MELBOURNE, Australia (AP) — Three Christian extremists shared a delusional disorder when they opened fire on police officers they perceived as “demons intent on killing them” on a rural Australian property three years ago, a coroner found on Friday.

The extremists — brothers Gareth and Nathaniel Train and Gareth’s wife, Stacey Train -- were among six people killed in a six-hour gunbattle that began on Dec. 12, 2022, in the sparsely populated Wieambilla region west of the Queensland state capital, Brisbane.

The trio killed two police officers, Rachel McCrow and Matthew Arnold, and a neighbor, Alan Dare, who had come to investigate scrub fires the Trains had ignited.

Four police officers had come to Gareth and Stacey Train’s home in response to a missing persons report for Nathaniel Train, who had been a school principal in neighboring New South Wales state.

State Coroner Terry Ryan on Friday accepted psychiatric evidence that the Trains “each had an undiagnosed and untreated psychotic illness. A shared delusional disorder.”

The disorder began with Gareth Train, the older brother. All three believed the world was about to end in accordance with Christian teachings.

“They were psychotically unwell and driven by their persecutory beliefs. I consider that Gareth, Stacey and Nathaniel were from the time the Queensland Police Service officers entered their property intent on killing the officers and, if necessary, intent on dying rather than being taken into custody,” Ryan said.

“I accept that while End of Times religious themes became central to their beliefs system, their psychotic disorder was underpinned by broader persecutory beliefs including that the government was evil and that police officers, including the police officers who attended at their property … were demons intent on killing them,” he added.

Ryan had heard medical evidence, during a 17-day inquiry hearing last year, that shared delusional disorders were exceptionally rare.

The coroner rejected a contrary psychiatric opinion that the Trains’ ambush was an act of terrorism as defined by Australian law with the intention of intimidating the Queensland government and police.

Australian law defines a terrorist act as an action or threat made with the intention of advancing a political, religious, or ideological cause to coerce a government or intimidate the public.

“Rather I consider they were acting defensively within their delusional framework to defend themselves and their property from what they regarded was an evil advance on them,” Ryan said.

“The Trains’ beliefs, although wrong, meant they posed an extreme risk of danger to any police officer or other authority figure who might have attended their property,” Ryan added.

The Train brothers opened fire with bolt-action rifles from concealed sniper positions within two minutes of the four police officers stepping on to their property.

Nathaniel Train killed Arnold first, then his brother killed McCrow.

Officer Randal Kirk was wounded as he fled. A fourth officer, Keely Brough, hid in scrub on the property for around two hours before police reinforcements arrived.

The police Glock pistols did not have the range or accuracy of the Trains’ high-powered rifles.

“Once the shooting commenced, the officers’ Glocks were woefully inadequate for the purpose of defending themselves or each other from the attack they faced,” Ryan said.

The coroner said he was not satisfied that wearing armored vests could have prevented the two police officers' deaths.

He also rejected a submission made by Dare family lawyers that police had caused Alan Dare's death by failing to advise his wife when she called to report smoke that there were active shooters in the area.

Ryan found “at least some” of the Trains’ weapons had been obtained lawfully under Australia’s relatively tough gun ownership laws.

He recommended the Queensland government consider introducing mandatory mental health assessments for people who apply for gun licenses.

The coroner also recommended police consider using drones to make risk assessments in rural and remote locations like Wieambilla before sending officers in on foot, and that additional funding for the Queensland Fixated Threat Assessment Center that monitors fixated and grievance-fueled individuals.

“It is concerning that the online activities of Gareth Train in the years leading up to Dec. 12, 2022, carried out in plain sight, did not appear to have been monitored or drawn to the attention of law enforcement agencies,” Ryan said.

FILE - In this undated photo provided by the Queensland Department of Justice and Attorney-General, a rifle lays on a log and a pistol is on a near-by table at a rural property in Wieambilla, Australia. (Queensland Department of Justice and Attorney-General via AP, File)

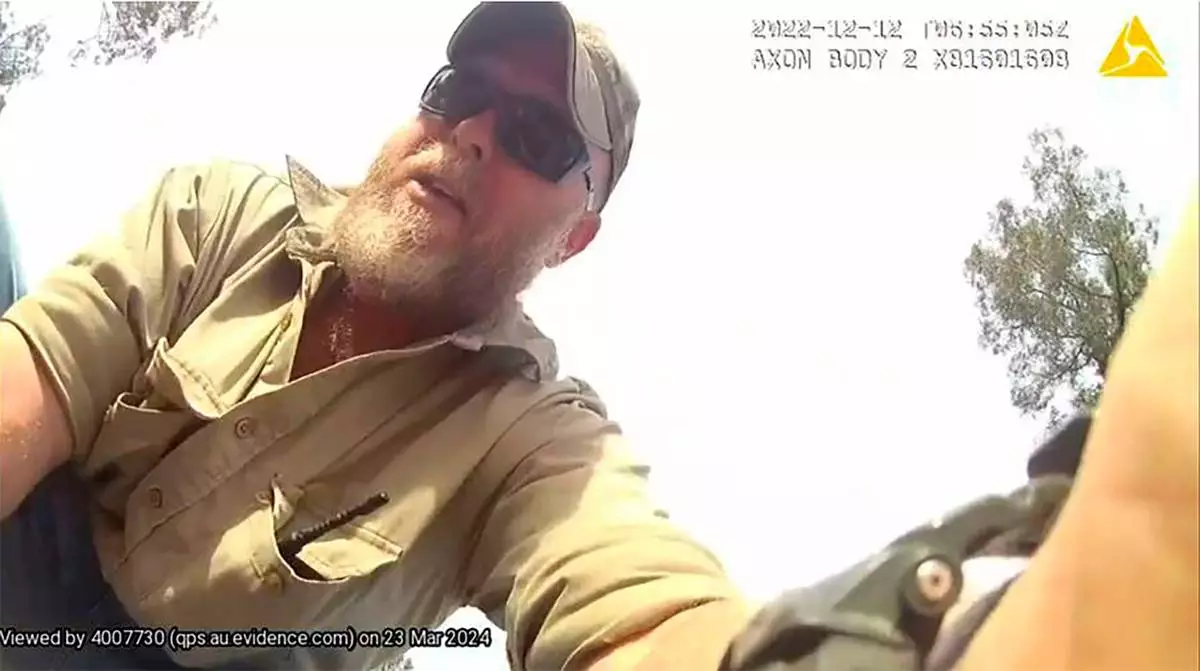

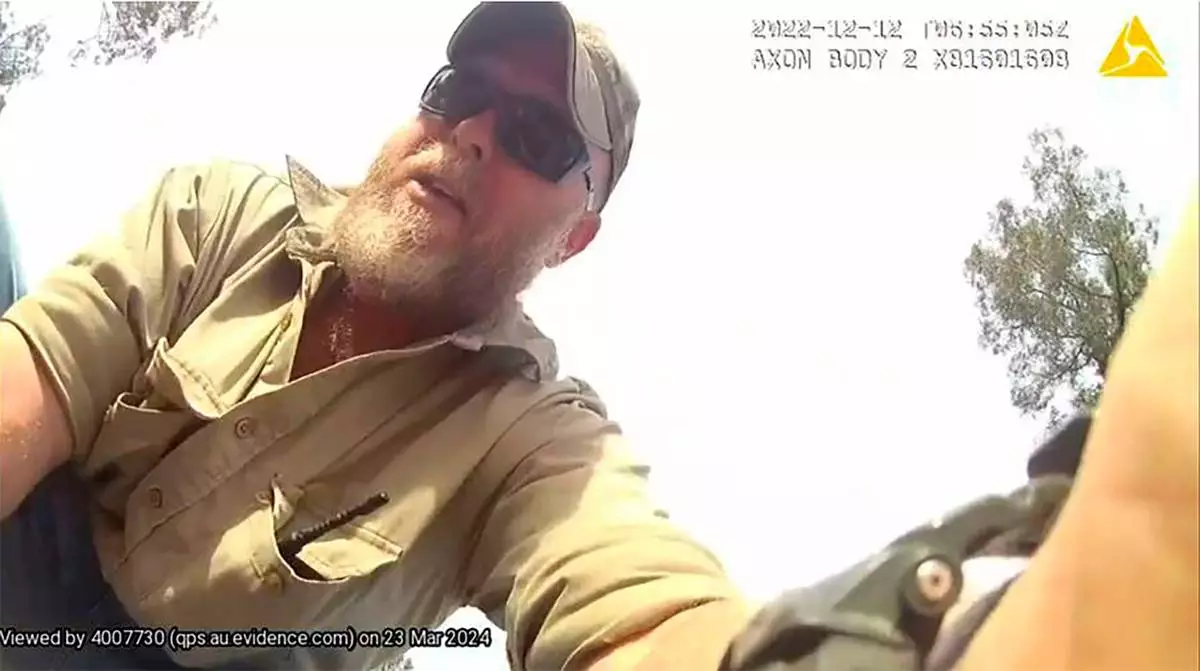

FILE - In this photo provided by the Queensland Department of Justice and Attorney-General, conspiracy theorists Gareth Train is recorded by a police body camera on Dec. 12, 2022, at a rural property in Wieambilla, Australia. (Queensland Department of Justice and Attorney-General via AP, File)

HOMS, Syria (AP) — A year ago, Mohammad Marwan found himself stumbling, barefoot and dazed, out of Syria’s notorious Saydnaya prison on the outskirts of Damascus as rebel forces pushing toward the capital threw open its doors to release the prisoners.

Arrested in 2018 for fleeing compulsory military service, the father of three had cycled through four other lockups before landing in Saydnaya, a sprawling complex just north of Damascus that became synonymous with some of the worst atrocities committed under the rule of now-ousted President Bashar Assad.

He recalled guards waiting to welcome new prisoners with a gauntlet of beatings and electric shocks. “They said, ‘You have no rights here, and we’re not calling an ambulance unless we have a dead body,’” Marwan said.

His Dec. 8, 2024, homecoming to a house full of relatives and friends in his village in Homs province was joyful.

But in the year since then, he has struggled to overcome the physical and psychological effects of his six-year imprisonment. He suffered from chest pain and difficulty breathing that turned out to be the result of tuberculosis. He was beset by crippling anxiety and difficulty sleeping.

He’s now undergoing treatment for tuberculosis and attending therapy sessions at a center in Homs focused on rehabilitating former prisoners, and Marwan said his physical and mental situations have gradually improved.

“We were in something like a state of death” in Saydnaya, he said. “Now we’ve come back to life.”

On Monday, thousands of Syrians took to the streets to celebrate the anniversary of Assad's fall.

Like Marwan, the country is struggling to heal a year after the Assad dynasty’s repressive 50-year reign came to an end following 14 years of civil war that left an estimated half a million people dead, millions more displaced, and the country battered and divided.

Assad's downfall came as a shock, even to the insurgents who unseated him. In late November 2024, groups in the country’s northwest — led by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, an Islamist rebel group whose then-leader, Ahmad al-Sharaa, is now the country’s interim president — launched an offensive on the city of Aleppo, aiming to take it back from Assad’s forces.

They were startled when the Syrian army collapsed with little resistance, first in Aleppo, then the key cities of Hama and Homs, leaving the road to Damascus open. Meanwhile, insurgent groups in the country’s south mobilized to make their own push toward the capital.

The rebels took Damascus on Dec. 8 while Assad was whisked away by Russian forces and remains in exile in Moscow. But Russia, a longtime Assad ally, did not intervene militarily to defend him and has since established ties with the country's new rulers and maintained its bases on the Syrian coast.

Hassan Abdul Ghani, spokesperson for Syrian Ministry of Defense, said HTS and its allies had launched a major organizational overhaul after Assad’s forces regained control of a number of formerly rebel-controlled areas in 2019 and 2020.

The rebel offensive in November 2024 was not initially aimed at seizing Damascus but was meant to preempt an expected major offensive by Assad’s forces in opposition-held Idlib intending to “finish the Idlib file,” Abdul Ghani said.

Launching an attack on Aleppo “was a military solution to expand the radius of the battle and thus safeguard the liberated interior areas," he said.

In timing the attack, the insurgents also took advantage of the fact that Russia was distracted by its war in Ukraine and that the Iran-backed Lebanese militant group Hezbollah, another Assad ally, was licking its wounds after a damaging war with Israel.

When the Syrian army’s defenses collapsed, the rebels pressed on, “taking advantage of every golden opportunity,” Abdul Ghani said.

Since his sudden ascent to power, al-Sharaa has launched a diplomatic charm offensive, building ties with Western and Arab countries that shunned Assad and that once considered al-Sharaa a terrorist.

In November, he became the first Syrian president since the country’s independence in 1946 to visit Washington.

But the diplomatic successes have been offset by outbreaks of sectarian violence in which hundreds of civilians from the Alawite and Druze minorities were killed by pro-government Sunni fighters. Local Druze groups have now set up their own de facto government and military in the southern Sweida province.

There are ongoing tensions between the new government in Damascus and Kurdish-led forces controlling the country’s northeast, despite an agreement inked in March that was supposed to lead to a merger of their forces.

Israel is wary of Syria's new Islamist-led government even though al-Sharaa has said he wants no conflict with the country. Israel has seized a formerly U.N.-patrolled buffer zone in southern Syria and launched regular airstrikes and incursions since Assad’s fall. Negotiations for a security agreement have stalled.

Remnants of the civil war are everywhere. The Mines Advisory Group reported Monday that at least 590 people have been killed by landmines in Syria since Assad’s fall, including 167 children, putting the country on track to record the world’s highest landmine casualty rate in 2025.

Meanwhile, the economy has remained sluggish, despite the lifting of most Western sanctions. While Gulf countries have promised to invest in reconstruction projects, little has materialized on the ground. The World Bank estimates that rebuilding the country’s war-damaged areas will cost $216 billion.

The rebuilding that has taken place has largely been individual owners paying to fix their own damaged houses and businesses.

On the outskirts of Damascus, the once-vibrant Yarmouk Palestinian camp today largely resembles a moonscape. Taken over by a series of militant groups then bombarded by government planes, the camp was all but abandoned after 2018.

Since Assad’s fall, a steady stream of former residents have come back.

The most damaged areas remain largely deserted but on the main street leading into the camp, bit by bit, blasted-out walls have been replaced in the buildings that remain structurally sound. Shops have reopened and families have come back to their apartments. But any larger reconstruction initiative appears to still be far off.

“It’s been a year since the regime fell. I would hope they could remove the old destroyed houses and build towers,” said Maher al-Homsi, who is fixing his damaged home to move back, although the area doesn't even have a water connection.

His neighbor, Etab al-Hawari, was willing to cut the new authorities some slack.

“They inherited an empty country — the banks are empty, the infrastructure was robbed, the homes were robbed," she said.

Bassam Dimashqi, a dentist from Damascus, said of the country after Assad’s fall, “Of course it’s better, there’s freedom of some sort.”

But he remains anxious about the precarious security situation and its economic impacts.

“The job of the state is to impose security, and once you impose security, everything else will come," he said. "The security situation is what encourages investors to come and do projects.”

The U.N refugee agency reports that more than 1 million refugees and nearly 2 million internally displaced Syrians have returned to their homes since Assad’s fall. But without jobs and reconstruction, some will leave again.

Among them is Marwan, the former prisoner, who says the post-Assad situation in Syria is “far better” than before. But he is struggling economically.

Sometimes he picks up labor that pays only 50,000 or 60,000 Syrian pounds daily, the equivalent of about $5.

Once he finishes his tuberculosis treatment, he said, he plans to leave to Lebanon in search of better-paid work.

Sewell reported from Beirut. Associated Press journalist Omar Albam in Damascus contributed to this report.

FILE - A man breaks the lock of a cell in the infamous Saydnaya military prison, just north of Damascus, Syria, Monday, Dec. 9, 2024. (AP Photo/Hussein Malla, File)

Former detainee Mohammad Marwan walks down a street on his way to the Homs Recovery Center in the village of Tell Dahab in the Homs countryside, Syria, Tuesday, Dec. 2, 2025. (AP Photo/Ghaith Alsayed)

A girl sits on a machine gun as visitors tour the "Syrian Revolution Military Exhibition," which opened last week ahead of the first anniversary of the ousting of the Bashar Assad regime in Damascus, Syria, Sunday, Dec. 7, 2025. (AP Photo/Ghaith Alsayed)

A boy checks out military equipment as visitors tour the "Syrian Revolution Military Exhibition," which opened last week ahead of the first anniversary of the ousting of the Bashar Assad regime in Damascus, Syria, Sunday, Dec. 7, 2025. (AP Photo/Ghaith Alsayed)

A Syrian man silhouetted by a digital billboard showing the date of the ousting of the Bashar Assad regime during celebrations marking the first anniversary, in Damascus , Syria, Sunday, Dec. 7, 2025. The Arabic words read: "A history retold and a bond renewed." (AP Photo/Hussein Malla)

Wanted portraits of former Syrian president Bashar Assad are displayed in the window of a coffeeshop, in Damascus Sunday, Dec. 7, 2025, as Syrians celebrate marking the first anniversary of the ousting of the Bashar Assad regime. (AP Photo/Hussein Malla)

Syrian men wearing anonymous masks flash victory signs, as they stand on top of their car with its front window covered by an Islamic flag, during celebrations marking the first anniversary of the ousting of the Bashar Assad regime in Damascus, Sunday, Dec. 7, 2025. (AP Photo/Hussein Malla)