BOSTON (AP) — When David Arsenault takes down a worn, leather-bound 19th-century book from the winding shelves of the Boston Athenaeum, he feels a sense of awe — like he’s handling an artifact in a museum.

Many of the half a million books that line the library's seemingly endless maze of reading room shelves and stacks were printed before his great-great-grandparents were born. Among fraying copies of Charles Dickens novels, Civil War-era biographies and town genealogies, everything has a history and a heartbeat.

“It almost feels like you shouldn’t be able to take the books out of the building, it feels so special,” said Arsenault, who visits the institution adjacent to Boston Common a few times a week. “You do feel like, and in a lot of ways, you are, in a museum — but it’s a museum you get to not feel like you’re a visitor in all the time, but really a part of.”

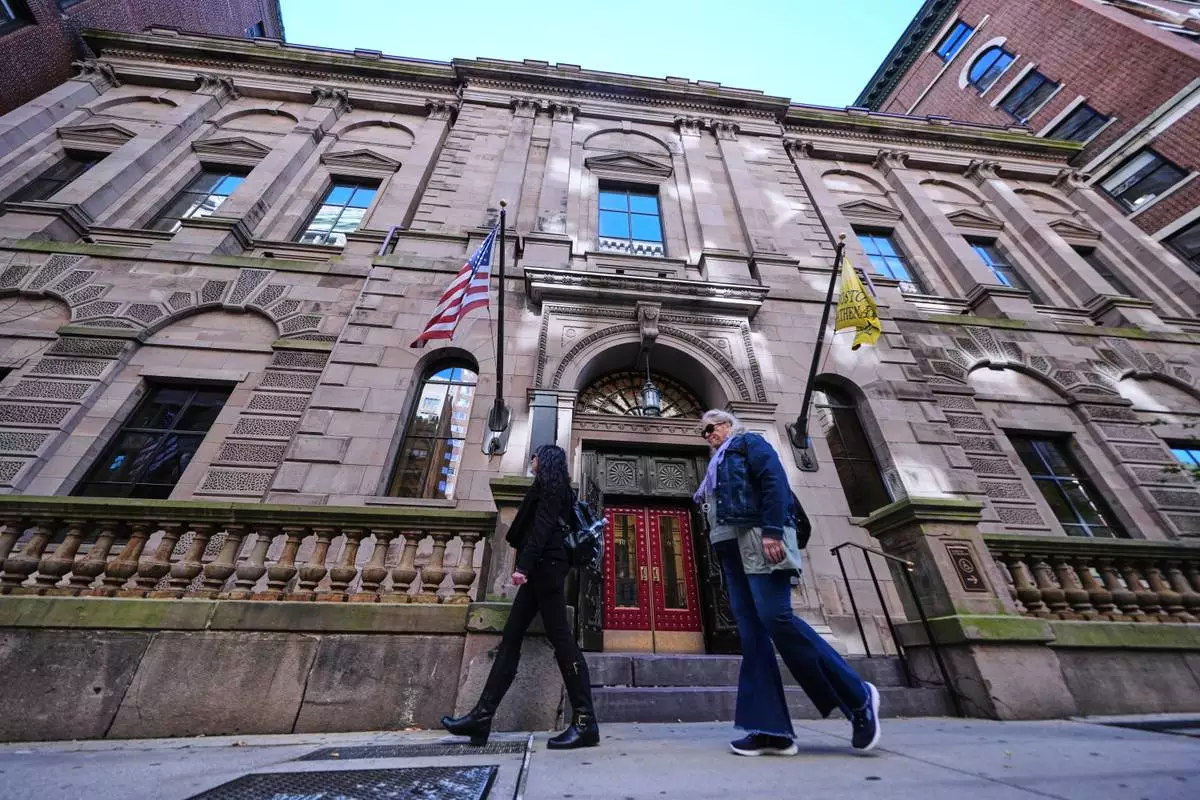

The more than 200-year-old institution is one of only about 20 member-supported private libraries in the U.S. dating back to the 18th- and 19th-centuries. Called athenaeums, a Greek word meaning “temple of Athena,” the concept predates the traditional public library most Americans recognize today. The institutions were built by merchants, doctors, writers, lawyers and ministers who wanted to not only create institutions for reading — then an expensive and difficult-to-access hobby — but also space to explore culture and debate.

Many of these athenaeums still play a vibrant role in their communities.

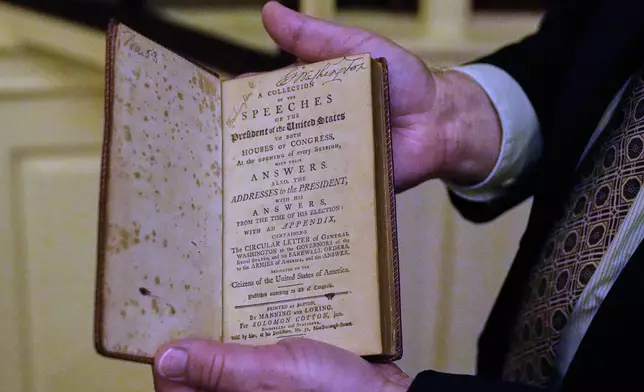

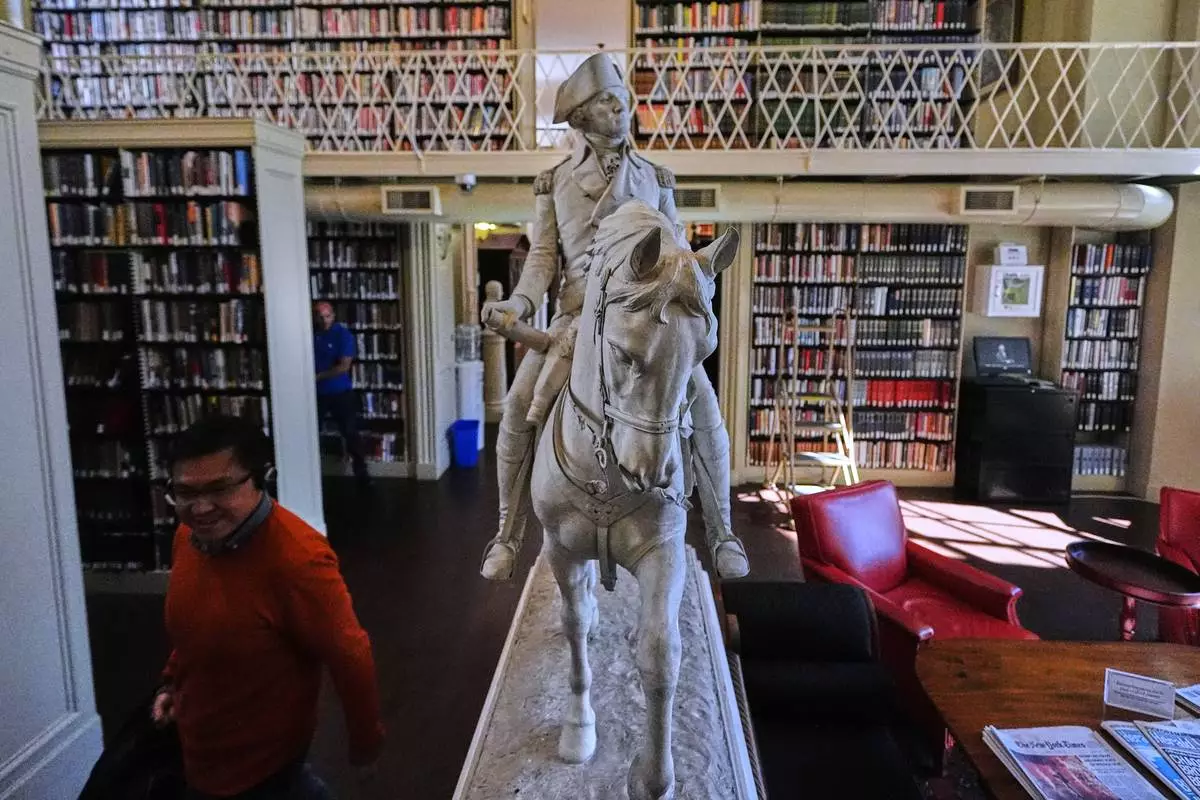

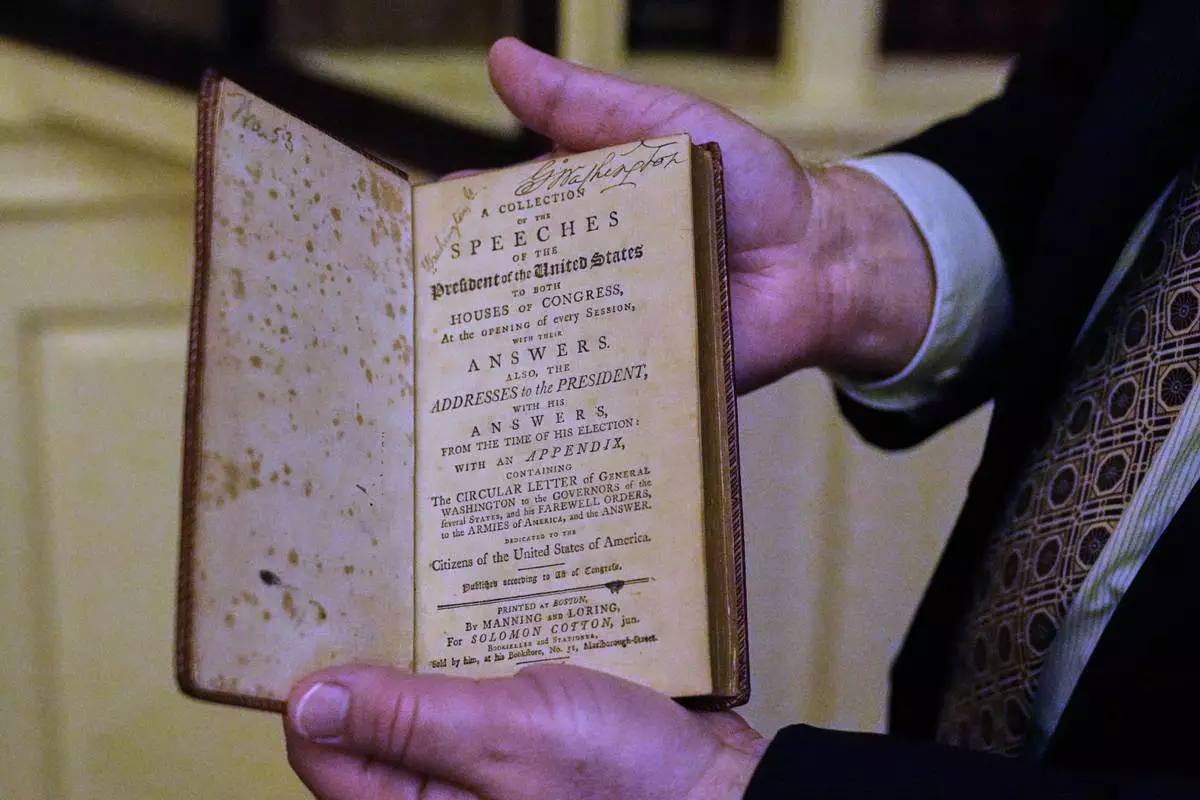

Patrons gather to play games, join discussions on James Joyce, or even research family history. Others visit to explore some of the nation’s most prized artifacts, such as the largest collection from George Washington ’s personal library at Mount Vernon at the Boston Athenaeum.

In addition to conservation work, institutions acquire and uplift the work of more modern creatives who may have been overlooked. The Boston Athenaeum recently co-debuted an exhibit by painter Allan Rohan Crite, who died in 2007 and used his canvas to depict the joy of Black life in the city.

One thing binds all athenaeums together: books and people who love them.

“The whole institution is built around housing the books,” said Matt Burriesci, executive director of Providence Athenaeum in Rhode Island. “The people who come to this institution really appreciate just holding a book in their hands and reading it the old-fashioned way.”

Built to mimic an imposing Greek temple, staffers at the Providence Athenaeum often talk about the joy of watching people enter for the first time.

Visitors must climb a series of cold, granite steps. Only then are they met with a thick wooden door that ushers them into a warm world filled with cozy reading nooks, hidden desks to leave secret messages to fellow patrons, and almost every square inch bursting with books.

“It’s the actual time capsule of people’s reading habits over 200 years,” Burriesci said, while pointing to a first-edition of Little Women, where the pages and spine proudly showcase years of being well read.

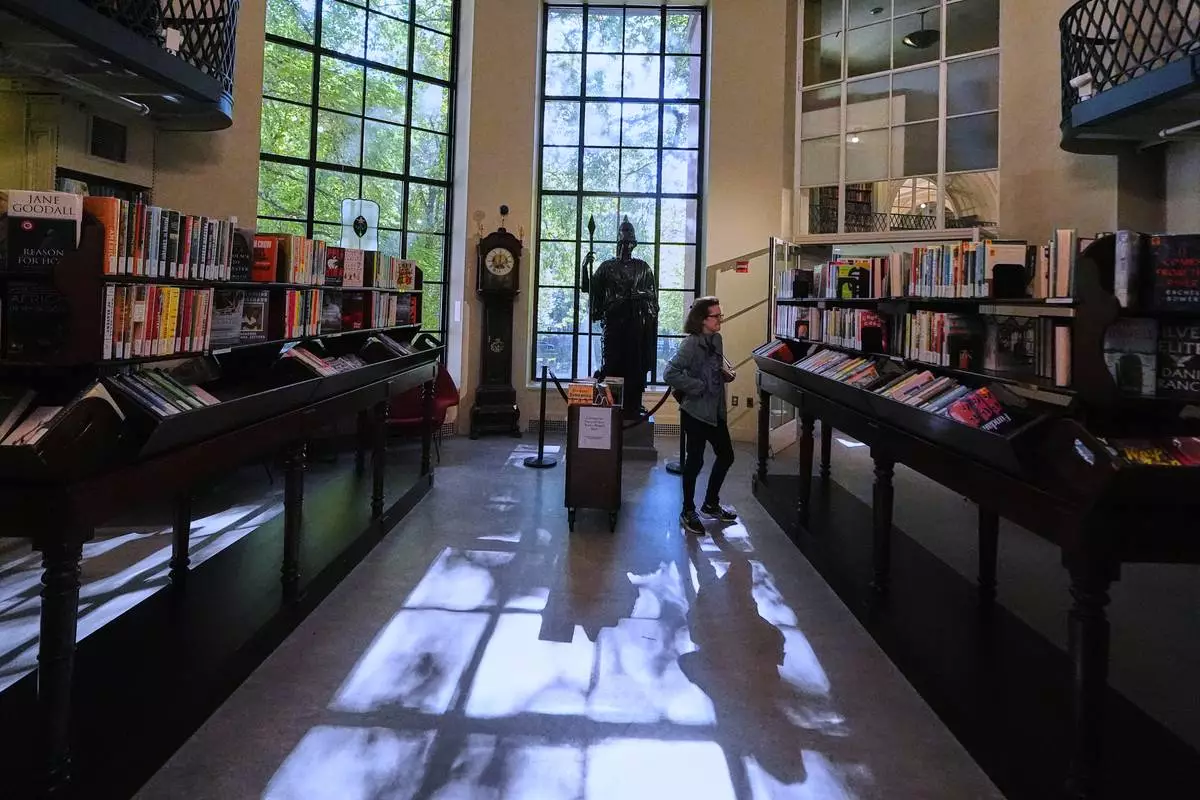

Many athenaeums are designed to pay tribute to Greek influence and their namesake, the goddess of wisdom. In Boston, a city once dubbed “the Athens of America,” visitors to the athenaeum are greeted by a nearly 7-foot-tall (2.1-meter-tall) bronze statue of Athena Giustiniani.

The building is as much an art museum as it is a library.

“So many libraries were built to be functional — this library was built to inspire,” said John Buchtel, the Boston Athenaeum’s curator of rare books and head of special collections.

The 12-level building includes five gallery floors where ornate busts of writers and historical figures decorate reading rooms with wooden tables overlooked by book-lined pathways reachable by spiral and hidden staircases.

Natural light shines in from large windows where guests can look down to see one of Boston's most historic cemeteries where figures like Paul Revere, Samuel Adams, and John Hancock are buried.

“We’re able to leave many of these things out for people to peruse, and I think people can often get curious about something and just follow their curiosity into things that they didn’t even know that they were going to be fascinated by,” said Boston Athenaeum executive director Leah Rosovsky.

When athenaeums were founded, they were exclusive spaces that only people with education and money could access.

Some are now free. Most are open to the public for day passes and tours. Memberships to the Boston Athenaeum can range from $17 to $42 a month per person, depending on whether the patron is under 40 or is sharing the membership with family members.

Charlie Grantham, a wedding photographer and aspiring novelist, said she first visited during one of the institution’s annual community days, where the public can explore for free. She said she was surprised by how accessible it was and describes the space as “Boston’s best kept secret — an oasis in the middle of the city.”

“It’s just so peaceful. Even if I’m still working... doing things I’m stressed out about at home, when I’m here, there’s like a stillness about it and things feel more manageable, things feel enjoyable here,” she said.

Some people visit every day to work remotely, read or socialize, said Salem Athenaeum executive director Jean Marie Procious.

“We do have a loneliness crisis,” she said. “And we want to encourage people to come and see us as a space to meet up with others and a safe environment that you’re not expected to buy a drink or buy a meal.”

Guests read and work at the fifth-floor reading room, designated a "silent space", at the Boston Athenaeum, Thursday, Oct. 9, 2025, in Boston. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

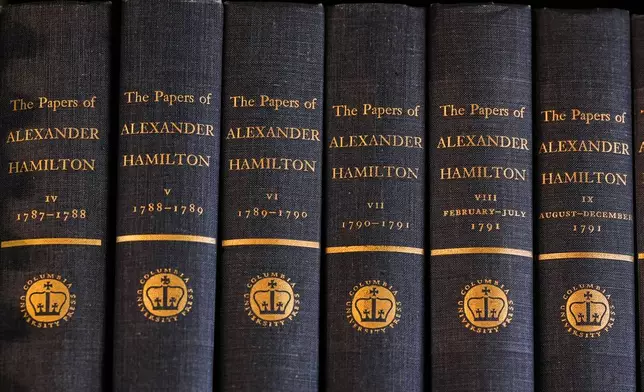

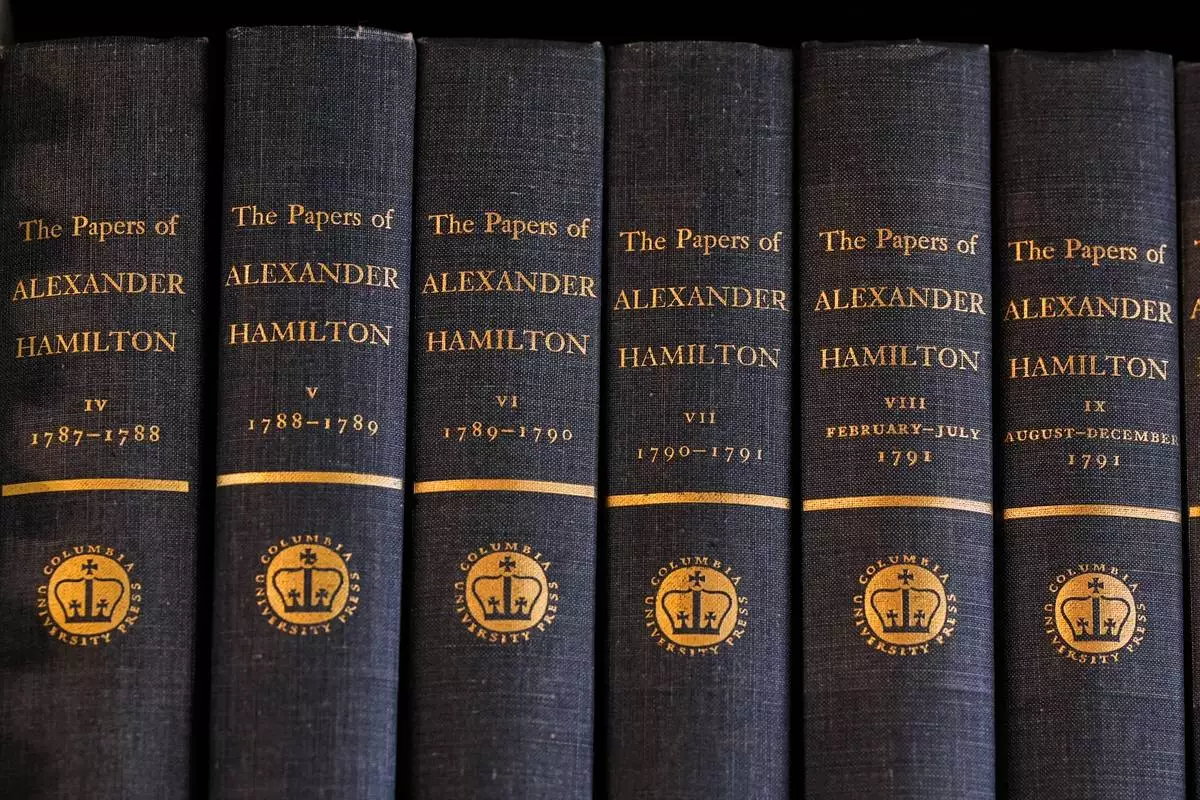

Bound copies of Alexander Hamilton's papers are displayed on a shelf at the Boston Athenaeum, a private library, Thursday, Oct. 9, 2025, in Boston. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

Little Nell, left, a sculpture of the character from Charles Dickens's "The Old Curiosity Shop", is displayed at the Boston Athenaeum, Thursday, Oct. 9, 2025, in Boston. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

Two pedestrians walk past the Boston Athenaeum, one of the oldest independent libraries in the United States, Thursday, Oct. 9, 2025, in Boston. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

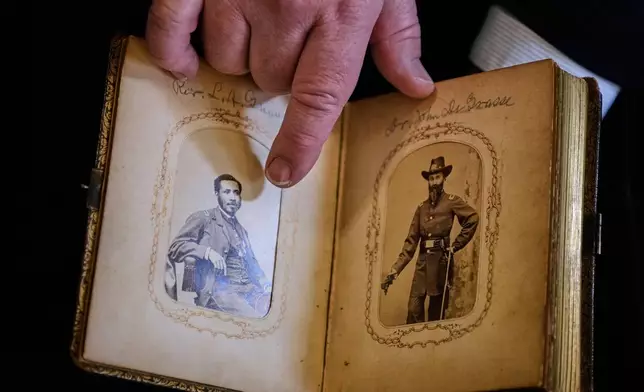

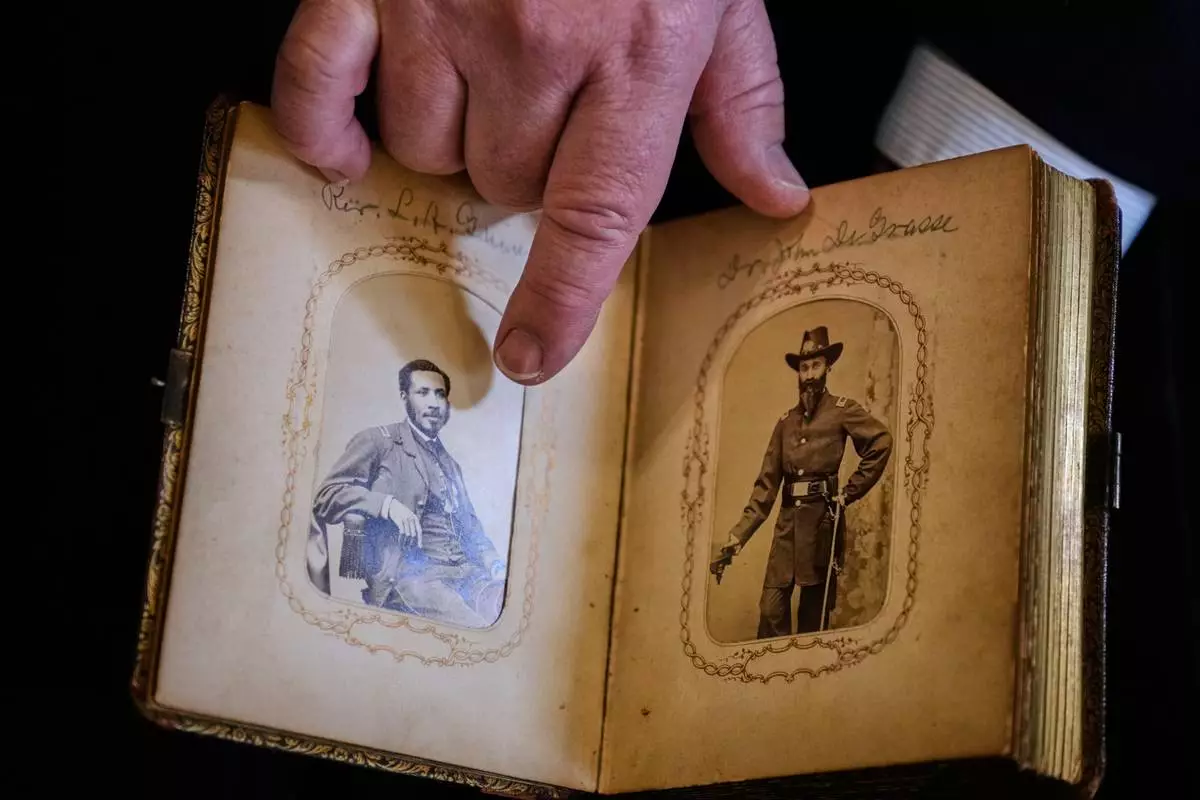

Portraits of Mass. Rep. Charles Lewis Mitchell, left, and Dr. John V. de Grasse are shown from an photograph album from the personal collection of anti-slavery activist Harriet Hayden, which was printed in the 1860's, at the Boston Athenaeum, Thursday, Oct. 9, 2025, in Boston. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

A visitor browses recent publications at the Boston Athenaeum, a private library, Thursday, Oct. 9, 2025, in Boston. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

A statue of George Washington on horseback is displayed in the private library at the Boston Athenaeum, Thursday, Oct. 9, 2025, in Boston. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

George Washington's personal copy of the 1796 book "Collection of the Speeches of the President of the United States" is shown at the Boston Athenaeum, Thursday, Oct. 9, 2025, in Boston. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

Visitors walk though the Granary Burying Ground, which includes the graves of John Hancock, Samuel Adams and Paul Revere, seen through a window at the Boston Athenaeum, Thursday, Oct. 9, 2025, in Boston. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)