JERUSALEM (AP) — Come October, monks and nuns are busy harvesting olives at the Mount of Olives and the Gethsemane garden — where, according to the Gospel, Jesus spent the last night before being taken up the other side of the valley into Jerusalem to be crucified.

For two years, the Israel-Hamas war has cast a pall on the Holy Land. The hundreds of centuries-old olive trees here have shaken periodically in missile attacks targeting Israel.

But this year’s harvest happened as a ceasefire agreement was reached, spreading a tenuous hope for peace — peace that olive branches have symbolized since the biblical story of the dove that brought one back to Noah’s Ark to signify the end of the flood.

“The land is a gift and the sign of a divine presence,” said the Rev. Diego Dalla Gassa, a Franciscan in charge of the harvest in the hermitage next to Gethsemane. The word Gethsemane is derived from the ancient Aramaic’s and Hebrew’s “oil press.”

For Dalla Gassa and the other mostly Catholic congregations on the hill, harvesting olives to make preserves and oil is not a business or even primarily a source of sustenance for their communities. Rather, it’s a form of prayer and reverence.

“To be the custodian of holy sites doesn’t mean only to guard them, but to live them, physically but also spiritually,” he added. “It’s really the holy sites that guard us.”

Early on a recent morning, Dalla Gassa traded his habit for a T-shirt and shorts — albeit with an olive wood cross around his neck — and headed to the terraces facing Jerusalem’s Old City.

The bright sun shone off the golden dome of Al-Aqsa Mosque, visible above the walls encircling the Temple Mount — the holiest site in Judaism — alongside the bell towers of Christian churches.

Dalla Gassa and some volunteers, ranging from Israeli Jews to visiting Italian law enforcement officers, picked the black and green olives by hand and with tiny rakes, dropping them onto nets under the trees.

Once they filled a wheelbarrow, Dalla Gassa put on ear covers and got the loud, modern press humming. Soon, the fragrance of freshly pressed green oil filled the air. It takes up to 10 kilograms (22 pounds) of olives to make one liter (34 ounces) of extra-virgin oil.

Up the hill from the Franciscan convent, Sister Marie Benedicte walked among more olive trees cradling the adopted kitty she has named “Petit Chat,” little cat in French.

“It’s easy to pray while picking and nature is so beautiful,” she said later while starting her harvest. “It’s like a retreat time.”

For more than two decades, the French nun has been in the Benedictine monastery founded at the end of the 19th century atop the Mount of Olives. Only half a dozen sisters live there now, their day flowing in a 16-hour rhythm of work, contemplative walks in the garden, and prayer.

“It’s very quiet here, very simple,” said Sister Colomba, who is from the Philippines and is in charge of ensuring there’s always enough olive oil in the church lamps to keep them burning by the tabernacle.

Olive trees are an essential crop in this desert region where they’ve grown for millennia. For decades they’ve been at the heart of sometimes-violent land disputes between Palestinians and some Jewish settlers in the West Bank. Israel occupied it in the 1967 war along with east Jerusalem, where the Mount of Olives is.

The congregations on the hill do not have commercial productions, dedicating the vast majority of the oil to their own use, both in the kitchen and for sacraments. Many Christians use oil, blessed by clergy during an annual Chrism Mass, for rituals ranging from anointing the sick to blessing the baptized and new altars.

For the religious brothers and sisters living among these trees, the harvest itself is spiritual and full of symbolism.

“In picking the olives, we learn how we are picked. We go looking for that last olive — that’s what God does with us, even those who are a bit hard to reach,” said Dalla Gassa.

Squeezing a plump green olive between his fingers, he also spoke of the sacrifice that comes with fulfilling one’s vocation of love for God and neighbor.

“The olive is only good when pressed. It’s the same for us,” said Dalla Gassa.

The volunteers who’ve been harvesting this year share in the transcendent experience as much as in the dusty, hot working days.

“The garden is very special. It’s full of spirituality and holiness,” said Ilana Peer-Goldin, who on a recent morning was helping Dalla Gassa with the harvest. An Israeli raised in Jerusalem, she draws from Jewish, Catholic and Buddhist practices.

Teresa Penta, who is from Puglia, Italy — one of the Mediterranean area’s top olive-producing regions — has spent 13 years in the hermitage next to Gethsemane.

“This place has an eternal charm,” she said.

The modern olive press has been in place only a few years. She said it added special meaning, returning Gethsemane to its original function.

This year’s harvest has been meager because of drought and fierce springtime winds that damaged the blossoms. Still, other congregations have been sending their olives to be processed by the monastery of Latrun, about halfway between Jerusalem and Tel Aviv.

Latrun’s Trappist monks also have olive trees and vines, though thousands of them were destroyed by a devastating fire this spring.

Walking to the olive press outside the abbey church in his black-and-white habit, Brother Athanase said the oil and wine production helps the friars earn their living. But the end goal is different for the contemplative religious.

“To create the empty space while working with repetitive gesture, to be completely available to our Lord, Jesus Christ,” he said. “It’s a life to be received completely.”

AP journalist Melanie Lidman contributed from Tel Aviv, Israel.

Jars of preserved olives, made in past years from the harvest are stored at the Benedictine monastery's garden on the Mount of Olives, in Jerusalem, Friday, Oct. 17, 2025. (AP Photo/Oded Balilty)

Italian volunteers collect olives they just harvested at the Franciscan hermitage on the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem, Friday, Oct. 3, 2025. (AP Photo/Oded Balilty)

Freshly harvested olives are pressed at the Franciscan hermitage on the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem, Friday, Oct. 3, 2025. (AP Photo/Oded Balilty)

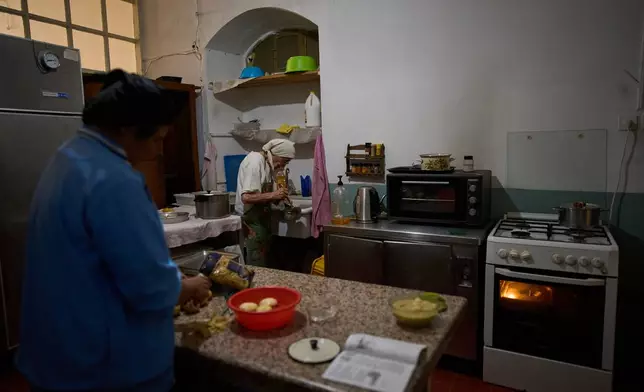

Lunch is prepared at the Benedictine monastery on top of the Mount of Olives during the olive harvest there, in Jerusalem, on Friday, Oct. 17, 2025. (AP Photo/Oded Balilty)

Italian volunteers work on the olive harvest at the Franciscan hermitage on the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem, Friday, Oct. 3, 2025. (AP Photo/Oded Balilty)

Italian volunteers work on the olive harvest at the Franciscan hermitage on the Mount of Olives with the Dome of the Rock shrine at the Al-Aqsa Mosque compound in the background, in Jerusalem, Friday, Oct. 3, 2025. (AP Photo/Oded Balilty)

Sister Marie Benedicte and Sister Colomba, two Catholic nuns, harvest olives in their monastery's garden on the Mount of Olives, in Jerusalem, Friday, Oct. 17, 2025. (AP Photo/Oded Balilty)