EAST RUTHERFORD, N.J. (AP) — Jaxson Dart was getting checked for a concussion during the New York Giants' prime-time game against Philadelphia, and Brian Daboll was running out of patience.

The coach pulled back the flap of the blue medical tent on the sideline and yelled inside to ask when his rookie quarterback's evaluation would be done. Running back Cam Skattebo also barged in while Dart was getting examined, and the next morning, the NFL launched an investigation into how the protocol was followed.

Click to Gallery

NFL chief medical officer Allen Sills, left, and New York Giants assistant athletic trainer Justin Maher, right, stand inside a blue medical tent Thursday, Oct. 9, 2025, at MetLife Stadium in East Rutherford, N.J. (AP Photo/Stephen Whyno)

A blue medical tent is viewed Thursday, Oct. 9, 2025, at MetLife Stadium in East Rutherford, N.J. (AP Photo/Stephen Whyno)

FILE - Cincinnati Bengals quarterback Joe Burrow, center, is exits the medical tent for the locker room after suffering an injury during the second quarter of an NFL football game against the Jacksonville Jaguars, Sept. 14, 2025, in Cincinnati. (AP Photo/Kareem Elgazzar, File)

FILE - New Orleans Saints wide receiver Chris Olave (12) enters the medical tent before being examined after a hard hit in the second half of an NFL football game against the Arizona Cardinals, Sept. 7, 2025 in New Orleans. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert, File)

FILE - Philadelphia Eagles quarterback Jalen Hurts (1) sits as they pull the blue tent over him during the NFL divisional playoff football game against the Los Angeles Rams, Jan. 19, 2025, in Philadelphia. (AP Photo/Chris Szagola, File)

Hours before that incident, the league pulled back the curtain — literally — for a small group of reporters to learn how game-day medical processes like concussion evaluations and emergency procedures work.

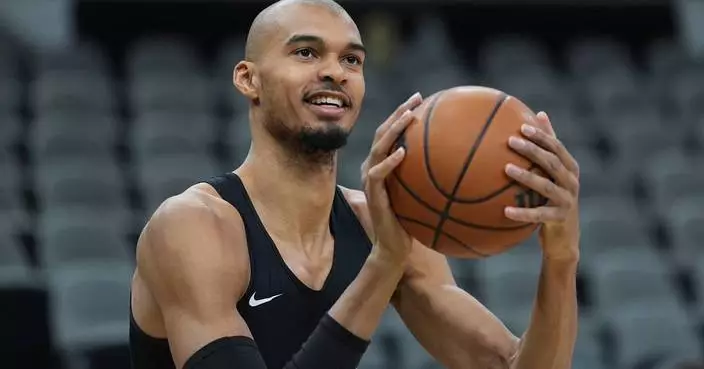

“It’s a little roomier in here than you might think,” NFL Chief Medical Officer Allen Sills said from inside the tent on Oct. 9. “Who’s usually in here? It has to be the player, the team doctor and the concussion specialist. Sometimes an athletic trainer will be here, too, but never more than those people. Never any coaches in here, never any other players in here, never anybody else in here.”

Daboll eventually apologized to the doctor at that Thursday night game for barking at him and reiterated his respect for the process, while owner John Mara — who's on the Competition Committee — put out a statement that teams "need to allow our medical staff to execute those protocols without interference.” The fiasco underscored how much of a fixture the mysterious blue tent has become in football since it was implemented in 2017 to provide a place for players to get looked at without the prying eyes of fans watching from the stands and on television.

"The stadium is a very visually distracting stadium — all of them are,” Sills said. “I really need (the player’s) concentration and our communication, right? I don’t need him looking at the replay or wondering what the score is. We want to get through this, and I find that everybody relaxes. Now we’ve gone from being in a stadium where every move is on TV, including Trevor Lawrence picking his nose the other night, to now we can just be a doctor and a patient."

Some serious injuries — like Giants wide receiver Malik Nabers tearing the ACL in his right knee — don't require a trip to the tent because a player needs to be carted off the field or sent directly inside because of what the league calls “no-go signs” like obvious symptoms of a concussion. When Buffalo safety Damar Hamlin went into cardiac arrest during a game in Cincinnati in January 2023, independent medical personnel and doctors and trainers from the Bills and Bengals sprung into action.

“At that point, there’s no Giants, there’s no Eagles,” Sills said. “We’re all out there with a life-threatening emergency, and the teams are working together.”

For injuries that are tent-worthy, there is a step-by-step procedure. It starts by making sure the player involved can't go rogue and avoid evaluation.

“We take the helmet before we even enter this room, so that way, if they try to run out, they can’t go on the field,” Giants assistant athletic trainer Justin Maher said.

Concussion evaluations can be done in a couple of minutes, Sills said, though the NFL doesn't want to rush the process — much to the chagrin of players and coaches.

“It felt so long,” Dart said that night, in large part because it wasn't his first time he was forced into the tent after scrambling and taking a big hit. “I’m tired of it, man. I’m tired of it.”

The investigation is ongoing and the league is making progress on it, executive VP of player health and safety initiatives Jeff Miller said at the fall owners meeting Tuesday in New York.

The telltale sign of whether a player is getting checked for a concussion is the presence of an unaffiliated neurotrauma consultant in a red hat.

“Here’s a pro tip for you — impress your friends and family: If you see the player coming in and somebody wearing a red hat, that is a concussion evaluation,” Sills said. "Player plus a red hat, that’s always a concussion eval. Sometimes they’ll come in here and do things that aren’t concussion eval: no red hat.”

Maher, who has been working for the Giants full time for a decade, said orthopedic exams are common. The key is getting to do it quickly without having to go behind closed doors inside.

“It kind of takes away the 80,000 fans that are watching it or even the coach or a player that’s over your shoulder,” Maher said. "Things that we do in athletic training like taping an ankle or wrapping an injury that needs to be in a more private setting — gamesmanship where you tape both ankles of a player so that the other team doesn’t know which ankle’s injured. Things like that happen in here. But it’s all medical-related, so when you see this tent up, it’s medical-related.”

Except when it isn't. Asked if the tent sometimes gets pulled up so players, coaches or staff can relieve themselves at a spot closer than the nearest restroom, Sills joked, “We will neither confirm nor deny.”

AP NFL: https://apnews.com/hub/NFL

NFL chief medical officer Allen Sills, left, and New York Giants assistant athletic trainer Justin Maher, right, stand inside a blue medical tent Thursday, Oct. 9, 2025, at MetLife Stadium in East Rutherford, N.J. (AP Photo/Stephen Whyno)

A blue medical tent is viewed Thursday, Oct. 9, 2025, at MetLife Stadium in East Rutherford, N.J. (AP Photo/Stephen Whyno)

FILE - Cincinnati Bengals quarterback Joe Burrow, center, is exits the medical tent for the locker room after suffering an injury during the second quarter of an NFL football game against the Jacksonville Jaguars, Sept. 14, 2025, in Cincinnati. (AP Photo/Kareem Elgazzar, File)

FILE - New Orleans Saints wide receiver Chris Olave (12) enters the medical tent before being examined after a hard hit in the second half of an NFL football game against the Arizona Cardinals, Sept. 7, 2025 in New Orleans. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert, File)

FILE - Philadelphia Eagles quarterback Jalen Hurts (1) sits as they pull the blue tent over him during the NFL divisional playoff football game against the Los Angeles Rams, Jan. 19, 2025, in Philadelphia. (AP Photo/Chris Szagola, File)

ATLANTA (AP) — Donald Trump would not be the first president to invoke the Insurrection Act, as he has threatened, so that he can send U.S. military forces to Minnesota.

But he'd be the only commander in chief to use the 19th-century law to send troops to quell protests that started because of federal officers the president already has sent to the area — one of whom shot and killed a U.S. citizen.

The law, which allows presidents to use the military domestically, has been invoked on more than two dozen occasions — but rarely since the 20th Century's Civil Rights Movement.

Federal forces typically are called to quell widespread violence that has broken out on the local level — before Washington's involvement and when local authorities ask for help. When presidents acted without local requests, it was usually to enforce the rights of individuals who were being threatened or not protected by state and local governments. A third scenario is an outright insurrection — like the Confederacy during the Civil War.

Experts in constitutional and military law say none of that clearly applies in Minneapolis.

“This would be a flagrant abuse of the Insurrection Act in a way that we've never seen,” said Joseph Nunn, an attorney at the Brennan Center for Justice's Liberty and National Security Program. “None of the criteria have been met.”

William Banks, a Syracuse University professor emeritus who has written extensively on the domestic use of the military, said the situation is “a historical outlier” because the violence Trump wants to end “is being created by the federal civilian officers” he sent there.

But he also cautioned Minnesota officials would have “a tough argument to win” in court, because the judiciary is hesitant to challenge “because the courts are typically going to defer to the president” on his military decisions.

Here is a look at the law, how it's been used and comparisons to Minneapolis.

George Washington signed the first version in 1792, authorizing him to mobilize state militias — National Guard forerunners — when “laws of the United States shall be opposed, or the execution thereof obstructed.”

He and John Adams used it to quash citizen uprisings against taxes, including liquor levies and property taxes that were deemed essential to the young republic's survival.

Congress expanded the law in 1807, restating presidential authority to counter “insurrection or obstruction” of laws. Nunn said the early statutes recognized a fundamental “Anglo-American tradition against military intervention in civilian affairs” except “as a tool of last resort.”

The president argues Minnesota officials and citizens are impeding U.S. law by protesting his agenda and the presence of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers and Customs and Border Protection officers. Yet early statutes also defined circumstances for the law as unrest “too powerful to be suppressed by the ordinary course” of law enforcement.

There are between 2,000 and 3,000 federal authorities in the Minneapolis-St. Paul metro area, compared to Minneapolis, which has fewer than 600 police officers. Protesters' and bystanders' video, meanwhile, has shown violence initiated by federal officers, with the interactions growing more frequent since Renee Good was shot three times and killed.

“ICE has the legal authority to enforce federal immigration laws,” Nunn said. “But what they're doing is a sort of lawless, violent behavior” that goes beyond their legal function and “foments the situation” Trump wants to suppress.

“They can't intentionally create a crisis, then turn around to do a crackdown,” he said, adding that the Constitutional requirement for a president to “faithfully execute the laws” means Trump must wield his power, on immigration and the Insurrection Act, “in good faith.”

Courts have blocked some of Trump's efforts to deploy the National Guard, but he'd argue with the Insurrection Act that he does not need a state's permission to send troops.

That traces to President Abraham Lincoln, who held in 1861 that Southern states could not legitimately secede. So, he convinced Congress to give him express power to deploy U.S. troops, without asking, into Confederate states he contended were still in the Union. Quite literally, Lincoln used the act as a legal basis to fight the Civil War.

Nunn said situations beyond such a clear insurrection as the Confederacy still require a local request or another trigger that Congress added after the Civil War: protecting individual rights. Ulysses S. Grant used that provision to send troops to counter the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacists who ignored the 14th and 15th amendments and civil rights statutes.

During post-war industrialization, violence erupted around strikes and expanding immigration — and governors sought help.

President Rutherford B. Hayes granted state requests during the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 after striking workers, state forces and local police clashed, leading to dozens of deaths. Grover Cleveland granted a Washington state governor's request — at that time it was a U.S. territory — to help protect Chinese citizens who were being attacked by white rioters. President Woodrow Wilson sent troops to Colorado in 1914 amid a coal strike after workers were killed.

Federal troops helped diffuse each situation.

Banks stressed that the law then and now presumes that federal resources are needed only when state and local authorities are overwhelmed — and Minnesota leaders say their cities would be stable and safe if Trump's feds left.

As Grant had done, mid-20th century presidents used the act to counter white supremacists.

Franklin Roosevelt dispatched 6,000 troops to Detroit — more than double the U.S. forces in Minneapolis — after race riots that started with whites attacking Black residents. State officials asked for FDR's aid after riots escalated, in part, Nunn said, because white local law enforcement joined in violence against Black residents. Federal troops calmed the city after dozens of deaths, including 17 Black residents killed by local police.

Once the Civil Rights Movement began, presidents sent authorities to Southern states without requests or permission, because local authorities defied U.S. civil rights law and fomented violence themselves.

Dwight Eisenhower enforced integration at Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas; John F. Kennedy sent troops to the University of Mississippi after riots over James Meredith's admission and then pre-emptively to ensure no violence upon George Wallace's “Stand in the Schoolhouse Door” to protest the University of Alabama's integration.

“There could have been significant loss of life from the rioters” in Mississippi, Nunn said.

Lyndon Johnson protected the 1965 Voting Rights March from Selma to Montgomery after Wallace's troopers attacked marchers' on their first peaceful attempt.

Johnson also sent troops to multiple U.S. cities in 1967 and 1968 after clashes between residents and police escalated. The same thing happened in Los Angeles in 1992, the last time the Insurrection Act was invoked.

Riots erupted after a jury failed to convict four white police officers of excessive use of force despite video showing them beating a Rodney King, a Black man. California Gov. Pete Wilson asked President George H.W. Bush for support.

Bush authorized about 4,000 troops — but after he had publicly expressed displeasure over the trial verdict. He promised to “restore order” yet directed the Justice Department to open a civil rights investigation, and two of the L.A. officers were later convicted in federal court.

President Donald Trump answers questions after signing a bill that returns whole milk to school cafeterias across the country, in the Oval Office of the White House, Wednesday, Jan. 14, 2026, in Washington. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon)