TOKYO (AP) — The trial of the accused killer of former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe began Tuesday.

Tetsuya Yamagami, 45, appeared in court as U.S. President Donald Trump visits Japan for talks with new Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi. Takaichi, a conservative protege of Abe, highlighted their close ties in a meeting Tuesday with Trump, who called Abe a "great friend."

Broadcaster NHK said Yamagami pleaded guilty to the charges read by prosecutors. He appeared in a black top and gray trousers, with his long hair tied in a ponytail.

Yamagami allegedly shot Abe in 2022 with a homemade firearm during an election speech because of a grudge against the controversial Unification Church, which he believed had close ties to Abe and other Japanese politicians. He has told officials that massive donations his mother made to the church, which was founded in South Korea a year after the Korean War ended in 1953, caused his family's financial collapse.

Abe, Japan's longest-serving prime minister since World War II, is regularly mentioned by both Trump and Takaichi.

The trial in the western city of Nara is set to finish in mid-December, Kyodo news agency reported.

The Unification Church, which has powerful political connections around the world, has faced hundreds of lawsuits in Japan from families who say that it manipulated members into draining their savings to make donations. For decades, however, it largely escaped official scrutiny and maintained close links with the governing Liberal Democratic Party.

Journalists crowd as a vehicle which is belived to be carrying Tetsuya Yamagami, the accused killer of former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, arrives for a trial at the Nara District Court in Nara, western Japan Tuesday, Oct. 28, 2025. (Shohei Miyano/Kyodo News via AP)

Journalists crowd as a vehicle which is belived to be carrying Tetsuya Yamagami, the accused killer of former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, leaves a detention center in Osaka, western Japan for a trial Tuesday, Oct. 28, 2025. (Kyodo News via AP)

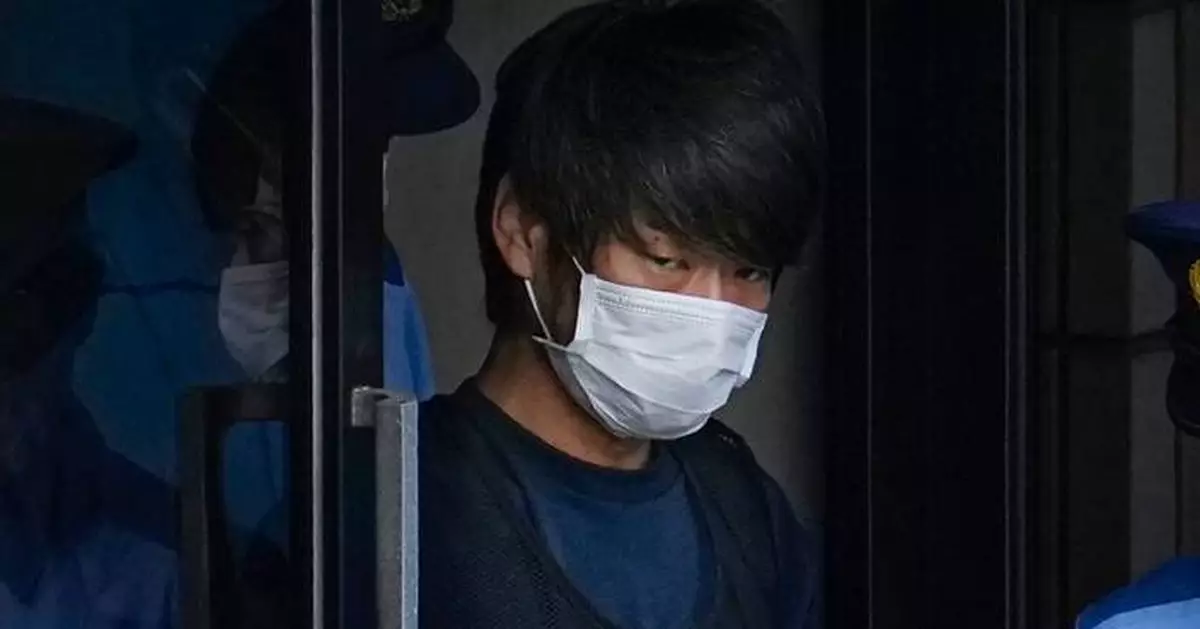

FILE - Tetsuya Yamagami, the alleged assassin of Japan's former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, gets out of a police station in Nara, western Japan, on July 10, 2022, on his way to local prosecutors' office. (Nobuki Ito/Kyodo News via AP, File)

