Texas’ catastrophic flooding hit faith-based summer camps especially hard, and the heartbreak is sweeping across the country where similar camps mark a rite of passage and a crucial faith experience for millions of children and teens.

“Camp is such a unique experience that you just instantly empathize,” said Rachael Botting of the tragedy that struck Camp Mystic, the century-old all-girls Christian summer camp where at least 27 people were killed. A search was underway for more than 160 missing people in the area filled with youth camps as the overall death toll passed 100 on Tuesday.

Botting, a former Christian camp counselor, is a Wheaton College expert on the role camp plays in young people’s faith formation. “I do plan to send my boys to Christian summer camps. It is a nonnegotiable for us,” added the mother of three children under 4.

Generations of parents and children have felt the same about the approximately 3,000 faith-based summer camps across the country.

That is because for many campers, and young camp counselors, they are crucial independence milestones — the first time away from family or with a job away from home, said Robert Lubeznik-Warner, a University of Utah youth development researcher.

Experts say camps offer the opportunity to try skills and social situations for the first time while developing a stronger sense of self — and to do so in the safety of communities sharing the same values.

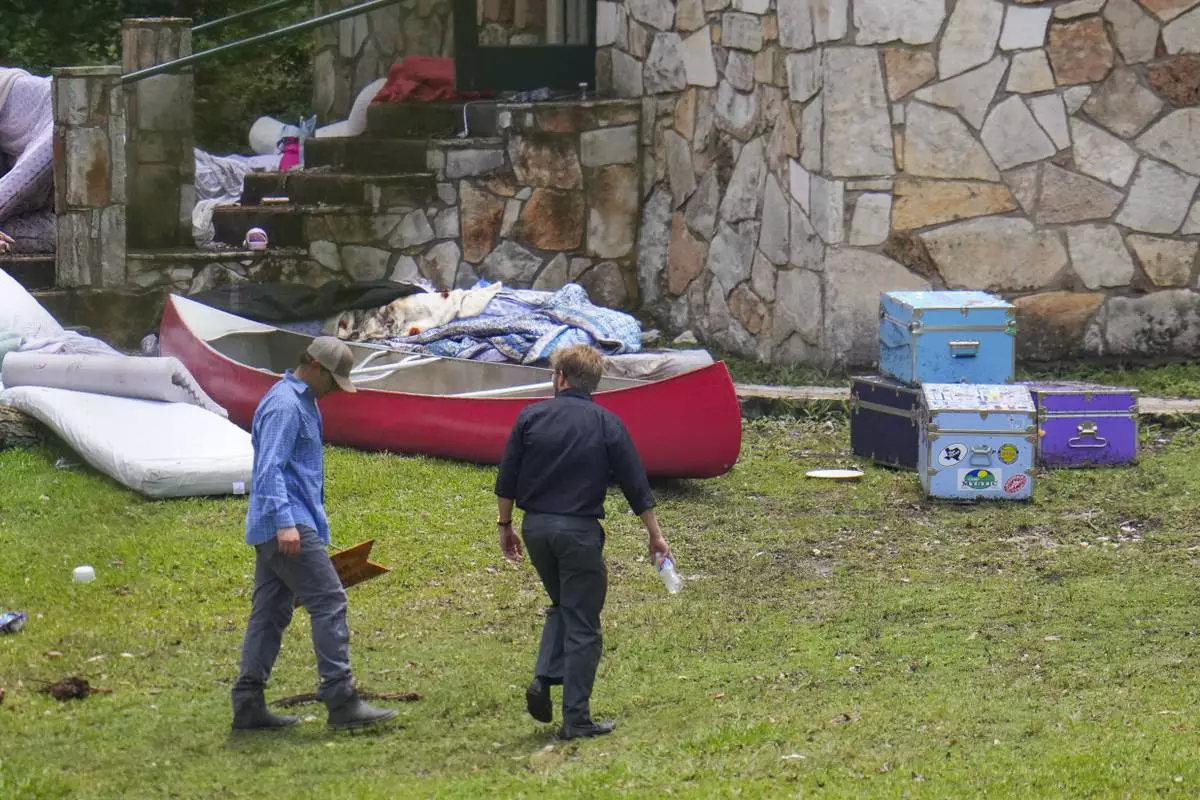

After the floodwaters rampaged through Camp Mystic, authorities and families have been combing through the wreckage strewed between the cabins and the riverbank.

On Sunday, a man there carried a wood sign similar to those seen hanging outside the door of several buildings. It read: “Do Good. Do No Harm. Keep Falling In Love With Jesus."

For generations, these Texas campers have been challenged to master quintessential summer activities from crafts to swimming while also growing in spiritual practices. Campers and counselors shared devotionals after breakfast, before bed and on Sunday mornings along the banks of the Guadalupe River, according to Camp Mystic’s brochure and website. They sang songs, listened to Scripture and attended Bible studies, too.

How big of a role faith has in the camp experience varies, Botting said. There are Christian camps where even canoeing outings are discussed as metaphors for spiritual journeys, others that aim to insert more religious activities like reading the Bible into children’s routines, and some that simply seek to give people a chance to encounter Jesus.

The religious emphasis also varies at Jewish camps, which span traditions from Orthodox to Reform. Activities range from daily Torah readings to yoga, said Jamie Simon, who leads the Foundation for Jewish Camp. The group supports 300 camps across North America, with about 200,000 young people involved this summer alone.

What they all have in common is a focus on building self-esteem as well as positive Jewish communities and identities — all particularly important as many struggle with antisemitism as well as the loneliness and mental health barriers common across all youth, Simon said.

At Seneca Hills Bible Camp and Retreat Center in Pennsylvania, there is archery, basketball and volleyball for summer campers, but also daily chapel, listening to missionaries and taking part in Bible study or hearing a Bible story depending on their age, which ranges from 5 to 18-year-olds.

“There’s a whole host of activities, but really the focus for camp is building relationships with one another and encouraging the kids’ relationships with God,” said camp executive director Lindon Fowler.

For many, participating in the same summer camp is also a generational tradition. Children are sent to the same place as their parents and grandparents to be around people who share the same value system in ways they can’t often experience in their local communities.

Because of their emphasis on independence and spending time away from family, summer camps in general have been especially popular in North America, Lubeznik-Warner said.

In the United States, faith-based summer camps date back to two parallel movements in the 19th century — the revivalist religious gatherings in tents and the “fresh-air movement” after the industrial revolution — and boomed after World War II, Botting said.

Particularly since the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns, as questions about children’s dependence on technology have surged, interest has grown in summer camps as “places where kids can really unplug, where kids can be kids,” Botting said.

Many parents like that camp can disconnect their children from their devices.

“We’re interested in campers hearing similar messages that they’re going to get at home or in their church or their faith communities,” Fowler said. He added: “I think they can hear … the meaning of things more clearly while they’re at camp" and away from distractions.

For Rob Ribbe, who teaches outdoors leadership at Wheaton College’s divinity school, all the elements of camp have biblical resonance.

“God uses times away, in community, often in creation … as a way to shape and form us, and help us to know him,” Ribbe said.

There are faith-related challenges, too. As children explore their identities and establish bonds outside their families, many programs have been wrestling with how to strike a balance between holding on to their denominations’ teachings while remaining welcoming, especially on issues of gender and sexuality, Botting said.

Rising costs are also a pressing issue. Historically, camps have been particularly popular among middle to upper-income families who can afford fees in the thousands of dollars for residential camps.

And then there is safety — whether in terms of potential abuse, with many church denominations marred by recent scandals, or the inherent risks of the outdoors. In Texas’ case, controversy is mounting over preparedness and official alerts for the natural disaster.

Every summer, hundreds of thousands of parents trust Brad Barnett and his team to keep their children safe — physically and spiritually — at the dozens of summer camps run by Lifeway Christian Resources.

Barnett, director of camp ministry, said already his staff has shared personal connections to Camp Mystic: One staff member’s daughter was an alum; another’s went to the same day camp with a girl who died in the flood; and a former staff member taught at the high school of a counselor who died.

But the tragedy is also informing their work as they provide yet another week of Christian summer camp experiences for children across the country.

“That’s the punch in the gut for us,” he said. “We know that there’s an implicit promise that we’re going to keep your kid safe, and so to not be able to deliver on that and the loss of life, it’s just so tragic and felt by so many.”

Experts say camp staff are likely to double down on best practices to respond to emergencies and keep their campers safe in the aftermath of the Texas floods.

“It’s, truly, truly heartbreaking for the whole community of Christian camping,” said Gregg Hunter, president of Christian Camp and Conference Association, which serves about 850 member camps catering to about 7 million campers a year.

But the positive and often lifelong impacts on children’s confidence and faith identity are so powerful that many leaders expressed hope the tragedy wouldn’t discourage children from trying it.

“It’s where my life took a dramatic turn from being a young, obnoxious, rebellious teenager,” Hunter said. “My camp experience introduced me to so many things, including to my faith, an opportunity, an option to enter into a relationship with God.”

Simon, a former camper and camp leader, said she is happy her son is currently at camp — even though there is a river by it.

“I wouldn’t want him to be anywhere else,” she said.

Associated Press writers Jim Vertuno and Holly Meyer contributed.

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

A person carries a sign reading "Do Good. Do No Harm. Keep Falling In Love with Jesus" after it was salvaged from debris washed up near Camp Mystic along the Guadalupe River after a flash flood on Friday swept through the area, Sunday, July 6, 2025, in Hunt, Texas. (AP Photo/Julio Cortez)

A person carries a sign reading "Do Good. Do No Harm. Keep Falling In Love with Jesus" after it was salvaged from debris washed up near Camp Mystic along the Guadalupe River after a flash flood on Friday swept through the area, Sunday, July 6, 2025, in Hunt, Texas. (AP Photo/Julio Cortez)