TALLINN, Estonia (AP) — YouTube videos that won't load. A visit to a popular independent media website that produces only a blank page. Cellphone internet connections that are down for hours or days.

Going online in Russia can be frustrating, complicated and even dangerous.

It's not a network glitch but a deliberate, multipronged and long-term effort by authorities to bring the internet under the Kremlin's full control. Authorities adopted restrictive laws and banned websites and platforms that won't comply. Technology has been perfected to monitor and manipulate online traffic.

While it's still possible to circumvent restrictions by using virtual private network apps, those are routinely blocked, too.

Authorities further restricted internet access this summer with widespread shutdowns of cellphone internet connections and adopting a law punishing users for searching for content they deem illicit.

They also are threatening to go after the popular WhatsApp platform while rolling out a new “national” messaging app that's widely expected to be heavily monitored.

President Vladimir Putin urged the government to “stifle” foreign internet services and ordered officials to assemble a list of platforms from “unfriendly” states that should be restricted.

Experts and rights advocates told The Associated Press that the scale and effectiveness of the restrictions are alarming. Authorities seem more adept at it now, compared with previous, largely futile efforts to restrict online activities, and they're edging closer to isolating the internet in Russia.

Human Rights Watch researcher Anastasiia Kruope describes Moscow’s approach to reining in the internet as “death by a thousand cuts."

"Bit by bit, you’re trying to come to a point where everything is controlled.”

Kremlin efforts to control what Russians do, read or say online dates to 2011-12, when the internet was used to challenge authority. Independent media outlets bloomed, and anti-government demonstrations that were coordinated online erupted after disputed parliamentary elections and Putin’s decision to run again for president.

Russia began adopting regulations tightening internet controls. Some blocked websites; others required providers to store call records and messages, sharing it with security services if needed, and install equipment allowing authorities to control and cut off traffic.

Companies like Google or Facebook were pressured to store user data on Russian servers, to no avail, and plans were announced for a “sovereign internet” that could be cut off from the rest of the world.

Russia’s popular Facebook-like social media platform VK, founded by Pavel Durov long before he launched the Telegram messaging app, came under the control of Kremlin-friendly companies. Russia tried to block Telegram between 2018-20 but failed.

Prosecutions for social media posts and comments became common, showing that authorities were closely watching the online space.

Still, experts had dismissed Kremlin efforts to rein in the internet as futile, arguing Russia was far from building something akin to China’s “Great Firewall,” which Beijing uses to block foreign websites.

After Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the government blocked major social media like Twitter, Facebook and Instagram, as well as Signal and a few other messaging apps. VPNs also were targeted, making it harder to reach restricted websites.

YouTube access was disrupted last summer in what experts called deliberate throttling by authorities. The Kremlin blamed YouTube owner Google for not maintaining its hardware in Russia. The platform has been wildly popular in Russia, both for entertainment and for voices critical of the Kremlin, like the late opposition leader Alexei Navalny.

Cloudflare, an internet infrastructure provider, said in June that websites using its services were being throttled in Russia. Independent news site Mediazona reported that several other popular Western hosting providers also are being inhibited.

Cyber lawyer Sarkis Darbinyan, founder of Russian internet freedom group Roskomsvoboda, said authorities have been trying to push businesses to migrate to Russian hosting providers that can be controlled.

He estimates about half of all Russian websites are powered by foreign hosting and infrastructure providers, many offering better quality and price than domestic equivalents. A “huge number” of global websites and platforms use those providers, he said, so cutting them off means those websites “automatically become inaccessible” in Russia too.

Another concerning trend is the consolidation of Russia’s internet providers and companies that manage IP addresses, according to a July 30 Human Rights Watch report.

Last year, authorities raised the cost of obtaining an internet provider license from 7,500 rubles (about $90) to 1 million rubles (over $12,300), and state data shows that more than half of all IP addresses in Russia are managed by seven large companies, with Rostelecom, Russia’s state telephone and internet giant, accounting for 25%.

The Kremlin is striving “to control the internet space in Russia, and to censor things, to manipulate the traffic,” said HRW's Kruope.

A new Russian law criminalized online searches for broadly defined “extremist” materials. That could include LGBTQ+ content, opposition groups, some songs by performers critical of the Kremlin — and Navalny's memoir, which was designated as extremist last week.

Right advocates say it's a step toward punishing consumers — not just providers — like in Belarus, where people are routinely fined or jailed for reading or following certain independent media outlets.

Stanislav Seleznev, cyber security expert and lawyer with the Net Freedom rights group, doesn’t expect ubiquitous prosecutions, since tracking individual online searches in a country of 146 million remains a tall order. But even a limited number of cases could scare many from restricted content, he said.

Another major step could be blocking WhatsApp, which monitoring service Mediascope said had over 97 million monthly users in April.

WhatsApp “should prepare to leave the Russian market,” said lawmaker Anton Gorelkin, and a new “national” messenger, MAX, developed by social media company VK, would take its place. Telegram probably won't be restricted, he said.

MAX, promoted as a one-stop shop for messaging, online government services, making payments and more, was rolled out for beta tests but has yet to attract a wide following. Over 2 million people registered by July, the Tass news agency reported.

Its terms and conditions say it will share user data with authorities upon request, and a new law stipulates its preinstallation in all smartphones sold in Russia. State institutions, officials and businesses are actively encouraged to move communications and blogs to MAX.

Anastasiya Zhyrmont of the Access Now digital rights group said both Telegram and WhatsApp were disrupted in Russia in July in what could be a test of how potential blockages would affect internet infrastructure.

It wouldn’t be uncommon. In recent years, authorities regularly tested cutting off the internet from the rest of the world, sometimes resulting in outages in some regions.

Darbinyan believes the only way to make people use MAX is to “shut down, stifle” every Western alternative. “But again, habits ... do not change in a year or two. And these habits acquired over decades, when the internet was fast and free,” he said.

Government media and internet regulator Roskomnadzor uses more sophisticated methods, analyzing all web traffic and identifying what it can block or choke off, Darbinyan said.

It's been helped by “years of perfecting the technology, years of taking over and understanding the architecture of the internet and the players,” as well as Western sanctions and companies leaving the Russian market since 2022, said Kruope of Human Rights Watch.

Russia is “not there yet” in isolating its internet from the rest of the world, Darbinyan said, but Kremlin efforts are “bringing it closer.”

In this photo released by the State Duma, deputies attend a session at the State Duma, the lower house of the Russian parliament, in Moscow, Russia, Tuesday, July 22, 2025. (The State Duma, Lower House of the Russian Parliament Press Service via AP)

Russian President Vladimir Putin speaks with Sberbank CEO German Gref during their meeting at the Kremlin in Moscow, Russia, Tuesday, July 29, 2025. (Mikhail Metzel, Sputnik, Kremlin Pool Photo via AP)

A woman wearing a niqab, checks her phone while walking along the Red Square in Moscow, Russia, Wednesday, July 30, 2025. (AP Photo/Pavel Bednyakov)

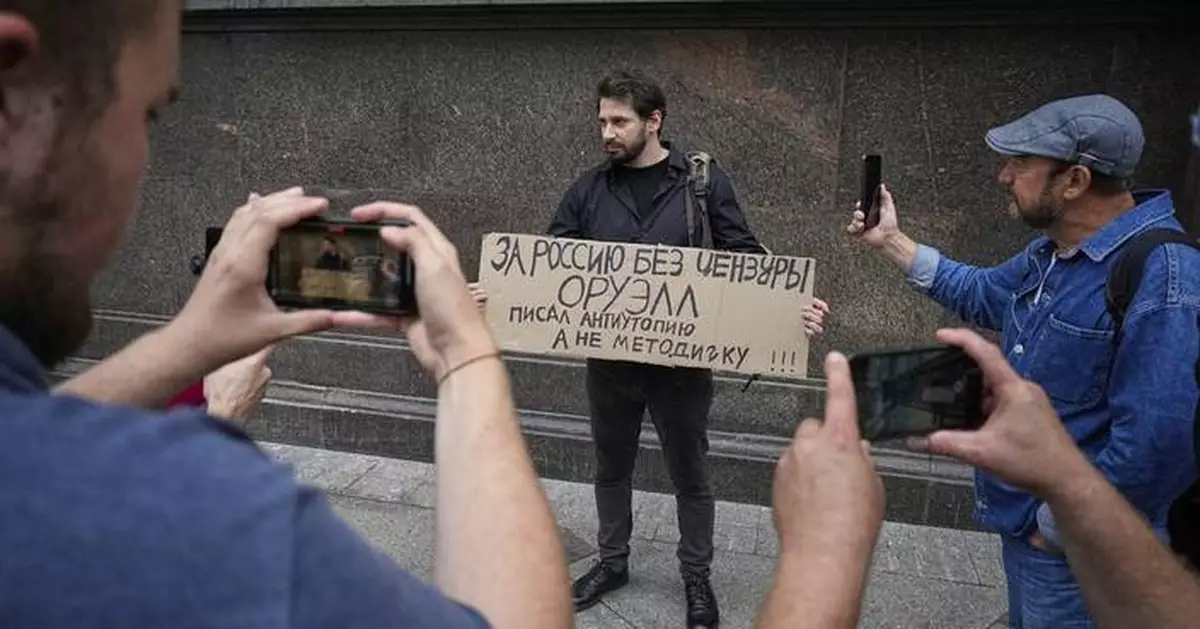

An activist holds a sign reading, "For Russia without censorship. Orwell wrote a dystopia, not an instruction manual,” referring to author George Orwell during a protest in front of the State Duma, the lower house of the Russian parliament, in Moscow, Russia, Tuesday, July 22, 2025, prior to lawmakers approving a measure that punishes online searches for information that is deemed “extremist.” (AP Photo)