PHILADELPHIA (AP) — Fifty years ago, Philadelphia prison officials ended a medical testing program that had allowed an Ivy League researcher to conduct human testing on incarcerated people, many of them Black, for decades. Now, survivors of the program and their descendants want reparations.

Thousands of people at Holmesburg Prison were exposed to painful skin tests, anesthesia-free surgery, harmful radiation and mind-altering drugs for research on everything from hair dye, detergent and other household goods to chemical warfare agents and dioxins. In exchange, they might receive $1-a-day in pocket change they used to buy commissary items or try to make bail.

Click to Gallery

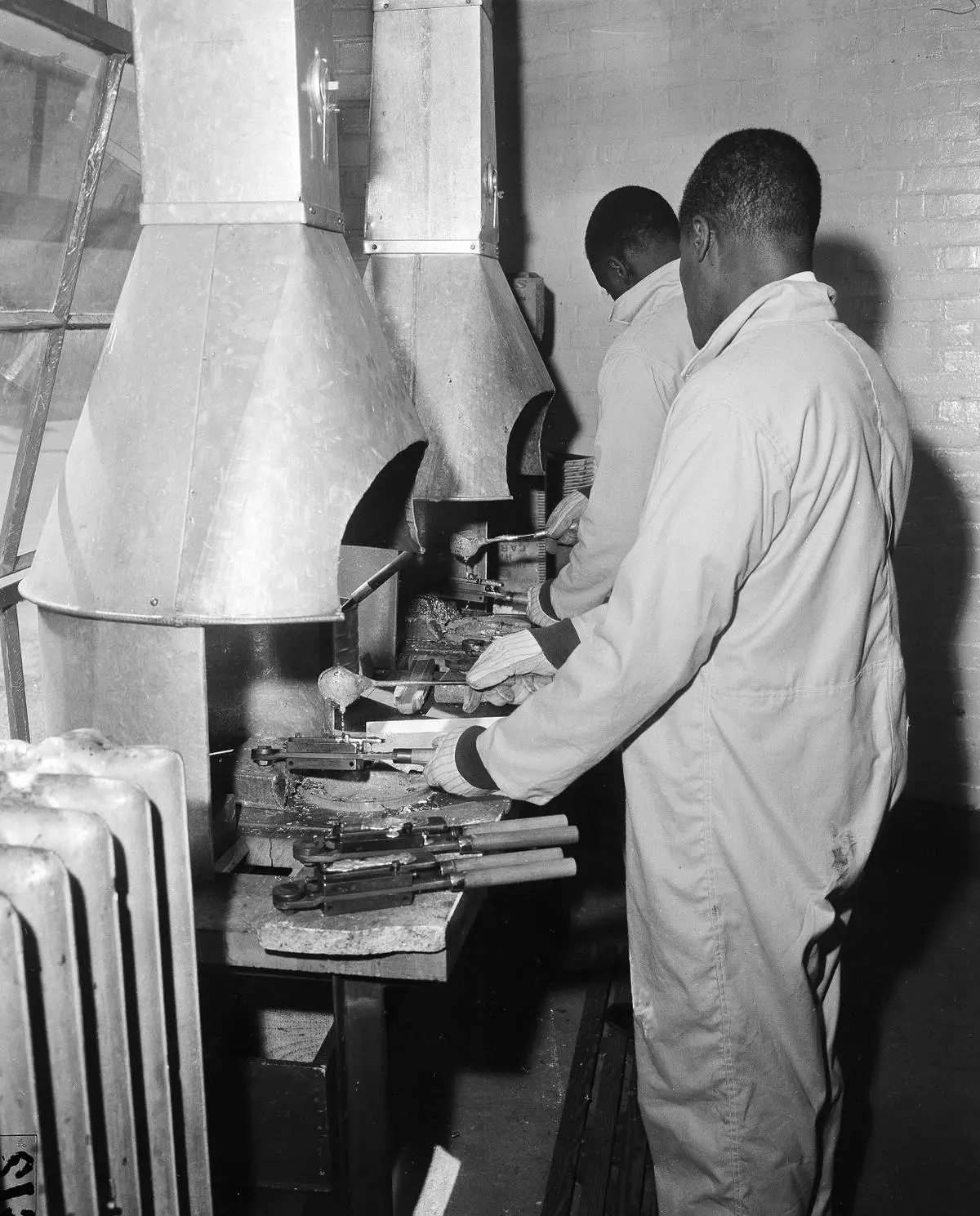

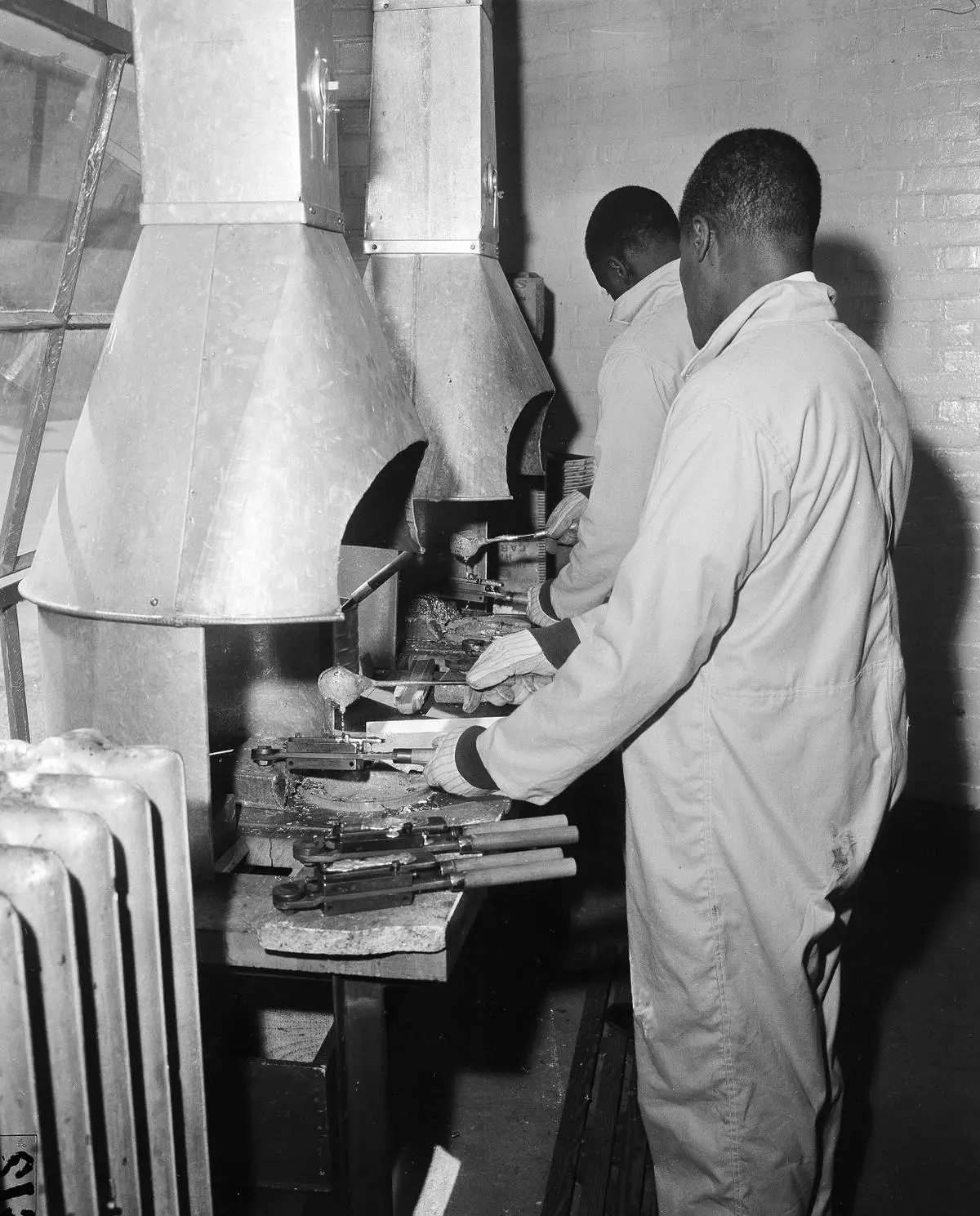

FILE - People incarcerated at the maximum security Holmesburg Prison in Philadelphia, turn out bullets for police revolvers, April 16, 1957. (AP Photo/Bill Ingraham, File)

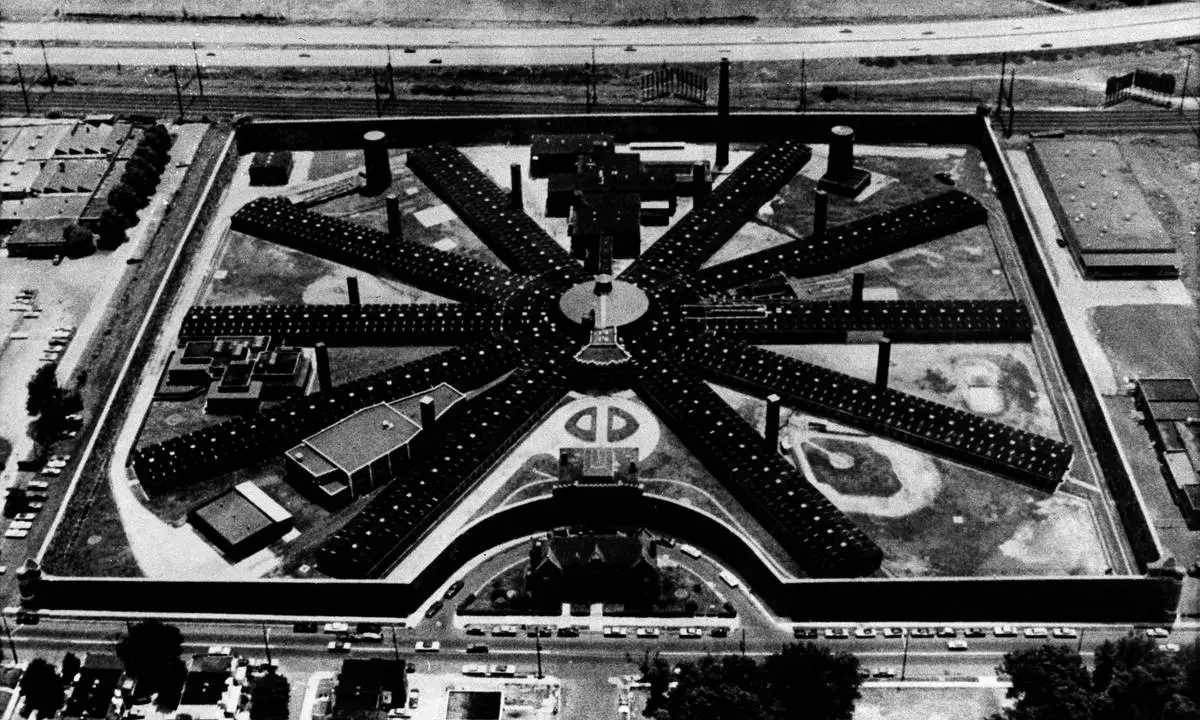

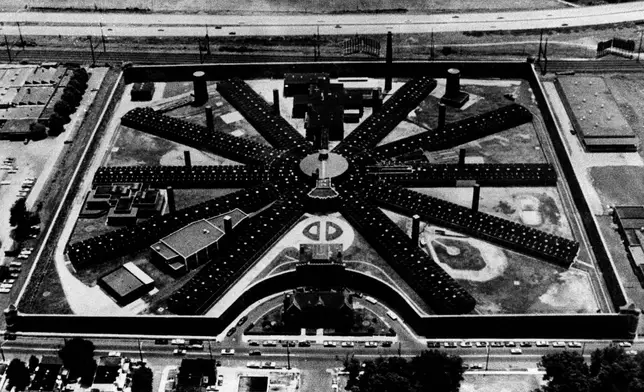

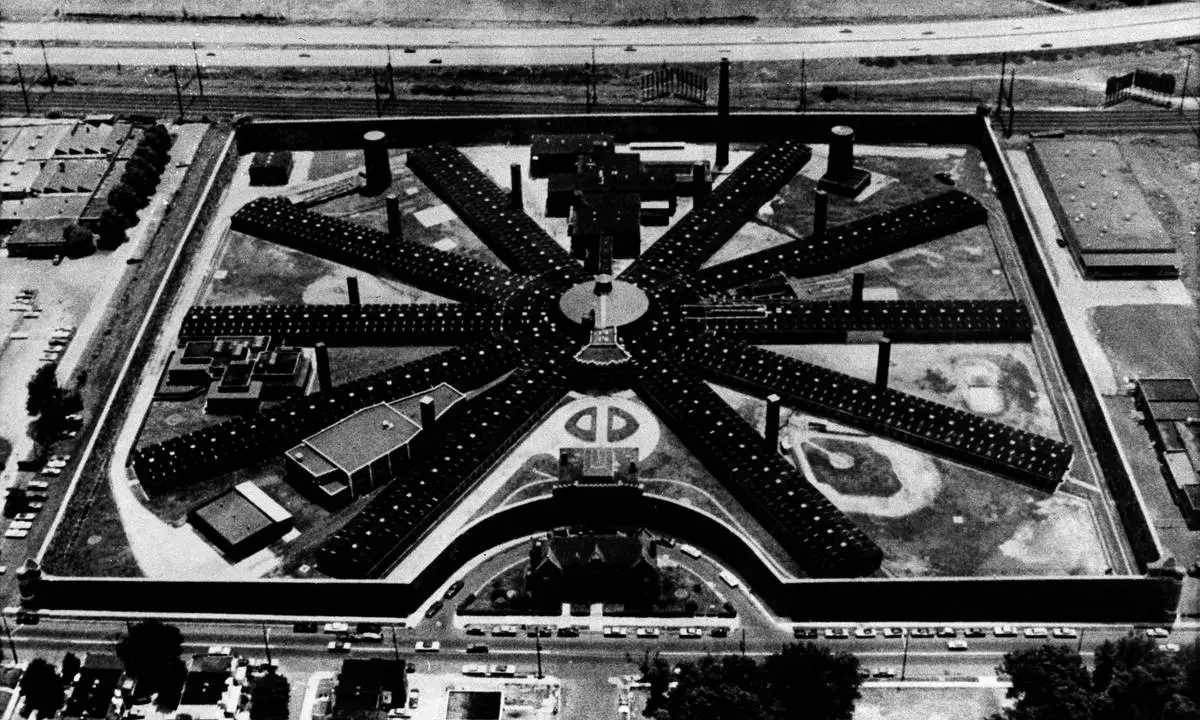

FILE - Holmesburg Prison, in the northeast section of Philadelphia, 1970. (AP Photo/Bill Achatz, File)

FILE - Edward Anthony speaks of his time at Holmesburg Prison in Philadelphia and the tests in which he participated while incarcerated there, Oct. 24, 2007. (Michael Bryant/The Philadelphia Inquirer via AP, File)

Herbert Rice, 79, poses for a photo at the University of Pennsylvania, on Wednesday, Oct. 23, 2024, in Philadelphia. Rice is one of many Black men who took part in prison medical testing from 1951 to 1974 at Philadelphia city prisons. (AP Photo/Laurence Kesterson)

Herbert Rice, 79, poses for a photo on Wednesday, Oct. 23, 2024, in Philadelphia. Rice is one of many Black men who took part in prison medical testing from 1951 to 1974 at Philadelphia city prisons. (AP Photo/Laurence Kesterson)

Herbert Rice, 79, speaks to other former inmates on Wednesday, Oct. 23, 2024, at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. (AP Photo/Laurence Kesterson)

Herbert Rice, 79, speaks to media at the University of Pennsylvania, on Wednesday, Oct. 23, 2024, in Philadelphia. (AP Photo/Laurence Kesterson)

Herbert Rice, 79, right, is embraced by Adrianne Jones-Alston, on Wednesday, Oct. 23, 2024, in Philadelphia. (AP Photo/Laurence Kesterson)

Herbert Rice, 79, poses for a photo at the University of Pennsylvania, on Wednesday, Oct. 23, 2024, in Philadelphia. Rice is one of many Black men who took part in prison medical testing from 1951 to 1974 at Philadelphia city prisons. (AP Photo/Laurence Kesterson)

“We were fertile ground for them people,” said Herbert Rice, a retired city worker from Philadelphia who said he has had lifelong psychiatric problems after taking an unknown drug at Holmesburg in the late 1960s that caused him to hallucinate. “It was just like dangling a carrot in front of a rabbit.”

The city and the University of Pennsylvania have issued formal apologies in recent years. Lawsuits have been mostly unsuccessful, except for a few small settlements. On Wednesday, families at a Penn law school event are set to seek reparations from the school and pharmaceutical companies that they say benefited from the Cold War-era research.

A University of Pennsylvania spokesperson said the school had no comment on the push for reparations.

The testing was led by Albert M. Kligman, a University of Pennsylvania dermatologist with research ties to the Army, the CIA and the pharmaceutical industry, according to author Allen Hornblum, who ran an adult literacy program at Holmesburg in the 1970s and saw the effects firsthand.

Medical testing in prisons was pervasive in the 1960s, with radiation studies conducted on people incarcerated in Washington and Oregon, cancer studies in Ohio and flash burn studies in Virginia, Hornblum said.

Human testing was also conducted on children in institutions, hospital patients and other vulnerable populations in much of the 20th century. The tide turned in the early 1970s, when outrage over the Tuskegee Syphilis Study — in which the U.S. government let Black men go untreated for syphilis to study the disease's impact — sparked an evolution in medical ethics, Hornblum said. Kligman defended his work until his death in 2010.

He is credited with being the first dermatologist to show a link between sun exposure and wrinkles. He patented Retin-A, a vitamin A derivative known generically as tretinoin, as an acne treatment in 1967 and received a new patent in 1986 after discovering the drug’s wrinkle-fighting ability.

“Retin-A was discovered and made at Holmesburg Prison,” Rice said. “They made millions and millions of dollars off the skin on our backs.”

In a 1966 interview with The Philadelphia Inquirer, Kligman described his first visit to Holmesburg with excitement, saying, “All I saw before me were acres of skin.”

Hornblum said there may be some parallels in the case of Henrietta Lacks, a Black woman whose descendants settled a lawsuit last year against a biomedical company that reproduced her cervical cells in 1951 without her permission. The resulting HeLa cells have gone on to become a cornerstone of modern medicine.

Rice, after serving about three years for burglary, later got his GED and built a 30-year career with the city recreation department, rising to a supervisory position. But he also did three stints in psychiatric hospitals, watched his marriage disintegrate and lost touch with his children for a time. As he nears his 80th birthday, he still takes lithium and can’t sleep without medication.

He said he would accept reparations but that they wouldn't change much for him.

"No amount of money can replace what was done to me, what was done to my children and wife. This thing was generational,” Rice said, later adding, “There’s nothing that can be done to make it right. I’m going to be like this the rest of my life.”

FILE - People incarcerated at the maximum security Holmesburg Prison in Philadelphia, turn out bullets for police revolvers, April 16, 1957. (AP Photo/Bill Ingraham, File)

FILE - Holmesburg Prison, in the northeast section of Philadelphia, 1970. (AP Photo/Bill Achatz, File)

FILE - Edward Anthony speaks of his time at Holmesburg Prison in Philadelphia and the tests in which he participated while incarcerated there, Oct. 24, 2007. (Michael Bryant/The Philadelphia Inquirer via AP, File)

Herbert Rice, 79, poses for a photo at the University of Pennsylvania, on Wednesday, Oct. 23, 2024, in Philadelphia. Rice is one of many Black men who took part in prison medical testing from 1951 to 1974 at Philadelphia city prisons. (AP Photo/Laurence Kesterson)

Herbert Rice, 79, poses for a photo on Wednesday, Oct. 23, 2024, in Philadelphia. Rice is one of many Black men who took part in prison medical testing from 1951 to 1974 at Philadelphia city prisons. (AP Photo/Laurence Kesterson)

Herbert Rice, 79, speaks to other former inmates on Wednesday, Oct. 23, 2024, at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. (AP Photo/Laurence Kesterson)

Herbert Rice, 79, speaks to media at the University of Pennsylvania, on Wednesday, Oct. 23, 2024, in Philadelphia. (AP Photo/Laurence Kesterson)

Herbert Rice, 79, right, is embraced by Adrianne Jones-Alston, on Wednesday, Oct. 23, 2024, in Philadelphia. (AP Photo/Laurence Kesterson)

Herbert Rice, 79, poses for a photo at the University of Pennsylvania, on Wednesday, Oct. 23, 2024, in Philadelphia. Rice is one of many Black men who took part in prison medical testing from 1951 to 1974 at Philadelphia city prisons. (AP Photo/Laurence Kesterson)

KAMPALA, Uganda (AP) — Uganda’s presidential election was plagued by widespread delays Thursday in addition to a days-long internet shutdown that has been criticized as an anti-democratic tactic in a country where the president has held office since 1986.

Some polling stations remained closed for up to four hours after the scheduled 7 a.m. start time due to “technical challenges," according to the nation's electoral commission, which asked polling officers to use paper registration records to ensure the difficulties did not “disenfranchise any voter.”

President Yoweri Museveni, 81, faces seven other candidates, including Robert Kyagulanyi, a musician-turned-politician best known as Bobi Wine, who is calling for political change.

The East African country of roughly 45 million people has 21.6 million registered voters. Polls were expected to close at 4 p.m., but voting was extended one hour until 5 p.m. local time. Results are constitutionally required to be announced in 48 hours.

In the morning, impatient crowds gathered outside polling stations expressing concerns over the delays. Umaru Mutyaba, a polling agent for a parliamentary candidate, said it was “frustrating” to be waiting outside a station in the capital Kampala.

“We can’t be standing here waiting to vote as if we have nothing else to do," he said.

Wine, the candidate, alleged electoral fraud, noting that biometric voter identification machines were not working at polling places and claiming that there was “ballot stuffing.”

Wine wrote in a post on X that his party's leaders had been arrested. “Many of our polling agents and supervisors abducted, and others chased off polling stations,” the post said.

Museveni told journalists he was notified that biometric machines weren't working at some stations and that he supported the electoral body's decision to revert to paper registration records. He did not comment on allegations of fraud.

Ssemujju Nganda, a prominent opposition figure and lawmaker seeking reelection in Kira municipality, told The Associated Press he had been waiting in line to vote for three hours.

Nganda said the delays likely would lead to apathy and low turnout in urban areas where the opposition has substantial support. "It’s going to be chaos,” he said.

Nicholas Sengoba, an independent analyst and newspaper columnist, said delays to the start of voting in urban, opposition areas favored the ruling party.

Emmanuel Tusiime, a young man who was among dozens prevented from entering a polling station in Kampala past closing time said the officials had prevented him from participating.

“My vote has not been counted, and, as you can see, I am not alone," he said he was left feeling “very disappointed.”

Uganda has not witnessed a peaceful transfer of presidential power since independence from British colonial rule six decades ago.

Museveni has served the third-longest term of any African leader and is seeking to extend his rule into a fifth decade. The aging president’s authority has become increasingly dependent on the military led by his son, Muhoozi Kainerugaba.

Museveni and Wine are reprising their rivalry from the previous election in 2021, when Wine appealed to mostly young people in urban areas. With voter turnout of 59%, Wine secured 35% of the ballots against Museveni’s 58%, the president’s smallest vote share since his first electoral campaign three decades ago.

The lead-up to Thursday's election produced concerns about transparency, the possibility of hereditary rule, military interference and possible vote tampering.

Uganda's internet was shut down Tuesday by the government communications agency, which cited misinformation, electoral fraud and incitement of violence. The shutdown has affected the public and disrupted critical sectors such as banking.

There has been heavy security leading up to voting, including military units deployed on the streets this week.

Amnesty International said security forces are engaging in a “brutal campaign of repression,” citing a Nov. 28 opposition rally in eastern Uganda where the military blocked exits and opened fire on supporters, killing one person.

Museveni urged voters to come out in large numbers during his final rally Tuesday.

“You go and vote, anybody who tries to interfere with your freedom will be crushed. I am telling you this. We are ready to put an end to this indiscipline,” he said.

The national electoral commission chairperson, Simon Byabakama, urged tolerance among Ugandans as they vote.

“Let us keep the peace that we have,” Byabakama said late Wednesday. “Let us be civil. Let us be courteous. Let’s be tolerant. Even if you know that this person does not support (your) candidate, please give him or her room or opportunity to go and exercise his or her constitutional right."

Authorities also suspended the activities of several civic groups during the campaign season. That Group, a prominent media watchdog, closed its office Wednesday after the interior ministry alleged in a letter that the group was involved in activities “prejudicial to the security and laws of Uganda.”

Veteran opposition figure Kizza Besigye, a four-time presidential candidate, remains in prison after he was charged with treason in February 2025.

Uganda opposition presidential candidate Robert Kyagulanyi Ssentamu, known as Bobi Wine, right, greets election observers, including former Nigerian President Goodluck Jonathan, at his home in Magere village on the outskirts of Kampala, Uganda, Wednesday, Jan. 14, 2026. (AP Photo/Hajarah Nalwadda)

Billboards of Uganda President and National Resistance Movement (NRM) presidential candidate Yoweri Museveni are seen in Kampala, Uganda, Tuesday, Jan. 13, 2026. (AP Photo/Samson Otieno)

Electoral workers deliver ballot boxes to a polling station during presidential election in Kampala, Uganda, Thursday, Jan. 15, 2026. (AP Photo/Brian Inganga)

Voters are reflected in a police officer's sunglasses as they wait in line after voting failed to start on time due to system failures during presidential election in Kampala, Uganda, Thursday, Jan. 15, 2026. (AP Photo/Brian Inganga)

Voters wait to cast their ballots during the presidential election in Kampala, Uganda, Thursday, Jan. 15, 2026. (AP Photo/Brian Inganga)