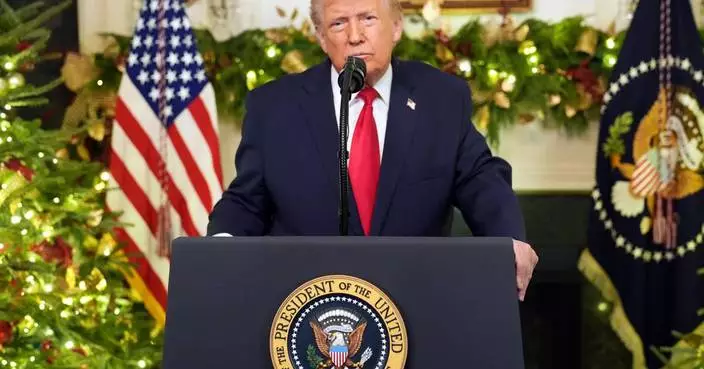

WASHINGTON (AP) — The Justice Department has launched a months-long effort to prosecute people accused of assaulting or hindering federal officers while protesting President Donald Trump’s immigration crackdown and military deployments. Attorney General Pam Bondi has vowed such offenders will face “severe consequences.”

In a review of scores of criminal prosecutions brought by federal prosecutors, The Associated Press found that the Justice Department has struggled to deliver on Bondi's pledge.

Click to Gallery

FILE - California National Guard are positioned at the Federal Building on Tuesday, June 10, 2025, in downtown Los Angeles. (AP Photo/Eric Thayer, File)

FILE - Police and federal officers deploy gas canisters to disperse protesters near a U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement facility in Portland, Ore. on Oct. 5, 2025. (AP Photo/Ethan Swope, File)

Katherine Carreño stands for a portrait Saturday, Dec. 6, 2025, in Los Angeles. (AP Photo/Allison Dinner)

FILE - A protester is detained outside the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement facility on Sunday, Oct. 12, 2025, in Portland, Ore. (AP Photo/Jenny Kane, File)

Katherine Carreño stands for a portrait Saturday, Dec. 6, 2025, in Los Angeles. (AP Photo/Allison Dinner)

An analysis of 166 federal criminal cases brought since May against people in four Democratic-led cities at the epicenter of demonstrations found that aggressive charging decisions and rhetoric painting defendants as domestic terrorists have frequently failed to hold up in court.

“It’s clear from this data that the government is being extremely aggressive and charging for things that ordinarily wouldn’t be charged at all,” said Mary McCord, a former federal prosecutor who is the director of Georgetown University Law Center’s Institute for Constitutional Advocacy. “They appear to want to chill people from protesting against the administration’s mass deportation plans.”

Here are some key findings from the AP's analysis:

Of 100 people initially charged with felony assaults on federal agents, 55 saw their charges reduced to misdemeanors, or dismissed.

Sometimes prosecutors failed to win grand jury indictments required to prosecute someone on a felony, the AP found. Videos and testimony called into question some of the initial allegations, resulting in prosecutors downgrading offenses.

In dozens of cases, officers suffered minor or no injuries, undercutting a key component of the felony assault charge that requires the potential for serious bodily harm.

One of the cases was against Dana Briggs, a 70-year-old Air Force veteran charged in September with assault after a protest in Chicago. After video footage emerged of federal agents knocking Briggs to the ground, prosecutors dropped a case they had already reduced to a misdemeanor.

Another case dropped by prosecutors was against 28-year-old Lucy Shepherd, who was charged with felony assault after she batted away the arm of a federal officer who was attempting to clear a crowd outside Portland’s Immigration and Customs Enforcement facility. Her lawyers argued a video of her arrest showed she brushed aside an officer with “too little force to have been intended to inflict any kind of injury.”

A Justice Department spokesperson said it will continue to seek the most serious available charges against those alleged to have put federal agents in harm’s way.

“We will not tolerate any violence directed toward our brave law enforcement officials who are working tirelessly to keep Americans safe,” said Natalie Baldassarre, a DOJ spokesperson.

The administration has deployed — or sought to deploy — troops to the four cities where AP examined the criminal cases: Washington, D.C, Los Angeles, Portland and Chicago. Trump and his administration have sought to justify the military deployments, in part, by painting immigration protesters as “antifa,” which the president has sought to designate as a “domestic terrorist organization.”

Short for “anti-fascists,” antifa is an umbrella term for far-left-leaning protesters who confront or resist white supremacists, sometimes clashing with law enforcement.

The AP’s review found a handful of references to “antifa” in court records in the cases it reviewed. The review found no case in which federal authorities officially accused a protester of being a “domestic terrorist” or part of an organized effort to attack federal agents.

Experts said they were surprised the Justice Department took five misdemeanor cases to trial, given that such trials eat up resources. They were further shocked that DOJ lost all those trials.

“When the DOJ tries to take a swing at someone, they should hit 99.9% of the time. And that’s not happening,” said Ronald Chapman II, a defense attorney who practices extensively in federal court.

The highest-profile loss involved Sean Charles Dunn, a Washington, D.C., man who tossed a Subway-style sandwich at a Border Patrol agent he had berated as a “fascist.” Dunn was acquitted Nov. 6 after a two-day trial.

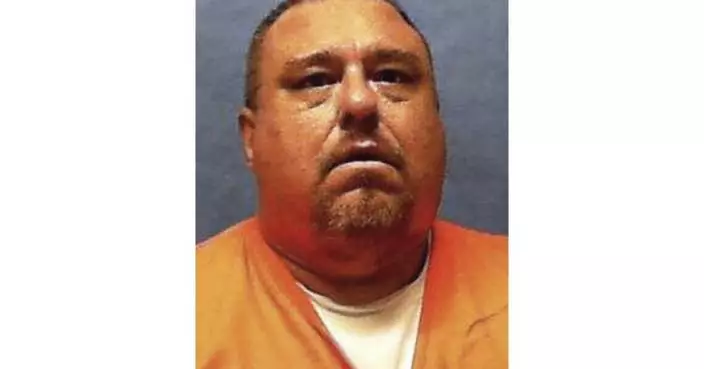

In Los Angeles, 32-year-old Katherine Carreño was acquitted on a misdemeanor assault charge stemming from an August protest outside a federal building.

Prosecutors had alleged she ignored an officer’s commands to move out of the way of a government vehicle and “raised her hand and brought it down in a slapping/chopping motion” onto the officer’s arm.

Social media video shown to jurors raised doubts about that narrative, showing an officer striding toward Carreño and pushing her back.

Prosecutors have secured felony indictments against 58 people, some of whom were initially charged with misdemeanors. They are accused of assaulting federal officers in several ways, including by hurling rocks and projectiles, punching or kicking them and shooting them with paintballs. None have yet to go to trial.

From the start of Trump’s second term through Nov. 24, the Department of Homeland Security says there have been 238 assaults on ICE personnel nationwide. The agency declined to provide its list or details about how it defines assaults.

“Rioters and other violent criminals have threatened our law enforcement officers, thrown rocks, bottles, and fireworks at them, slashed the tires of their vehicles, rammed them, ambushed them, and even shot at them,” said Department of Homeland Security Assistant Secretary Tricia McLaughlin.

Ding reported from Los Angeles, Fernando from Chicago, Rush from Portland, Oregon, and Foley from Iowa City, Iowa.

Contact the AP’s global investigative team at Investigative@ap.org or https://www.ap.org/tips/

FILE - California National Guard are positioned at the Federal Building on Tuesday, June 10, 2025, in downtown Los Angeles. (AP Photo/Eric Thayer, File)

FILE - Police and federal officers deploy gas canisters to disperse protesters near a U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement facility in Portland, Ore. on Oct. 5, 2025. (AP Photo/Ethan Swope, File)

Katherine Carreño stands for a portrait Saturday, Dec. 6, 2025, in Los Angeles. (AP Photo/Allison Dinner)

FILE - A protester is detained outside the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement facility on Sunday, Oct. 12, 2025, in Portland, Ore. (AP Photo/Jenny Kane, File)

Katherine Carreño stands for a portrait Saturday, Dec. 6, 2025, in Los Angeles. (AP Photo/Allison Dinner)

MBERA, Mauritania (AP) — The men move in rhythm, swaying in line and beating the ground with spindly tree branches as the sun sets over the barren and hostile Mauritanian desert. The crack of the wood against dry grass lands in unison, a technique perfected by more than a decade of fighting bushfires.

There is no fire today but the men — volunteer firefighters backed by the U.N. refugee agency — keep on training.

In this region of West Africa, bushfires are deadly. They can break out in the blink of an eye and last for days. The impoverished, vast territory is shared by Mauritanians and more than 250,000 refugees from neighboring Mali, who rely on the scarce vegetation to feed their livestock.

For the refugee firefighters, battling the blazes is a way of giving back to the community that took them in when they fled violence and instability at home in Mali.

Hantam Ag Ahmedou was 11 years old when his family left Mali in 2012 to settle in the Mbera refugee camp in Mauritania, 48 kilometers (30 miles) from the Malian border. Like most refugees and locals, his family are herders and once in Mbera, they saw how quickly bushfires spread and how devastating they can be.

“We said to ourselves: There is this amazing generosity of the host community. These people share with us everything they have," he told The Associated Press. "We needed to do something to lessen the burden."

His father started organizing volunteer firefighters, at the time around 200 refugees. The Mauritanians had been fighting bushfires for decades, Ag Ahmedou said, but the Malian refugees brought know-how that gave them an advantage.

“You cannot stop bushfires with water,” Ag Ahmedou said. “That’s impossible, fires sometimes break out a hundred kilometers from the nearest water source."

Instead they use tree branches, he said, to smother the fire.

"That’s the only way to do it,” he said.

Since 2018, the firefighters have been under the patronage of the UNHCR. The European Union finances their training and equipment, as well as the clearing of firebreak strips to stop the fires from spreading. The volunteers today count over 360 refugees who work with the region's authorities and firefighters.

When a bushfire breaks out and the alert comes in, the firefighters jump into their pickup trucks and drive out. Once at the site of a fire, a 20-member team spreads out and starts pounding the ground at the edge of the blaze with acacia branches — a rare tree that has a high resistance to heat.

Usually, three other teams stand by in case the first team needs replacing.

Ag Ahmedou started going out with the firefighters when he was 13, carrying water and food supplies for the men. He helped put out his first fire when he was 18, and has since beaten hundreds of blazes.

He knows how dangerous the task is but he doesn't let the fear control him.

“Someone has to do it,” he said. "If the fire is not stopped, it can penetrate the refugee camp and the villages, kill animals, kill humans, and devastate the economy of the whole region.”

About 90% of Mauritania is covered by the Sahara Desert. Climate change has accelerated desertification and increased the pressure on natural resources, especially water, experts say. The United Nations says tensions between locals and refugees over grazing areas is a key threat to peace.

Tayyar Sukru Cansizoglu, the UNHCR chief in Mauritania, said that with the effects of climate change, even Mauritanians in the area cannot find enough grazing land for their own cows and goats — so a “single bushfire” becomes life-threatening for everyone.

When the first refugees arrived in 2012, authorities cleared a large chunk of land for the Mbera camp, which today has more than 150,000 Malian refugees. Another 150,000 live in villages scattered across the vast territory, sometimes outnumbering the locals 10 to one.

Chejna Abdallah, the mayor of the border town of Fassala, said because of “high pressure on natural resources, especially access to water,” tensions are rising between the locals and the Malians.

Abderrahmane Maiga, a 52-year-old member of the “Mbera Fire Brigade,” as the firefighters call themselves, presses soil around a young seedling and carefully pours water at its base.

To make up for the vegetation losses, the firefighters have started setting up tree and plant nurseries across the desert — including acacias. This year, they also planted the first lemon and mango trees.

“It’s only right that we stand up to help people,” Maiga said.

He recalls one of the worst fires he faced in 2014, which dozens of men — both refugees and host community members — spent 48 hours battling. By the time it was over, some of the volunteers had collapsed from exhaustion.

Ag Ahmedou said he was aware of the tensions, especially as violence in Mali intensifies and going back is not an option for most of the refugees.

He said this was the life he was born into — a life in the desert, a life of food scarcity and "degraded land" — and that there is nowhere else for him to go. Fighting for survival is the only option.

“We cannot go to Europe and abandon our home," he said. "So we have to resist. We have to fight.”

For more on Africa and development: https://apnews.com/hub/africa-pulse

The Associated Press receives financial support for global health and development coverage in Africa from the Gates Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

Boys play football as the sun sets in the Mbera Refugee Camp, near Bassikounou, Hodh El Chargui Region, Mauritania, Saturday Nov. 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Caitlin Kelly)

Members of the NGO SOS desert plant trees in Mbera Refugee Camp, near Bassikounou, Hodh El Chargui Region, Mauritania, Saturday Nov. 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Caitlin Kelly)

Plants flower in the dry desert plains of the Sahel bloom in Mbera Refugee Camp, near Bassikounou, Hodh El Chargui Region, Mauritania, Saturday Nov. 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Caitlin Kelly)

Mbera fire brigade members from the NGO SOS desert demonstrate the brushing technique used to extinguish fires in Mbera Refugee Camp, near Bassikounou, Hodh El Chargui Region, Mauritania, Saturday Nov. 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Caitlin Kelly)

Mbera fire brigade members from the NGO SOS desert demonstrate the brushing technique used to extinguish fires in Mbera Refugee Camp, near Bassikounou, Hodh El Chargui Region, Mauritania, Saturday Nov. 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Caitlin Kelly)