THE HAGUE, Netherlands (AP) — Myanmar insisted Friday that its deadly military campaign against the Rohingya ethnic minority was a legitimate counter-terrorism operation and did not amount to genocide, as it defended itself at the top United Nations court against an allegation of breaching the genocide convention.

Myanmar launched the campaign in Rakhine state in 2017 after an attack by a Rohingya insurgent group. Security forces were accused of mass rapes, killings and torching thousands of homes as more than 700,000 Rohingya fled into neighboring Bangladesh.

“Myanmar was not obliged to remain idle and allow terrorists to have free reign of northern Rakhine state,” the country’s representative Ko Ko Hlaing told black-robed judges at the International Court of Justice.

African nation Gambia brought a case at the court in 2019 alleging that Myanmar's military actions amount to a breach of the Genocide Convention that was drawn up in the aftermath of World War II and the Holocaust.

Some 1.2 million members of the Rohingya minority are still languishing in chaotic, overcrowded camps in Bangladesh, where armed groups recruit children and girls as young as 12 are forced into prostitution. The sudden and severe foreign aid cuts imposed last year by U.S. President Donald Trump shuttered thousands of the camps’ schools and have caused children to starve to death.

Buddhist-majority Myanmar has long considered the Rohingya Muslim minority to be “Bengalis” from Bangladesh even though their families have lived in the country for generations. Nearly all have been denied citizenship since 1982.

As hearings opened Monday, Gambian Justice Minister Dawda Jallow said his nation filed the case after the Rohingya “endured decades of appalling persecution, and years of dehumanizing propaganda. This culminated in the savage, genocidal ‘clearance operations’ of 2016 and 2017, which were followed by continued genocidal policies meant to erase their existence in Myanmar.”

Hlaing disputed the evidence Gambia cited in its case, including the findings of an international fact-finding mission set up by the U.N.'s Human Rights Council.

“Myanmar’s position is that the Gambia has failed to meet its burden of proof," he said. "This case will be decided on the basis of proven facts, not unsubstantiated allegations. Emotional anguish and blurry factual pictures are not a substitute for rigorous presentation of facts.”

Nobel Peace Prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi represented her country at jurisdiction hearings in the case in 2019, denying that Myanmar armed forces committed genocide and instead casting the mass exodus of Rohingya people from the country she led as an unfortunate result of a battle with insurgents.

The pro-democracy icon is now in prison after being convicted of what her supporters call trumped-up charges after a military takeover of power.

Myanmar contested the court’s jurisdiction, saying Gambia was not directly involved in the conflict and therefore could not initiate a case. Both countries are signatories to the genocide convention, and in 2022, judges rejected the argument, allowing the case to move forward.

Gambia rejects Myanmar's claims that it was combating terrorism, with Jallow telling judges on Monday that “genocidal intent is the only reasonable inference that can be drawn from Myanmar’s pattern of conduct.”

In late 2024, prosecutors at another Hague-based tribunal, the International Criminal Court, requested an arrest warrant for the head of Myanmar’s military regime for crimes committed against the country’s Rohingya Muslim minority. Senior Gen. Min Aung Hlaing, who seized power from Suu Kyi in 2021, is accused of crimes against humanity for the persecution of the Rohingya. The request is still pending.

FILE - In this Sept. 7, 2017, file photo, smoke rises from a burned house in Gawdu Zara village, northern Rakhine state, where the vast majority of the country's 1.1 million Rohingya lived, Myanmar. (AP Photo, File)