SAO PAULO (AP) — Sloths weren’t always slow-moving, furry tree-dwellers. Their prehistoric ancestors were huge — up to 4 tons (3.6 metric tons) — and when startled, they brandished immense claws.

For a long time, scientists believed the first humans to arrive in the Americas soon killed off these giant ground sloths through hunting, along with many other massive animals like mastodons, saber-toothed cats and dire wolves that once roamed North and South America.

Click to Gallery

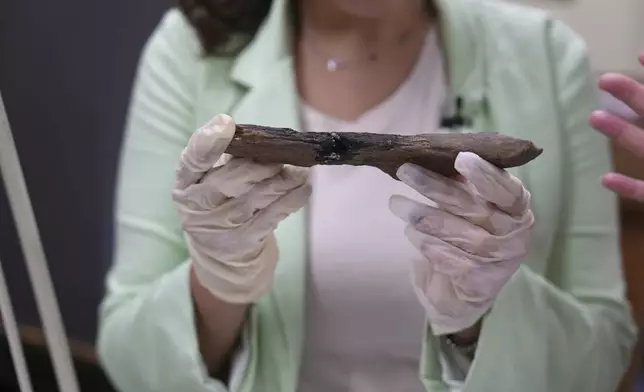

Researcher Mírian Pacheco holds a round, penny-sized sloth fossil dated to around 27,000 years ago, at the University of São Paulo, Brazil, on Sept 2, 2024, saying that unlike most other specimens, its surface is surprisingly smooth, the edges appear to have been deliberately polished, and there’s a tiny hole near one edge. (AP Photo/Christina Larson)

This illustration depicts giant sloths, humans and mastodons living alongside one another in central Brazil 27,000 years ago, during the Pleistocene period. (AP/Peter Hamlin)

Researcher Mírian Pacheco holds a round, penny-sized sloth fossil dated to around 27,000 years ago, at the University of São Paulo, Brazil, on Sept 2, 2024, saying that unlike most other specimens, its surface is surprisingly smooth, the edges appear to have been deliberately polished, and there’s a tiny hole near one edge. (AP Photo/Christina Larson)

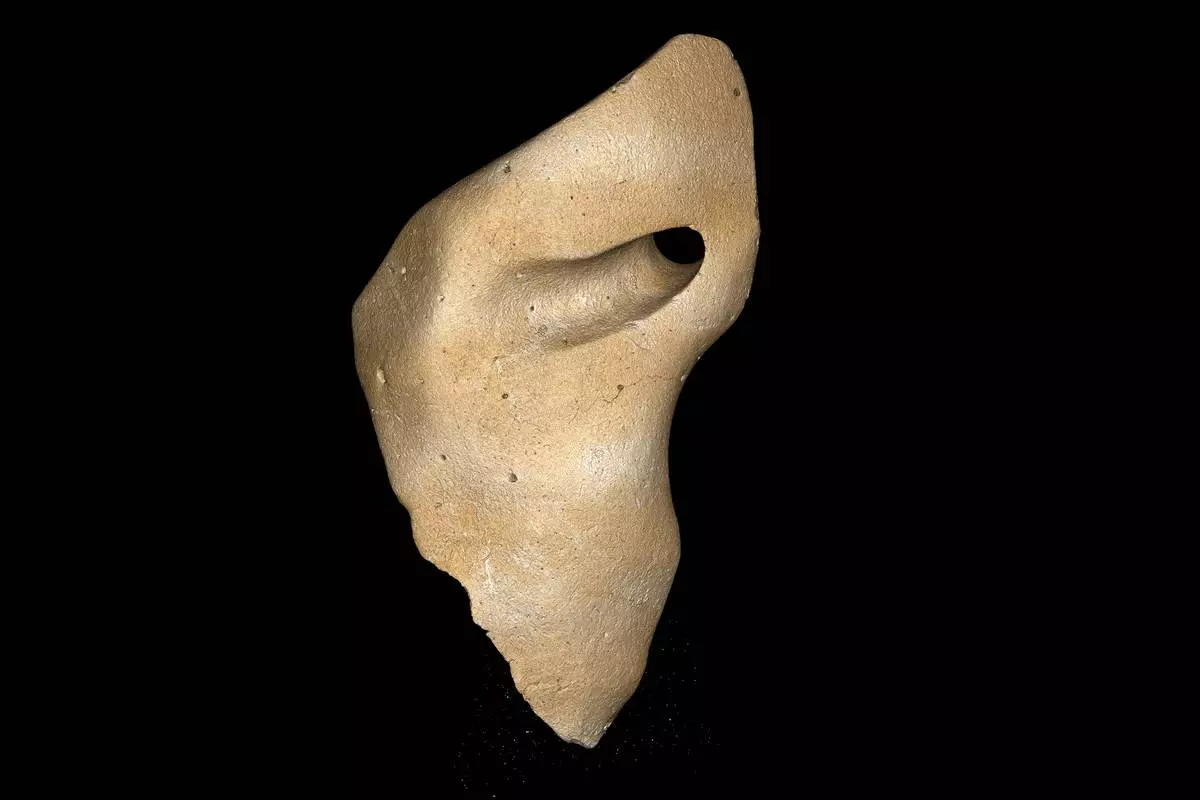

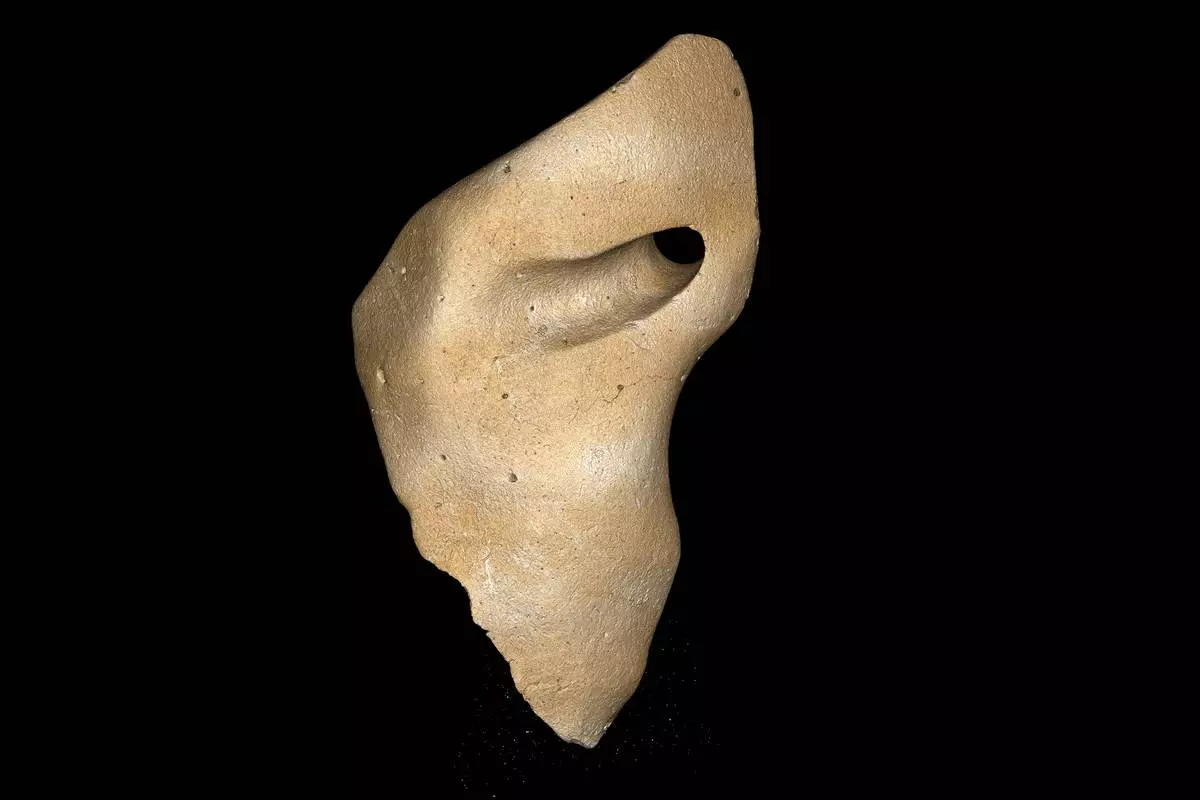

This image provided by researchers shows an artifact made of bony material from a giant sloth discovered at a rock shelter in Brazil, recovered from archaeological layers dated to 25,000 to 27,000 years ago. (Thaís Pansani, Pierre Gueriau via AP)

Thaís Pansani holds a giant sloth rib bone from central Brazil dated to about 13,000 to 15,000 years ago, which is thought to be burned by human-made fire, in the Smithsonian's National Taphonomy Reference Collection in Washington, on July 11, 2024. (AP Photo/Mary Conlon)

Thaís Pansani examines giant sloth bones dated to about 25,000 to 27,000 years ago from central Brazil, some of which appear to be burned by human-made fire, at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, on July 11, 2024. (AP Photo/Mary Conlon)

Thaís Pansani and Kay Behrensmeyer analyze a giant sloth rib bone from central Brazil, in the Smithsonian's National Taphonomy Reference Collection in Washington, D.C. on July 11, 2024. (AP Photo/Mary Conlon)

This photo provided by researchers shows the Santa Elina excavation site in the Mato Grosso state of Brazil. (Águeda Vilhena Vialou, Denis Vialou via AP)

This photo provided by researchers shows prehistoric drawings at the Santa Elina excavation site in the Mato Grosso state of Brazil. (Águeda Vilhena Vialou, Denis Vialou via AP)

This combination of illustrations provided by researchers in 2024 shows large animals which once roamed prehistoric North and South America. Top row from left, a glyptodon, a lestodon, and a horse. Bottom row from left, a mastodon, a saber-toothed cat and a toxodon. (Mauro Muyano via AP)

Paleontologist Thaís Pansani stands in front the reconstructed skeleton of a giant ground sloth at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington, on July 11, 2024. (AP Photo/Mary Conlon)

This photo provided by researchers shows fossils at the excavation site of Arroyo del Vizcaíno in Uruguay, where researchers have found evidence suggesting human occupation 30,000 years ago. (Martín Batallés via AP)

This illustration provided by researchers depicts a person carving an osteoderm from a giant sloth in Brazil about 25,000 to 27,000 years ago. (Júlia d'Oliveira via AP)

But new research from several sites is starting to suggest that people came to the Americas earlier — perhaps far earlier — than once thought. These findings hint at a remarkably different life for these early Americans, one in which they may have spent millennia sharing prehistoric savannas and wetlands with enormous beasts.

“There was this idea that humans arrived and killed everything off very quickly — what’s called ‘Pleistocene overkill,’” said Daniel Odess, an archaeologist at White Sands National Park in New Mexico. But new discoveries suggest that “humans were existing alongside these animals for at least 10,000 years, without making them go extinct."

Some of the most tantalizing clues come from an archaeological site in central Brazil, called Santa Elina, where bones of giant ground sloths show signs of being manipulated by humans. Sloths like these once lived from Alaska to Argentina, and some species had bony structures on their backs, called osteoderms — a bit like the plates of modern armadillos — that may have been used to make decorations.

In a lab at the University of Sao Paulo, researcher Mírian Pacheco holds in her palm a round, penny-sized sloth fossil. She notes that its surface is surprisingly smooth, the edges appear to have been deliberately polished, and there’s a tiny hole near one edge.

“We believe it was intentionally altered and used by ancient people as jewelry or adornment,” she said. Three similar “pendant” fossils are visibly different from unworked osteoderms on a table — those are rough-surfaced and without any holes.

These artifacts from Santa Elina are roughly 27,000 years old — more than 10,000 years before scientists once thought that humans arrived in the Americas.

Originally researchers wondered if the craftsmen were working on already old fossils. But Pacheco’s research strongly suggests that ancient people were carving “fresh bones” shortly after the animals died.

Her findings, together with other recent discoveries, could help rewrite the tale of when humans first arrived in the Americas — and the effect they had on the environment they found.

“There’s still a big debate,” Pacheco said.

Scientists know that the first humans emerged in Africa, then moved into Europe and Asia-Pacific, before finally making their way to the last continental frontier, the Americas. But questions remain about the final chapter of the human origins story.

Pacheco was taught in high school the theory that most archaeologists held throughout the 20th century. “What I learned in school was that Clovis was first,” she said.

Clovis is a site in New Mexico, where archaeologists in the 1920s and 1930s found distinctive projectile points and other artifacts dated to between 11,000 and 13,000 years ago.

This date happens to coincide with the end of the last Ice Age, a time when an ice-free corridor likely emerged in North America — giving rise to an idea about how early humans moved into the continent after crossing the Bering land bridge from Asia.

And because the fossil record shows the widespread decline of American megafauna starting around the same time — with North America losing 70% of its large mammals, and South America losing more than 80% — many researchers surmised that humans’ arrival led to mass extinctions.

“It was a nice story for a while, when all the timing lined up,” said paleoanthropologist Briana Pobiner at the Smithsonian Institution’s Human Origins Program. “But it doesn’t really work so well anymore.”

In the past 30 years, new research methods — including ancient DNA analysis and new laboratory techniques — coupled with the examination of additional archaeological sites and inclusion of more diverse scholars across the Americas, have upended the old narrative and raised new questions, especially about timing.

“Anything older than about 15,000 years still draws intense scrutiny,” said Richard Fariña, a paleontologist at the University of the Republic in Montevideo, Uruguay. “But really compelling evidence from more and more older sites keeps coming to light.”

In Sao Paulo and at the Federal University of Sao Carlos, Pacheco studies the chemical changes that occur when a bone becomes a fossil. This allows her team to analyze when the sloth osteoderms were likely modified.

“We found that the osteoderms were carved before the fossilization process” in “fresh bones” — meaning anywhere from a few days to a few years after the sloths died, but not thousands of years later.

Her team also tested and ruled out several natural processes, like erosion and animal gnawing. The research was published last year in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

One of her collaborators, paleontologist Thaís Pansani, recently based at the Smithsonian Institution, is analyzing whether similar-aged sloth bones found at Santa Elina were charred by human-made fires, which burn at different temperatures than natural wildfires.

Her preliminary results suggest that the fresh sloth bones were present at human campsites — whether burned deliberately in cooking, or simply nearby, isn’t clear. She is also testing and ruling out other possible causes for the black markings, such as natural chemical discoloration.

The first site widely accepted as older than Clovis was in Monte Verde, Chile.

Buried beneath a peat bog, researchers discovered 14,500-year-old stone tools, pieces of preserved animal hides, and various edible and medicinal plants.

“Monte Verde was a shock. You’re here at the end of the world, with all this organic stuff preserved," said Vanderbilt University archaeologist Tom Dillehay, a longtime researcher at Monte Verde.

Other archaeological sites suggest even earlier dates for human presence in the Americas.

Among the oldest sites is Arroyo del Vizcaíno in Uruguay, where researchers are studying apparent human-made “cut marks” on animal bones dated to around 30,000 years ago.

At New Mexico's White Sands, researchers have uncovered human footprints dated to between 21,000 and 23,000 years ago, as well as similar-aged tracks of giant mammals. But some archaeologists say it’s hard to imagine that humans would repeatedly traverse a site and leave no stone tools.

“They’ve made a strong case, but there are still some things about that site that puzzle me,” said David Meltzer, an archaeologist at Southern Methodist University. “Why would people leave footprints over a long period of time, but never any artifacts?"

Odess at White Sands said that he expects and welcomes such challenges. “We didn’t set out to find the oldest anything — we’ve really just followed the evidence where it leads,” he said.

While the exact timing of humans’ arrival in the Americas remains contested — and may never be known — it seems clear that if the first people arrived earlier than once thought, they didn’t immediately decimate the giant beasts they encountered.

And the White Sands footprints preserve a few moments of their early interactions.

As Odess interprets them, one set of tracks shows “a giant ground sloth going along on four feet” when it encounters the footprints of a small human who’s recently dashed by. The huge animal “stops and rears up on hind legs, shuffles around, then heads off in a different direction."

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Science and Educational Media Group. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

This illustration depicts giant sloths, humans and mastodons living alongside one another in central Brazil 27,000 years ago, during the Pleistocene period. (AP/Peter Hamlin)

Researcher Mírian Pacheco holds a round, penny-sized sloth fossil dated to around 27,000 years ago, at the University of São Paulo, Brazil, on Sept 2, 2024, saying that unlike most other specimens, its surface is surprisingly smooth, the edges appear to have been deliberately polished, and there’s a tiny hole near one edge. (AP Photo/Christina Larson)

This image provided by researchers shows an artifact made of bony material from a giant sloth discovered at a rock shelter in Brazil, recovered from archaeological layers dated to 25,000 to 27,000 years ago. (Thaís Pansani, Pierre Gueriau via AP)

Thaís Pansani holds a giant sloth rib bone from central Brazil dated to about 13,000 to 15,000 years ago, which is thought to be burned by human-made fire, in the Smithsonian's National Taphonomy Reference Collection in Washington, on July 11, 2024. (AP Photo/Mary Conlon)

Thaís Pansani examines giant sloth bones dated to about 25,000 to 27,000 years ago from central Brazil, some of which appear to be burned by human-made fire, at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, on July 11, 2024. (AP Photo/Mary Conlon)

Thaís Pansani and Kay Behrensmeyer analyze a giant sloth rib bone from central Brazil, in the Smithsonian's National Taphonomy Reference Collection in Washington, D.C. on July 11, 2024. (AP Photo/Mary Conlon)

This photo provided by researchers shows the Santa Elina excavation site in the Mato Grosso state of Brazil. (Águeda Vilhena Vialou, Denis Vialou via AP)

This photo provided by researchers shows prehistoric drawings at the Santa Elina excavation site in the Mato Grosso state of Brazil. (Águeda Vilhena Vialou, Denis Vialou via AP)

This combination of illustrations provided by researchers in 2024 shows large animals which once roamed prehistoric North and South America. Top row from left, a glyptodon, a lestodon, and a horse. Bottom row from left, a mastodon, a saber-toothed cat and a toxodon. (Mauro Muyano via AP)

Paleontologist Thaís Pansani stands in front the reconstructed skeleton of a giant ground sloth at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington, on July 11, 2024. (AP Photo/Mary Conlon)

This photo provided by researchers shows fossils at the excavation site of Arroyo del Vizcaíno in Uruguay, where researchers have found evidence suggesting human occupation 30,000 years ago. (Martín Batallés via AP)

This illustration provided by researchers depicts a person carving an osteoderm from a giant sloth in Brazil about 25,000 to 27,000 years ago. (Júlia d'Oliveira via AP)

COLORADO SPRINGS, Colo. (AP) — Derrick Johnson buried his mother’s ashes beneath a golden dewdrop tree with purple blossoms at his home on Maui’s Haleakalā Volcano, fulfilling her wish of a final resting place looking over her grandchildren.

Then the FBI called.

It was Feb. 4, 2024, and Johnson was teaching an eighth grade gym class.

“'Are you the son of Ellen Lopes?'” a woman asked, Johnson recalled in an interview with The Associated Press.

There had been an incident, and an FBI agent would fly out to explain, the caller said. Then she asked: “'Did you use Return to Nature for a funeral home?'”

“'You should probably google them,'” she added.

In the clatter of the weight room, Johnson typed “Return to Nature” into his cellphone. Dozens of news reports appeared, details popping out in a blur.

Hundreds of bodies stacked on top of each other. Inches of body decomposition fluid. Swarms of bugs. Investigators traumatized. Governor declares state of emergency.

Johnson felt nauseated and his chest constricted, forcing the breath from his lungs. He pushed himself out of the building as another teacher heard his cries and came running.

Two FBI agents visited Johnson the following week, confirming his mother's body was among 189 that Return to Nature's owners, Jon and Carie Hallford, had stashed in a Colorado building between 2019 and Oct. 4, 2023, when the bodies were found.

It was one of the largest discoveries of decaying bodies at a funeral home in the U.S. Lawmakers overhauled the state's lax funeral home regulations. And besides handing over fake ashes to grieving families, the Hallfords also admitted to defrauding the federal government out of nearly $900,000 in pandemic-era aid for small businesses.

Even as the Hallfords’ bills went unpaid, authorities said they spent lavishly on Tiffany jewelry, luxury cars and laser-body sculpting, pocketing about $130,000 clients paid for cremations.

They were arrested in Oklahoma in November 2023 and charged with abusing nearly 200 corpses.

Hundreds of families learned from officials that the ashes they ceremonially spread or kept close weren’t actually their loved ones’ remains. The bodies of their mothers, fathers, grandparents, children and babies had moldered in a room-temperature building in Colorado.

Jon Hallford will be sentenced Friday, facing between 30 to 50 years in prison, and Carie Hallford in April after a judge accepted their plea agreements in December. Attorneys for Jon and Carie Hallford did not respond to an AP request for comment.

Johnson, 45, who's suffered panic attacks since the FBI called, promised himself that he would speak at Hallford's sentencing and ask for the maximum penalty.

“When the judge passes out how long you’re going to jail, and you walk away in cuffs,” he said, “you’re gonna hear me.”

Jon and Carie Hallford were a husband-and-wife team who advertised “green burials" without embalming as well as cremation at their Return to Nature funeral home in Colorado Springs.

She would greet grieving families, guiding them through their loved ones' final journey. He was less seen.

Johnson called the funeral home in early February 2023, the week his mother died. Carie Hallford assured him she would take good care of his mother, Johnson said.

Days later, she handed Johnson a blue box containing a zip-tied plastic bag with gray powder, saying those were his mother's ashes.

"She lied to me over the phone. She lied to me through email. She lied to me in person,” Johnson told the AP.

The following day, the box lay surrounded by flowers and photos of Ellen Marie Shriver-Lopes at a memorial service at a Holiday Inn in Colorado Springs.

Johnson sprinkled rose petals over it as a preacher said: “Ashes to ashes, dust to dust."

On Sept. 9, 2023, surveillance footage showed a man appearing to be Jon Hallford walk inside a building owned by Return to Nature in the town of Penrose, outside Colorado Springs, according to an arrest affidavit.

Camera footage inside showed a body lying on a gurney wearing a diaper and hospital socks. The man flipped it onto the floor.

Then he “appeared to wipe the remaining decomposition from the gurney onto other bodies in the room,” before wheeling what appeared to be two more bodies into the building, the affidavit said.

In a text to his wife, Hallford said, “while I was making the transfer, I got people juice on me,” according to court testimony.

Johnson grew up with his mother in an affordable-housing complex in Colorado Springs, where she knew everyone.

Johnson's father wasn't around much; at 5 years old, Johnson remembers seeing him punch his mom, sending her careening into a table, then onto a guitar, breaking it.

It was Lopes who taught Johnson to shave and hollered from the bleachers at his football games.

Neighborhood kids called her “mom,” some sleeping on the couch when they needed a place to stay and a warm meal. She would chat with Jehovah’s Witnesses because she didn’t want to be rude. With a life spent in social work, Lopes would say: “If you have the ability and you have the voice to help: Help.”

Johnson spoke with his mother nearly everyday. After diabetes left her blind and bedridden at age 65, she'd ask Johnson to describe what her grandchildren looked like over the phone.

It was Super Bowl Sunday in 2023 when her heart stopped.

Johnson, who had flown in from Hawaii to be at her bedside, clutched her warm hand and held it until it was cold.

Detective Sgt. Michael Jolliffe and Laura Allen, the county’s deputy coroner, stood outside the Penrose building on Oct. 3, 2023, according to the 50-page arrest affidavit.

A sign on the door read “Return to Nature Funeral Home” and listed a phone number. When Jolliffe called it, it was disconnected. Cracked concrete and yellow stalks of grass encircled the building. At back was a shabby hearse with expired registration. A window air conditioner hummed.

Someone had told Jolliffe of a rank smell coming from the building the day before, the affidavit said.

One neighbor told an AP reporter they thought it came from a septic tank; another said her daughter's dog always headed to the building whenever it got off-leash.

It was reminiscent of rancid manure or rotting fish, and struck anyone downwind of the building.

Jolliffe and Allen spotted a dark stain under the door and on the building’s stucco exterior. They thought it looked like fluids they had seen during investigations with decaying bodies, the affidavit said.

But the building’s windows were covered and they couldn’t see inside.

Allen contacted the Colorado Department of Regulatory Agencies, which oversees funeral homes, which got in touch with Jon Hallford. Hallford agreed to show an inspector inside the next afternoon.

Inspector Joseph Berry arrived, but Hallford didn’t show.

