Two homes on the North Carolina Outer Banks sit precariously in the high waves with their days seemingly numbered. Since 2020, 11 neighboring homes have fallen into the Atlantic Ocean.

While the swells from storms like Hurricane Erin make things worse, the conditions threatening the houses are always present — beach erosion and climate change are sending the ocean closer and closer to their front doors.

The two houses in the surf in Rodanthe have received plenty of attention as Erin passes several hundred miles (kilometers) to the east. The village of about 200 people sticks out further into the Atlantic than any other part of North Carolina.

Jan Richards looked at the houses Tuesday as high tides sent surges of water into the support beams on the two-story homes. She gestured where two other houses used to be before their recent collapse.

“The one in the middle fell last year. It fell into that house. So you can see where it crashed into that house. But that has been really resilient and has stayed put up until probably this storm,” Richards said.

At least 11 other houses have toppled into the surf in Rodanthe in the past five years, according to the National Park Service, which oversees much of the Outer Banks.

Barrier islands like the Outer Banks were never an ideal place for development, according to experts. The islands typically form as waves deposit sediment off the mainland. And they move based on weather patterns and other ocean forces. Some even disappear.

Decades ago, houses and other buildings were smaller, less elaborate and easier to move from the encroaching surf, said David Hallac, superintendent of the Cape Hatteras National Seashore.

“Perhaps it was more well understood in the past that the barrier island was dynamic, that it was moving,” Hallac said. “And if you built something on the beachfront it may not be there forever or it may need to be moved.”

Even the largest structures aren't immune. Twenty-six years ago the Outer Banks most famous landmark, the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse had to be moved over a half-mile (880 meters) inland.

When it was built in 1870, the lighthouse was 1,500 feet (457 meters) from the ocean. Fifty years later, the Atlantic was 300 feet (91 meters) away. And erosion keeps coming. Some places along the Outer Banks lose as much as 10 to 15 feet (3 to 4.5 meters) of beachfront a year, Hallac said.

“And so every year, 10 to 15 feet of that white sandy beach is gone,” Hallac said. “And then the dunes and then the back-dune area. And then all of a sudden, the foreshore, that area between low water and high water, is right up next to somebody’s backyard. And then the erosion continues.”

The ocean attacks the houses by the wooden pilings that provide their foundation and keep them above the water. The supports could be 15 feet (4.5 meters) deep. But the surf slowly takes away the sand that is packed around them.

“It’s like a toothpick in wet sand or even a beach umbrella,” Hallac said. “The deeper you put it, the more likely it is to stand up straight and resist leaning over. But if you only put it down a few inches, it doesn’t take much wind for that umbrella to start leaning. And it starts to tip over.”

A single home collapse can shed debris up to 15 miles (25 kilometers) along the coast, according to a report from a group of federal, state and local officials who are studying threatened oceanfront structures in North Carolina. Collapses can injure beachgoers and lead to potential contamination from septic tanks, among other environmental concerns.

The report noted that 750 of nearly 8,800 oceanfront structures in North Carolina are considered at risk from erosion.

Among the possible solutions is hauling dredged sand to eroding beaches, something that is already being done in other communities on the Outer Banks and East Coast. But it could cost $40 million or more in Rodanthe, posing a major financial challenge for its small tax base.

Other ideas include buying out threatened properties, moving or demolishing them. But those options are also very expensive. And funding is limited.

Braxton Davis, executive director of the North Carolina Coastal Federation, a nonprofit, said the problem isn’t limited to Rodanthe or even to North Carolina. He pointed to erosion issues along California’s coast, the Great Lakes and some of the nation’s rivers.

“This is a national issue,” Davis said, adding that sea levels are rising and “the situation is only going to become worse.”

FILE - The Cape Hatteras lighthouse stands, Aug. 29, 1995 on the Outer Banks of North Carolina. (AP Photo/Ruth Fremson, File)

Maggie Ford takes a photo of a teetering stilt house being pummeled by waves from Hurricane Erin in Rodanthe, N.C., on Wednesday, Aug. 20, 2025. (AP Photo/Allen G. Breed)

Two houses sit out in the heavy surf as Hurricane Erin passes offshore at Rodanthe, N.C., on Tuesday, Aug. 19, 2025. (AP Photo/Allen G. Breed)

ATLANTA (AP) — Donald Trump would not be the first president to invoke the Insurrection Act, as he has threatened, so that he can send U.S. military forces to Minnesota.

But he'd be the only commander in chief to use the 19th-century law to send troops to quell protests that started because of federal officers the president already has sent to the area — one of whom shot and killed a U.S. citizen.

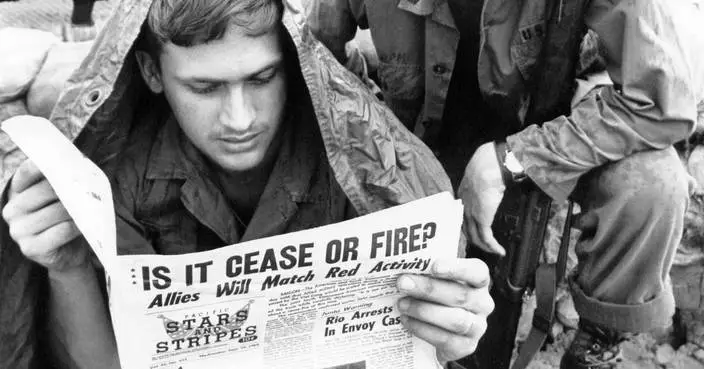

The law, which allows presidents to use the military domestically, has been invoked on more than two dozen occasions — but rarely since the 20th Century's Civil Rights Movement.

Federal forces typically are called to quell widespread violence that has broken out on the local level — before Washington's involvement and when local authorities ask for help. When presidents acted without local requests, it was usually to enforce the rights of individuals who were being threatened or not protected by state and local governments. A third scenario is an outright insurrection — like the Confederacy during the Civil War.

Experts in constitutional and military law say none of that clearly applies in Minneapolis.

“This would be a flagrant abuse of the Insurrection Act in a way that we've never seen,” said Joseph Nunn, an attorney at the Brennan Center for Justice's Liberty and National Security Program. “None of the criteria have been met.”

William Banks, a Syracuse University professor emeritus who has written extensively on the domestic use of the military, said the situation is “a historical outlier” because the violence Trump wants to end “is being created by the federal civilian officers” he sent there.

But he also cautioned Minnesota officials would have “a tough argument to win” in court, because the judiciary is hesitant to challenge “because the courts are typically going to defer to the president” on his military decisions.

Here is a look at the law, how it's been used and comparisons to Minneapolis.

George Washington signed the first version in 1792, authorizing him to mobilize state militias — National Guard forerunners — when “laws of the United States shall be opposed, or the execution thereof obstructed.”

He and John Adams used it to quash citizen uprisings against taxes, including liquor levies and property taxes that were deemed essential to the young republic's survival.

Congress expanded the law in 1807, restating presidential authority to counter “insurrection or obstruction” of laws. Nunn said the early statutes recognized a fundamental “Anglo-American tradition against military intervention in civilian affairs” except “as a tool of last resort.”

The president argues Minnesota officials and citizens are impeding U.S. law by protesting his agenda and the presence of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers and Customs and Border Protection officers. Yet early statutes also defined circumstances for the law as unrest “too powerful to be suppressed by the ordinary course” of law enforcement.

There are between 2,000 and 3,000 federal authorities in the Minneapolis-St. Paul metro area, compared to Minneapolis, which has fewer than 600 police officers. Protesters' and bystanders' video, meanwhile, has shown violence initiated by federal officers, with the interactions growing more frequent since Renee Good was shot three times and killed.

“ICE has the legal authority to enforce federal immigration laws,” Nunn said. “But what they're doing is a sort of lawless, violent behavior” that goes beyond their legal function and “foments the situation” Trump wants to suppress.

“They can't intentionally create a crisis, then turn around to do a crackdown,” he said, adding that the Constitutional requirement for a president to “faithfully execute the laws” means Trump must wield his power, on immigration and the Insurrection Act, “in good faith.”

Courts have blocked some of Trump's efforts to deploy the National Guard, but he'd argue with the Insurrection Act that he does not need a state's permission to send troops.

That traces to President Abraham Lincoln, who held in 1861 that Southern states could not legitimately secede. So, he convinced Congress to give him express power to deploy U.S. troops, without asking, into Confederate states he contended were still in the Union. Quite literally, Lincoln used the act as a legal basis to fight the Civil War.

Nunn said situations beyond such a clear insurrection as the Confederacy still require a local request or another trigger that Congress added after the Civil War: protecting individual rights. Ulysses S. Grant used that provision to send troops to counter the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacists who ignored the 14th and 15th amendments and civil rights statutes.

During post-war industrialization, violence erupted around strikes and expanding immigration — and governors sought help.

President Rutherford B. Hayes granted state requests during the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 after striking workers, state forces and local police clashed, leading to dozens of deaths. Grover Cleveland granted a Washington state governor's request — at that time it was a U.S. territory — to help protect Chinese citizens who were being attacked by white rioters. President Woodrow Wilson sent troops to Colorado in 1914 amid a coal strike after workers were killed.

Federal troops helped diffuse each situation.

Banks stressed that the law then and now presumes that federal resources are needed only when state and local authorities are overwhelmed — and Minnesota leaders say their cities would be stable and safe if Trump's feds left.

As Grant had done, mid-20th century presidents used the act to counter white supremacists.

Franklin Roosevelt dispatched 6,000 troops to Detroit — more than double the U.S. forces in Minneapolis — after race riots that started with whites attacking Black residents. State officials asked for FDR's aid after riots escalated, in part, Nunn said, because white local law enforcement joined in violence against Black residents. Federal troops calmed the city after dozens of deaths, including 17 Black residents killed by local police.

Once the Civil Rights Movement began, presidents sent authorities to Southern states without requests or permission, because local authorities defied U.S. civil rights law and fomented violence themselves.

Dwight Eisenhower enforced integration at Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas; John F. Kennedy sent troops to the University of Mississippi after riots over James Meredith's admission and then pre-emptively to ensure no violence upon George Wallace's “Stand in the Schoolhouse Door” to protest the University of Alabama's integration.

“There could have been significant loss of life from the rioters” in Mississippi, Nunn said.

Lyndon Johnson protected the 1965 Voting Rights March from Selma to Montgomery after Wallace's troopers attacked marchers' on their first peaceful attempt.

Johnson also sent troops to multiple U.S. cities in 1967 and 1968 after clashes between residents and police escalated. The same thing happened in Los Angeles in 1992, the last time the Insurrection Act was invoked.

Riots erupted after a jury failed to convict four white police officers of excessive use of force despite video showing them beating a Rodney King, a Black man. California Gov. Pete Wilson asked President George H.W. Bush for support.

Bush authorized about 4,000 troops — but after he had publicly expressed displeasure over the trial verdict. He promised to “restore order” yet directed the Justice Department to open a civil rights investigation, and two of the L.A. officers were later convicted in federal court.

President Donald Trump answers questions after signing a bill that returns whole milk to school cafeterias across the country, in the Oval Office of the White House, Wednesday, Jan. 14, 2026, in Washington. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon)