Algeria's longtime leader Abdelaziz Bouteflika has been known as a wily political survivor ever since he fought for independence from France in the 1950s and 1960s. And his crafty concessions Monday aimed at quelling mass protests show he's not ready to give up yet.

While he abandoned his bid for a fifth term in office , his simultaneous postponement of an election set for next month has critics worried he intends to hold on to power indefinitely.

Click to Gallery

FILE - In this Dec. 14, 1973 file photo, the then Algerian Foreign Minister Abdelaziz Bouteflika, centre, looks on as U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, left, takes leave of President Houari Boumedienne of Algeria after talks in Algiers. Bouteflika became foreign minister at the young age of 25, and stood up to the likes of Henry Kissinger at the height of the Cold War, with the Algerian capital Algiers nicknamed "Moscow on the Med." (AP PhotoMichel Lipchitz, File)

FILE - In this April 11, 1999 file photo, Algerian presidential candidate and former Foreign Minister Abdelaziz Bouteflika waves to supporters as he campaigns in Algiers, Sunday, April 11, 1999. Algeria's longtime leader Abdelaziz Bouteflika has abandoned his bid for election to a fifth term in office, but has simultaneously postponed the election set for next month. (AP PhotoLaurent Rebours, File)

FILE - In this April 28, 2014 file photo, Algerian President Abdelaziz Bouteflika sits on a wheelchair after taking the oath as President, in Algiers. Algeria's longtime leader Bouteflika has abandoned his bid for election to a fifth term in office, but has simultaneously postponed the election set for next month.(AP PhotoSidali Djarboub, File)

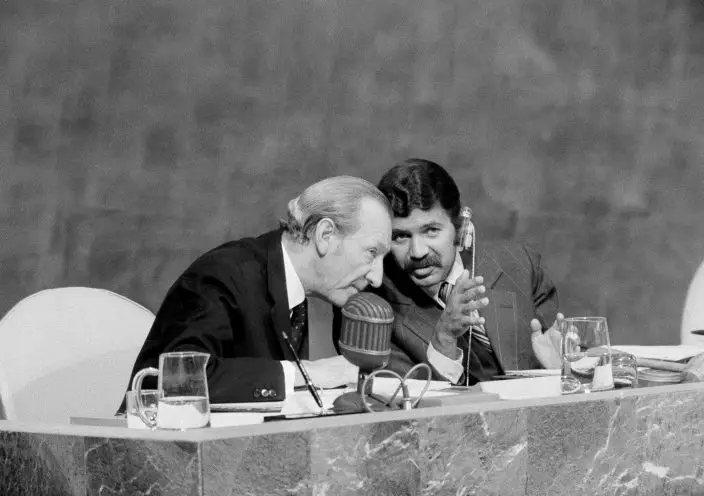

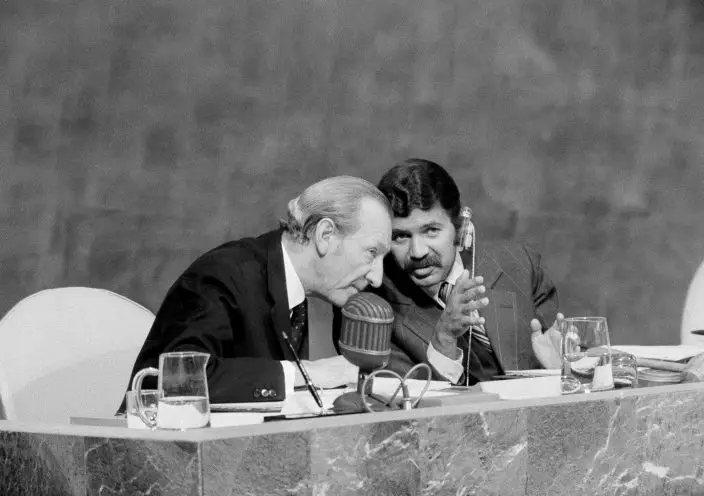

FILE - In this Sept. 18, 1974, President Abdelaziz Bouteflika of Algeria, right, and UN Secretary-General Kurt Waldheim confer during the opening of the General Assembly in New York. Algeria's longtime leader Abdelaziz Bouteflika has been known as a wily political survivor ever since he fought for independence from France in the 1960s, and now in 2019, he needs to overcome mass protests against his rule. (AP PhotoMarty Lederhandler, File)

