Last month, Scottie Scheffler made mention of a trend in golf design that rubs him wrong — removing trees from courses.

This week, the world's best player and favorite to win the U.S. Open will play a course that did just that, but didn't become one bit easier the way some layouts do when the trees go away. Under the dark of night three decades ago, the people in charge of Oakmont Country Club started cutting down trees. They didn’t stop until some 15,000 had been removed.

The project reimagined one of America’s foremost golf cathedrals and started a trend of tree cutting that continues to this day.

While playing a round on YouTube with influencer Grant Horvat, Scheffler argued that modern pro golf — at least at most stops on the PGA Tour — has devolved into a monotonous cycle of “bomb and gouge”: Hit drive as far as possible, then gouge the ball out of the rough from a shorter distance if the tee shot is off line.

“They take out all the trees and they make the greens bigger and they typically make the fairways a little bigger, as well,” Scheffler said. “And so, the only barrier to guys just trying to hit it as far as they want to or need to, it’s trees.”

Scheffler and the rest in the 156-man field that tees off Thursday should be so lucky.

While the latest Oakmont renovation, in 2023, did make greens bigger, fairways are never wide at the U.S. Open and they won’t be this week.

Tree-lined or not, Oakmont has a reputation as possibly the toughest of all the U.S. Open (or any American) courses, which helps explain why it is embarking on its record 10th time hosting it. In the two Opens held there since the tree-removal project was completed, the deep bunkers, serpentine drainage ditches and lightning-fast greens have produced winning scores of 5-over par (Angel Cabrera in 2007) and 4 under (Dustin Johnson in 2016).

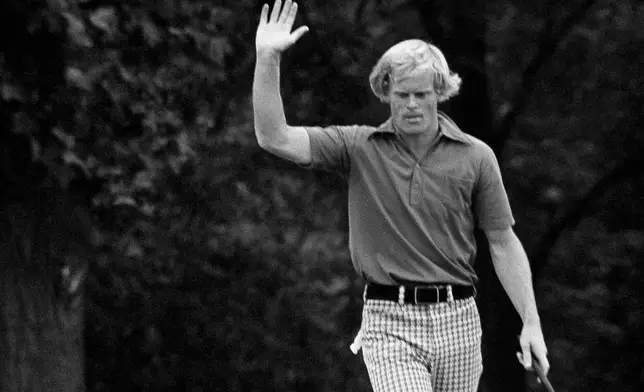

In an ironic twist that eventually led to where we (and Oakmont) are today, the layout was completely lined with trees in 1973 when Johnny Miller shot 63 on Sunday to win the U.S. Open. That record stood for 50 years, and the USGA followed up with a course setup so tough in 1974 that it became known as “The Massacre at Winged Foot” -- won by Hale Irwin with a score of 7-over par.

“Everybody was telling me it was my fault,” Miller said in a look back at the ’74 Open with Golf Digest. “It was like a backhanded compliment. The USGA denied it, but years later, it started leaking out that it was in response to what I did at Oakmont. Oakmont was supposed to be the hardest course in America.”

It might still be.

In a precursor to what could come this week, Rory McIlroy and Adam Scott played practice rounds last Monday in which McIlroy said he made a 7 on the par-4 second and Scott said he hit every fairway on the front nine and still shot 3 over.

While Oakmont leaned into tree removal, there are others who aren’t as enthused.

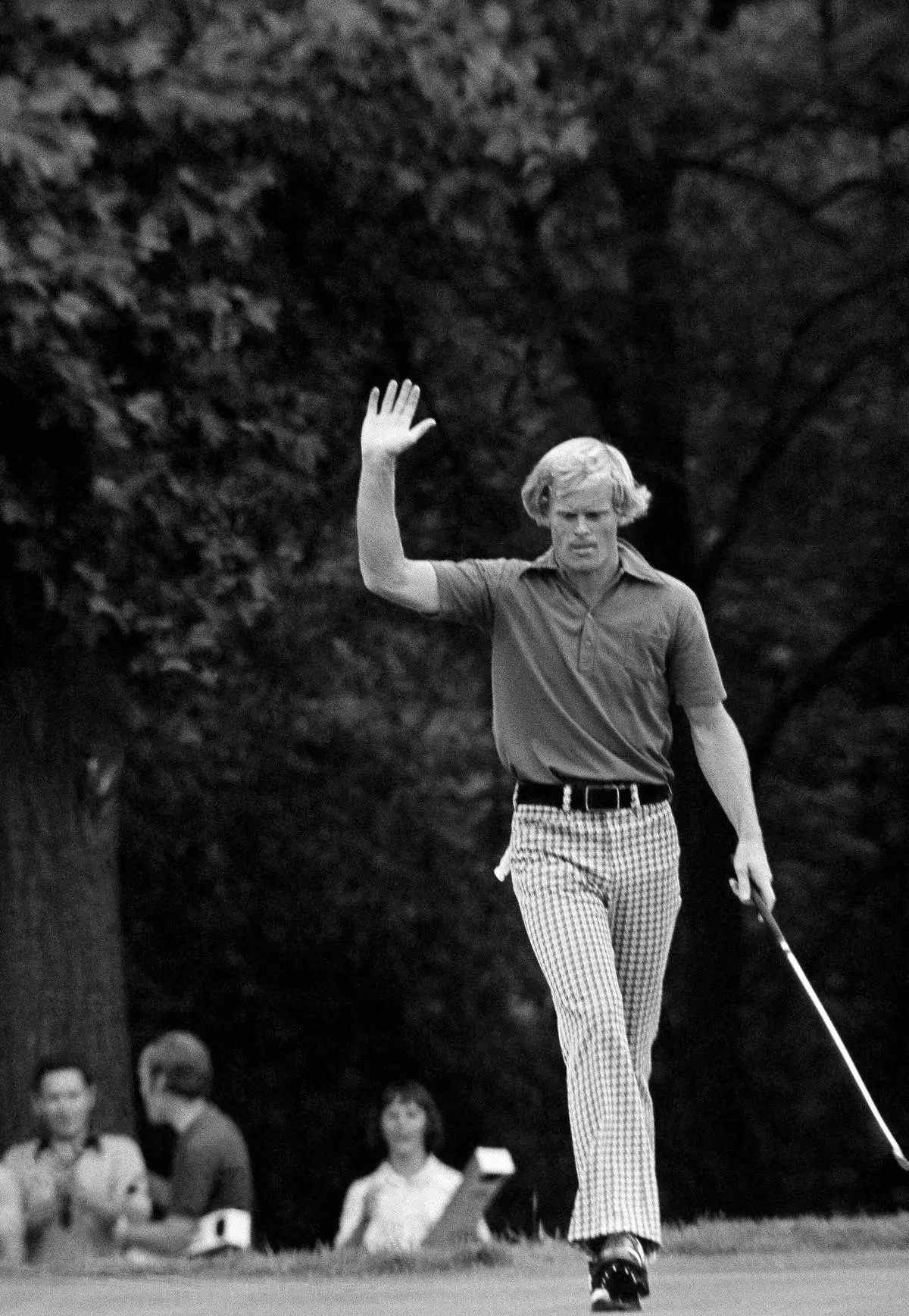

Jack Nicklaus, who added trees to the 13th hole at Muirfield Village after seeing players fly a fairway bunker on the left for a clear look at the green, said he’s OK with tree removal “if they take them down for a reason.”

“Why take a beautiful, gorgeous tree down?” he said. “Like Oakmont, for example. What’s the name of it? Oak. Mont. What’s that mean? Oaks on a mountain, sort of. And then they take them all down. I don’t like it.”

A lot of Oakmont’s members weren’t fans, either, which is why this project began under dark of night. The golf course in the 1990s was barely recognizable when set against pictures taken shortly after it opened in 1903.

Architect Henry Fownes had set out to build a links-style course. Dampening the noise and view of the Pennsylvania Turnpike, which bisects the layout, was one reason thousands of trees were planted in the 1960s and ’70s.

“We were finding that those little trees had all grown up and they were now hanging over some bunkers,” R. Banks-Smith, the chairman of Oakmont’s grounds committee when the project began, said in a 2007 interview. “And once you put a tree on either side of a bunker, you lose your bunker. So, you have to make a decision. Do you want bunkers or do you want trees?”

Oakmont went with bunkers – its renowned Church Pew Bunker between the third and fourth fairways might be the most famous in the world – and thus began a tree project that divides people as much today as it did when it started.

“I’m not always the biggest fan of mass tree removal,” Scott said. “I feel a lot of courses that aren’t links courses get framed nicely with trees, not like you’re opening it up to go play way over there.”

Too many trees, though, can pose risks.

Overgrown tree roots and too much shade provide competition for the tender grasses beneath. They hog up oxygen and sunlight and make the turf hard to maintain. They overhang fairways and bunkers and turn some shots envisioned by course architects into something completely different.

They also can be downright dangerous. In 2023 during the second round of the Masters, strong winds toppled three towering pine trees on the 17th hole, luckily missing fans who were there watching the action.

“There are lots of benefits that trees provide, but only in the right place,” said John Fech, the certified arborist at University of Nebraska who consults with the Golf Course Superintendents Association of America.

When Oakmont decided they didn’t want them at all, many great courses followed. Winged Foot, Medinah, Baltusrol and Merion are among those that have undergone removal programs.

Five years ago, Bryson DeChambeau overpowered Winged Foot, which had removed about 300 trees, simply by hitting the ball as far as he could, then taking his chances from the rough.

It’s the sort of golf Scheffler seems to be growing tired of: “When you host a championship tournament, if there’s no trees, you just hit it wherever you want, because if I miss a fairway by 10 yards, I’m in the thick rough (but) if I miss by 20, I’m in the crowd," Scheffler told Horvat.

How well that critique applies to Oakmont will be seen this week.

AP Golf Writer Doug Ferguson contributed.

AP golf: https://apnews.com/hub/golf

FILE - Johnny Miller, of Hilton Head Island S.C., who started his final Open round Sunday, June 17, 1973 six strokes behind the leaders and 3-over par 216, takes over fourth round lead with a charging 5-under par by birdie on the 15th, where he raises his hand after sinking the putt in Oakmont, Pa. (AP Photo, file)

FILE - Jack Nicklaus reacts on the first green during the playoff for the National Open Golf Tournament in Oakmont, Penn., June 17, 1962, against Arnold Palmer. (AP Photo/Preston Stroup, file)

FILE - This is the tenth green at Oakmont Country Club in Oakmont, Pa., Monday, Sept. 16, 2024, the course for the 2025 U.S. Open golf tournament. (AP Photo/Gene J. Puskar, File)

FILE - Arnold Palmer, left, swings his club as he and Julius Boros walk on to green at Oakmont Country Club at Oakmont, Penn., where they were in a four-way tie for the lead in the end of third round of the U.S. Open Golf Championship, June 16, 1973. Palmer, Boros, Jerry Hear and John Schlee all had 3 under 210. (AP Photo/File)

FILE - This is an overall photo of Oakmont Country Club in Oakmont, Pa., Monday, Sept. 16, 2024, the course for the 2025 U.S. Open golf tournament. (AP Photo/Gene J. Puskar, File)