LIVERPOOL, England (AP) — Keir Starmer never had much of a political honeymoon. Now some members of his political party are considering divorce.

Little more than a year after winning power in a landslide, Britain’s prime minister is fighting to keep the support of his party, and to fend off Nigel Farage, whose hard-right Reform UK has a consistent lead in opinion polls.

Click to Gallery

Britain's Prime Minister Keir Starmer and Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, right, attend the Labour Party Conference in Liverpool, England, Sunday Sept. 28, 2025. (Stefan Rousseau/PA via AP)

Britain's Prime Minister Keir Starmer speaks during the Labour Party Conference in Liverpool, England, Sunday Sept. 28, 2025. (Danny Lawson/PA via AP)

Britain's Prime Minister Keir Starmer attends the Labour Party Conference in Liverpool, England, Sunday Sept. 28, 2025. (Danny Lawson/PA via AP)

British Prime Minister Keir Starmer speaks on the BBC 1 current affairs programme, Sunday, Sept. 28, 2025, with Laura Kuenssberg in Liverpool. (Stefan Rousseau/Pool via AP)

British Prime Minister Keir Starmer speaks on the BBC 1 current affairs programme, Sunday, Sept. 28, 2025, with Laura Kuenssberg in Liverpool. (Stefan Rousseau/Pool via AP)

Britain's Prime Minister Keir Starmer and his wife Victoria arrive ahead of the Labour Party Conference at the ACC Liverpool, in Liverpool, England, Saturday, Sept. 27, 2025. (Stefan Rousseau/PA via AP)

Britain's Prime Minister Keir Starmer listens during a pannel discussion at the Progress Global Action Summit, in London, Friday, Sept. 26, 2025. (AP Photo/Kin Cheung)

The next election is as much as four years away, but as thousands of Labour Party members gathered Sunday for their annual conference beside the River Mersey in Liverpool, many lawmakers were anxious — and a potential leadership rival to Starmer has emerged in Andy Burnham, the ambitious mayor of Manchester.

Starmer shrugged off the discontent, telling the BBC that “in politics, there are always going to be comments about leaders and leadership” and insisting the government had “achieved great things in the first year.”

“I just need the space to get on and do what we need to do,” he said.

But Tim Bale, professor of politics at Queen Mary University of London, said the party's mood is “febrile.”

“They’ve only been in government a year and they’ve got a big majority, but most voters seem to be quite disappointed and disillusioned with the government," he said. “And they also have a very low opinion of Keir Starmer.”

Since ending 14 years of Conservative rule with his July 2024 election victory, Starmer has struggled to deliver the economic growth he promised. Inflation remains stubbornly high and the economic outlook subdued, frustrating efforts to repair tattered public services and ease the cost of living.

A global backdrop of Russia’s war in Ukraine and U.S. President Donald Trump’s tariffs hasn’t helped. Even though Britain managed to secure a trade deal easing import duties on some U.K. goods, the autumn budget statement in November looks set to be a grim choice between tax increases and spending cuts — maybe both.

In his big conference speech on Tuesday, Starmer will try to set out a sweeping vision to energize Labour’s grassroots, something critics say has been lacking under his managerial command. He’ll also seek to persuade party members, and voters, that he has learned from his mistakes and stabilized a sometimes wobbly government.

In the last few weeks Starmer has lost his deputy prime minister, Angela Rayner, who quit over a tax error on a home purchase, and fired Britain’s ambassador to Washington, Peter Mandelson, after revelations about his past friendship with convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein. There have also been several exits from Starmer's backroom team, adding to a sense of disarray.

Now Burnham, who served in past Labour governments, is emerging as a nascent rival. The Manchester mayor says lawmakers have approached him about a leadership bid, even though he is not currently a member of Parliament.

Burnham said Sunday that he wanted to “launch a debate at this conference about direction (of the party) and getting a plan to defeat Reform.

“I do think we need a story for this government that connects more with people," he said, adding those calling for “simplistic statements of loyalty" to Starmer are "underestimating the peril the party is in.”

Starmer’s dilemma is that he faces opposition on multiple issues from both right and left. Outside the conference venue in Liverpool, some 200 miles (32 kilometers) northwest of London, scores of people protested a government plan for digital ID cards, while a separate demonstration opposed the government’s decision to ban the activist group Palestine Action as a terrorist organization.

The threat posed by Reform was a top issue among Labour delegates in Liverpool. Farage's anti-establishment, anti-immigrant message, with its echoes of President Donald Trump's MAGA movement, has homed in on the issue of thousands of migrants in small boats arriving in Britain across the English Channel.

More than 30,000 people have made the dangerous crossing from France so far this year despite efforts by authorities in Britain, France and other countries to crack down on people-smuggling gangs.

Far-right activists have been involved in protests outside hotels housing asylum-seekers across the U.K., and a march organized by anti-immigration campaigner Tommy Robinson attracted more than 100,000 people in London this month.

Starmer has acknowledged voters’ concerns about migration but condemned Robinson’s anti-immigrant rhetoric and accused Farage of sowing division with plans to deport immigrants who are in the U.K. legally that Starmer called “racist” and “immoral.”

Farage’s party has only five lawmakers in the 650 seat House of Commons, and Labour has more than 400. Nonetheless Starmer said Reform, and not the main opposition Conservatives, is now Labour’s chief opponent.

In a speech on Friday, he said the defining political battle of our times is between a “politics of predatory grievance” that seeks to foster division and “patriotic renewal … underpinned by the values of dignity and respect, equality and fairness.”

“There’s a battle for the soul of this country now as to what sort of country we want to be,” he said.

The government does not have to call an election until 2029, but pressure will mount on Starmer if, as many predict, Labour does badly in local and regional elections in May.

Bale said that, for now, the best policy for the government is to “keep calm and carry on.”

“Over time, greater investment in public services, in particular the health service, will probably begin to show some fruit,” he said. “The economy may turn around as the government’s policies have some effect. They may get the small boats problem under control over time.

“But it really is a case of just kind of waiting it out — and perhaps hoping that Nigel Farage and Reform’s bubble will burst.”

Britain's Prime Minister Keir Starmer and Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, right, attend the Labour Party Conference in Liverpool, England, Sunday Sept. 28, 2025. (Stefan Rousseau/PA via AP)

Britain's Prime Minister Keir Starmer speaks during the Labour Party Conference in Liverpool, England, Sunday Sept. 28, 2025. (Danny Lawson/PA via AP)

Britain's Prime Minister Keir Starmer attends the Labour Party Conference in Liverpool, England, Sunday Sept. 28, 2025. (Danny Lawson/PA via AP)

British Prime Minister Keir Starmer speaks on the BBC 1 current affairs programme, Sunday, Sept. 28, 2025, with Laura Kuenssberg in Liverpool. (Stefan Rousseau/Pool via AP)

British Prime Minister Keir Starmer speaks on the BBC 1 current affairs programme, Sunday, Sept. 28, 2025, with Laura Kuenssberg in Liverpool. (Stefan Rousseau/Pool via AP)

Britain's Prime Minister Keir Starmer and his wife Victoria arrive ahead of the Labour Party Conference at the ACC Liverpool, in Liverpool, England, Saturday, Sept. 27, 2025. (Stefan Rousseau/PA via AP)

Britain's Prime Minister Keir Starmer listens during a pannel discussion at the Progress Global Action Summit, in London, Friday, Sept. 26, 2025. (AP Photo/Kin Cheung)

ATLANTA (AP) — Donald Trump would not be the first president to invoke the Insurrection Act, as he has threatened, so that he can send U.S. military forces to Minnesota.

But he'd be the only commander in chief to use the 19th-century law to send troops to quell protests that started because of federal officers the president already has sent to the area — one of whom shot and killed a U.S. citizen.

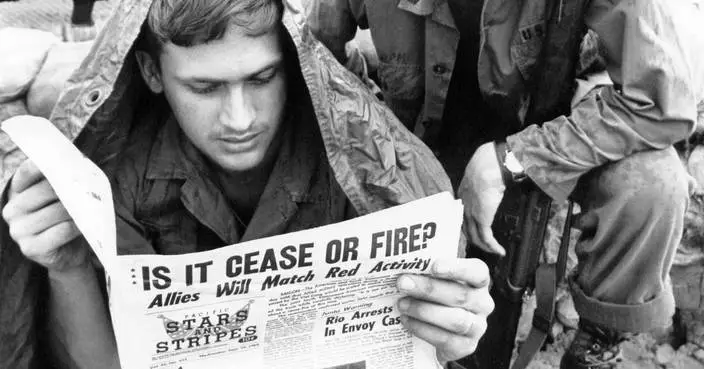

The law, which allows presidents to use the military domestically, has been invoked on more than two dozen occasions — but rarely since the 20th Century's Civil Rights Movement.

Federal forces typically are called to quell widespread violence that has broken out on the local level — before Washington's involvement and when local authorities ask for help. When presidents acted without local requests, it was usually to enforce the rights of individuals who were being threatened or not protected by state and local governments. A third scenario is an outright insurrection — like the Confederacy during the Civil War.

Experts in constitutional and military law say none of that clearly applies in Minneapolis.

“This would be a flagrant abuse of the Insurrection Act in a way that we've never seen,” said Joseph Nunn, an attorney at the Brennan Center for Justice's Liberty and National Security Program. “None of the criteria have been met.”

William Banks, a Syracuse University professor emeritus who has written extensively on the domestic use of the military, said the situation is “a historical outlier” because the violence Trump wants to end “is being created by the federal civilian officers” he sent there.

But he also cautioned Minnesota officials would have “a tough argument to win” in court, because the judiciary is hesitant to challenge “because the courts are typically going to defer to the president” on his military decisions.

Here is a look at the law, how it's been used and comparisons to Minneapolis.

George Washington signed the first version in 1792, authorizing him to mobilize state militias — National Guard forerunners — when “laws of the United States shall be opposed, or the execution thereof obstructed.”

He and John Adams used it to quash citizen uprisings against taxes, including liquor levies and property taxes that were deemed essential to the young republic's survival.

Congress expanded the law in 1807, restating presidential authority to counter “insurrection or obstruction” of laws. Nunn said the early statutes recognized a fundamental “Anglo-American tradition against military intervention in civilian affairs” except “as a tool of last resort.”

The president argues Minnesota officials and citizens are impeding U.S. law by protesting his agenda and the presence of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers and Customs and Border Protection officers. Yet early statutes also defined circumstances for the law as unrest “too powerful to be suppressed by the ordinary course” of law enforcement.

There are between 2,000 and 3,000 federal authorities in the Minneapolis-St. Paul metro area, compared to Minneapolis, which has fewer than 600 police officers. Protesters' and bystanders' video, meanwhile, has shown violence initiated by federal officers, with the interactions growing more frequent since Renee Good was shot three times and killed.

“ICE has the legal authority to enforce federal immigration laws,” Nunn said. “But what they're doing is a sort of lawless, violent behavior” that goes beyond their legal function and “foments the situation” Trump wants to suppress.

“They can't intentionally create a crisis, then turn around to do a crackdown,” he said, adding that the Constitutional requirement for a president to “faithfully execute the laws” means Trump must wield his power, on immigration and the Insurrection Act, “in good faith.”

Courts have blocked some of Trump's efforts to deploy the National Guard, but he'd argue with the Insurrection Act that he does not need a state's permission to send troops.

That traces to President Abraham Lincoln, who held in 1861 that Southern states could not legitimately secede. So, he convinced Congress to give him express power to deploy U.S. troops, without asking, into Confederate states he contended were still in the Union. Quite literally, Lincoln used the act as a legal basis to fight the Civil War.

Nunn said situations beyond such a clear insurrection as the Confederacy still require a local request or another trigger that Congress added after the Civil War: protecting individual rights. Ulysses S. Grant used that provision to send troops to counter the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacists who ignored the 14th and 15th amendments and civil rights statutes.

During post-war industrialization, violence erupted around strikes and expanding immigration — and governors sought help.

President Rutherford B. Hayes granted state requests during the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 after striking workers, state forces and local police clashed, leading to dozens of deaths. Grover Cleveland granted a Washington state governor's request — at that time it was a U.S. territory — to help protect Chinese citizens who were being attacked by white rioters. President Woodrow Wilson sent troops to Colorado in 1914 amid a coal strike after workers were killed.

Federal troops helped diffuse each situation.

Banks stressed that the law then and now presumes that federal resources are needed only when state and local authorities are overwhelmed — and Minnesota leaders say their cities would be stable and safe if Trump's feds left.

As Grant had done, mid-20th century presidents used the act to counter white supremacists.

Franklin Roosevelt dispatched 6,000 troops to Detroit — more than double the U.S. forces in Minneapolis — after race riots that started with whites attacking Black residents. State officials asked for FDR's aid after riots escalated, in part, Nunn said, because white local law enforcement joined in violence against Black residents. Federal troops calmed the city after dozens of deaths, including 17 Black residents killed by local police.

Once the Civil Rights Movement began, presidents sent authorities to Southern states without requests or permission, because local authorities defied U.S. civil rights law and fomented violence themselves.

Dwight Eisenhower enforced integration at Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas; John F. Kennedy sent troops to the University of Mississippi after riots over James Meredith's admission and then pre-emptively to ensure no violence upon George Wallace's “Stand in the Schoolhouse Door” to protest the University of Alabama's integration.

“There could have been significant loss of life from the rioters” in Mississippi, Nunn said.

Lyndon Johnson protected the 1965 Voting Rights March from Selma to Montgomery after Wallace's troopers attacked marchers' on their first peaceful attempt.

Johnson also sent troops to multiple U.S. cities in 1967 and 1968 after clashes between residents and police escalated. The same thing happened in Los Angeles in 1992, the last time the Insurrection Act was invoked.

Riots erupted after a jury failed to convict four white police officers of excessive use of force despite video showing them beating a Rodney King, a Black man. California Gov. Pete Wilson asked President George H.W. Bush for support.

Bush authorized about 4,000 troops — but after he had publicly expressed displeasure over the trial verdict. He promised to “restore order” yet directed the Justice Department to open a civil rights investigation, and two of the L.A. officers were later convicted in federal court.

President Donald Trump answers questions after signing a bill that returns whole milk to school cafeterias across the country, in the Oval Office of the White House, Wednesday, Jan. 14, 2026, in Washington. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon)