The UK government is teeing up some serious changes to its extradition arrangements with Hong Kong, setting Westminster abuzz. Conservative MP Alicia Kearns spilled the beans on July 24, revealing the government’s moves to amend the Extradition Act 2003. The plan? To set up a new, “case-by-case” review system for extradition requests from Hong Kong, effectively nudging open the door that’s been firmly shut since 2020.

Kearns was quick to sound the usual alarm, warning this could put Hong Kong critics and democracy activists currently living in Britain at risk. She didn’t mince words about the ongoing cross-border repression and called out the government for skating over the harsh realities facing Hongkongers in the UK. Human rights groups have slammed the proposed changes as reckless—and a betrayal of thousands who looked to Britain for protection and a fresh start.

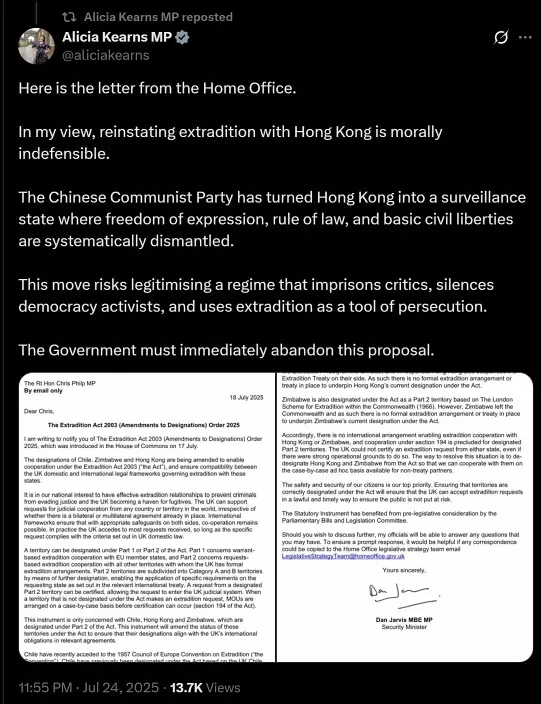

Kearns takes her case public—shares letters with Dan Jarvis over extradition plans on X.

Jarvis’s Denials and “Legalese” Loopholes

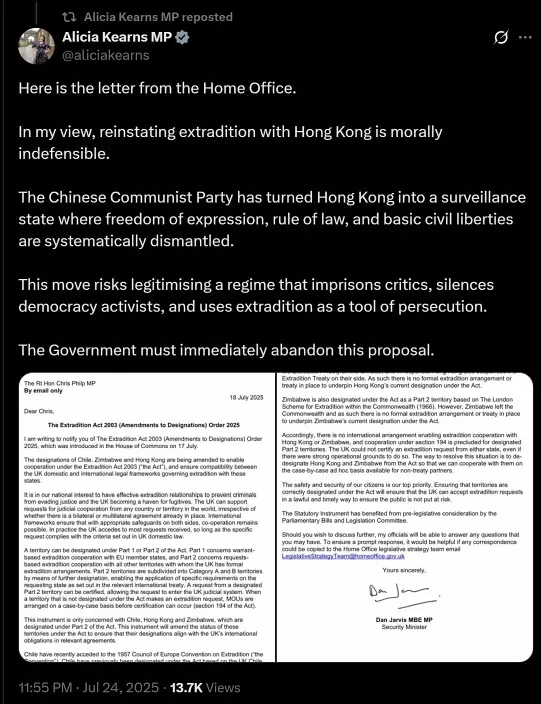

Security Minister Dan Jarvis fired back, insisting that the 1997 extradition treaty is still suspended and that these tweaks are simply giving legal legs to that break. In his words: “it is entirely incorrect to say the UK is resuming extradition cooperation with Hong Kong.” But opponents are sniffing out a classic bit of political hair-splitting, arguing that allowing any “case-by-case” reviews could quietly open the floodgates. Jarvis insists the move just severs formal ties, emphasizing Britain’s supposed ironclad commitment to the rule of law and the protection of all UK residents.

Jarvis pushes back, calling talk of resumed Hong Kong extraditions a “technical misread.”

The Bigger Geopolitical Game

So why now? Since Labour took the reins, London has been keen on smoothing things over with Beijing, hoping to grease the wheels for trade and cooperation. That’s a marked shift from the previous Conservative government’s frosty posture on China. Some political insiders say this “case-by-case” approach is a face-saving win-win: it eases diplomatic headaches with China and lets the government target “unwelcome individuals” for removal if needed—handy if you’re trying to balance trade talks with domestic politics.

But for Hongkongers and “pro-democracy” exiles, there’s real anxiety. The prospect of being sent back on “case-by-case,” even if only after a legal review, dangles the threat of becoming mere pawns in the high-stakes diplomatic tussle between Westminster and Beijing.

Justice or Just Optics?

This move doesn’t fully restore the old extradition treaty. Instead, it demotes Hong Kong’s legal status to that of “non-treaty” countries—think North Korea. Any extradition bid from Hong Kong would still need the green light from British courts, which can firmly block a surrender if there’s political motivation or a risk to human rights. Parliament also gets to keep an eye on the list of designated countries, ensuring nothing slips too far out of line with UK and international law. But for critics, none of that erases the chill running through the activist community.

Ariel

** The blog article is the sole responsibility of the author and does not represent the position of our company. **

Police smash a hidden plot. On December 11 and 12, the National Security Department rounded up nine local men running secret military-style training in dingy industrial units. Some had even shown up at the Tai Po Wang Fuk Court fire scene decked out in black-clad riot gear, itching for chaos.

Hong Kong cops pull no punches. National Security chief superintendent Li Kwai-wah announces the first-ever bust under Section 13 of the Safeguarding National Security Ordinance—illegal drilling. That means offering or joining weapon drills, military exercises, or tactical formations without proper approval. Once convicted, defendants face up to seven years behind bars. Worse if foreign forces pull the strings: 10 years max.

Guns, Bombs, and Terror Vibes

The Insider spots the real red flags here. These aren't weekend warriors—they're diving into firearms training and bomb-making.

First, as Security Secretary Chris Tang Ping-keung points out: forget the label, judge the poison—offensive weapons, military maneuvers, formation drills. Cops seize homemade explosives with fuses primed to blow, plus 3D printers churning out gun parts. This screams bomb plots and crime sprees, way beyond "training." Alarming is an understatement.

Police keep dismantling these nightmares. They've cracked explosives and firearms rings, gutted terror cells. This bust screams terrorism brewing—like the judge in the Caritas Medical Centre bomb plot warned: a straight-up war on society.

Second, some of these guys were spotted at the Tai Po blaze.

Intelligence paints a grim picture. Some arrestees lurked at Tai Po's Wang Fuk Court fire in classic 2019 anti-extradition garb. One suspect brags about using his new skills—fighting, guns, knives—to target cops and officials if riots reignite. Others trash the government online for "lousy relief," fanning hate against the SAR.

These aren't new faces. Some rioted multiple times in 2019's anti-extradition mess. Take Mr. Li: he ran a Telegram hate group plotting petrol bombs, guns, even a "massacre." Jailed 29 months for sedition and wounding conspiracy.

Out on parole by late 2024, still under supervision—one kept linking up and drilling illegally. No surprise—the Office for Safeguarding National Security called it: ulterior motives stir in crises, spewing lies to wreck relief efforts.

Foreign Shadows Loom Large?

Moreover, whether foreign funding is involved.

The Hong Kong Police Force stayed on the hunt. They'll track these plotters, make more arrests if needed. Top probe: involvement of foreign forces and money? The law slams extra time for that meddling.

History repeats. Police had already nailed three from the banned “Hong Kong Democratic Independence Union” for secession conspiracy. Fugitive founder Keung Ka-wai built a fake "army," trained recruits for "Hong Kong independence." One kid defendant of just 15, suckered into jail.

These overseas fugitives won't quit. They spew rhetoric, lure HongKong youth into the trap, biding time for "resistance." SAR government banned “Hong Kong Parliament” and the “Hong Kong Democratic Independence Union”: starves their funds, warns everyone: don't get poisoned and snared.

Bottom line: Hong Kong looks calm, but radicals churn below the surface. Stay sharp, and beware of those hell-bent on shattering the peace.