The owner of J.Crew is filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, two months after the first person in New York tested positive for COVID-19.

The city, where J.Crew Group Inc. is based, went into lockdown soon after, followed by much the country. Retail stores in New York City and across the country shut their doors.

More bankruptcies across the retail sector are expected in coming weeks.

A window display at a J Crew store overlooks a quiet Rockefeller Center, Saturday, May 2, 2020, in New York. On April 30, the company announced it would apply for bankruptcy protection amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. (AP PhotoMark Lennihan)

J.Crew, already in trouble before the pandemic and laden with debt, and was acquired by TPG Capital and Leonard Green & Partners for $3 billion in 2011.

Operations at J.Crew will continue throughout a restructuring and clothing will still be available to purchase online.

The company said Monday that it anticipates its stores will reopen when it's safe to do so.

Retail veteran Mickey Drexler led J.Crew for more than a decade when it become a coveted fashion brand. But the chain appeared to lose its way at some point and Drexler severed his last ties with the company in January 2019.

There are a number of retail chains that were already teetering at the start of the year, but the pandemic is wreaking havoc equally across the entire sector. J.Crew is not the first to seek protection during the coronavirus outbreak, and no one expects it to be the last.

J.C. Penney and Neiman Marcus are expected to follow J.Crew. Jeans maker True Religion Apparel Inc. filed for bankruptcy protection last month.

Clothing store sales plummeted 50.5% in March, according to the latest Commerce Department report, and it has grown worse since.

In its last full year of operations, J.Crew generated $2.5 billion in sales, a 2% increase from the year before.

J.Crew had aimed to spin off its successful Madewell division as a public company and use the proceeds to pay down its debt. The company said Monday that Madewell will remain part of J.Crew Group Inc.

There were 193 J.Crew stores, 172 J.Crew Factory outlets and 132 Madewell locations as of Feb. 1.

SPRING CITY, Pa. (AP) — Tech companies and developers looking to plunge billions of dollars into ever-bigger data centers to power artificial intelligence and cloud computing are increasingly losing fights in communities where people don’t want to live next to them, or even near them.

Communities across the United States are reading about — and learning from — each other's battles against data center proposals that are fast multiplying in number and size to meet steep demand as developers branch out in search of faster connections to power sources.

In many cases, municipal boards are trying to figure out whether energy- and water-hungry data centers fit into their zoning framework. Some have entertained waivers or tried to write new ordinances. Some don’t have zoning.