FILE - In this May 4, 2017 file photo, Algerian President Abdelaziz Bouteflika's brothers Said Bouteflika, right, and Nacer Bouteflika talk before voting in Algiers. Said Bouteflika, 61, is a top aide to his brother Abdelaziz Bouteflika, and is said to hold enormous influence in the presidential apparatus, with critics claiming he has grown rich during Bouteflika’s presidency. (AP PhotoSidali Djarboub, File)

So much about the 82-year-old Bouteflika, badly weakened by a 2013 stroke, has remained an enigma. The president returned Sunday from two weeks in a Geneva hospital, but the exact state of his health is unclear.

FILE - In this Dec. 14, 1973 file photo, the then Algerian Foreign Minister Abdelaziz Bouteflika, centre, looks on as U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, left, takes leave of President Houari Boumedienne of Algeria after talks in Algiers. Bouteflika became foreign minister at the young age of 25, and stood up to the likes of Henry Kissinger at the height of the Cold War, with the Algerian capital Algiers nicknamed "Moscow on the Med." (AP PhotoMichel Lipchitz, File)

A slow, frail Bouteflika shown in rare televised images released on Monday night gave little hint of his firebrand past.

Bouteflika famously negotiated with the terrorist known as Carlos the Jackal to free oil ministers who had been taken hostage in a 1975 attack on OPEC headquarters in Vienna and flown to Algiers.

He became foreign minister at the young age of 25, and stood up to the likes of Henry Kissinger at the height of the Cold War. At the time, Algeria was a model of doctrinaire socialism tethered to the former Soviet Union and the country's capital, Algiers, was nicknamed "Moscow on the Med."

FILE - In this April 11, 1999 file photo, Algerian presidential candidate and former Foreign Minister Abdelaziz Bouteflika waves to supporters as he campaigns in Algiers, Sunday, April 11, 1999. Algeria's longtime leader Abdelaziz Bouteflika has abandoned his bid for election to a fifth term in office, but has simultaneously postponed the election set for next month. (AP PhotoLaurent Rebours, File)

More recently, Bouteflika helped reconcile his own citizens after a decade of civil war between radical Muslim militants and Algeria's security forces.

In 20 years as president, however, age and illness took its toll on the once-charismatic figure. Corruption scandals over infrastructure and hydrocarbon projects have also dogged him for years and tarnished many of his closest associates.

Secrecy surrounds Algeria's leadership and Bouteflika himself — it has never been clear whether full power lay in his hands, or whether army generals who molded the North African nation called the shots from offstage.

FILE - In this April 28, 2014 file photo, Algerian President Abdelaziz Bouteflika sits on a wheelchair after taking the oath as President, in Algiers. Algeria's longtime leader Bouteflika has abandoned his bid for election to a fifth term in office, but has simultaneously postponed the election set for next month.(AP PhotoSidali Djarboub, File)

All this has driven unprecedented protests that have shaken Algeria since last month, demanding Bouteflika abandon plans for a fifth term in the April 18 elections.

In a letter to the nation released by state news agency APS on Monday, Bouteflika stressed the importance of including Algeria's disillusioned youth in the reform process and putting the country "in the hands of new generations."

But for many of the protesters, the most important sentence said: "There will be no fifth term."

FILE - In this Sept. 18, 1974, President Abdelaziz Bouteflika of Algeria, right, and UN Secretary-General Kurt Waldheim confer during the opening of the General Assembly in New York. Algeria's longtime leader Abdelaziz Bouteflika has been known as a wily political survivor ever since he fought for independence from France in the 1960s, and now in 2019, he needs to overcome mass protests against his rule. (AP PhotoMarty Lederhandler, File)

Others were more cautious, as Bouteflika gave no date or timeline for the delayed election. Critics said they fear the moves could pave the way for the president to install a hand-picked successor. Others saw his decision to postpone the election indefinitely as a threat to democracy in Algeria.

Born in the border town of Oujda, Morocco, Bouteflika became one of his country's most enduring politicians. In Algeria's bloody independence war, he commanded the southern Mali front and slipped into France clandestinely in 1961 to contact jailed liberation leaders.

He later embodied the Third World revolutionary who defied the West, acting as a prominent voice for the developing nation's movement. He was active in the United Nations, and presided over the U.N. General Assembly in 1974.

FILE - In this May 4, 2017 file photo, Algerian President Abdelaziz Bouteflika's brothers Said Bouteflika, right, and Nacer Bouteflika talk before voting in Algiers. Said Bouteflika, 61, is a top aide to his brother Abdelaziz Bouteflika, and is said to hold enormous influence in the presidential apparatus, with critics claiming he has grown rich during Bouteflika’s presidency. (AP PhotoSidali Djarboub, File)

Yet Bouteflika stood firmly with the United States in the fight against terrorism after the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks, particularly on intelligence-sharing and military cooperation.

After becoming president in 1999, Bouteflika managed to bring stability to a country nearly brought to its knees in the 1990s as an Islamic insurgency left an estimated 200,000 people dead. He unveiled a bold program in 2005 to reconcile a nation fractured by a civil war by persuading Muslim radicals to lay down their arms. Many victims' families still oppose it.

Bouteflika and the country's armed forces neutralized Algeria's Islamic insurgency, but then watched it metastasize into a Sahara-wide movement linked to smuggling and kidnapping — and to al-Qaida.

He also failed to create an economy that could offer enough jobs for Algeria's growing youth population despite the nation's vast oil and gas wealth.

When Arab Spring uprisings in 2011 overthrew dictators to the east, Bouteflika balked at the region-wide calls for change. He then kept his job through a combination of swift salary and subsidy increases, a vigilant security force and taking advantage of the lack of unity among the country's opposition.

Concerns over Bouteflika's health began during his second term in 2005, when he secretly entered the Val de Grace military hospital in Paris for a bleeding ulcer. Numerous hospitalizations and medical visits followed, few publicly reported. In April 2013, he had a stroke.

Whole sections of Bouteflika's life have been kept secret, including his marital status — or how he was allowed to assume the presidency when the constitution demands that any head of state be wedded to an Algerian. There have been reports of a secret 1990 marriage to the daughter of a diplomat.

Said Bouteflika, 61, a brother of the president and top aide, is said to hold enormous influence in the presidential apparatus. Critics claim he is at the center of the circle of businessman, pejoratively called "oligarchs," who grew rich during Bouteflika's presidency.

After years in office, Bouteflika's powerful political machine had the constitution changed to cancel the presidency's two-term limit. He was then re-elected in 2009 and 2013, amid charges of fraud and a lack of powerful challengers.

The recent protests surprised Algeria's opaque leadership and freed the country's people, long fearful of a watchful security apparatus, to openly criticize the president. The citizens' revolt drew millions into the streets across the country to demand Bouteflika abandon his candidacy.

Associated Press writer Aomar Ouali in Algiers, Algeria, contributed to this report.

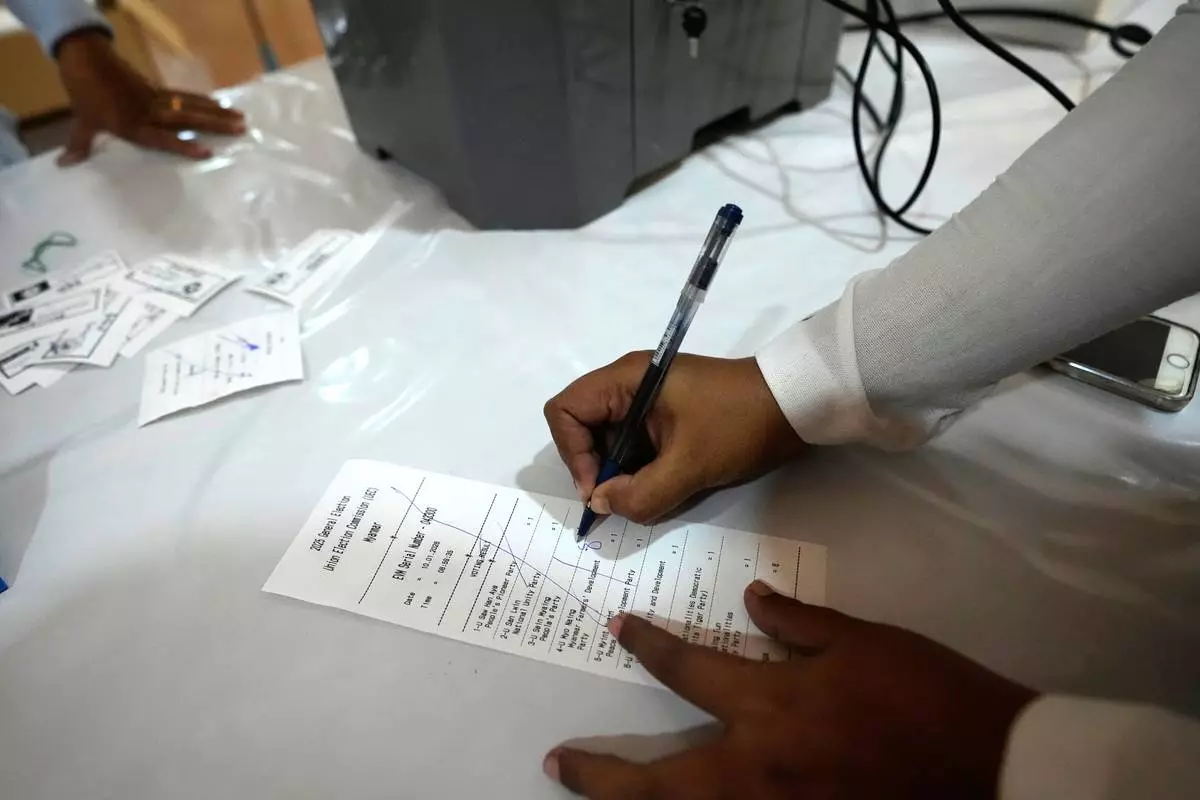

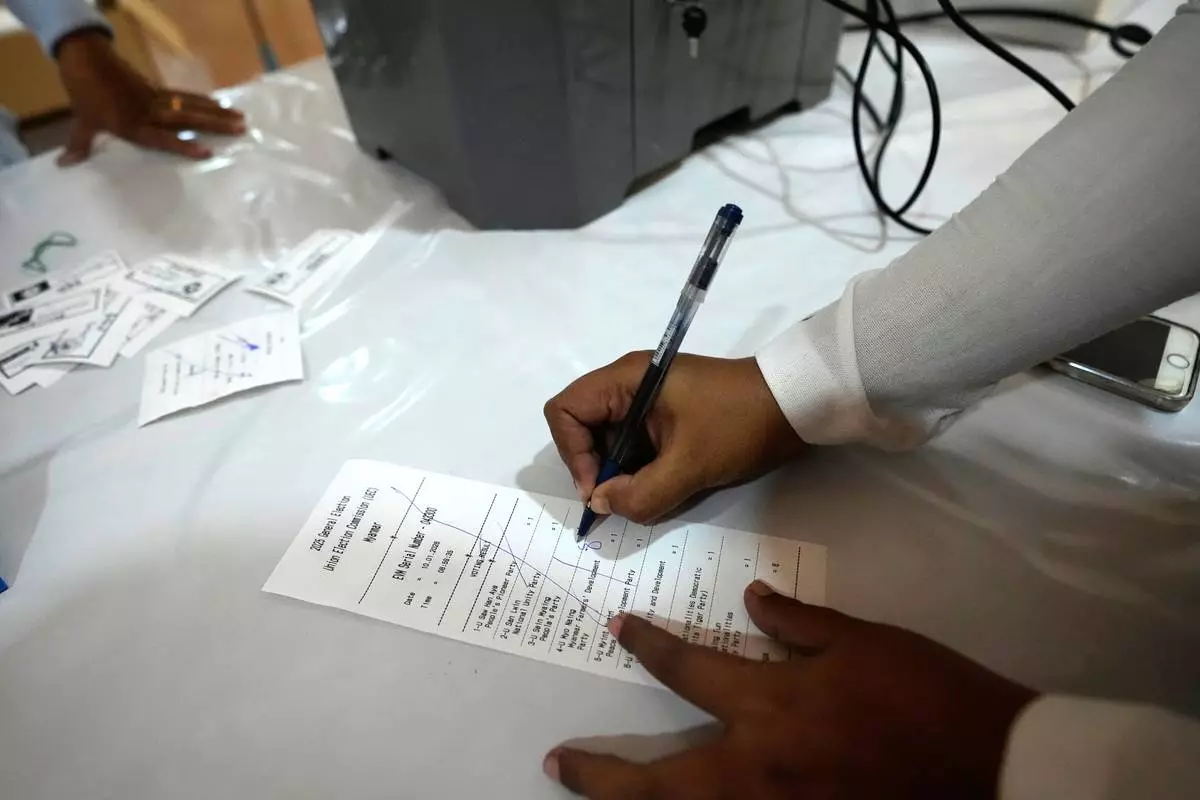

YANGON (AP) — Myanmar began a second round of voting Sunday in its first general election since a takeover that installed a military government five years ago.

Voting expanded to additional townships including some areas affected by the civil war between the military government and its armed opponents.

Polling stations opened at 6 a.m. local time in 100 townships across the country, including parts of Sagaing, Magway, Mandalay, Bago and Tanintharyi regions, as well as Mon, Shan, Kachin, Kayah and Kayin states. Many of those areas have recently seen clashes or remain under heightened security, underscoring the risks surrounding the vote.

The election is being held in three phases due to armed conflicts. The first round took place Dec. 28 in 102 of the country’s total 330 townships. A final round is scheduled for Jan. 25, though 65 townships will not take part because of fighting.

Myanmar has a two-house national legislature, totaling 664 seats. The party with a combined parliamentary majority can select the new president, who can name a Cabinet and form a new government. The military automatically receives 25% of seats in each house under the constitution.

Maj. Gen. Zaw Min Tun, the military government's spokesperson, told journalists on Sunday that the two houses of parliament will be convened in March, and the new government will take up its duties in April.

Critics say the polls organized by the military government are neither free nor fair and are an effort by the military to legitimize its rule after seizing power from the elected government of Aung San Suu Kyi in February 2021.

On Sunday, people in Yangon and Mandalay, the two largest cities in the country, were casting their ballots at high schools, government buildings and religious buildings.

At more than 10 polling stations visited by Associated Press journalists in Yangon and Mandalay, voter numbers ranged from about 150 at the busiest site to just a few at others, appearing lower than during the 2020 election when long lines were common.

The military government said there were more than 24 million eligible voters in the election, about 35% fewer than in 2020. The government called the turnout a success, claiming ballots were cast by more than 6 million people, about 52% of the more than 11 million eligible voters in the election's first phase.

Myo Aung, a chief minister of the Mandalay region, said more people turned out Sunday to vote than in the first phase.

“The weaknesses from Dec. 28 vote have been addressed, so I believe the Jan. 11 election to be well organized and successful,” he said.

Maung Maung Naing, who voted at a polling station in Mandalay’s Mahar Aung Myay township, said he wanted a government that will benefit the people.

“I only like a government that can make everything better for livelihoods and social welfare,” he said.

Sandar Min, an independent candidate from Yangon’s Latha township, said she decided to contest the election despite criticism because she wants to work with the government for the good of the country. She hopes the vote will bring change that reduces suffering.

“We want the country to be nonviolent. We do not accept violence as part of the change of the country,” Sandar Min said after casting a vote. “We care deeply about the people of this country.”

While more than 4,800 candidates from 57 parties are competing for seats in national and regional legislatures, only six parties are competing nationwide.

The first phase left the military-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party, or USDP, in a dominant position, winning nearly 90% of those contested seats in that phase in Pyithu Hluttaw, the lower house of parliament. It also won a majority of seats in regional legislatures.

Suu Kyi, Myanmar’s 80-year-old former leader, and her party aren’t participating in the polls. She is serving a 27-year prison term on charges widely viewed as spurious and politically motivated. Her party, the National League for Democracy, was dissolved in 2023 after refusing to register under new military rules.

Other parties also refused to register or declined to run under conditions they deem unfair, while opposition groups have called for a voter boycott.

Tom Andrews, a special rapporteur working with the U.N. human rights office, urged the international community Thursday to reject what he called a “sham election,” saying the first round exposed coercion, violence and political exclusion.

“You cannot have a free, fair or credible election when thousands of political prisoners are behind bars, credible opposition parties have been dissolved, journalists are muzzled, and fundamental freedoms are crushed,” Andrews said.

According to the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners, which keeps detailed tallies of arrests and casualties linked to the nation’s political conflicts, more than 22,000 people are detained for political offenses, and more than 7,600 civilians have been killed by security forces since 2021.

The army’s takeover triggered widespread peaceful protests that soon erupted into armed resistance, and the country slipped into a civil war.

A new Election Protection Law imposes harsh penalties and restrictions for virtually all public criticism of the polls. The authorities have charged more than 330 people under new electoral law for leafleting or online activity over the past few months.

Opposition organizations and ethnic armed groups had previously vowed to disrupt the electoral process.

On Sunday, attacks targeting polling stations and government buildings were reported in at least four of the 100 townships holding polls, with two administrative officials killed, independent online media, including Myanmar Now, reported.

A voter casts ballot at a polling station during the second phase of general election Sunday, Jan. 11, 2026, in Yangon, Myanmar. (AP Photo/Thein Zaw)

A voter casts ballot at a polling station during the second phase of general election in Mandalay, central Myanmar, Sunday, Jan. 11, 2026. (AP Photo/Aung Shine Oo)

A voter shows his finger, marked with ink to indicate he voted, at a polling station during the second phase of general election in Mandalay, central Myanmar, Sunday, Jan. 11, 2026. (AP Photo/Aung Shine Oo)

Sandar Min, an individual candidate for an election and former parliament member from ousted leader Aung San Suu Kyi's National League for Democracy (NLD) party, shows off her finger marked with ink indicating she voted at a polling station during the second phase of general election Sunday, Jan. 11, 2026, in Yangon, Myanmar. (AP Photo/Thein Zaw)

Voters wait for a polling station to open during the second phase of general election in Mandalay, central Myanmar, Sunday, Jan. 11, 2026. (AP Photo/Aung Shine Oo)

Buddhist monks walk past a polling station opened at a monastery one day before the second phase of the general election in Yangon, Myanmar, Saturday, Jan. 10, 2026. (AP Photo/Thein Zaw)

An official of the Union Election Commission checks a sample slip from an electronic voting machine as they prepare to set up a polling station opened at a monastery one day before the second phase of the general election in Yangon, Myanmar, Saturday, Jan. 10, 2026. (AP Photo/Thein Zaw)