As America’s aging roads fall further behind on much-needed repairs, cities and states are turning to artificial intelligence to spot the worst hazards and decide which fixes should come first.

Hawaii officials, for example, are giving away 1,000 dashboard cameras as they try to reverse a recent spike in traffic fatalities. The cameras will use AI to automate inspections of guardrails, road signs and pavement markings, instantly discerning between minor problems and emergencies that warrant sending a maintenance crew.

Click to Gallery

Chelsea Palacio, public information manager for the City of San Jose, adjusts a small detection camera – which uses AI to detect road hazards and potholes – mounted inside one of the city's parking enforcement vehicles, in San Jose, Calif., Wednesday, Nov. 12, 2025. (AP Photo/Godofredo A. Vásquez)

This City of San Jose parking enforcement vehicle is one of two equipped with a small detection camera that can detect road hazards and potholes, in San Jose, Calif., Wednesday, Nov. 12, 2025. (AP Photo/Godofredo A. Vásquez)

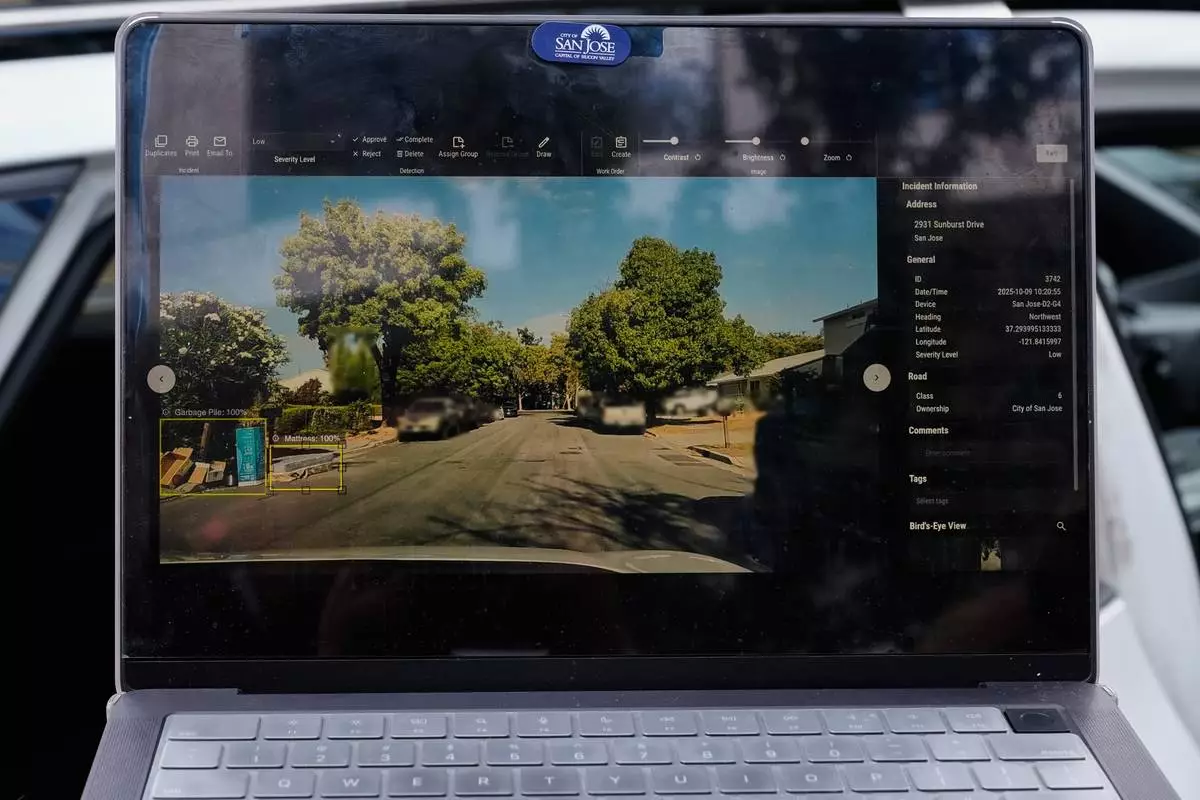

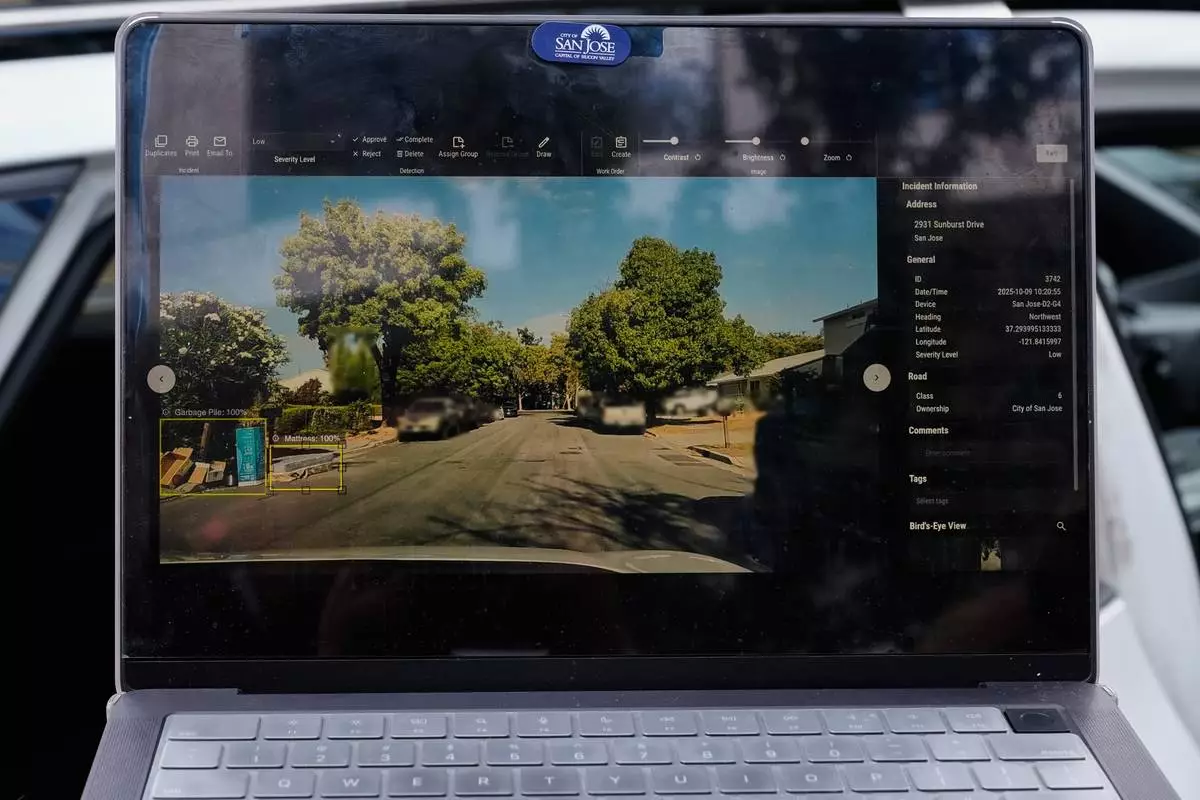

Chelsea Palacio, public information manager for the City of San Jose, showcases how a small detection camera uses AI to detect road hazards and potholes in San Jose, Calif., Wednesday, Nov. 12, 2025. (AP Photo/Godofredo A. Vásquez)

A small detection camera – which uses AI to detect road hazards and potholes – is seen mounted inside a parking enforcement vehicle, in San Jose, Calif., Wednesday, Nov. 12, 2025. (AP Photo/Godofredo A. Vásquez)

Chelsea Palacio, public information manager for the City of San Jose, showcases how a small detection camera uses AI to detect road hazards and potholes, in San Jose, Calif., Wednesday, Nov. 12, 2025. (AP Photo/Godofredo A. Vásquez)

“This is not something where it’s looked at once a month and then they sit down and figure out where they’re going to put their vans,” said Richard Browning, chief commercial officer at Nextbase, which developed the dashcams and imagery platform for Hawaii.

After San Jose, California, started mounting cameras on street sweepers, city staff confirmed the system correctly identified potholes 97% of the time. Now they're expanding the effort to parking enforcement vehicles.

Texas, where there are more roadway lane miles than the next two states combined, is less than a year into a massive AI plan that uses cameras as well as cellphone data from drivers who enroll to improve safety.

Other states use the technology to inspect street signs or build annual reports about road congestion.

Hawaii drivers over the next few weeks will be able to sign up for a free dashcam valued at $499 under the “Eyes on the Road” campaign, which was piloted on service vehicles in 2021 before being paused due to wildfires.

Roger Chen, a University of Hawaii associate professor of engineering who is helping facilitate the program, said the state faces unique challenges in maintaining its outdated roadway infrastructure.

“Equipment has to be shipped to the island,” Chen said. “There’s a space constraint and a topography constraint they have to deal with, so it’s not an easy problem.”

Although the program also monitors such things as street debris and faded paint on lane lines, the companies behind the technology particularly tout its ability to detect damaged guardrails.

“They’re analyzing all guardrails in their state, every single day,” said Mark Pittman, CEO of Blyncsy, which combines the dashboard feeds with mapping software to analyze road conditions.

Hawaii transportation officials are well aware of the risks that can stem from broken guardrails. Last year, the state reached a $3.9 million settlement with the family of a driver who was killed in 2020 after slamming into a guardrail that had been damaged in a crash 18 months earlier but never repaired.

In October, Hawaii recorded its 106th traffic fatality of 2025 — more than all of 2024. It's unclear how many of the deaths were related to road problems, but Chen said the grim trend underscores the timeliness of the dashboard program.

San Jose has reported strong early success in identifying potholes and road debris just by mounting cameras on a few street sweepers and parking enforcement vehicles.

But Mayor Matt Mahan, a Democrat who founded two tech startups before entering politics, said the effort will be much more effective if cities contribute their images to a shared AI database. The system can recognize a road problem that it has seen before — even if it happened somewhere else, Mahan said.

“It sees, ‘Oh, that actually is a cardboard box wedged between those two parked vehicles, and that counts as debris on a roadway,’” Mahan said. “We could wait five years for that to happen here, or maybe we have it at our fingertips.”

San Jose officials helped establish the GovAI Coalition, which went public in March 2024 for governments to share best practices and eventually data. Other local governments in California, Minnesota, Oregon, Texas and Washington, as well as the state of Colorado, are members.

Not all AI approaches to improving road safety require cameras.

Massachusetts-based Cambridge Mobile Telematics launched a system called StreetVision that uses cellphone data to identify risky driving behavior. The company works with state transportation departments to pinpoint where specific road conditions are fueling those dangers.

Ryan McMahon, the company's senior vice president of strategy & corporate development, was attending a conference in Washington, D.C., when he noticed the StreetVision software was showing a massive number of vehicles braking aggressively on a nearby road.

The reason: a bush was obstructing a stop sign, which drivers weren't seeing until the last second.

“What we’re looking at is the accumulation of events,” McMahon said. “That brought me to an infrastructure problem, and the solution to the infrastructure problem was a pair of garden shears."

Texas officials have been using StreetVision and various other AI tools to address safety concerns. The approach was particularly helpful recently when they scanned 250,000 lane miles (402,000 kilometers) to identify old street signs long overdue for replacement.

“If something was installed 10 or 15 years ago and the work order was on paper, God help you trying to find that in the digits somewhere,” said Jim Markham, who deals with crash data for the Texas Department of Transportation. “Having AI that can go through and screen for that is a force multiplier that basically allows us to look wider and further much faster than we could just driving stuff around.”

Experts in AI-based road safety techniques say what's being done now is largely just a stepping stone for a time when a large proportion of vehicles on the road will be driverless.

Pittman, the Blyncsy CEO who has worked on the Hawaii dashcam program, predicts that within eight years almost every new vehicle — with or without a driver — will come with a camera.

“How do we see our roadways today from the perspective of grandma in a Buick but also Elon and his Tesla?” Pittman said. “This is really important nuance for departments of transportation and city agencies. They're now building infrastructure for humans and automated drivers alike, and they need to start bridging that divide.”

Chelsea Palacio, public information manager for the City of San Jose, adjusts a small detection camera – which uses AI to detect road hazards and potholes – mounted inside one of the city's parking enforcement vehicles, in San Jose, Calif., Wednesday, Nov. 12, 2025. (AP Photo/Godofredo A. Vásquez)

This City of San Jose parking enforcement vehicle is one of two equipped with a small detection camera that can detect road hazards and potholes, in San Jose, Calif., Wednesday, Nov. 12, 2025. (AP Photo/Godofredo A. Vásquez)

Chelsea Palacio, public information manager for the City of San Jose, showcases how a small detection camera uses AI to detect road hazards and potholes in San Jose, Calif., Wednesday, Nov. 12, 2025. (AP Photo/Godofredo A. Vásquez)

A small detection camera – which uses AI to detect road hazards and potholes – is seen mounted inside a parking enforcement vehicle, in San Jose, Calif., Wednesday, Nov. 12, 2025. (AP Photo/Godofredo A. Vásquez)

Chelsea Palacio, public information manager for the City of San Jose, showcases how a small detection camera uses AI to detect road hazards and potholes, in San Jose, Calif., Wednesday, Nov. 12, 2025. (AP Photo/Godofredo A. Vásquez)

Long security lines snaked into baggage claim areas and parking garages at some U.S. airports this weekend, a possible indicator of more widespread travel problems as the latest government shutdown drags on.

That kind of disruption, while not yet widespread, is not a concern that typically surfaces at San Francisco International Airport, the largest of nearly two dozen U.S. airports where screening checkpoints are staffed by private contractors under a little-used federal program that allows airports to outsource security screenings while maintaining TSA oversight.

Because contractors' pay comes from a federal contract, it often continues even when the government shuts down.

“The money’s already been allocated, the payments have already been made, and that continues without interruption,” SFO spokesperson Doug Yakel told The Associated Press. “That is a very nice place to be.”

The contrast draws attention to a long-running debate in the aviation industry: Can private contractors operating under TSA oversight provide a stopgap — and shield airport security operations from the political impasses that can disrupt U.S. air travel?

Some aviation experts see the TSA screening program as a potential model for keeping security lines moving with fewer disruptions during shutdowns. At SFO, that system helped maintain screening operations during last year's record 43-day shutdown, Yakel said.

But critics caution that privatization is not a silver bullet and could introduce new risks. The union representing federal screeners argues that moving operations to private companies could erode job protections and reduce pay and benefits for workers already facing high turnover amid demanding conditions.

Established in 2004, TSA’s screening partnership program allows airports to use private security companies chosen by the federal government to run checkpoints while TSA retains authority over procedures and oversight. The agency says private screeners receive the same security background checks as their federal counterparts.

The program “provides needed relief to staffing shortages brought on by a government shutdown," TSA said in a statement to AP.

In addition to SFO, other participating airports include Kansas City International Airport, Atlantic City International Airport and Orlando Sanford International Airport.

The vast majority of the nation’s roughly 400 commercial airports, meanwhile, rely on federal screening officers employed directly by TSA. During shutdowns, those workers must continue reporting for duty even though they stop getting paid — a dynamic that has historically led to higher absenteeism and slower-moving checkpoints the longer a shutdown lasts.

The current partial shutdown affects only the Department of Homeland Security, which includes TSA. Democrats in Congress refused to fund the department over objections to its immigration enforcement tactics. The lapse marks the third shutdown in less than a year to leave TSA workers temporarily without pay — and once the government reopens, to have to wait for backpay.

Those disruptions can ripple through the travel system, cascading problems across already crowded flight schedules. The strain is especially acute this time of year as airlines and airports brace for what they expect will be one of the busiest spring break travel seasons on record.

Aviation security expert Sheldon Jacobson, whose research contributed to the design of TSA PreCheck, said the program’s success at SFO, a large international airport, shows that privatization “is something that needs to be explored.”

SFO is among the top 15 busiest airports in the U.S. when measured by passenger traffic. A major hub for international travel, it is the second-busiest airport in California behind Los Angeles International Airport.

“It’s operated just as well as any other airport,” Jacobson said, adding that SFO’s multiple concourses and status as a hub for United Airlines demonstrate that even large-scale operations can be managed effectively under this model. “If SFO is the litmus test for delivering this privatized product, then many other airports can do it, too.”

Jacobson noted that most airports currently using the program are smaller, but “the scale issue should not be a limiting factor,” and he called for a broader conversation on how such options could deliver government services efficiently and benefit travelers.

“Of course TSA would have oversight. It’s not like they’re freewheeling on their own,” he said of privately contracted screeners. “We might as well use a government shutdown that affects air travel as an opportunity to begin that discussion.”

The American Federation of Government Employees, which represents TSA officers, has long opposed privatization.

“We will never advocate for any privatization of any federal employees. We don’t believe that’ll work,” Johnny Jones, secretary-treasurer of the TSA union’s bargaining unit, said in a brief phone call this week.

In a blog post on its website, the union argues it could weaken accountability for aviation security — one of the reasons Congress chose to federalize airport screening after the Sept. 11 attacks.

The union also warned that private companies could face pressure to cut costs in ways that affect training, staffing levels and employee benefits. Relying on contractors, the union says, could create inconsistencies between airports if different companies operate checkpoints across the country, potentially complicating oversight of a system designed to maintain uniform national security standards.

“We have to remember the TSA was created in the wake of 9/11 when there were no security standards or very minimal security standards,” said airline industry analyst Henry Harteveldt, president of Atmosphere Research Group. “The TSA came around, they established very stringent airport screening security requirements, which exist to this day.”

Others say there are simpler ways to address the shutdown problem.

Industry groups — including the U.S. Travel Association, Airlines for America and the American Association of Airport Executives — are urging Congress to pass legislation that would ensure aviation workers are paid regardless of the government's funding status.

“Every time Washington fails to fund the government, these essential workers pay the price. So do travelers. So does the economy,” Geoff Freeman, U.S. Travel Association's president, said in a statement. “That is why America’s travel industry has come together, because this workforce is too important, and the stakes are too high, for this to keep happening.”

Republican lawmakers have pushed in recent years to dismantle the agency entirely. Last year, two GOP senators introduced the “Abolish TSA Act,” which would phase out the agency and transfer oversight to a new office charged with aviation security. Supporters of the long-shot legislation say privatized screening could be more efficient and less vulnerable to shutdowns.

TSA leadership has signaled an openness to discussion. Speaking at a House Appropriations subcommittee hearing last year, Ha Nguyen McNeill, a senior official performing the duties of TSA administrator, said “nothing is off the table” regarding potential privatization.

“If a new privatization scheme makes sense, then we’re happy to have that discussion to see what we can come up with,” McNeill said. “It's not an all-or-nothing game.”

At SFO, officials say its screening model was adopted more than 20 years ago for reasons unrelated to government shutdowns. But with shutdowns in recent years growing longer and more disruptive, the airport says its arrangement has revealed an unintended benefit: fewer staffing disruptions at checkpoints.

“The benefits, I think, are compelling,” Harteveldt said. “The real issue is making sure that any vendor, any partner to the TSA, upholds the strict standards that TSA has established and works with TSA to ensure that screening remains efficient and finds ways to make it even better.”

Associated Press video journalist Haven Daley contributed from San Francisco.

A Covenant Aviation Security Private Security Services agent checks in a passenger at a security gate at San Francisco International Airport in San Francisco, Friday, Feb. 27, 2026. (AP Photo/Jeff Chiu)

Covenant Aviation Security Private Security Services agents check in passengers at a security gate at San Francisco International Airport in San Francisco, Friday, Feb. 27, 2026. (AP Photo/Jeff Chiu)

A Covenant Aviation Security Private Security Services agent checks the identifcation of a passenger at a security gate at San Francisco International Airport in San Francisco, Friday, Feb. 27, 2026. (AP Photo/Jeff Chiu)

Covenant Aviation Security Private Security Services agents check in passengers at a security gate at San Francisco International Airport in San Francisco, Friday, Feb. 27, 2026. (AP Photo/Jeff Chiu)

A Covenant Aviation Security Private Security Services patch is shown on an agent at San Francisco International Airport in San Francisco, Friday, Feb. 27, 2026. (AP Photo/Jeff Chiu)