NEW HAVEN, Conn. (AP) — Nestled on a narrow, one-way street among Yale University buildings, a pizza joint and an ice cream shop, Toad’s Place looks like a typical haunt for college kids.

But inside the modest, two-story building is a veritable museum of paintings and signed photos depicting the head-turning array of artists who've played the nightclub over the years:

Click to Gallery

Harmonica player Don DeStefano, right, plays with the band Creamery Station at Toad's Place in New Haven, Conn., on Friday, May 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Jessica Hill)

A poster of Jon Bon Jovi with the date he performed is displayed in the women's bathroom at Toad's Place in New Haven, Conn., on Friday, May 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Jessica Hill)

Brian Phelps, owner of Toad's Place, looks over newspaper clippings he has collected about the famous concert venue in New Haven, Conn., on Friday, May 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Jessica Hill)

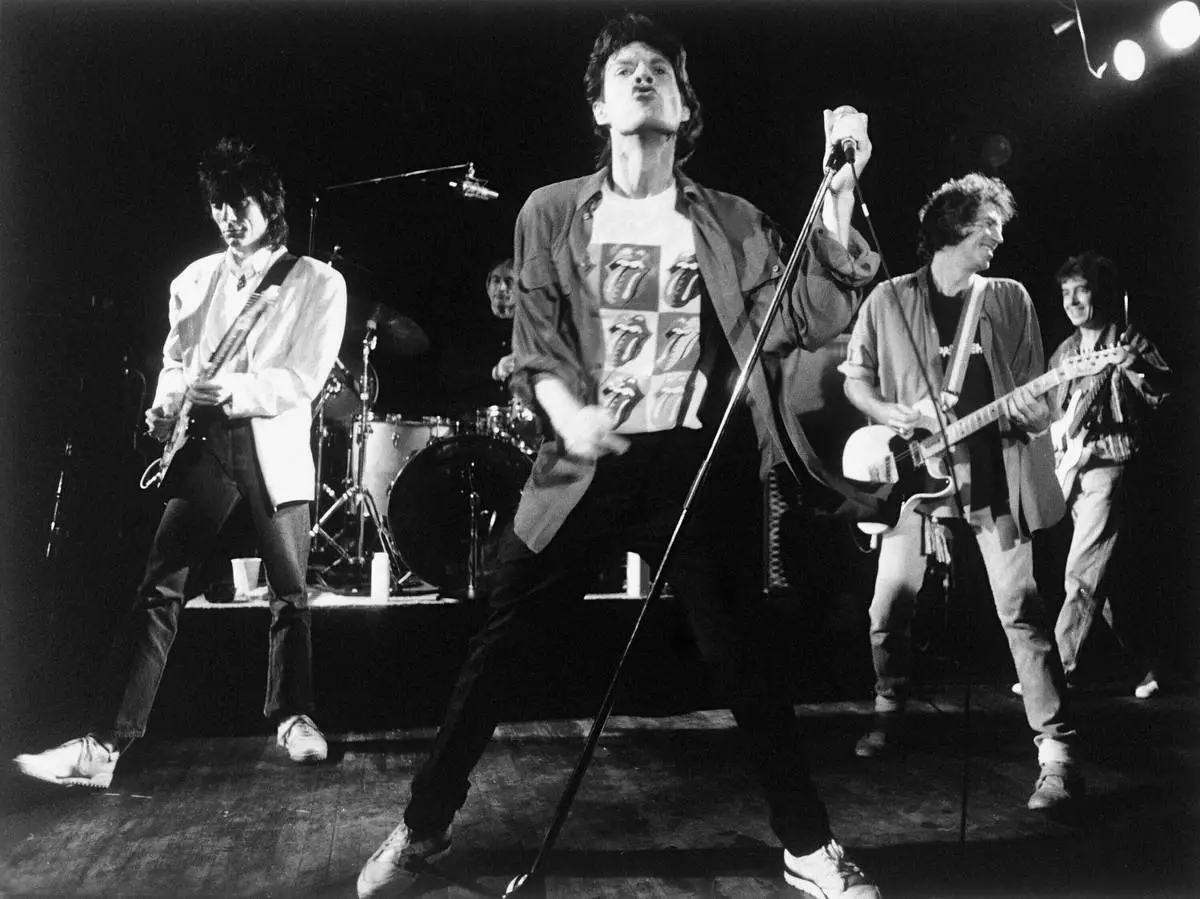

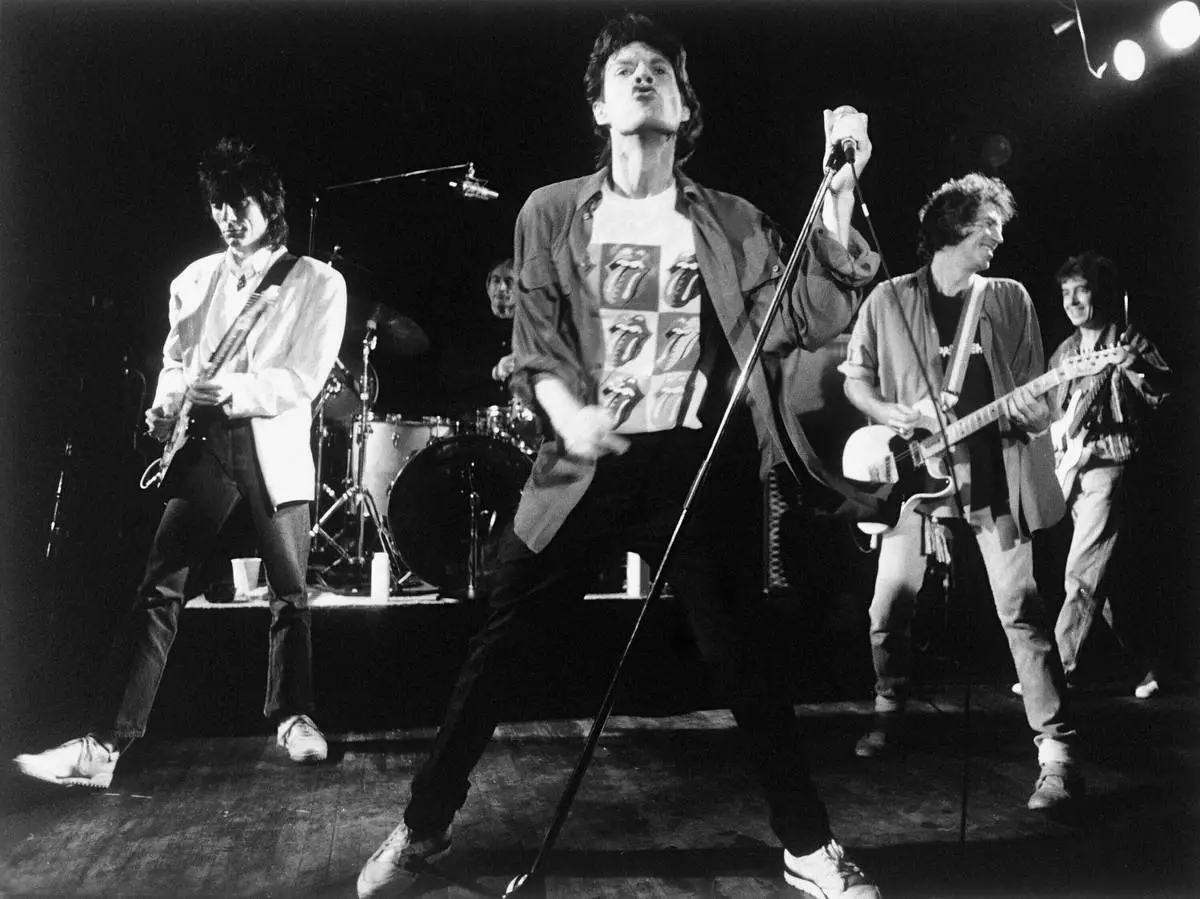

FILE - The Rolling Stones perform during an impromptu concert at the Toad's Place nightclub in New Haven, Conn., early Sunday, Aug. 13, 1989. (AP Photo/Dimo Safari, File)

A mural of past concerts at Toad's Place is displayed above one of the bars in New Haven, Conn., on Friday, May 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Jessica Hill)

The Rolling Stones. Bob Dylan. Billy Joel. Bruce Springsteen. U2. The Ramones and Johnny Cash. Rap stars Kendrick Lamar, Drake, Kanye West, Cardi B, Run-D.M.C., Snoop Dogg and Public Enemy. Blues legends B.B. King, Bo Diddley, Muddy Waters, Willie Dixon and John Lee Hooker. And jazz greats Count Basie, Dizzy Gillespie and Herbie Hancock.

This year, the New Haven institution is celebrating 50 years in business. And the people who made it happen are reflecting on Toad's success in attracting so many top acts to a venue with a standing-only capacity of about 1,000.

“You know, I thought it would be good for a few years and then I’d be out doing something else,” said owner Brian Phelps, 71, who started as the club’s manager in 1976. “And then the thing started to happen when some of the big bands started to come here.”

Original owner Mike Spoerndle initially opened Toad’s Place in January 1975 as a French restaurant with two friends he later bought out. Before that, the building had been a burger and sandwich joint.

But when the restaurant got off to a slow start, Spoerndle had an idea for bringing in more customers, especially students: music, dancing and beer. A Tuesday night promotion with bands and 25-cent brews helped turn the tide.

Among the acts who performed was New Haven-born Michael Bolotin, who would change his name to Michael Bolton and go on to become a Grammy-winning ballad writer and singer.

The gregarious and charismatic Spoerndle, who died in 2011, endeared himself to bands and customers. A local musician he tapped as Toad's booking agent used his connections to bring in area bands and, later, major blues acts.

Then, in 1977, came a crucial moment. Spoerndle met and befriended concert promoter Jim Koplik, who would bring in many big names to Toad's over the years, and still does today.

“Mike knew how to make a really great room and Brian knew how to really run a great room,” said Koplik, now president of Live Nation for Connecticut and upstate New York.

A year later, Springsteen stopped by Toad's to play with the Rhode Island band Beaver Brown after he finished a three-hour show at the nearby New Haven Coliseum.

In 1980, Billy Joel stunned Toad’s by picking it — and several other venues — to record songs for his first live album, “Songs in the Attic.”

That same year, a little-known band from Ireland would play at Toad’s as an opening act. It was among the first shows U2 played in North America. The band played the club two more times in 1981 before hitting it big.

On a Saturday night in August 1989, Toad’s advertised a performance by a local band, The Sons of Bob, and a celebration of Koplik’s 40th birthday, followed by a dance party.

The admission price: $3.01.

After The Sons of Bob did a half-hour set, Spoerndle and Koplik took the stage.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” Spoerndle said.

Koplik followed with, “Please welcome the Rolling Stones!”

The stunned crowd of around 700 erupted as the Stones kicked off an hourlong show with “Start Me Up.”

“Thank you. Good, good, good. We’ve been playing for ourselves the last six weeks,” Mick Jagger told the crowd.

The Stones had been practicing at a former school in Washington, Connecticut, for their upcoming “Steel Wheels” tour — their first in seven years — and had wanted to play a small club as a warmup. The band’s promoter called Koplik, who recommended Toad's. The band agreed, but insisted on secrecy.

Those at Toad’s kept a lid on it for the most part, but swirling rumors helped pack the club.

Doug Steinschneider, a local musician, was one of those at the venue that night after a friend told him the Stones would be playing. He wasn’t able to get in, but managed to get near a side door where he could see Jagger singing.

“It was amazing!” said Steinschneider. “For being a place where major bands show up, it’s a tiny venue. So you get to see the band in their real element. In other words, you’re not watching a screen.”

A few months later, Bob Dylan's manager reached out looking for a club where he could warm up for an upcoming tour.

Dylan's 1990 show at Toad's sold out in 18 minutes. He played four-plus hours — believed to be his longest performance — beginning with a cover of Joe South’s 1970 song “Walk a Mile in My Shoes” and ending with his own “All Along the Watchtower.”

“That was a good one,” Phelps recalled.

Phelps — who bought out Spoerndle's stake in Toad's in 1998 — believes the secret to the venue's longevity has been bringing in acts from different genres, along with events such as dance nights and “battle of the bands”. Rap shows especially draw big crowds, he said.

Naughty by Nature and Public Enemy played Toad’s in 1992. After releasing his first album, Kanye West played there in 2004 with John Legend on keyboards. Drake played Toad’s in 2009, early in his music career. And Snoop Dogg stopped by to perform in 2012 and 2014.

“When you have all these things, all ages, all different styles of music, and you have some dance parties to fill in where you need them, especially during a slow year, it brings enough capital in so that you can stay in business and keep moving forward,” Phelps said.

On a recent night, as local groups took the stage for a battle of the bands contest, many were in awe of playing in the same space where so many legends have performed.

Rook Bazinet, the 22-year-old singer of the Hartford-based emo group Nor Fork, said the band members' parents told them of all the big acts they'd seen at the New Haven hot spot over the years. Bazinet's mom had seen Phish there in the '90s.

“Me, the Stones and Bob Dylan,” Bazinet added. “I’m glad to be on that list.”

Harmonica player Don DeStefano, right, plays with the band Creamery Station at Toad's Place in New Haven, Conn., on Friday, May 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Jessica Hill)

A poster of Jon Bon Jovi with the date he performed is displayed in the women's bathroom at Toad's Place in New Haven, Conn., on Friday, May 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Jessica Hill)

Brian Phelps, owner of Toad's Place, looks over newspaper clippings he has collected about the famous concert venue in New Haven, Conn., on Friday, May 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Jessica Hill)

FILE - The Rolling Stones perform during an impromptu concert at the Toad's Place nightclub in New Haven, Conn., early Sunday, Aug. 13, 1989. (AP Photo/Dimo Safari, File)

A mural of past concerts at Toad's Place is displayed above one of the bars in New Haven, Conn., on Friday, May 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Jessica Hill)

ATLANTA (AP) — Donald Trump would not be the first president to invoke the Insurrection Act, as he has threatened, so that he can send U.S. military forces to Minnesota.

But he'd be the only commander in chief to use the 19th-century law to send troops to quell protests that started because of federal officers the president already has sent to the area — one of whom shot and killed a U.S. citizen.

The law, which allows presidents to use the military domestically, has been invoked on more than two dozen occasions — but rarely since the 20th Century's Civil Rights Movement.

Federal forces typically are called to quell widespread violence that has broken out on the local level — before Washington's involvement and when local authorities ask for help. When presidents acted without local requests, it was usually to enforce the rights of individuals who were being threatened or not protected by state and local governments. A third scenario is an outright insurrection — like the Confederacy during the Civil War.

Experts in constitutional and military law say none of that clearly applies in Minneapolis.

“This would be a flagrant abuse of the Insurrection Act in a way that we've never seen,” said Joseph Nunn, an attorney at the Brennan Center for Justice's Liberty and National Security Program. “None of the criteria have been met.”

William Banks, a Syracuse University professor emeritus who has written extensively on the domestic use of the military, said the situation is “a historical outlier” because the violence Trump wants to end “is being created by the federal civilian officers” he sent there.

But he also cautioned Minnesota officials would have “a tough argument to win” in court, because the judiciary is hesitant to challenge “because the courts are typically going to defer to the president” on his military decisions.

Here is a look at the law, how it's been used and comparisons to Minneapolis.

George Washington signed the first version in 1792, authorizing him to mobilize state militias — National Guard forerunners — when “laws of the United States shall be opposed, or the execution thereof obstructed.”

He and John Adams used it to quash citizen uprisings against taxes, including liquor levies and property taxes that were deemed essential to the young republic's survival.

Congress expanded the law in 1807, restating presidential authority to counter “insurrection or obstruction” of laws. Nunn said the early statutes recognized a fundamental “Anglo-American tradition against military intervention in civilian affairs” except “as a tool of last resort.”

The president argues Minnesota officials and citizens are impeding U.S. law by protesting his agenda and the presence of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers and Customs and Border Protection officers. Yet early statutes also defined circumstances for the law as unrest “too powerful to be suppressed by the ordinary course” of law enforcement.

There are between 2,000 and 3,000 federal authorities in the Minneapolis-St. Paul metro area, compared to Minneapolis, which has fewer than 600 police officers. Protesters' and bystanders' video, meanwhile, has shown violence initiated by federal officers, with the interactions growing more frequent since Renee Good was shot three times and killed.

“ICE has the legal authority to enforce federal immigration laws,” Nunn said. “But what they're doing is a sort of lawless, violent behavior” that goes beyond their legal function and “foments the situation” Trump wants to suppress.

“They can't intentionally create a crisis, then turn around to do a crackdown,” he said, adding that the Constitutional requirement for a president to “faithfully execute the laws” means Trump must wield his power, on immigration and the Insurrection Act, “in good faith.”

Courts have blocked some of Trump's efforts to deploy the National Guard, but he'd argue with the Insurrection Act that he does not need a state's permission to send troops.

That traces to President Abraham Lincoln, who held in 1861 that Southern states could not legitimately secede. So, he convinced Congress to give him express power to deploy U.S. troops, without asking, into Confederate states he contended were still in the Union. Quite literally, Lincoln used the act as a legal basis to fight the Civil War.

Nunn said situations beyond such a clear insurrection as the Confederacy still require a local request or another trigger that Congress added after the Civil War: protecting individual rights. Ulysses S. Grant used that provision to send troops to counter the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacists who ignored the 14th and 15th amendments and civil rights statutes.

During post-war industrialization, violence erupted around strikes and expanding immigration — and governors sought help.

President Rutherford B. Hayes granted state requests during the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 after striking workers, state forces and local police clashed, leading to dozens of deaths. Grover Cleveland granted a Washington state governor's request — at that time it was a U.S. territory — to help protect Chinese citizens who were being attacked by white rioters. President Woodrow Wilson sent troops to Colorado in 1914 amid a coal strike after workers were killed.

Federal troops helped diffuse each situation.

Banks stressed that the law then and now presumes that federal resources are needed only when state and local authorities are overwhelmed — and Minnesota leaders say their cities would be stable and safe if Trump's feds left.

As Grant had done, mid-20th century presidents used the act to counter white supremacists.

Franklin Roosevelt dispatched 6,000 troops to Detroit — more than double the U.S. forces in Minneapolis — after race riots that started with whites attacking Black residents. State officials asked for FDR's aid after riots escalated, in part, Nunn said, because white local law enforcement joined in violence against Black residents. Federal troops calmed the city after dozens of deaths, including 17 Black residents killed by local police.

Once the Civil Rights Movement began, presidents sent authorities to Southern states without requests or permission, because local authorities defied U.S. civil rights law and fomented violence themselves.

Dwight Eisenhower enforced integration at Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas; John F. Kennedy sent troops to the University of Mississippi after riots over James Meredith's admission and then pre-emptively to ensure no violence upon George Wallace's “Stand in the Schoolhouse Door” to protest the University of Alabama's integration.

“There could have been significant loss of life from the rioters” in Mississippi, Nunn said.

Lyndon Johnson protected the 1965 Voting Rights March from Selma to Montgomery after Wallace's troopers attacked marchers' on their first peaceful attempt.

Johnson also sent troops to multiple U.S. cities in 1967 and 1968 after clashes between residents and police escalated. The same thing happened in Los Angeles in 1992, the last time the Insurrection Act was invoked.

Riots erupted after a jury failed to convict four white police officers of excessive use of force despite video showing them beating a Rodney King, a Black man. California Gov. Pete Wilson asked President George H.W. Bush for support.

Bush authorized about 4,000 troops — but after he had publicly expressed displeasure over the trial verdict. He promised to “restore order” yet directed the Justice Department to open a civil rights investigation, and two of the L.A. officers were later convicted in federal court.

President Donald Trump answers questions after signing a bill that returns whole milk to school cafeterias across the country, in the Oval Office of the White House, Wednesday, Jan. 14, 2026, in Washington. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon)