Fitness junkies locked out of gyms, commuters fearful of public transit, and families going stir crazy inside their homes during the coronavirus pandemic have created a boom in bicycle sales unseen in decades.

In the United States, bicycle aisles at mass merchandisers like Walmart and Target have been swept clean, and independent shops are doing a brisk business and are selling out of affordable “family” bikes.

Click to Gallery

FILE-In this May 20, 2020 photo, a bicyclist wears a pandemic mask while riding in Portland, Maine. A bicycle rush kicked off mid-March around the time countries were shutting their borders, businesses were closing and stay-at-home orders were being imposed because of the coronavirus pandemic in which millions have been infected and nearly 400,000 have died. (AP PhotoRobert F. Bukaty)

FILE-In this Wednesday, April 8, 2020, photo, bicyclists wear pandemic masks while riding in Portland, Maine. Bicycle sales have surged as shut-in families try to find a way to keep kids active at a time of lockdowns and stay-at-home orders during the coronavirus pandemic. (AP PhotoRobert F. Bukaty)

FILE-In this Thursday, June 11, 2020, photo, bicycle display racks are empty at a Target in Milford, Mass. A bicycle rush has been brought on by the coronavirus pandemic. In the U.S., bicycle aisles at mass merchandisers like Walmart and Target have been swept clean, officials say, and independent shops are doing a brisk business and are selling out of low- to mid-range "family" bikes. (AP PhotoRobert F. Bukaty)

FILE-In this Tuesday, June 9, 2020 photo, bike display racks are empty at a Walmart in Falmouth, Maine. A bicycle rush has been brought on by the coronavirus pandemic. In the U.S., bicycle aisles at mass merchandisers like Walmart and Target have been swept clean, officials say, and independent shops are doing a brisk business and are selling out of low- to mid-range "family" bikes. (AP PhotoDavid Sharp)

Bicycle sales over the past two months saw their biggest spike in the U.S. since the oil crisis of the 1970s, said Jay Townley, who analyzes cycling industry trends at Human Powered Solutions.

FILE-In this May 20, 2020 photo, a bicyclist wears a pandemic mask while riding in Portland, Maine. A bicycle rush kicked off mid-March around the time countries were shutting their borders, businesses were closing and stay-at-home orders were being imposed because of the coronavirus pandemic in which millions have been infected and nearly 400,000 have died. (AP PhotoRobert F. Bukaty)

“People quite frankly have panicked, and they’re buying bikes like toilet paper,” Townley said, referring to the rush to buy essentials like toilet paper and hand sanitizer that stores saw at the beginning of the pandemic.

The trend is mirrored around the globe, as cities better known for car-clogged streets, like Manila and Rome, install bike lanes to accommodate surging interest in cycling while public transport remains curtailed. In London, municipal authorities plan to go further by banning cars from some central thoroughfares.

Bike shop owners in the Philippine capital say demand is stronger than at Christmas. Financial incentives are boosting sales in Italy, where the government’s post-lockdown stimulus last month included a 500-euro ($575) “bici bonus” rebate for up to 60% of the cost of a bike.

FILE-In this Wednesday, April 8, 2020, photo, bicyclists wear pandemic masks while riding in Portland, Maine. Bicycle sales have surged as shut-in families try to find a way to keep kids active at a time of lockdowns and stay-at-home orders during the coronavirus pandemic. (AP PhotoRobert F. Bukaty)

But that's if you can get your hands on one. The craze has led to shortages that will take some weeks, maybe months, to resolve, particularly in the U.S., which relies on China for about 90% of its bicycles, Townley said. Production there was largely shut down due to the coronavirus and is just resuming.

The bicycle rush kicked off in mid-March around the time countries were shutting their borders, businesses were closing, and stay-at-home orders were being imposed to slow the spread of the coronavirus that has infected millions of people and killed more than 450,000.

Sales of adult leisure bikes tripled in April while overall U.S. bike sales, including kids’ and electric-assist bicycles, doubled from the year before, according to market research firm NPD Group, which tracks retail bike sales.

FILE-In this Thursday, June 11, 2020, photo, bicycle display racks are empty at a Target in Milford, Mass. A bicycle rush has been brought on by the coronavirus pandemic. In the U.S., bicycle aisles at mass merchandisers like Walmart and Target have been swept clean, officials say, and independent shops are doing a brisk business and are selling out of low- to mid-range "family" bikes. (AP PhotoRobert F. Bukaty)

It's a far cry from what was anticipated in the U.S. The $6 billion industry had projected lower sales based on lower volume in 2019 in which punitive tariffs on bicycles produced in China reached 25%.

There are multiple reasons for the pandemic bicycle boom.

Around the world, many workers were looking for an alternative to buses and subways. People unable to go to their gyms looked for another way to exercise. And shut-in families scrambled to find a way to keep kids active during stay-at-home orders.

FILE-In this Tuesday, June 9, 2020 photo, bike display racks are empty at a Walmart in Falmouth, Maine. A bicycle rush has been brought on by the coronavirus pandemic. In the U.S., bicycle aisles at mass merchandisers like Walmart and Target have been swept clean, officials say, and independent shops are doing a brisk business and are selling out of low- to mid-range "family" bikes. (AP PhotoDavid Sharp)

“Kids are looking for something to do. They’ve probably reached the end of the internet by now, so you’ve got to get out and do something,” said Dave Palese at Gorham Bike and Ski, a Maine shop where there are slim pickings for family-oriented, leisure bikes.

Bar Harbor restaurateur Brian Smith bought a new bike for one of his daughters, a competitive swimmer, who was unable to get into the pool. On a recent day, he was heading back to his local bike shop to outfit his youngest daughter, who’d just learned how to ride.

His three daughters use their bikes every day, and the entire family goes for rides a couple of times a week. The fact that they’re getting exercise and enjoying fresh air is a bonus.

“It’s fun. Maybe that’s the bottom line. It’s really fun to ride bikes,” Smith said as he and his 7-year-old daughter, Ellery, pedaled to the bicycle shop.

The pandemic is also driving a boom in electric-assist bikes, called e-bikes, which were a niche part of the overall market until now. Most e-bikes require a cyclist to pedal, but electric motors provide extra oomph.

VanMoof, a Dutch e-bike maker, is seeing “unlimited demand” since the pandemic began, resulting in a 10-week order backlog for its commuter electric bikes, compared with typical one-day delivery time, said co-founder Taco Carlier.

The company's sales surged 138% in the U.S. and rocketed 184% in Britain in the February-April period over last year, with big gains in other European countries. The company is scrambling to ramp up production as fast as it can, but it will take two to three months to meet the demand, Carlier said.

“We did have some issues with our supply chain back in January, February when the crisis hit first in Asia,” said Carlier. But “the issue is now with demand, not supply.”

Sales at Cowboy, a Belgian e-bike maker, tripled in the January-April period from last year. Notably, they spiked in Britain and France at around the same time in May that those countries started easing lockdown restrictions, said Chief Marketing Officer Benoit Simeray.

“It’s now becoming very obvious for most of us living in and around cities that we don’t want to go back into public transportation,” said Simeray. But people may still need to buy groceries or commute to the office one or two days a week, so “then they’re starting to really, really think about electric bikes as the only solution they’ve got.”

In Maine, Kate Worcester, a physician’s assistant, bought e-bikes for herself and her 12-year-old son so they could have fun at a time when she couldn’t travel far from the hospital where she worked.

Every night, she and her son ride 20 miles or 30 miles (30 or 50 kilometers) around Acadia National Park.

“It’s by far the best fun I’ve had with him,” she said. “That’s been the biggest silver lining in this terrible pandemic — to be able to leave work and still do an activity and talk and enjoy each other.”

Joe Minutolo, co-owner of Bar Harbor Bicycle Shop, said he hopes the sales surge translates into long-term change.

“People are having a chance to rethink things,” he said. “Maybe we’ll all learn something out of this, and something really good will happen.”

DALLAS (AP) — Longtime Sen. John Cornyn and MAGA favorite Ken Paxton are heading to a May runoff in Texas’ Republican Senate primary, setting up what's expected to be a nasty and expensive second round and a renewed push to win the endorsement of President Donald Trump.

On the Democratic side, Congresswoman Jasmine Crockett and state Rep. James Talarico were competing for their party's nomination and the right to face the winner of the Cornyn-Paxton runoff in November.

Texas, along with North Carolina and Arkansas, kicked off midterm elections with control of Congress at stake and against the backdrop of the U.S.-Israeli war with Iran.

Cornyn is seeking a fifth term but facing a tough challenge from Paxton, the state attorney general. He hopes to avoid becoming the first Republican senator in Texas history to seek reelection and not be renominated.

The GOP contest also featured U.S. Rep. Wesley Hunt, who finished a distant third and conceded. But him making it a three-way race made it tougher for any candidate to reach the 50% vote threshold needed to win the nomination outright and avoid the May 26 runoff.

All three campaigned on their ties to Trump, who did not make an endorsement in the race. Now both Cornyn and Paxton will again fiercely compete to curry the president's favor.

Cornyn was facing a tough enough battle that he didn't hold an election night party. Instead, in comments to reporters in Austin, he sought to make the case that a runoff win by Paxton would leave “a dead weight at the top of the ticket for Republicans.”

“I’ve worked for decades to build the Republican Party, both here in Texas and nationally,” Cornyn said. “I refuse to allow a flawed, self-centered and shameless candidate like Ken Paxton to risk everything we’ve worked so hard to build over these many years.”

Addressing supporters in Dallas, Paxton made a point of saying he felt like he had during a recent trip to Mar-a-Lago, Trump’s Florida estate. He also proclaimed: “We proved something they’ll never understand in Washington.”

“Texas is not for sale,” he said.

Cornyn’s cool relationship with Trump is part of what made him vulnerable. He and allied groups spent at least $64 million in television advertising alone since July to try stabilize his support.

Paxton, who began campaigning in earnest only last month, has made national headlines for filing lawsuits against Democratic initiatives. He remained popular in Texas despite a 2023 impeachment trial on corruption charges, of which he was acquitted, and accusations of marital infidelity by his wife.

Senate GOP leaders, who are backing Cornyn, worry that Paxton’s liabilities would make it harder to defend the seat if he is the nominee — and require significant spending that could be better used elsewhere.

In the Democratic campaign, Crockett and Talarico each argued that they would be the stronger general election candidate in a state that backed Trump by almost 14 percentage points in 2024 and where no Democrat has won a statewide race in over 30 years.

Voting was extended in Dallas County and Williamson County, outside Austin, after voters reported being turned away and directed to different voting precincts because of new primary rules. Paxton’s office later challenged a decision keeping the polls open longer, and the state Supreme Court ruled that ballots cast by people not in line by 7 p.m. should be separated from others.

It was not immediately clear how the court’s action would be carried out or how many eligible ballots remained to be counted in Dallas County, Crockett’s home base. Crockett, meanwhile, planned to file a lawsuit after voting was concluded.

Crockett and Talarico waged a spirited race as Democrats look for their first Senate win in Texas since 1988.

Talarico, a seminarian who often references the Bible, held rallies across the state including in heavily Republican areas. Crockett has built a national profile for zinger attacks on Republicans and focused on turning out Black voters in the Dallas and Houston areas.

Dallas voter Tanu Sani said she cast her ballot for Talarico because he “really spoke to me in the way he tries to unify.”

Tomas Sanchez, a voter in Dallas County, said he supported Crockett because “she cares about immigrants, she cares about the American people in a way that a lot of the Republicans have proven they haven’t.”

Talarico outspent Crockett on television advertising by more than four to one as of late February. He got a burst of attention — and campaign contributions — last month from CBS' decision not to air his interview with late-night host Stephen Colbert, who said the network pulled the interview for fear of angering Trump's FCC.

Texas’ races also featured new congressional district boundaries that GOP lawmakers — urged on by Trump — redrew to help elect more Republicans. The result matched several Democratic incumbents in primary fights and set up new general election battlegrounds.

In the 34th District, former Rep. Mayra Flores was attempting a comeback but was defeated by Eric Flores, a lawyer endorsed by Trump, for the nomination to run against Democratic Rep. Vicente Gonzalez. Mayra Flores made history in a 2022 special election as the first Republican to win in the Rio Grande Valley in 150 years but lost her bid for a full term later that year.

In the 23rd District, Rep. Tony Gonzales is considered vulnerable after an alleged affair with a staffer who killed herself. He faced a challenge from gun manufacturer and YouTube influencer Brandon Herrera, who calls himself “the AK guy.” The district includes Uvalde, site of a deadly 2022 shooting at Robb Elementary School.

Republican Rep. Dan Crenshaw was challenged in the 2nd District by state Rep. Steve Toth, who was endorsed by Sen. Ted Cruz.

Former Major League Baseball star Mark Teixeira clinched the Republican primary to succeed GOP Chip Roy in southwest Texas’ 21st District.

Democrat Bobby Pulido, a Latin Grammy winner, won his party's primary in South Texas' 15th District against physician Ada Cuellar. Pulido will face two-term Republican Rep. Monica De La Cruz.

In the 33rd District, Democratic Rep. Julie Johnson faced former Rep. Colin Allred, a former NFL linebacker and 2024 Senate nominee.

Democratic Rep. Al Green was fighting to stay in office after his Houston-based 9th District was drawn to be lean Republican. Green, 78, ran in a newly drawn 18th District against Democratic Rep. Christian Menefee, 37, who won a January special election for the current 18th District.

Republican Gov. Greg Abbott easily won his primary and will face Democratic state Rep. Gina Hinojosa. Roy advanced to a primary runoff with Mayes Middleton for attorney general.

Weissert reported from Washington. Associated Press writers Sara Cline and Jamie Stengle in Dallas and Bill Barrow in Atlanta contributed.

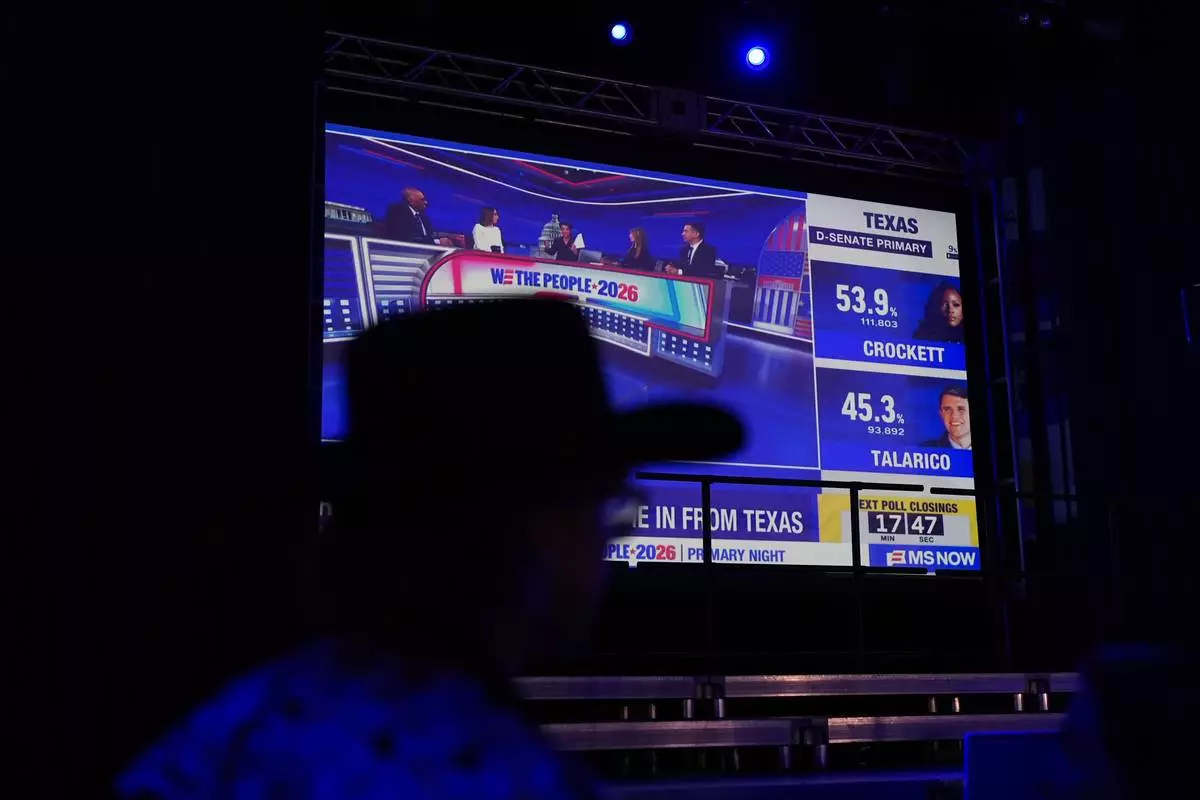

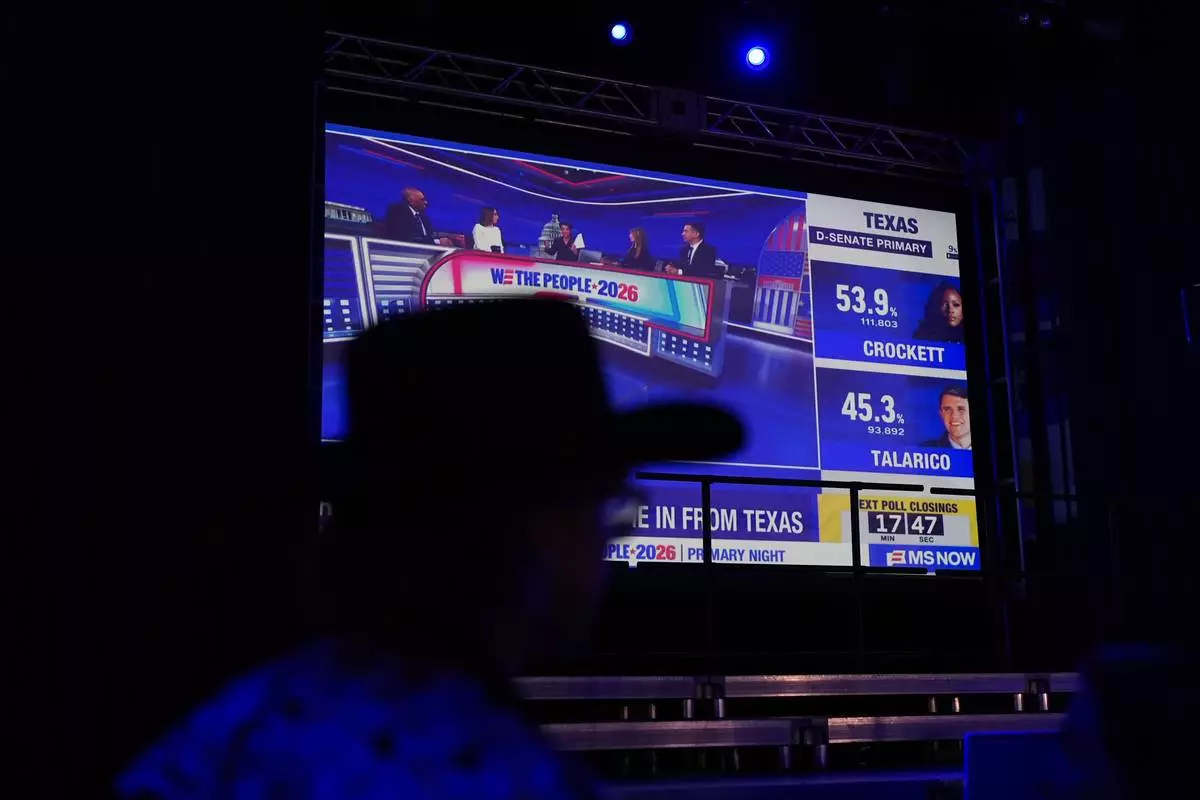

Supporters of Texas state Rep. James Talarico, D-Austin, a Democratic candidate for the U.S. Senate, react as results come in during a primary election watch party Tuesday, March 3, 2026, in Austin, Texas. (AP Photo/Eric Gay)

Rep. Jasmine Crockett, D-Texas, a Democratic candidate for U.S. Senate, speaks during a primary election watch party Tuesday, March 3, 2026, in Dallas. (AP Photo/Tony Gutierrez)

Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton, a Republican candidate for the U.S. Senate, poses for a selfie with a supporter during a primary election night watch party Tuesday, March 3, 2026, in Dallas. (AP Photo/Julio Cortez)

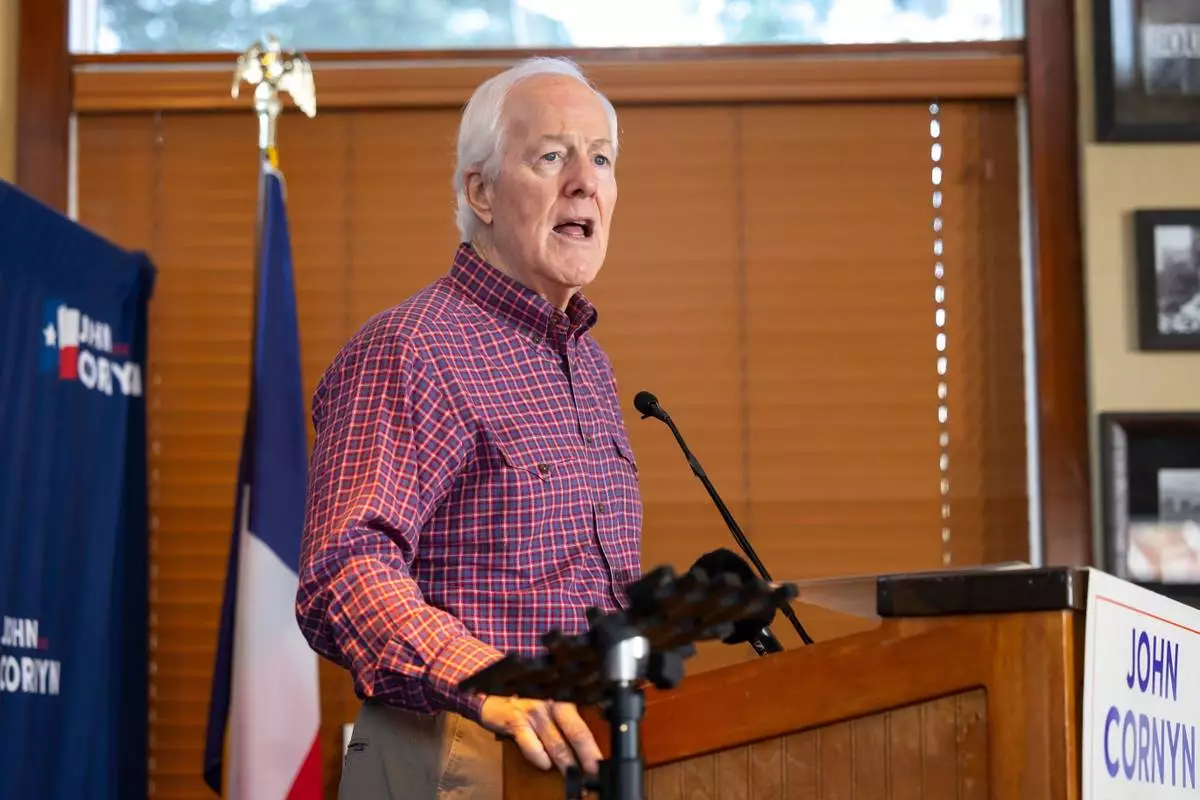

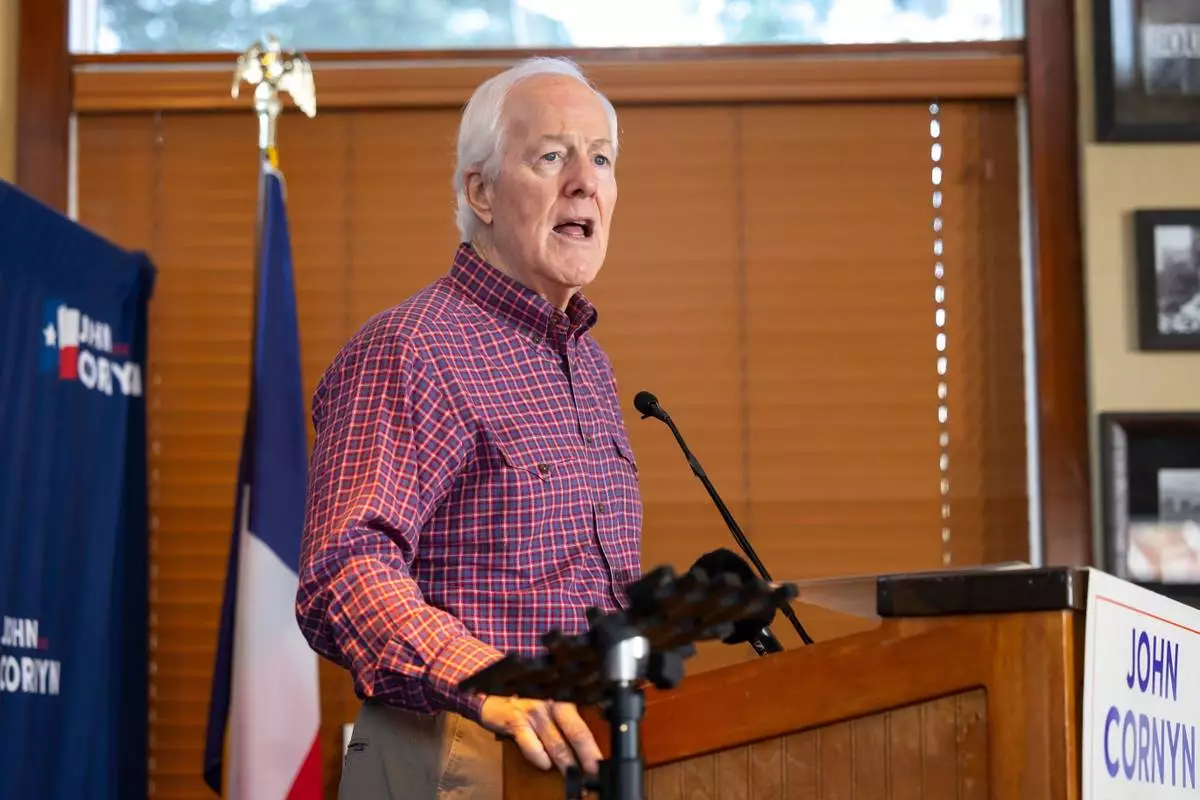

Sen. John Cornyn, R-Texas, speaks to the media Tuesday, March 3, 2026, in Austin, Texas. (AP Photo/Jack Myer)

A supporter of Texas state Rep. James Talarico, D-Austin, a Democratic candidate for the U.S. Senate, watches as results come in during a primary election night watch party Tuesday, March 3, 2026, in Austin, Texas. (AP Photo/Eric Gay)

Supporters of Rep. Jasmine Crockett, D-Texas, a Democratic candidate for U.S. Senate, arrive for a primary election night watch party Tuesday, March 3, 2026, in Dallas. (AP Photo/Tony Gutierrez)

A supporter of Texas state Rep. James Talarico, D-Austin, a Democratic candidate for the U.S. Senate, wears a Texas state flag in their hat during a primary election watch party Tuesday, March 3, 2026, in Austin, Texas. (AP Photo/Eric Gay)

U.S. Reps. Adelita Grijalva of Arizona, Jasmine Crockett of Texas and Ayanna Pressley of Massachusetts, speak with voters during primary election day at the West Gray Metropolitan Multi-Service Center in Houston on Tuesday, March 3, 2026. (Raquel Natalicchio /Houston Chronicle via AP)

James Talarico, a Texas Democratic primary candidate for U.S. Senate, speaks during an event at the University of Houston Monday, March 2, 2026, in Houston. (AP Photo/Ashley Landis)

Primary candidate for U.S. Senate Rep. Jasmine Crockett, D-Texas, responds to a question during a broadcast interview at a campaign stop in Dallas, Friday, Feb. 27, 2026. (AP Photo/Tony Gutierrez)

Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton, a Republican candidate for the U.S. Senate, addresses supporters during a campaign stop, Monday, March 2, 2026, in Waco, Texas. (AP Photo/Tony Gutierrez)

Sen. John Cornyn, R-Texas, speaks during a campaign stop in The Woodlands, Texas, Saturday, Feb. 28, 2026. (AP Photo/Annie Mulligan)