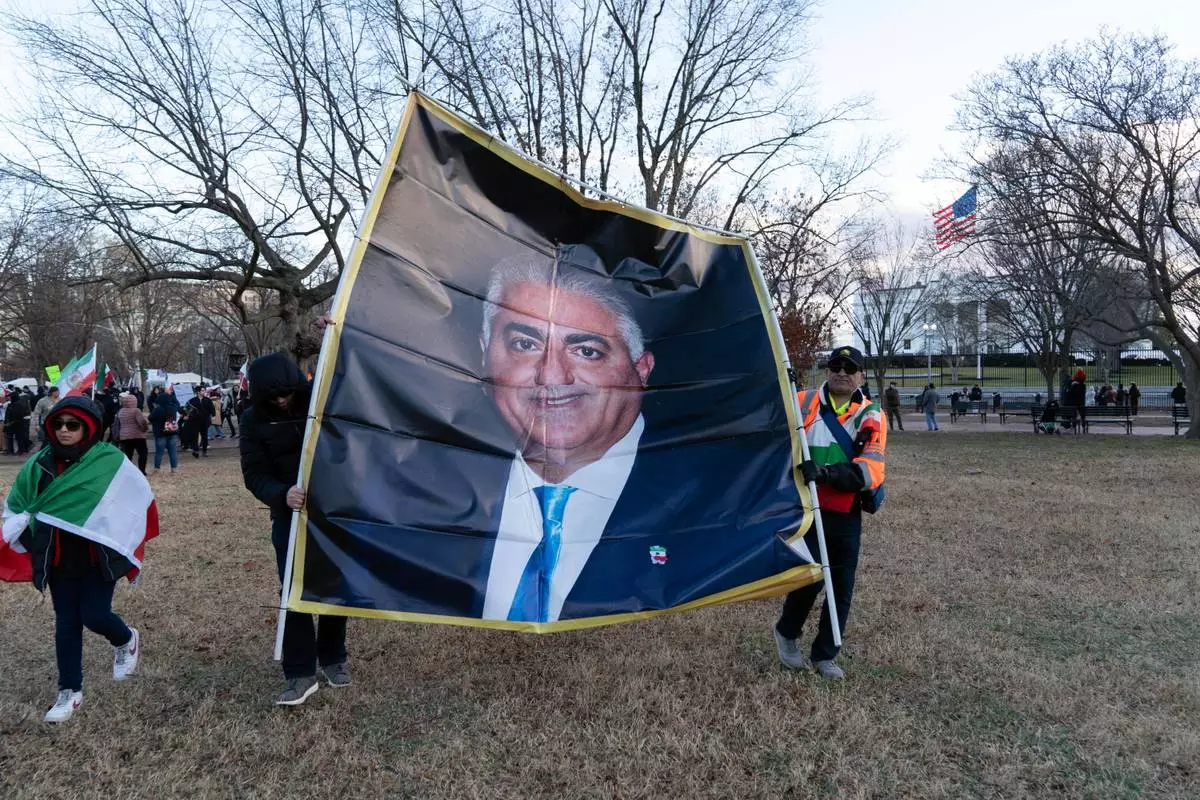

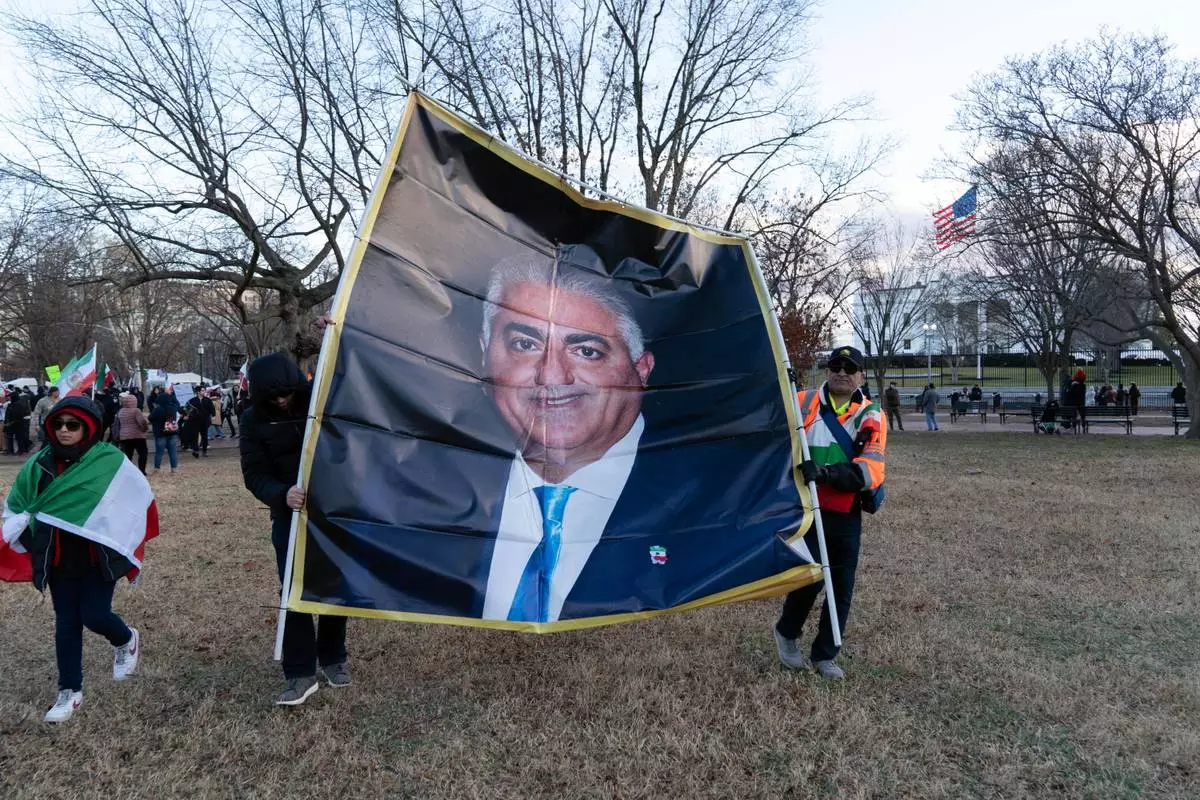

Activists carrying a photograph of Reza Pahlavi take part in a rally supporting protesters in Iran at Lafayette Park, across from the White House, in Washington, Sunday, Jan. 11, 2026. (AP Photo/Jose Luis Magana)

Protesters burn the Iranian national flag during a rally in support of the nationwide mass demonstrations in Iran against the government in Paris, Sunday, Jan. 11, 2026. (AP Photo/Michel Euler)

People attend a rally in Frankfurt, Germany, Monday, Jan. 12, 2026. (Boris Roessler/dpa via AP)

A picture of Ayatollah Ali Khamenei is set alight by protesters outside the Iranian Embassy in London, Monday, Jan. 12, 2026. (AP Photo/Alastair Grant)