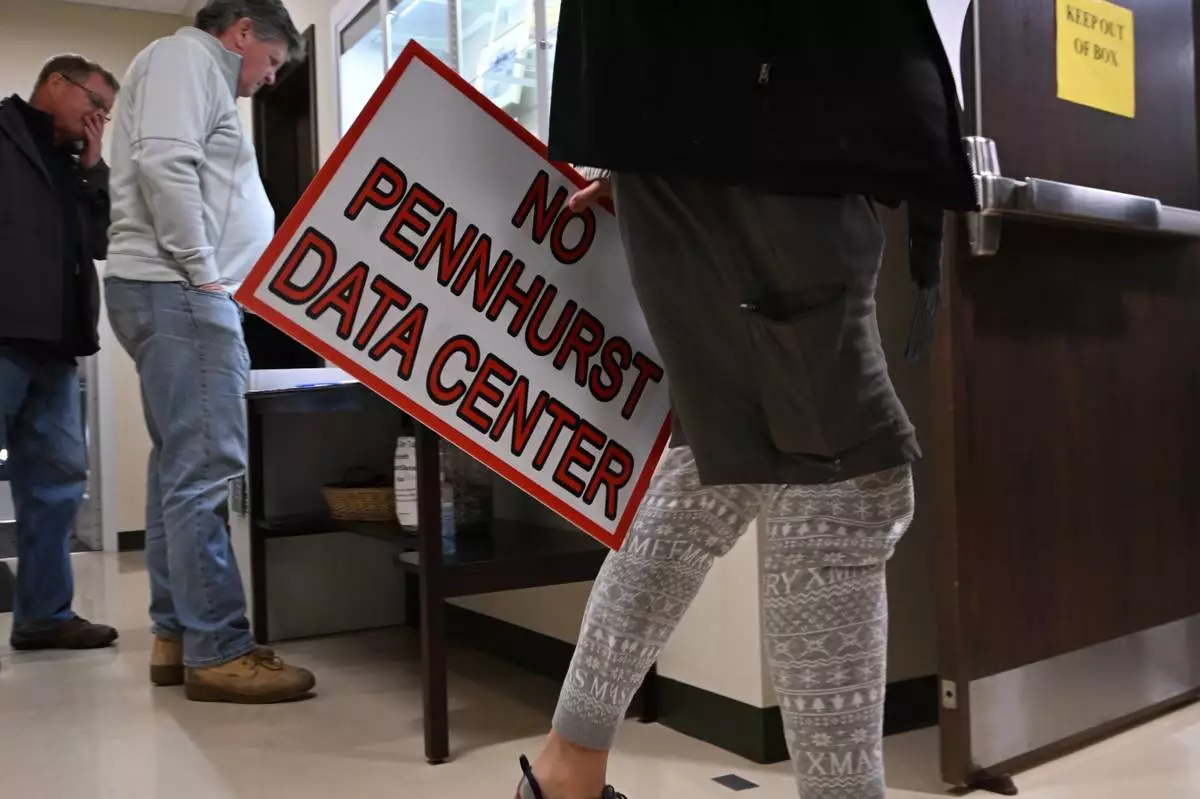

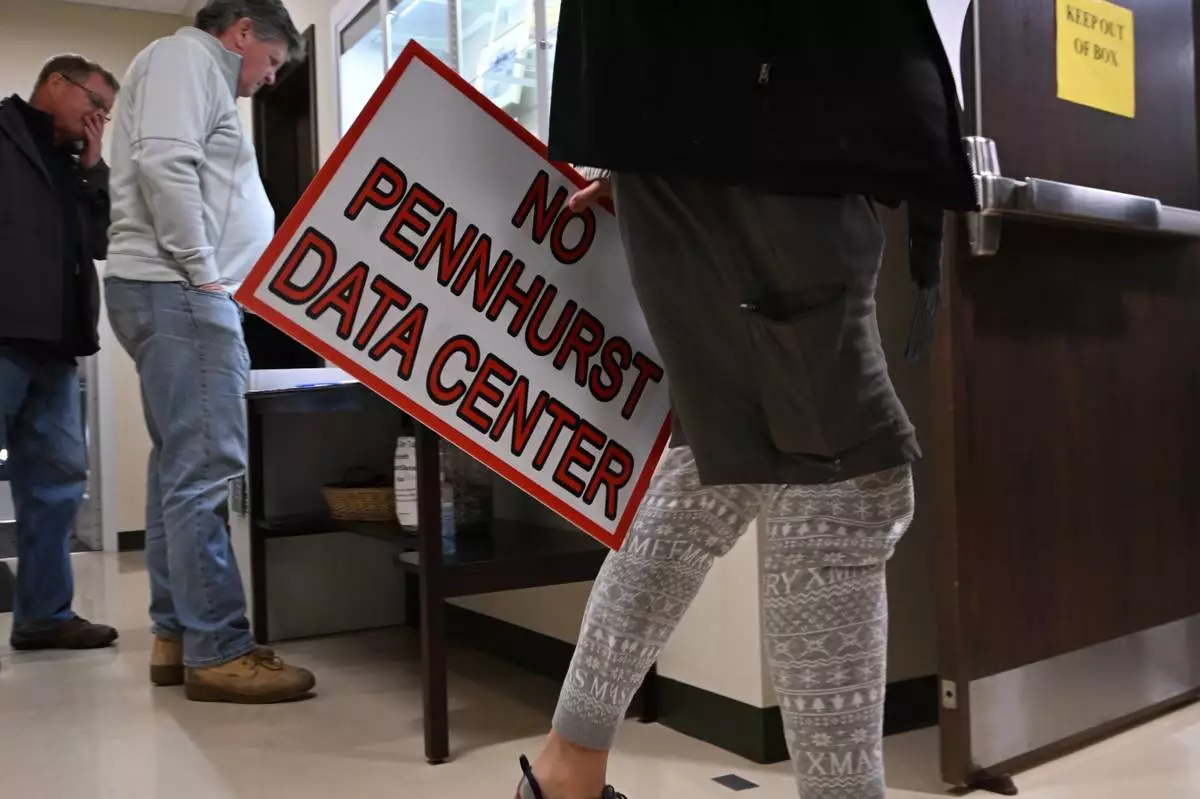

But as more people hear about a data center coming to their community, once-sleepy municipal board meetings in farming towns and growing suburbs now feature crowded rooms of angry residents pressuring local officials to reject the requests.

“Would you want this built in your backyard?” Larry Shank asked supervisors last month in Pennsylvania's East Vincent Township. “Because that’s where it’s literally going, is in my backyard.”

A growing number of proposals are going down in defeat, sounding alarms across the data center constellation of Big Tech firms, real estate developers, electric utilities, labor unions and more.

Andy Cvengros, who helps lead the data center practice at commercial real estate giant JLL, counted seven or eight deals he’d worked on in recent months that saw opponents going door-to-door, handing out shirts or putting signs in people’s yards.

“It’s becoming a huge problem,” Cvengros said.

Data Center Watch, a project of 10a Labs, an AI security consultancy, said it is seeing a sharp escalation in community, political and regulatory disruptions to data center development.

Between April and June alone, its latest reporting period, it counted 20 proposals valued at $98 billion in 11 states that were blocked or delayed amid local opposition and state-level pushback. That amounts to two-thirds of the projects it was tracking.

Some environmental and consumer advocacy groups say they’re fielding calls every day, and are working to educate communities on how to protect themselves.

“I’ve been doing this work for 16 years, worked on hundreds of campaigns I’d guess, and this by far is the biggest kind of local pushback I’ve ever seen here in Indiana,” said Bryce Gustafson of the Indianapolis-based Citizens Action Coalition.

In Indiana alone, Gustafson counted more than a dozen projects that lost rezoning petitions.

For some people angry over steep increases in electric bills, their patience is thin for data centers that could bring still-higher increases.

Losing open space, farmland, forest or rural character is a big concern. So is the damage to quality of life, property values or health by on-site diesel generators kicking on or the constant hum of servers. Others worry that wells and aquifers could run dry.

Lawsuits are flying — both ways — over whether local governments violated their own rules.

Big Tech firms Microsoft, Google, Amazon and Facebook — which are collectively spending hundreds of billions of dollars on data centers across the globe — didn’t answer Associated Press questions about the effect of community pushback.

Microsoft, however, has acknowledged the difficulties. In an October securities filing, it listed its operational risks as including “community opposition, local moratoriums, and hyper-local dissent that may impede or delay infrastructure development.”

Even with high-level support from state and federal governments, the pushback is having an impact.

Maxx Kossof, vice president of investment at Chicago-based developer The Missner Group, said developers worried about losing a zoning fight are considering selling properties once they secure a power source — a highly sought-after commodity that makes a proposal far more viable and valuable.

“You might as well take chips off the table,” Kossof said. “The thing is you could have power to a site and it’s futile because you might not get the zoning. You might not get the community support.”

Some in the industry are frustrated, saying opponents are spreading falsehoods about data centers — such as polluting water and air — and are difficult to overcome.

Still, data center allies say they are urging developers to engage with the public earlier in the process, emphasize economic benefits, sow good will by supporting community initiatives and talk up efforts to conserve water and power and protect ratepayers.

“It's definitely a discussion that the industry is having internally about, ‘Hey, how do we do a better job of community engagement?’” said Dan Diorio of the Data Center Coalition, a trade association that includes Big Tech firms and developers.

Winning over local officials, however, hasn't translated to winning over residents.

Developers pulled a project off an October agenda in the Charlotte suburb of Matthews, North Carolina, after Mayor John Higdon said he informed them it faced unanimous defeat.

The project would have funded half the city’s budget and developers promised environmentally friendly features. But town meetings overflowed, and emails, texts and phone calls were overwhelmingly opposed, “999 to one against,” Higdon said.

Had council approved it, “every person that voted for it would no longer be in office,” the mayor said. “That's for sure.”

In Hermantown, a suburb of Duluth, Minnesota, a proposed data center campus several times larger than the Mall of America is on hold amid challenges over whether the city’s environmental review was adequate.

Residents found each other through social media and, from there, learned to organize, protest, door-knock and get their message out.

They say they felt betrayed and lied to when they discovered that state, county, city and utility officials knew about the proposal for an entire year before the city — responding to a public records request filed by the Minnesota Center for Environmental Advocacy — released internal emails that confirmed it.

“It’s the secrecy. The secrecy just drives people crazy,” said Jonathan Thornton, a realtor who lives across a road from the site.

Documents revealing the extent of the project emerged days before a city rezoning vote in October. Mortenson, which is developing it for a Fortune 50 company that it hasn't named, says it is considering changes based on public feedback and that “more engagement with the community is appropriate."

Rebecca Gramdorf found out about it from a Duluth newspaper article, and immediately worried that it would spell the end of her six-acre vegetable farm.

She found other opponents online, ordered 100 yard signs and prepared for a struggle.

“I don’t think this fight is over at all,” Gramdorf said.

Follow Marc Levy on X at https://x.com/timelywriter.

People sign in and head into an East Vincent Township supervisors meeting where an agenda item involved a data center proposal at the former Pennhurst state hospital grounds, Dec. 17, 2025, in Spring City, Pa. (AP Photo/Marc Levy)

Mike Petak of Spring City gestures while speaking to East Vincent Township supervisors in opposition to a data center proposal at the former Pennhurst state hospital grounds, Dec. 17, 2025, in Spring City, Pa. (AP Photo/Marc Levy)