Berry found a small opening in one of the window coverings, the affidavit said. Peering through, he saw white plastic bags that looked like body bags on the floor.

A judge issued a search warrant that week.

Donning protective suits, gloves, boots and respirators, investigators entered the 2,500-square-foot (232-square-meter) building on Oct. 5, 2023, according to the affidavit.

Inside, they found a large bone grinder and next to it a bag of Quikrete that investigators suspected was used to mimic ashes. Bodies were stacked in nearly a dozen rooms, including the bathroom, sometimes so high they blocked doorways, the affidavit said.

There were 189.

Some had decayed for years, others several months, according to the affidavit. Many were in body bags, some wrapped in sheets and duct tape. Others were half-exposed, on gurneys or in plastic totes, or lay with no covering, it said.

Investigators believed the Hallfords were experimenting with water cremation, which can dissolve a body in several hours, the document said. There were swarms of bugs and maggots.

Body bags were filled with fluid, according to the affidavit. Some had ripped. Five-gallon buckets had been placed to catch the leaks. Removal teams “trudged through layers of human decomposition on the floor,” it said.

Investigators identified bodies using fingerprints, hospital bracelets and medical implants, the affidavit said. It said one body was supposed to be buried in Pikes Peak National Cemetery.

Investigators exhumed the wooden casket at the burial site of the U.S. Army veteran, who served in Vietnam and the Persian Gulf. Inside was a woman’s deteriorated body, wrapped in duct tape and plastic sheets.

The veteran's body was discovered in the Penrose building, covered in maggots.

Following the call from the FBI, Johnson promised himself he would speak at the Hallfords' sentencing. But he struggled to talk about what had happened even with close friends, let alone in front of a judge and the Hallfords.

For months, Johnson obsessed over the case, reading dozens of news reports, often glued to his phone until one of his children would interrupt him to play.

When he shut his eyes, he said he imagined trudging through the building with “maggots, flies, centipedes. There’s rats, they’re feasting.” He asked a preacher if his mother’s soul had been trapped there. She reassured him it hadn’t. When an episode of the zombie show “The Walking Dead” came on, he broke down.

Johnson started seeing a therapist and was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder. He joined Zoom meetings with other victims' relatives as the number grew from dozens to hundreds.

After Lopes’ body was identified, Johnson flew in March 2024 to Colorado, where his mother's remains lay in a brown box in a crematorium.

“I don’t think you blame me, but I still want to tell you I’m sorry,” he recalled saying, placing his hand on the box.

Then Lopes’ body was loaded into the cremator and Johnson pushed the button.

Johnson has slowly improved with therapy, engaging more with his students and children. He practiced speaking at the Hallfords' sentencings while in therapy. Closing his eyes, he envisioned standing in front of the judge — and the Hallfords.

“Justice is, it’s the part that is missing from this whole equation,” he said. “Maybe somehow this justice frees me.”

“And then there’s part of me that’s scared it won’t, because it probably won’t.”

Derrick Johnson, whose mother's body was one of 189 left to decay in the Return to Nature Funeral Home in Penrose, Colo., holds family photos in his aunt's home in Colorado Springs, Colo., on Thursday, Feb. 5, 2026. (AP Photo/Thomas Peipert)

Photographs of Ellen Marie Shriver-Lopes, whose body was one of 189 left to decay in the Return to Nature Funeral Home in Penrose, Colo., are stacked in her sister's home in Colorado Springs, Colo., on Thursday, Feb. 5, 2026. (AP Photo/Thomas Peipert)

FILE - A hearse and van sit outside the Return to Nature Funeral Home, in Penrose, Colo., Oct. 6, 2023. (AP Photo/David Zalubowski, File)

Derrick Johnson, whose mother's body was one of 189 left to decay in the Return to Nature Funeral Home in Penrose, Colo., poses for a portrait in Colorado Springs, Colo., on Thursday, Feb. 5, 2026. (AP Photo/Thomas Peipert)

Derrick Johnson, whose mother's body was one of 189 left to decay in the Return to Nature Funeral Home in Penrose, Colo., holds photos of her in Colorado Springs, Colo., on Thursday, Feb. 5, 2026. (AP Photo/Thomas Peipert)