BUDAPEST, Hungary (AP) — A senior Hungarian government official close to Prime Minister Viktor Orbán was hit Tuesday with U.S. sanctions for his alleged involvement in corruption in Hungary, a rare step against a sitting official in an allied country.

The Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control sanctioned Antal Rogán for corruption while in office. A key figure in Orbán’s government, Rogán is accused of using his position to broker favorable business deals with government-aligned businesspeople, a key part of European Union penalties against Hungary that have withheld billions in funding over official corruption concerns.

Speaking at a news conference in Budapest on Tuesday, U.S. Ambassador to Hungary David Pressman said Rogán was “a primary architect, implementer and beneficiary” of systemic corruption in Hungary which he described as a “kleptocratic ecosystem.”

“For too long, senior government officials in Hungary have used positions of power to enrich themselves and their families, moving significant funds from the public purse into private pockets,” Pressman said, adding that there were “many others involved” in such corruption within Hungary's government.

The head of Orbán's cabinet office, Rogán oversees the engineering of wide-reaching government communication campaigns that are credited with being instrumental in maintaining Orbán’s power since 2010. Known among critics in Hungary as the “propaganda minister,” Rogán rarely appears in public or gives interviews, but is a veteran advisor to Orbán and also oversees Hungary’s secret services.

State Department spokesperson Matthew Miller said in a statement Tuesday that Rogan’s activity “is emblematic of the broader climate of impunity in Hungary where key elements of the state have been captured by oligarchs and undemocratic actors.”

The authority used to designate Rogán is a Trump-era executive order that implements the Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act, which targets human rights abusers and corruption around the world.

The sanctions brought by the outgoing Biden administration reflect U.S. efforts in the last four years to address concerns in Washington that Orbán has led Hungary, a member of the EU and a NATO member, to abandon democratic principles while pursuing closer ties with Russia and China.

Orbán, who backs Donald Trump, has expressed certainty that U.S.-Hungarian relations would improve once the president-elect takes office. Orbán made three visits to Trump’s Mar-a-Lago residence in 2024, while Trump has spoken positively about him.

Ambassador Pressman, whose tenure in Hungary will end this month, has been the subject of intense criticism by Orbán’s government, which accuses him of attempting to interfere in Hungary’s internal affairs.

Responding to the sanctions, Hungary's foreign minister, Péter Szijjártó, wrote on social media: “This is personal revenge against Antal Rogán by the ambassador sent by the failed U.S. administration to Hungary, but who is now leaving ingloriously and without success."

"How nice that in a few days’ time the United States will be led by people who see our country as a friend and not an enemy,” Szijjártó wrote.

The Treasury Department in 2023 placed sanctions on the International Investment Bank, which relocated its headquarters to Hungary’s capital from Moscow in 2019, arguing it served as a conduit for Russian espionage within the EU and NATO.

Hungary soon after withdrew its stakes in the bank.

Hussein reported from Washington. Associated Press writer Matthew Lee in Washington contributed reporting.

FILE - Hungary's Prime Minister Viktor Orban addresses a media conference at the end of an EU summit in Brussels, Dec. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Omar Havana)

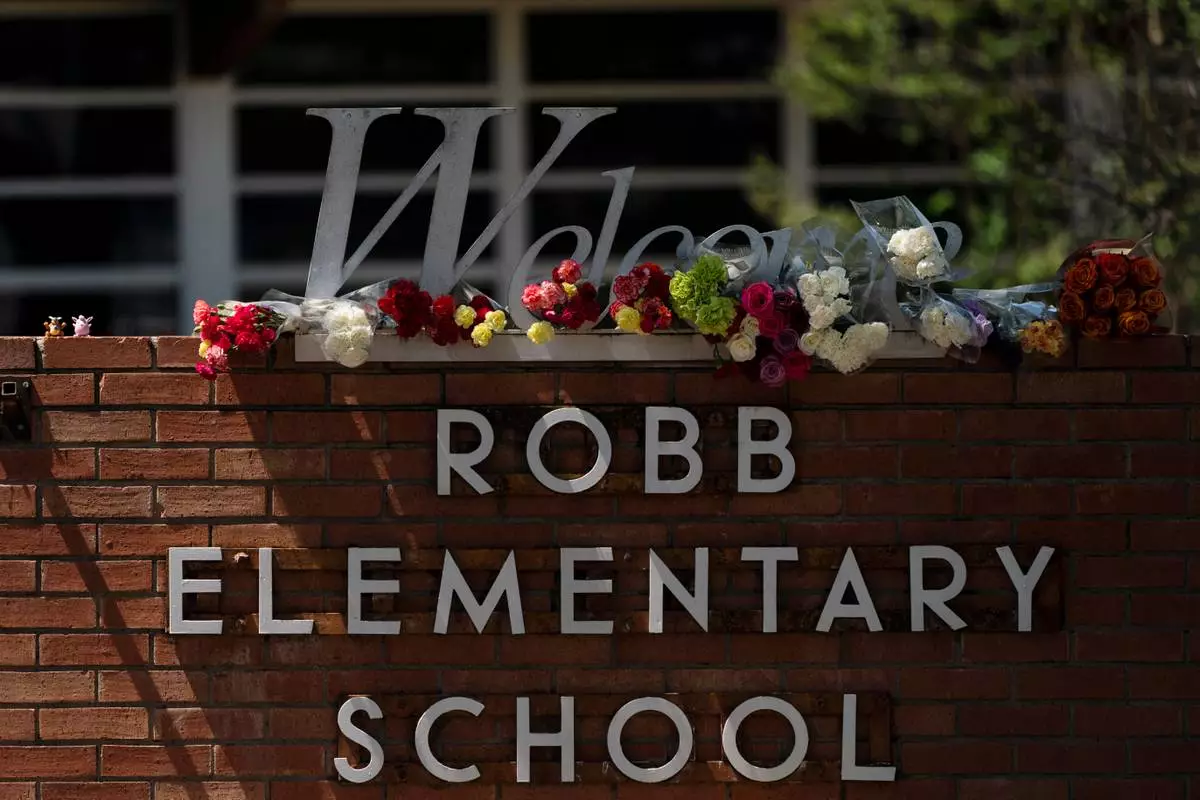

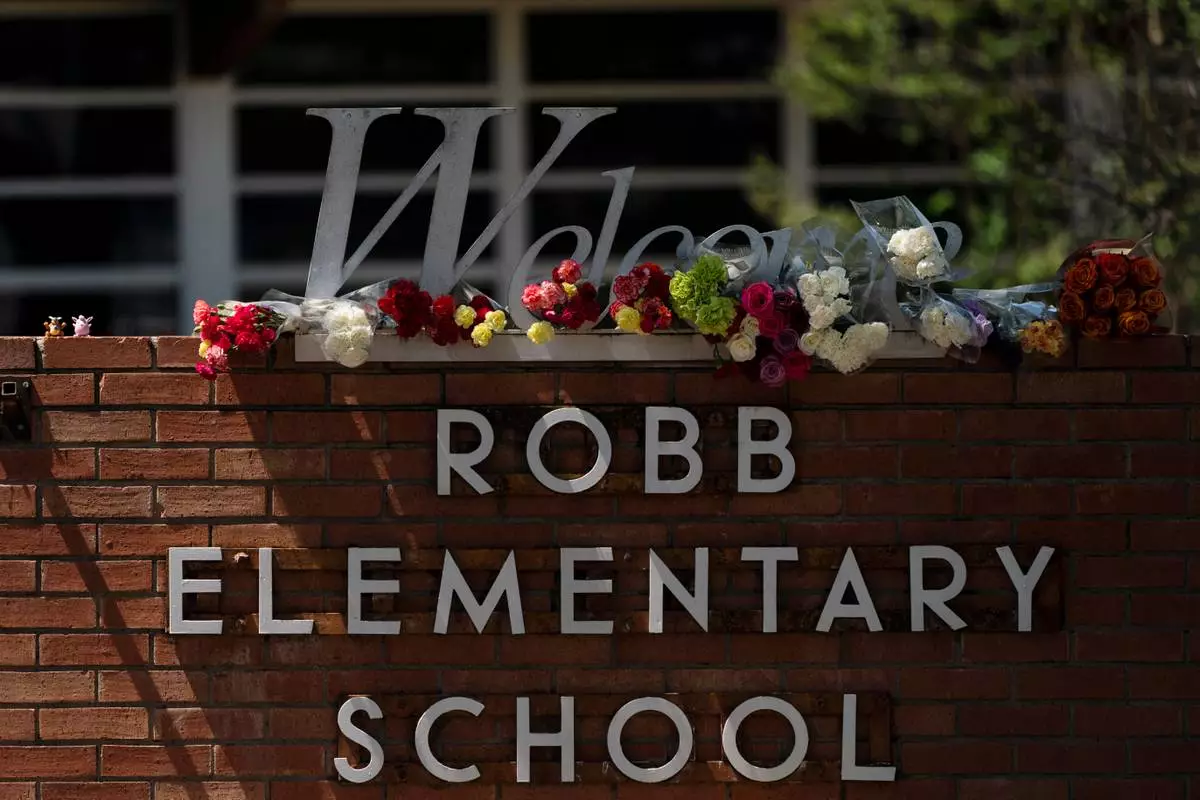

HOUSTON (AP) — Former Uvalde, Texas, schools police Officer Adrian Gonzales was among the first officers to arrive at Robb Elementary after a gunman opened fire on students and teachers.

Prosecutors allege that instead of rushing in to confront the shooter, Gonzales failed to take action to protect students. Many families of the 19 fourth-grade students and two teachers who were killed believe that if Gonzales and the nearly 400 officers who responded had confronted the gunman sooner instead of waiting more than an hour, lives might have been saved.

More than 3½ years since the killings, the first criminal trial over the delayed law enforcement response to one of the deadliest school shootings in U.S. history is set to begin.

It’s a rare case in which a police officer could be convicted for allegedly failing to act to stop a crime and protect lives.

Here’s a look at the charges and the legal issues surrounding the trial.

Gonzales was charged with 29 counts of child endangerment for those killed and injured in the May 2022 shooting. The indictment alleges he placed children in “imminent danger” of injury or death by failing to engage, distract or delay the shooter and by not following his active shooter training. The indictment says he did not advance toward the gunfire despite hearing shots and being told where the shooter was located.

Each child endangerment count carries a potential sentence of up to two years in prison.

State and federal reviews of the shooting cited cascading problems in law enforcement training, communication, leadership and technology and questioned why officers from multiple agencies waited so long before confronting and killing the gunman, Salvador Ramos.

Gonzales’ attorney, Nico LaHood, said his client is innocent and public anger over the shooting is being misdirected.

“He was focused on getting children out of that building,” LaHood, said. “He knows where his heart was and what he tried to do for those children.”

Jury selection in Gonzales’ trial is scheduled to begin Jan. 5 in Corpus Christi, about 200 miles (320 kilometers) southeast of Uvalde. The trial was moved after defense attorneys argued Gonzales could not receive a fair trial in Uvalde.

Gonzales, 52, and former Uvalde schools police chief Pete Arredondo are the only officers charged. Arredondo was charged with multiple counts of child endangerment and abandonment. His trial has not been scheduled, and he is also seeking a change of venue.

Prosecutors have not explained why only Gonzales and Arredondo were charged. Uvalde County District Attorney Christina Mitchell did not respond to a request for comment.

It’s “extremely unusual” for an officer to stand trial for not taking an action, said Sandra Guerra Thompson, a University of Houston Law Center professor.

“At the end of the day, you’re talking about convicting someone for failing to act and that’s always a challenge,” Thompson said, “because you have to show that they failed to take reasonable steps.”

Phil Stinson, a criminal justice professor at Bowling Green State University who maintains a nationwide database of roughly 25,000 cases of police officers arrested since 2005, said a preliminary search found only two similar prosecutions.

One involved a Florida sheriff’s deputy, Scot Peterson, who was charged after the 2018 Parkland school massacre for allegedly failing to confront the shooter — the first such prosecution in the U.S. for an on-campus shooting. He was acquitted by a jury in 2023.

The other was the 2022 conviction of former Baltimore police officer Christopher Nguyen for failing to protect an assault victim. The Maryland Supreme Court overturned that conviction in July, ruling prosecutors had not shown Nguyen had a legal duty to protect the victim.

The justices in Maryland cited a prior U.S. Supreme Court decision on the public duty doctrine, which holds that government officials like police generally owe a duty to the public at large rather than to specific individuals unless a special relationship exists.

Michael Wynne, a Houston criminal defense attorney and former prosecutor not involved in the case, said securing a conviction will be difficult.

“This is clearly gross negligence. I think it’s going to be difficult to prove some type of criminal malintent,” Wynne said.

But Thompson, the law professor, said prosecutors may nonetheless be well positioned.

“You’re talking about little children who are being slaughtered and a very long delay by a lot of officers,” she said. “I just feel like this is a different situation because of the tremendous harm that was done to so many children.”

Associated Press writer Jim Vertuno in Austin, Texas, contributed.

Follow Juan A. Lozano: https://x.com/juanlozano70

FILE - Flowers are placed around a welcome sign outside Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, May 25, 2022, to honor the victims killed in a shooting at the school. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong, File)

Velma Lisa Duran, sister of Robb Elementary teacher Irma Garcia, cries as she reflects on the 2022 Uvalde, Texas, school shooting during an interview on Dec. 19, 2025, in San Antonio. (AP Photo/Kin Man Hui)

Velma Lisa Duran, sister of Robb Elementary teacher Irma Garcia, poses with photos of her sister and brother-in-law, Joe Garcia, as she reflects on the 2022 Uvalde, Texas, school shooting on Dec. 19, 2025, in San Antonio. (AP Photo/Kin Man Hui)

FILE - This booking image provided by the Uvalde County, Texas, Sheriff's Office shows Adrian Gonzales, a former police officer for schools in Uvalde, Texas. (Uvalde County Sheriff's Office via AP, File)

FILE - Crosses with the names of shooting victims are placed outside Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, May 26, 2022. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong, File)