PERRY, N.Y. (AP) — As a student in western New York's rural Wyoming County, Briar Townes honed an artistic streak that he hopes to make a living from one day. In high school, he clicked with a college-level drawing and painting class.

But despite the college credits he earned, college isn't part of his plan.

Click to Gallery

Devon Wells, a junior at Perry Central High School, walks across Halo Farms, where he works, on March 12, 2025, in Perry, N.Y. (AP Photo/Lauren Petracca)

Devon Wells, a junior at Perry Central High School, poses for a portrait in a cowshed at Halo Farms, where he works, on March 12, 2025, in Perry, N.Y. (AP Photo/Lauren Petracca)

Briar Townes, a senior at Perry Central High School, straightens a piece of his art on display at the Arts Council for Wyoming County, on March 12, 2025, in Perry, N.Y. (AP Photo/Lauren Petracca)

Briar Townes, a senior at Perry Central High School, poses for a portrait inside the Arts Council for Wyoming County, where he has art displayed as part of an All-County High School Arts Show, on March 12, 2025, in Perry, N.Y. (AP Photo/Lauren Petracca)

Devon Wells, a junior at Perry Central High School, welds a metal calf feeder at Halo Farms, where he works, on March 12, 2025, in Perry, N.Y. (AP Photo/Lauren Petracca)

Since graduating from high school in June, he has been overseeing an art camp at the county's Arts Council. If that doesn't turn into a permanent job, there is work at Creative Food Ingredients, known as the “cookie factory” for the way it makes the town smell like baking cookies, or at local factories like American Classic Outfitters, which designs and sews athletic uniforms.

“My stress is picking an option, not finding an option,” he said.

Even though rural students graduate from high school at higher rates than their peers in cities and suburbs, fewer of them go on to college.

Many rural school districts, including the one in Perry that Townes attends, have begun offering college-level courses and working to remove academic and financial obstacles to higher education, with some success. But college doesn't hold the same appeal for students in rural areas where they often would need to travel farther for school, parents have less college experience themselves, and some of the loudest political voices are skeptical of the need for higher education.

College enrollment for rural students has remained largely flat in recent years, despite the district-level efforts and stepped-up recruitment by many universities. About 55% of rural U.S. high school students who graduated in 2023 enrolled in college, according to National Clearinghouse Research Center data. That's compared to 64% of suburban graduates and 59% of urban graduates.

College can make a huge difference in earning potential. An American man with a bachelor’s degree earns an estimated $900,000 more over his lifetime than a peer with a high school diploma, research by the Social Security Administration has found. For women, the difference is about $630,000.

A lack of a college degree is no obstacle to opportunity in places such as Wyoming County, where people like to say there are more cows than people. The dairy farms, potato fields and maple sugar houses are a source of identity and jobs for the county just east of Buffalo.

“College has never really been, I don’t know, a necessity or problem in my family,” said Townes, the middle of three children whose father has a tattoo shop in Perry.

At Perry High School, Superintendent Daryl McLaughlin said the district takes cues from students like Townes, their families and the community, supplementing college offerings with programs geared toward career and technical fields such as the building trades. He said he is as happy to provide reference checks for employers and the military as he is to write recommendations for college applications.

“We’re letting our students know these institutions, whether it is a college or whether employers, they’re competing for you,” he said. “Our job is now setting them up for success so that they can take the greatest advantage of that competition, ultimately, to improve their quality of life.”

Still, college enrollment in the district has exceeded the national average in recent years, going from 60% of the class of 2022’s 55 graduates to 67% of 2024's and 56% of 2025's graduates. The district points to a decision to direct federal pandemic relief money toward covering tuition for students in its Accelerated College Enrollment program — a partnership with Genesee Community College. When the federal money ran out, the district paid to keep it going.

“This is a program that’s been in our community for quite some time, and it’s a program our community supports,” McLaughlin said.

About 15% of rural U.S. high school students were enrolled in college classes in January 2025 through such dual enrollment arrangements, a slightly lower rate than urban and suburban students, an Education Department survey found.

Rural access to dual enrollment is a growing area of focus as advocates seek to close gaps in access to higher education. The College in High School Alliance this year announced funding for seven states to develop policy to expand programs for rural students.

Around the country, many students feel jaded by the high costs of college tuition. And Americans are increasingly skeptical about the value of college, polls have shown, with Republicans, the dominant party in rural America, losing confidence in higher education at higher rates than Democrats.

“Whenever you have this narrative that ‘college is bad, college is bad, these professors are going to indoctrinate you,’ it’s hard,” said Andrew Koricich, executive director of the Alliance for Research on Regional Colleges at Appalachian State University in North Carolina. “You have to figure out, how do you crack through that information ecosphere and say, actually, people with a bachelor’s degree, on average, earn 65% more than people with a high school diploma only?”

In much of rural America, about 21% of people over the age of 25 have a bachelor’s degree, compared to about 36% of adults in other areas, according to a government analysis of U.S. Census findings.

In rural Putnam County, Florida, about 14% of adults have a bachelor’s degree. That doesn't stop principal Joe Theobold from setting and meeting an annual goal of 100% college admission for students at Q.I. Roberts Jr.-Sr. High School.

Paper mills and power plants provide opportunities for a middle class life in the county, where the cost of living is low. But Theobold tells students the goal of higher education “is to go off and learn more about not only the world, but also about yourself.”

“You don’t want to be 17 years old, determining what you’re going to do for the rest of your life,” he said.

Families choose the magnet school because of its focus on higher education, even though most of the district’s parents never went to a college. Many students visit college campuses through Camp Osprey, a University of North Florida program that helps students experience college dorms and dining halls.

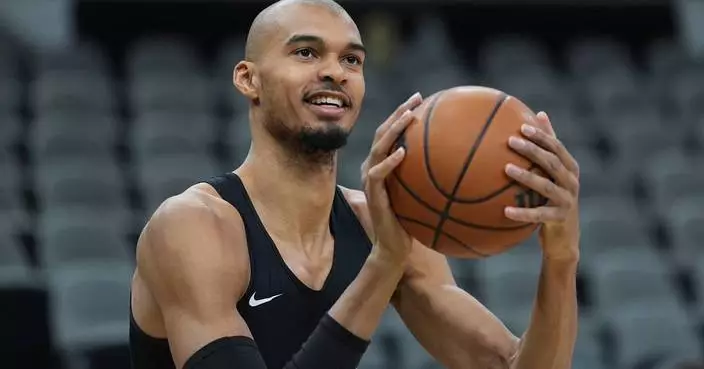

In upstate New York, high school junior Devon Wells grew up on his family farm in Perry but doesn't see his future there. He's considering a career in welding, or as an electrical line worker in South Carolina, where he heard the pay might be double what he would make at home. None of his plans require college, he said.

“I grew up on a farm, so that’s all hands-on work. That’s really all I know and would want to do,” Devon said.

Neither his nor Townes’ parents have pushed one way or the other, they said.

“I remember them talking to me like, `Hey, would you want to go to college?’ I remember telling them, 'not really,’” Townes said. He would have listened if a college recruiter reached out, he said, but wouldn’t be willing to move very far.

The Associated Press’ education coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

Devon Wells, a junior at Perry Central High School, walks across Halo Farms, where he works, on March 12, 2025, in Perry, N.Y. (AP Photo/Lauren Petracca)

Devon Wells, a junior at Perry Central High School, poses for a portrait in a cowshed at Halo Farms, where he works, on March 12, 2025, in Perry, N.Y. (AP Photo/Lauren Petracca)

Briar Townes, a senior at Perry Central High School, straightens a piece of his art on display at the Arts Council for Wyoming County, on March 12, 2025, in Perry, N.Y. (AP Photo/Lauren Petracca)

Briar Townes, a senior at Perry Central High School, poses for a portrait inside the Arts Council for Wyoming County, where he has art displayed as part of an All-County High School Arts Show, on March 12, 2025, in Perry, N.Y. (AP Photo/Lauren Petracca)

Devon Wells, a junior at Perry Central High School, welds a metal calf feeder at Halo Farms, where he works, on March 12, 2025, in Perry, N.Y. (AP Photo/Lauren Petracca)

ATLANTA (AP) — Donald Trump would not be the first president to invoke the Insurrection Act, as he has threatened, so that he can send U.S. military forces to Minnesota.

But he'd be the only commander in chief to use the 19th-century law to send troops to quell protests that started because of federal officers the president already has sent to the area — one of whom shot and killed a U.S. citizen.

The law, which allows presidents to use the military domestically, has been invoked on more than two dozen occasions — but rarely since the 20th Century's Civil Rights Movement.

Federal forces typically are called to quell widespread violence that has broken out on the local level — before Washington's involvement and when local authorities ask for help. When presidents acted without local requests, it was usually to enforce the rights of individuals who were being threatened or not protected by state and local governments. A third scenario is an outright insurrection — like the Confederacy during the Civil War.

Experts in constitutional and military law say none of that clearly applies in Minneapolis.

“This would be a flagrant abuse of the Insurrection Act in a way that we've never seen,” said Joseph Nunn, an attorney at the Brennan Center for Justice's Liberty and National Security Program. “None of the criteria have been met.”

William Banks, a Syracuse University professor emeritus who has written extensively on the domestic use of the military, said the situation is “a historical outlier” because the violence Trump wants to end “is being created by the federal civilian officers” he sent there.

But he also cautioned Minnesota officials would have “a tough argument to win” in court, because the judiciary is hesitant to challenge “because the courts are typically going to defer to the president” on his military decisions.

Here is a look at the law, how it's been used and comparisons to Minneapolis.

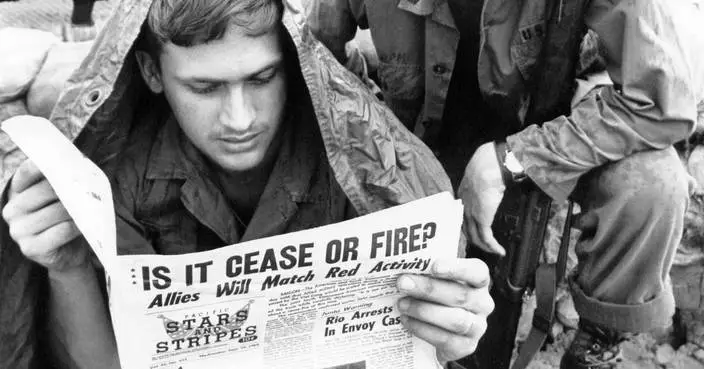

George Washington signed the first version in 1792, authorizing him to mobilize state militias — National Guard forerunners — when “laws of the United States shall be opposed, or the execution thereof obstructed.”

He and John Adams used it to quash citizen uprisings against taxes, including liquor levies and property taxes that were deemed essential to the young republic's survival.

Congress expanded the law in 1807, restating presidential authority to counter “insurrection or obstruction” of laws. Nunn said the early statutes recognized a fundamental “Anglo-American tradition against military intervention in civilian affairs” except “as a tool of last resort.”

The president argues Minnesota officials and citizens are impeding U.S. law by protesting his agenda and the presence of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers and Customs and Border Protection officers. Yet early statutes also defined circumstances for the law as unrest “too powerful to be suppressed by the ordinary course” of law enforcement.

There are between 2,000 and 3,000 federal authorities in the Minneapolis-St. Paul metro area, compared to Minneapolis, which has fewer than 600 police officers. Protesters' and bystanders' video, meanwhile, has shown violence initiated by federal officers, with the interactions growing more frequent since Renee Good was shot three times and killed.

“ICE has the legal authority to enforce federal immigration laws,” Nunn said. “But what they're doing is a sort of lawless, violent behavior” that goes beyond their legal function and “foments the situation” Trump wants to suppress.

“They can't intentionally create a crisis, then turn around to do a crackdown,” he said, adding that the Constitutional requirement for a president to “faithfully execute the laws” means Trump must wield his power, on immigration and the Insurrection Act, “in good faith.”

Courts have blocked some of Trump's efforts to deploy the National Guard, but he'd argue with the Insurrection Act that he does not need a state's permission to send troops.

That traces to President Abraham Lincoln, who held in 1861 that Southern states could not legitimately secede. So, he convinced Congress to give him express power to deploy U.S. troops, without asking, into Confederate states he contended were still in the Union. Quite literally, Lincoln used the act as a legal basis to fight the Civil War.

Nunn said situations beyond such a clear insurrection as the Confederacy still require a local request or another trigger that Congress added after the Civil War: protecting individual rights. Ulysses S. Grant used that provision to send troops to counter the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacists who ignored the 14th and 15th amendments and civil rights statutes.

During post-war industrialization, violence erupted around strikes and expanding immigration — and governors sought help.

President Rutherford B. Hayes granted state requests during the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 after striking workers, state forces and local police clashed, leading to dozens of deaths. Grover Cleveland granted a Washington state governor's request — at that time it was a U.S. territory — to help protect Chinese citizens who were being attacked by white rioters. President Woodrow Wilson sent troops to Colorado in 1914 amid a coal strike after workers were killed.

Federal troops helped diffuse each situation.

Banks stressed that the law then and now presumes that federal resources are needed only when state and local authorities are overwhelmed — and Minnesota leaders say their cities would be stable and safe if Trump's feds left.

As Grant had done, mid-20th century presidents used the act to counter white supremacists.

Franklin Roosevelt dispatched 6,000 troops to Detroit — more than double the U.S. forces in Minneapolis — after race riots that started with whites attacking Black residents. State officials asked for FDR's aid after riots escalated, in part, Nunn said, because white local law enforcement joined in violence against Black residents. Federal troops calmed the city after dozens of deaths, including 17 Black residents killed by local police.

Once the Civil Rights Movement began, presidents sent authorities to Southern states without requests or permission, because local authorities defied U.S. civil rights law and fomented violence themselves.

Dwight Eisenhower enforced integration at Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas; John F. Kennedy sent troops to the University of Mississippi after riots over James Meredith's admission and then pre-emptively to ensure no violence upon George Wallace's “Stand in the Schoolhouse Door” to protest the University of Alabama's integration.

“There could have been significant loss of life from the rioters” in Mississippi, Nunn said.

Lyndon Johnson protected the 1965 Voting Rights March from Selma to Montgomery after Wallace's troopers attacked marchers' on their first peaceful attempt.

Johnson also sent troops to multiple U.S. cities in 1967 and 1968 after clashes between residents and police escalated. The same thing happened in Los Angeles in 1992, the last time the Insurrection Act was invoked.

Riots erupted after a jury failed to convict four white police officers of excessive use of force despite video showing them beating a Rodney King, a Black man. California Gov. Pete Wilson asked President George H.W. Bush for support.

Bush authorized about 4,000 troops — but after he had publicly expressed displeasure over the trial verdict. He promised to “restore order” yet directed the Justice Department to open a civil rights investigation, and two of the L.A. officers were later convicted in federal court.

President Donald Trump answers questions after signing a bill that returns whole milk to school cafeterias across the country, in the Oval Office of the White House, Wednesday, Jan. 14, 2026, in Washington. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon)