RIO DE JANEIRO (AP) — If you have been to Rio de Janeiro’ beaches, this probably sounds familiar: samba music drifting from a nearby kiosk, caipirinha cocktails sold by hawkers, chairs sprawled across the sand.

Now that may become harder to find, unless the vendors have the right permits.

Click to Gallery

A vendor walks with his hats and beachwear along Ipanema Beach in Rio de Janeiro, Sunday, May 25, 2025. (AP Photo/Bruna Prado)

Beachgoers walk past a vendor's stand of beachwear on Ipanema Beach in Rio de Janeiro, Sunday, May 25, 2025. (AP Photo/Bruna Prado)

A beach kiosk sits on the Ipanema Beach boardwalk in Rio de Janeiro, Sunday, May 25, 2025. (AP Photo/Bruna Prado)

Vendor Leandro Azevedo carries a tray of fruit cocktail to customers on Ipanema Beach in Rio de Janeiro, Sunday, May 25, 2025. (AP Photo/Bruna Prado)

A vendor walks with his hats and beachwear along Ipanema Beach in Rio de Janeiro, Sunday, May 25, 2025. (AP Photo/Bruna Prado)

Beachgoers gather on the Ipanema Beach boardwalk in Rio de Janeiro, Sunday, May 25, 2025. (AP Photo/Bruna Prado)

Mayor Eduardo Paes issued a decree in mid-May establishing new rules for the city’s waterfront saying he wants to preserve urban order, public safety and the environment, as well as promote peaceful relations between tourists and residents.

The new measures are due to come into force on June 1, and they outlaw food and drink sales, chair rentals, loudspeakers and even live music in kiosks without official permits. Also, beach huts will only be allowed to have a number rather than the often-creative names many are currently known by.

Some have welcomed the move to tackle what they perceive as chaotic activity on the beach, but others say the decree threatens Rio’s dynamic beach culture and the livelihoods of many musicians and local vendors who may find it difficult or impossible to get permits.

The move to regulate music on Rio’s beachfronts has particularly struck a nerve.

“It’s difficult to imagine Rio de Janeiro without bossa nova, without samba on the beach,” said Julio Trindade, who works as a DJ in the kiosks. “While the world sings the Girl from Ipanema, we won’t be able to play it on the beach.”

The restrictions on music amounts to “silencing the soul of the waterfront. It compromises the spirit of a democratic, musical, vibrant, and authentic Rio,” Orla Rio, a concessionaire who manages more than 300 kiosks, said in a statement.

Some are seeking ways to stop the implementation of the decree or at least modify it to allow live music without a permit. But so far to little avail.

The nonprofit Brazilian Institute of Citizenship, which defends social and consumer rights, filed a lawsuit last week requesting the suspension of the articles restricting live music, claiming that the measure compromises the free exercise of economic activity. A judge ruled that the group is not a legitimate party to present a complaint, and the nonprofit is appealing the decision.

Also last week, Rio’s municipal assembly discussed a bill that aims to regulate the use of the coastline, including beaches and boardwalks. It backs some aspects of the decree such as restricting amplified music on the sand but not the requirement that kiosks have permits for live musicians. The proposal still needs to formally be voted on, and it's not clear if that will happen before June 1.

If approved, the bill will take precedence over the decree.

Economic activity on Rio’s beaches, excluding kiosks, bars and restaurants, generates an estimated 4 billion reais (around $710 million) annually, according to a 2022 report by Rio’s City Hall.

Millions of foreigners and locals hit Rio’s beaches every year and many indulge in sweet corn, grilled cheese or even a bikini or electronic devices sold by vendors on the sprawling sands.

Local councilwoman Dani Balbi lashed out against the bill on social media.

“What’s the point of holding big events with international artists and neglecting the people who create culture every day in the city?” she said last week on Instagram, in reference to the huge concerts by Lady Gaga earlier this month and Madonna last year.

“Forcing stallholders to remove the name of their businesses and replace it with numbers compromises the brand identity and the loyalty of customers, who use that location as a reference,” Balbi added.

News of the decree seeking to crack down on unregistered hawkers provoked ripples of anger and fear among peddlers.

“It’s tragic,” said Juan Marcos, a 24-year-old who sells prawns on sticks on Copacabana beach and lives in a nearby favela, or low-income urban community. “We rush around madly, all to bring a little income into the house. What are we going to do now?”

City Hall doesn’t give enough permits to hawkers on the beach, said Maria de Lourdes do Carmo, 50, who heads the United Street Vendors’ Movement — known by its acronym MUCA.

“We need authorizations, but they’re not given,” said Lourdes do Carmo, who is known as Maria of the Street Vendors. The city government did not respond to a request for the number of authorizations given last year.

Following the outcry, the city government emphasized that some rules were already in place in a May 21 statement. The town hall added that it is talking to all affected parties to understand their demands and is considering adjustments.

Maria Lucia Silva, a 65-year-old resident of Copacabana who was walking back from the seafront with a pink beach chair under her arm, said she had been expecting City Hall to act.

“Copacabana is a neighborhood for elderly people (… ). Nobody pays a very high property tax or absurd rents to have such a huge mess,” Silva said, slamming the noise and pollution on the beach.

For Rebecca Thompson, 53, who hails from Wales and was again visiting Rio after a five-week trip last year, the frenzy is part of the charm.

“There’s vibrancy, there’s energy. For me, there’s always been a strong sense of community and acceptance. I think it would be very sad if that were to go,” she said.

A vendor walks with his hats and beachwear along Ipanema Beach in Rio de Janeiro, Sunday, May 25, 2025. (AP Photo/Bruna Prado)

Beachgoers walk past a vendor's stand of beachwear on Ipanema Beach in Rio de Janeiro, Sunday, May 25, 2025. (AP Photo/Bruna Prado)

A beach kiosk sits on the Ipanema Beach boardwalk in Rio de Janeiro, Sunday, May 25, 2025. (AP Photo/Bruna Prado)

Vendor Leandro Azevedo carries a tray of fruit cocktail to customers on Ipanema Beach in Rio de Janeiro, Sunday, May 25, 2025. (AP Photo/Bruna Prado)

A vendor walks with his hats and beachwear along Ipanema Beach in Rio de Janeiro, Sunday, May 25, 2025. (AP Photo/Bruna Prado)

Beachgoers gather on the Ipanema Beach boardwalk in Rio de Janeiro, Sunday, May 25, 2025. (AP Photo/Bruna Prado)

HOUSTON (AP) — Former Uvalde, Texas, schools police Officer Adrian Gonzales was among the first officers to arrive at Robb Elementary after a gunman opened fire on students and teachers.

Prosecutors allege that instead of rushing in to confront the shooter, Gonzales failed to take action to protect students. Many families of the 19 fourth-grade students and two teachers who were killed believe that if Gonzales and the nearly 400 officers who responded had confronted the gunman sooner instead of waiting more than an hour, lives might have been saved.

More than 3½ years since the killings, the first criminal trial over the delayed law enforcement response to one of the deadliest school shootings in U.S. history is set to begin.

It’s a rare case in which a police officer could be convicted for allegedly failing to act to stop a crime and protect lives.

Here’s a look at the charges and the legal issues surrounding the trial.

Gonzales was charged with 29 counts of child endangerment for those killed and injured in the May 2022 shooting. The indictment alleges he placed children in “imminent danger” of injury or death by failing to engage, distract or delay the shooter and by not following his active shooter training. The indictment says he did not advance toward the gunfire despite hearing shots and being told where the shooter was located.

Each child endangerment count carries a potential sentence of up to two years in prison.

State and federal reviews of the shooting cited cascading problems in law enforcement training, communication, leadership and technology and questioned why officers from multiple agencies waited so long before confronting and killing the gunman, Salvador Ramos.

Gonzales’ attorney, Nico LaHood, said his client is innocent and public anger over the shooting is being misdirected.

“He was focused on getting children out of that building,” LaHood, said. “He knows where his heart was and what he tried to do for those children.”

Jury selection in Gonzales’ trial is scheduled to begin Jan. 5 in Corpus Christi, about 200 miles (320 kilometers) southeast of Uvalde. The trial was moved after defense attorneys argued Gonzales could not receive a fair trial in Uvalde.

Gonzales, 52, and former Uvalde schools police chief Pete Arredondo are the only officers charged. Arredondo was charged with multiple counts of child endangerment and abandonment. His trial has not been scheduled, and he is also seeking a change of venue.

Prosecutors have not explained why only Gonzales and Arredondo were charged. Uvalde County District Attorney Christina Mitchell did not respond to a request for comment.

It’s “extremely unusual” for an officer to stand trial for not taking an action, said Sandra Guerra Thompson, a University of Houston Law Center professor.

“At the end of the day, you’re talking about convicting someone for failing to act and that’s always a challenge,” Thompson said, “because you have to show that they failed to take reasonable steps.”

Phil Stinson, a criminal justice professor at Bowling Green State University who maintains a nationwide database of roughly 25,000 cases of police officers arrested since 2005, said a preliminary search found only two similar prosecutions.

One involved a Florida sheriff’s deputy, Scot Peterson, who was charged after the 2018 Parkland school massacre for allegedly failing to confront the shooter — the first such prosecution in the U.S. for an on-campus shooting. He was acquitted by a jury in 2023.

The other was the 2022 conviction of former Baltimore police officer Christopher Nguyen for failing to protect an assault victim. The Maryland Supreme Court overturned that conviction in July, ruling prosecutors had not shown Nguyen had a legal duty to protect the victim.

The justices in Maryland cited a prior U.S. Supreme Court decision on the public duty doctrine, which holds that government officials like police generally owe a duty to the public at large rather than to specific individuals unless a special relationship exists.

Michael Wynne, a Houston criminal defense attorney and former prosecutor not involved in the case, said securing a conviction will be difficult.

“This is clearly gross negligence. I think it’s going to be difficult to prove some type of criminal malintent,” Wynne said.

But Thompson, the law professor, said prosecutors may nonetheless be well positioned.

“You’re talking about little children who are being slaughtered and a very long delay by a lot of officers,” she said. “I just feel like this is a different situation because of the tremendous harm that was done to so many children.”

Associated Press writer Jim Vertuno in Austin, Texas, contributed.

Follow Juan A. Lozano: https://x.com/juanlozano70

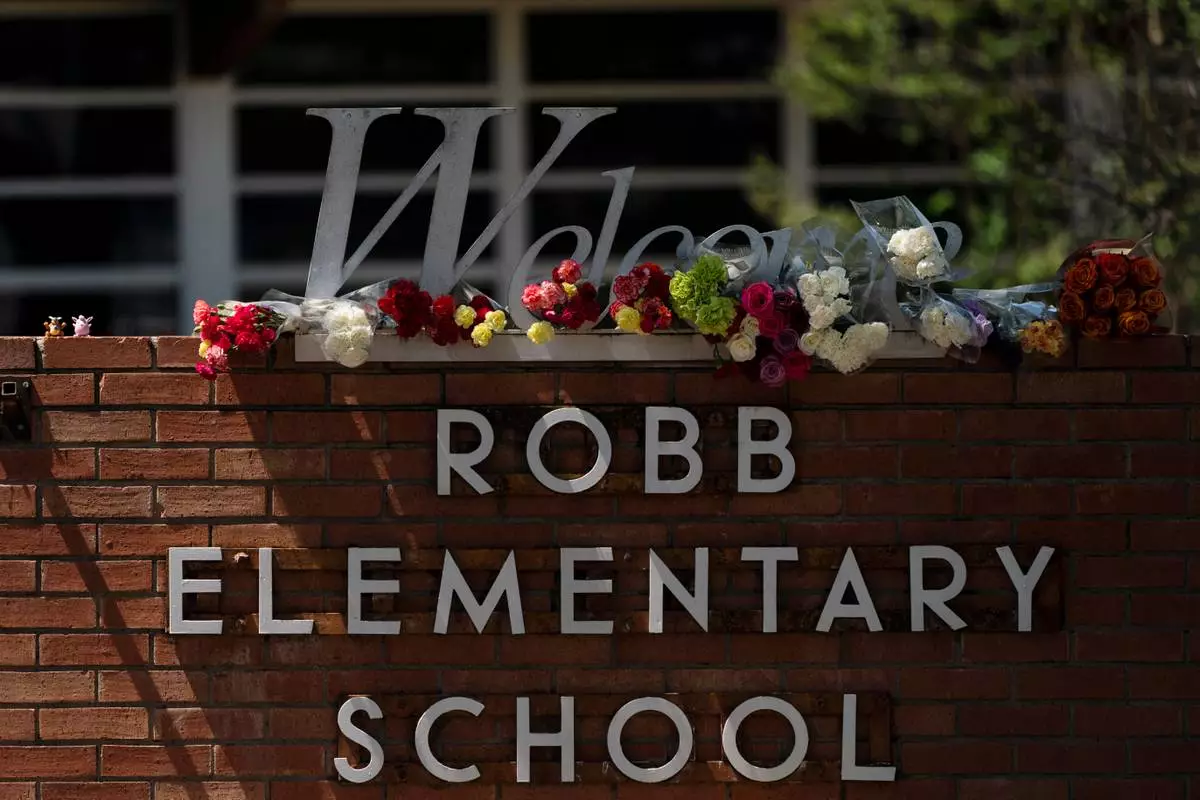

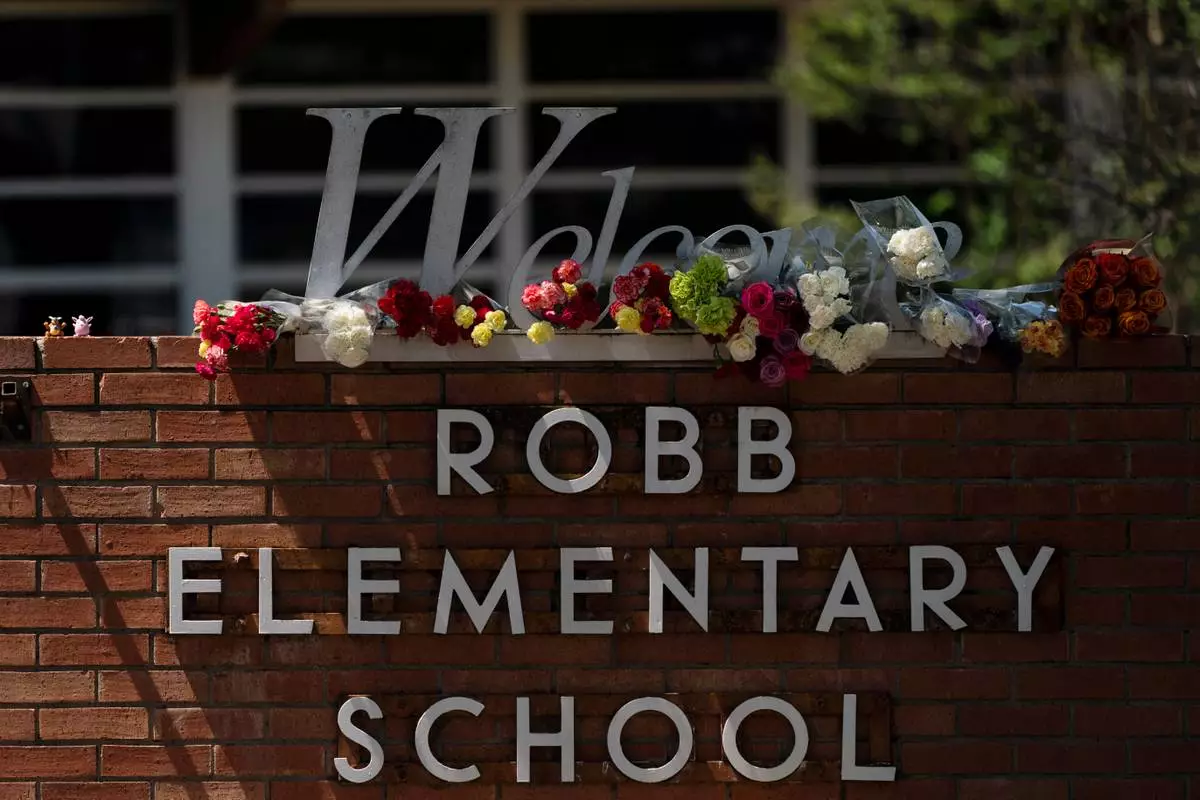

FILE - Flowers are placed around a welcome sign outside Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, May 25, 2022, to honor the victims killed in a shooting at the school. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong, File)

Velma Lisa Duran, sister of Robb Elementary teacher Irma Garcia, cries as she reflects on the 2022 Uvalde, Texas, school shooting during an interview on Dec. 19, 2025, in San Antonio. (AP Photo/Kin Man Hui)

Velma Lisa Duran, sister of Robb Elementary teacher Irma Garcia, poses with photos of her sister and brother-in-law, Joe Garcia, as she reflects on the 2022 Uvalde, Texas, school shooting on Dec. 19, 2025, in San Antonio. (AP Photo/Kin Man Hui)

FILE - This booking image provided by the Uvalde County, Texas, Sheriff's Office shows Adrian Gonzales, a former police officer for schools in Uvalde, Texas. (Uvalde County Sheriff's Office via AP, File)

FILE - Crosses with the names of shooting victims are placed outside Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, May 26, 2022. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong, File)