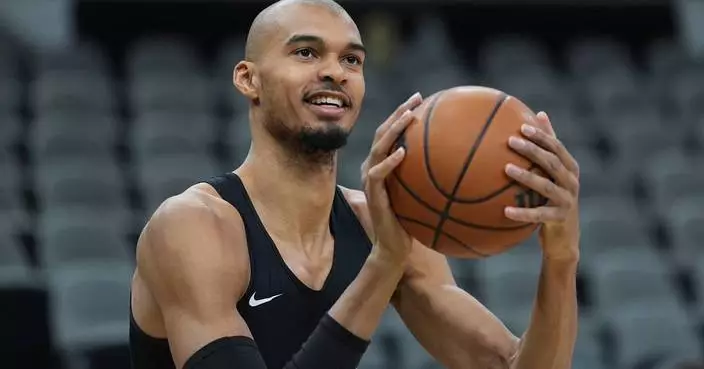

Josh Sargent could end a 2,118-day international goal drought Saturday when the United States plays South Korea in the first of eight friendlies coach Mauricio Pochettino will use to evaluate his player pool before his pre-World Cup training camp.

Rather than dwell on the dry spell, Sargent would rather concentrate on his hot start for Norwich in England's second-tier League Championship. The 25-year-old from O'Fallon, Missouri, has scored six goals in his club's first five games and captained the team in four matches.

“Of course I know it’s been a while,” he said Tuesday before the Americans' first training session with the full roster. “I’m doing so well at the club level at the moment — I just keep reminding myself how well I’m doing there. I know I can score goals and I know it’s a matter of time that I’m going to score for the national team. So just going to put my head down and keep working hard and I know the goals will come.”

Sargent joined Werder Bremen at the start of 2018, just before turning 18, and debuted that December. Instantly recognizable because of his bushy red hair, Sargent scored 11 Bundesliga goals in 70 games over three seasons before the team was demoted to the second division for 2021-22, then transferred to Norwich and scored four goals in 2022-23, getting braces against Bournemouth in the League Cup and Watford in the Premier League.

He remained with the Canaries after they were relegated and made three World Cup appearances for the U.S. that included starts against Wales and Iran. Sargent struggled with ankle injuries that cut short his 2021-22 season and led to surgery that caused a four-month layoff in the fall of 2023. Last season, he was out 2 1/2 months because of groin surgery and scored 11 goals in his final 20 league matches.

“Been feeling good for a while now,” Sargent said. “I think Norwich has done a good job of taking care of me and getting me back to a good spot. Obviously continue to do certain exercises in the gym to keep myself healthy.”

His strong start this season led to inquiries for a possible transfer to a first-tier club. Asked whether Sunderland and Wolfsburg had tried to acquired him, Sargent responded: “There were interests from multiple clubs. Obviously in the end didn’t work out, but that’s football sometimes.”

Just seven of 21 American goals in 12 matches this year have come from strikers: five by Patrick Agyemang ( recovering from hernia surgery) and one each by Haji Wright and Brian White. Sargent and Folarin Balogun, attending his first camp under Pochettino, are competing with them for World Cup roster spots along with Ricardo Pepi and Damion Downs.

Sargent was bypassed for this summer's CONCACAF Gold Cup, getting his notification by email. Pochettino didn't answer directly when asked about his Sargent's current selection, saying every player in the pool has “the possibility and the chance to show their quality and to convince us that they deserve to be in a place on the national team.”

Sargent scored in his U.S. debut against Bolivia on May 28, 2018, and has five goals in 28 international appearances — none since a pair vs. Cuba in the CONCACAF Nations League on Nov. 19, 2019.

“I’ve known that the guy can score goals since he was 15, 16 years old,” said defender Tim Ream, a St. Louis native who at 37 is the senior current America player. “It's not something that we're worried about. You look at what he’s doing at Norwich and at club, and the types of goals that he’s scoring, they’re all different. ... It's a matter of putting his head down and continuing to work and doing the things that he’s good at and the goals will definitely come.”

Americans over the years have put themselves in poor positions ahead of World Cups by spending time with clubs that have limited their playing time. Sargent is happy with his current team.

“A lot of decisions had to be made, not just for myself, but for my family,” said Sargent, who has a 3-year-old daughter, “Overall, I think I’m in a good spot at Norwich. I’m at a place where I know I can score goals, which, of course, is important going into the World Cup.”

AP soccer: https://apnews.com/hub/soccer

Norwich City's Josh Sargent scores his sides first goal from the penalty spot during a Sky Bet Championship soccer match against Blackburn Rovers, Saturday, Aug. 30, 2025, at Ewood Park in Blackburn, England (Cody Froggatt/PA via AP)

Norwich City's Josh Sargent, left, celebrates with Ben Chrisene after scoring his sides second goal during a Sky Bet Championship soccer match against Blackburn Rovers, Saturday, Aug. 30, 2025, at Ewood Park in Blackburn, England (Cody Froggatt/PA via AP)

ATLANTA (AP) — Donald Trump would not be the first president to invoke the Insurrection Act, as he has threatened, so that he can send U.S. military forces to Minnesota.

But he'd be the only commander in chief to use the 19th-century law to send troops to quell protests that started because of federal officers the president already has sent to the area — one of whom shot and killed a U.S. citizen.

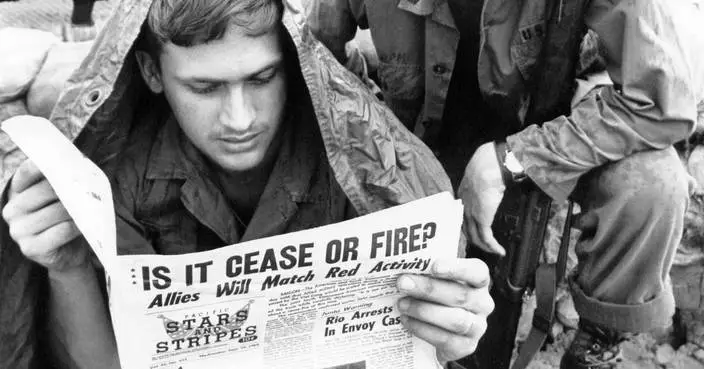

The law, which allows presidents to use the military domestically, has been invoked on more than two dozen occasions — but rarely since the 20th Century's Civil Rights Movement.

Federal forces typically are called to quell widespread violence that has broken out on the local level — before Washington's involvement and when local authorities ask for help. When presidents acted without local requests, it was usually to enforce the rights of individuals who were being threatened or not protected by state and local governments. A third scenario is an outright insurrection — like the Confederacy during the Civil War.

Experts in constitutional and military law say none of that clearly applies in Minneapolis.

“This would be a flagrant abuse of the Insurrection Act in a way that we've never seen,” said Joseph Nunn, an attorney at the Brennan Center for Justice's Liberty and National Security Program. “None of the criteria have been met.”

William Banks, a Syracuse University professor emeritus who has written extensively on the domestic use of the military, said the situation is “a historical outlier” because the violence Trump wants to end “is being created by the federal civilian officers” he sent there.

But he also cautioned Minnesota officials would have “a tough argument to win” in court, because the judiciary is hesitant to challenge “because the courts are typically going to defer to the president” on his military decisions.

Here is a look at the law, how it's been used and comparisons to Minneapolis.

George Washington signed the first version in 1792, authorizing him to mobilize state militias — National Guard forerunners — when “laws of the United States shall be opposed, or the execution thereof obstructed.”

He and John Adams used it to quash citizen uprisings against taxes, including liquor levies and property taxes that were deemed essential to the young republic's survival.

Congress expanded the law in 1807, restating presidential authority to counter “insurrection or obstruction” of laws. Nunn said the early statutes recognized a fundamental “Anglo-American tradition against military intervention in civilian affairs” except “as a tool of last resort.”

The president argues Minnesota officials and citizens are impeding U.S. law by protesting his agenda and the presence of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers and Customs and Border Protection officers. Yet early statutes also defined circumstances for the law as unrest “too powerful to be suppressed by the ordinary course” of law enforcement.

There are between 2,000 and 3,000 federal authorities in the Minneapolis-St. Paul metro area, compared to Minneapolis, which has fewer than 600 police officers. Protesters' and bystanders' video, meanwhile, has shown violence initiated by federal officers, with the interactions growing more frequent since Renee Good was shot three times and killed.

“ICE has the legal authority to enforce federal immigration laws,” Nunn said. “But what they're doing is a sort of lawless, violent behavior” that goes beyond their legal function and “foments the situation” Trump wants to suppress.

“They can't intentionally create a crisis, then turn around to do a crackdown,” he said, adding that the Constitutional requirement for a president to “faithfully execute the laws” means Trump must wield his power, on immigration and the Insurrection Act, “in good faith.”

Courts have blocked some of Trump's efforts to deploy the National Guard, but he'd argue with the Insurrection Act that he does not need a state's permission to send troops.

That traces to President Abraham Lincoln, who held in 1861 that Southern states could not legitimately secede. So, he convinced Congress to give him express power to deploy U.S. troops, without asking, into Confederate states he contended were still in the Union. Quite literally, Lincoln used the act as a legal basis to fight the Civil War.

Nunn said situations beyond such a clear insurrection as the Confederacy still require a local request or another trigger that Congress added after the Civil War: protecting individual rights. Ulysses S. Grant used that provision to send troops to counter the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacists who ignored the 14th and 15th amendments and civil rights statutes.

During post-war industrialization, violence erupted around strikes and expanding immigration — and governors sought help.

President Rutherford B. Hayes granted state requests during the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 after striking workers, state forces and local police clashed, leading to dozens of deaths. Grover Cleveland granted a Washington state governor's request — at that time it was a U.S. territory — to help protect Chinese citizens who were being attacked by white rioters. President Woodrow Wilson sent troops to Colorado in 1914 amid a coal strike after workers were killed.

Federal troops helped diffuse each situation.

Banks stressed that the law then and now presumes that federal resources are needed only when state and local authorities are overwhelmed — and Minnesota leaders say their cities would be stable and safe if Trump's feds left.

As Grant had done, mid-20th century presidents used the act to counter white supremacists.

Franklin Roosevelt dispatched 6,000 troops to Detroit — more than double the U.S. forces in Minneapolis — after race riots that started with whites attacking Black residents. State officials asked for FDR's aid after riots escalated, in part, Nunn said, because white local law enforcement joined in violence against Black residents. Federal troops calmed the city after dozens of deaths, including 17 Black residents killed by local police.

Once the Civil Rights Movement began, presidents sent authorities to Southern states without requests or permission, because local authorities defied U.S. civil rights law and fomented violence themselves.

Dwight Eisenhower enforced integration at Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas; John F. Kennedy sent troops to the University of Mississippi after riots over James Meredith's admission and then pre-emptively to ensure no violence upon George Wallace's “Stand in the Schoolhouse Door” to protest the University of Alabama's integration.

“There could have been significant loss of life from the rioters” in Mississippi, Nunn said.

Lyndon Johnson protected the 1965 Voting Rights March from Selma to Montgomery after Wallace's troopers attacked marchers' on their first peaceful attempt.

Johnson also sent troops to multiple U.S. cities in 1967 and 1968 after clashes between residents and police escalated. The same thing happened in Los Angeles in 1992, the last time the Insurrection Act was invoked.

Riots erupted after a jury failed to convict four white police officers of excessive use of force despite video showing them beating a Rodney King, a Black man. California Gov. Pete Wilson asked President George H.W. Bush for support.

Bush authorized about 4,000 troops — but after he had publicly expressed displeasure over the trial verdict. He promised to “restore order” yet directed the Justice Department to open a civil rights investigation, and two of the L.A. officers were later convicted in federal court.

President Donald Trump answers questions after signing a bill that returns whole milk to school cafeterias across the country, in the Oval Office of the White House, Wednesday, Jan. 14, 2026, in Washington. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon)