FORT LAUDERDALE, Fla. (AP) — Brad Marchand is many things. Sarcastic, most definitely. A pest on the ice, absolutely. Someone who doesn't mind a little bonus physicality, goes without saying. His “little ball of hate” nickname even got repeated once by President Barack Obama.

The Florida Panthers knew all of this when they acquired him.

And then they learned something else. Marchand is ... likeable?

“Good person and fun to be around,” Panthers defenseman Aaron Ekblad said. “Great poker player as well.”

The Toronto Maple Leafs probably believe that. To use the poker term, they've been all-in against Marchand a few times at playoff time and always lost.

One of hockey's best rivalries — Toronto fans vs. Marchand — resumes Monday night, when the Maple Leafs host the Panthers in Game 1 of an Eastern Conference second-round series. He tends to be booed whenever he touches the puck in Toronto, the fans there remembering how their team went up against Marchand and the Boston Bruins four previous times, all those series going to Game 7, all of them going Boston's way.

The fans don't like him. Marchand doesn't mind. There are bigger priorities. There's a Cup to chase.

“To be honest, I never really cared,” Marchand said. "Fans get a very small insight of who we are as people. They watch the games and they build opinions on players off who they are on the ice. Fans that I meet and interact with, I think they have a different perception.”

Make no mistake, there seems to be a perception about the Panthers. Florida forward Matthew Tkachuk isn't exactly adored in other buildings around the NHL. Same goes for another Florida forward, Sam Bennett. Like Marchand, they're tough, rugged, unafraid of contact. It would probably shock fans in other markets to learn that Tkachuk — like the rest of his family — support a slew of causes quietly without seeking attention for doing so. And Bennett's passion is finding sheltered animals forever homes; with every goal he scores, he pays the adoption fee to have another dog or cat join a new family.

On-ice perception is one thing, Panthers coach Paul Maurice said. Actual reality is another.

“Those three men are wonderful to the support staff, trainers, coaches, everybody, flight attendants, all the people who help move our team and don't get on camera,” Maurice said. “They're just fantastic to watch. They make you a better person just watching them.”

Marchand might talk a lot on the ice — chirping is one of his favorite hobbies — but he's been downright gentlemanly since joining the Panthers. He's played in 15 games since the trade; he's taken only four minor penalties in that span. He's settled in on Florida's third line, been a key part of the penalty-kill, perfectly content to do his job.

The idea of someone who was the Bruins' captain joining Florida — a playoff rival — might have seemed unlikely at best a few months ago. But someone who turns 37 on May 11 knows that there might not be too many more chances to win another Stanley Cup, so he embraced the move to Florida.

“Everyone’s path is different," Marchand said. “Mine usually was built off of emotion and it was very intense and very competitive and sometimes when you do that you cross the line and have to play a certain way that gets me engaged all the time. Sometimes it rubs people the wrong way and it comes off in a way people don’t like. But I don’t play the game for anybody outside of myself and my team.”

It was not the easiest of transitions for Marchand — who had spent his entire NHL career in Boston — after the trade. That's not because of personality or past playoff battles; it's because he was injured and recovering. His rehab work was done on a different schedule than basically the rest of the team, even keeping him from traveling with the club in the early going. It delayed his full acclimation.

Once he could play again, things fell into place with the Panthers quickly.

“I’ve seen a lot of guys kind of come in to the teams I was on in the past. And there’s some guys that came in the wrong way and guys came in right way," Marchand said. "I tried to learn from that and just kind of come in the right way and not step on toes and kind of watch and learn how things are done.”

Panthers fans throw toy plastic rats onto the ice after wins, a nod back to the team's 1995-96 season. As the story goes, Florida’s Scott Mellanby killed a rat in the locker room with his stick before opening night that season and then scored two goals in that game. “Rat trick” was the phrase that was born from that, and the rats have been part of Florida lore ever since.

These days, when the rats rain down, Panthers teammates fire them at Marchand's legs before he can leave the ice. It's a badge of honor. Panthers fans — who were never exactly thrilled by seeing him before the trade, of course — used to throw them at Marchand. They throw them for him now.

“It means we won,” Marchand said. “That's a good thing.”

AP NHL playoffs: https://apnews.com/hub/stanley-cup and https://apnews.com/hub/nhl

Linesman Devin Berg (87) separates Tampa Bay Lightning right wing Nikita Kucherov (86) and Florida Panthers center Brad Marchand (63) during the second period in Game 2 of an NHL hockey Stanley Cup first-round playoff series, Thursday, April 24, 2025, in Tampa, Fla. (AP Photo/Chris O'Meara)

Florida Panthers center Brad Marchand (63) is taken down by Tampa Bay Lightning defenseman Ryan McDonagh (27) and center Conor Geekie (14) during the third period in Game 2 of an NHL hockey Stanley Cup first-round playoff series, Thursday, April 24, 2025, in Tampa, Fla. (AP Photo/Chris O'Meara)

Florida Panthers center Brad Marchand (63) works against Tampa Bay Lightning defenseman J.J. Moser (90) during the third period in Game 5 of an NHL hockey Stanley Cup first-round playoff series, Wednesday, April 30, 2025, in Tampa, Fla. (AP Photo/Chris O'Meara)

CARACAS, Venezuela (AP) — U.S. President Donald Trump's threat to cut off Venezuelan oil sales could devastate a country already wrangling with years of spiraling crises.

The prospect added to Venezuelans' collective anxiety over their country's future on Wednesday. But after years of political, social and economic challenges, Venezuelans also treated the threat like another inconvenience — even when it could bring back the shortages of food, gasoline and other goods that defined the country over the last decade.

“Well, we’ve already had so many crises, shortages of so many things — food, gasoline — that one more ... well, one doesn’t worry anymore,” Milagro Viana said while waiting to catch a bus in Caracas, the country's capital.

Trump on Tuesday announced he was ordering a blockade of all “sanctioned oil tankers” into Venezuela, ramping up pressure on Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro, who has been charged with narcoterrorism in the United States.

Trump’s escalation came after U.S. forces last week seized an oil tanker off Venezuela’s coast after a buildup of military forces in the region.

Venezuela has the world’s largest proven oil reserves and produces about 1 million barrels a day. The country's economy depends on the industry, with more than 80% of output exported.

Maduro’s government has relied on a shadowy fleet of unflagged tankers to smuggle crude into global supply chains since 2017, when the first Trump administration began imposing sanctions on Venezuela's oil industry.

In a post on social media announcing the blockade, Trump alleged that Venezuela was using oil to fund drug trafficking and other crimes. He vowed to continue the military buildup until Venezuela gives the U.S. oil, land and other assets.

On Wednesday, Trump demanded that Venezuela return assets it seized from U.S. oil companies years ago, justifying anew his announcement a day earlier of a “blockade” against tankers hauling crude to or from the South American country that face American sanctions.

David Smilde, a Tulane University professor who has studied Venezuela for more than three decades, said a full implementation of Trump’s threat will cause a huge economic contraction because oil represents 90% of the country’s exports.

“This is a country that traditionally imports a lot, not just finished goods, but most intermediate goods — everything from toilet paper to food containers,” Smilde said. “If you don’t have foreign currency coming up, that just brings the whole economy to a halt.”

That could lead to price increases as well as shortages of food and other basic goods. Fuel could also become scarce because some of the tankers ship Venezuela fluids that are used to produce gasoline for the local market.

“Things are going to get tough here,” Pedro Arangura said while waiting for a remittance store to open. “We have to put up with it. Nobody wants it, but it’s going to happen.”

Arangura said material difficulties could lead to Maduro’s ouster, echoing what Venezuela’s opposition has been telling supporters in recent months.

Nearby, Ismael Chirino, like Arangura, said he believes the population will “resist” whatever challenges result from Trump's latest move. But, Chirino said, people will do so to maintain Maduro in office.

“We held on. We didn’t have gas, we didn’t have gasoline, we didn’t have money, and yet, we withstood all of that,” Chirino said, referring to the second half of the 2010s, when the country's economy came undone and shortages were widespread. “I think they need to think very carefully if the U.S. wants to take over our wealth and all our territory."

The White House has said the military buildup, which began in the Caribbean and later expanded to the eastern Pacific Ocean, is meant to stop the flow of drugs into the U.S. The operation has killed at least 95 people, with Venezuelans among them.

Maduro has denied the drug accusations. He and his allies have repeatedly said that the operation’s true purpose is to force a government change in Venezuela. They have also claimed that the U.S. is after Venezuela's vast oil and mineral resources.

Smilde said Trump’s threat was a gift to Chavismo, the political movement that Maduro inherited from the late President Hugo Chávez, his predecessor and mentor. Chávez became president in 1999 with promises to uplift the poor and used an oil bonanza in the 2000s to push a self-described socialist agenda.

“There are few actions that any U.S. president has taken in the last 25 years that have better fit Chavismo’s line than Donald Trump’s tweet last night,” Smilde said. “They have been saying this from the beginning, ‘The U.S. wants our oil.’ So, finally, the discourse has the evidence.”

Follow AP’s coverage of Latin America and the Caribbean at https://apnews.com/hub/latin-america

People ride a boat along the coast in Macuto, Venezuela, Wednesday, Dec. 17, 2025. (AP Photo/Ariana Cubillos)

Residents and fisherman stand near Macuto beach in Venezuela, Wednesday, Dec. 17, 2025. (AP Photo/Ariana Cubillos)

Fresh tuna is for sale on Macuto beach in Venezuela, Wednesday, Dec. 17, 2025. (AP Photo/Ariana Cubillos)

A man looks out at the sea in the city of La Guaira, Venezuela, where the nation's flag flies, Wednesday, Dec. 17, 2025. (AP Photo/Ariana Cubillos)

A vendor sells inflatables on Macuto beach in Venezuela, Wednesday, Dec. 17, 2025. (AP Photo/Ariana Cubillos)

Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth arrives to brief members of Congress on military strikes near Venezuela, Tuesday, Dec. 16, 2025, at the Capitol in Washington. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth departs the Capitol after briefing members of Congress on military strikes near Venezuela, Tuesday, Dec. 16, 2025, in Washington. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

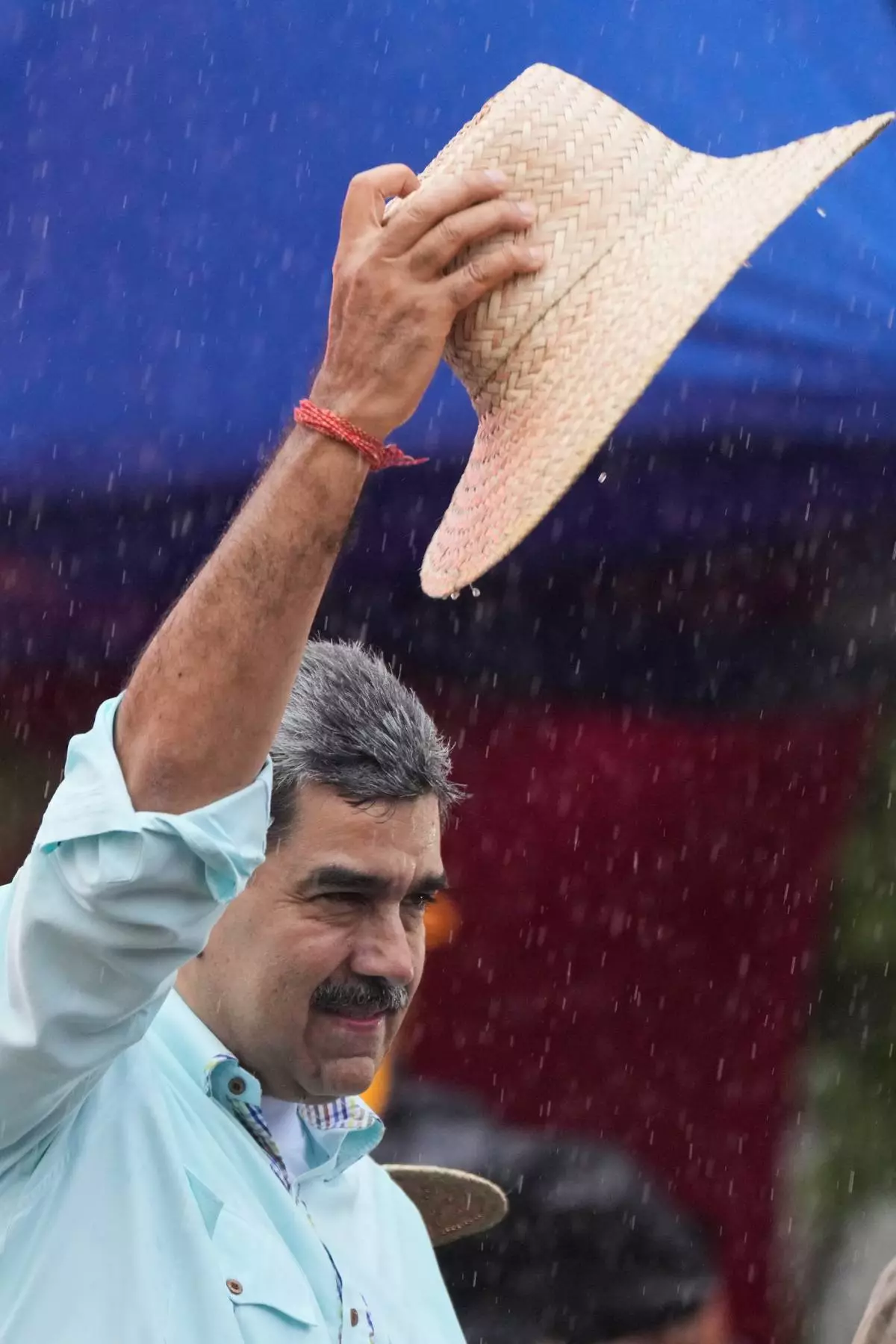

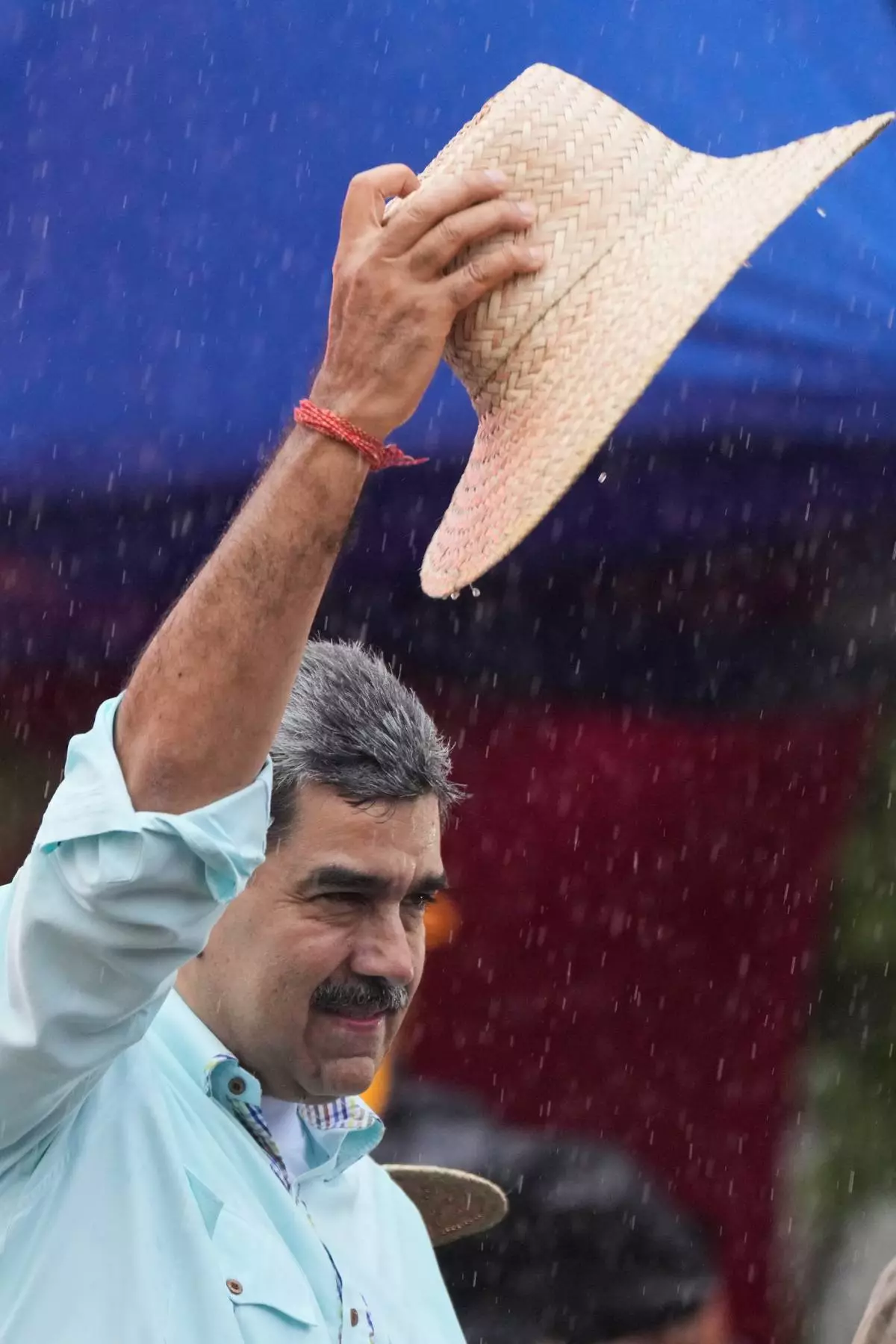

FILE - President Nicolas Maduro addresses supporters during a rally marking the anniversary of the Battle of Santa Ines, which took place during Venezuela's 19th-century Federal War, in Caracas, Venezuela, Wednesday, Dec. 10, 2025. (AP Photo/Ariana Cubillos, File)

A man looks out at the sea in the city of La Guaira, Venezuela, where the nation's flag flies, Wednesday, Dec. 17, 2025. (AP Photo/Ariana Cubillos)