AILSA CRAIG, Scotland (AP) — If you’re looking to strike gold — silver or bronze, too — look to Ailsa Craig.

This uninhabited isle 10 miles (16 kilometers) off the coast of southwest Scotland is the source of the super-dense granite used to make curling stones for the Winter Olympics.

Jim English, co-owner of Kays Curling, took a few seconds to evaluate a boulder during a recent visit. He assessed it for big cracks and large specks on the surface.

“It’s not just a case of landing a boat and then looking for granite. There’s a particular type of granite we’re looking for,” he said in the shadow of a 19th century lighthouse that is no longer manned. “We look for ones that have got really tight surface pattern.”

The common green granite comprising the body of the stone is found on one end, and the blue hone granite that forms the running surface is on the other side of the “ craggy ocean pyramid ” as poet John Keats described the island more than a century before the first Winter Games.

Kays, which has made all the curling stones for the Milan Cortina Winter Games, has a history with the Olympics dating back to the first winter edition — 1924 in Chamonix, France. The curling competition at those games was long thought to have been an exhibition event but eventually was confirmed as official. The company has continued to make stones for the games since curling returned as a medal sport in Nagano 1998.

Founded in 1851, Kays produces the stones from its shop in the town of Mauchline near Ayr.

"We can argue that it’s probably won every gold, silver and bronze medal since the sport became a medal sport back in 1998," said English.

Also called Kays Scotland, the company holds the only license to harvest granite from Ailsa Craig, which is owned by Lord David Thomas Kennedy, 9th Marquess of Ailsa.

Ailsa Craig, at about 1,110 feet (340 meters) high and 2 miles (3.2 kilometers) in circumference, is believed to have been formed from volcanic activity millions of years ago.

The Scottish Geology Trust wrote that the island is composed “ almost entirely of microgranite,” whose “essentially unflawed nature” make it ideal for curling stones.

Key elements of the sport are cold and collisions — teams push stones on ice toward a scoring zone and use brooms to influence the path. So, granite that cracks easily is of no use.

“The granite itself has got elasticity properties in it,” said Ricky English, operations manager at Kays and Jim's son. In a collision, energy is both absorbed and released, "so the stone doesn’t split,” he said.

The blue hone granite is essentially waterproof, making it perfect for the running surface.

“You can’t get this granite anywhere else in the world but Ailsa Craig,” Ricky English said of the blue hone.

The curling stones for the 2006 Turin Olympics were the first complete Ailsa Craig stones. Previously, Kays had also used some common green from a quarry in Wales.

Kays can go years between harvests. The common green “falls off naturally, so we just pick from the site," Ricky English said. Those selections weigh between 6 and 10 tons.

The blue hone requires dislodging from the cliff face. Engineers drill and insert a gas charge to break the rock along its natural cracks. Those boulders are under 2 tons, so higher quantities can mean fewer harvests.

Boulders are lifted into containers and ferried back to Girvan Harbour. Galloway Granite slices the boulders and cuts round “cheeses” from them, and sends them back to Kays.

The common green granite forms most of the stone, including the “striking band” around the middle. A hole is drilled through the center of the stone, which weighs on average 42 lbs (19 kg). The blue hone insert is glued in place, and the handle is attached. On a “double insert” — blue hone is attached to both sides, and the handle can screw in to either side.

A double insert costs 750 pounds ($990) — or 12,000 pounds ($15,860) for a set of 16. The single-insert stone is 704 pounds ($930).

Steps are taken on the island to protect a large colony of Gannets as well as some gray seals. Rat traps are set to be sure that boats from the mainland — the trip takes just over an hour — don't reintroduce the rodents to the island.

Scottish Curling traces the sport’s local roots back to 1540 in Paisley Abbey. Centuries later, curling is about to launch its first professional league, after the Milan Cortina Winter Olympics. The Rock League will feature events in the United States, Canada and Europe.

Kays produces 1,800 to 2,000 stones per year. Canada is its biggest market, while China, Japan and South Korea are increasing their orders.

“The market in Asia seems to be growing quite a bit,” Ricky English said. “The 2022 Olympics (in Beijing) has maybe just gave it that wee push over there.”

Kays has also sent stones to less-obvious curling spots like Qatar and Antarctica, where a travel company was using curling as part of a “luxury experience.”

Maguire reported from London.

AP Winter Olympics at https://apnews.com/hub/milan-cortina-2026-winter-olympics

A finished curling stone sits in a store room at Kays Curling stone factory in Mauchline, Scotland, Tuesday, Nov. 11, 2025. (AP Photo/Alastair Grant)

A craftsman checks a curling stone during a quality control phase at Kays Curling stone factory in Mauchline, Scotland, Tuesday, Nov. 11, 2025. (AP Photo/Alastair Grant,

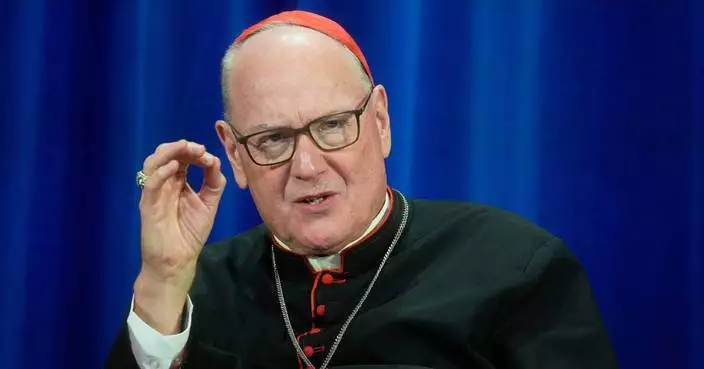

Jim English, Kays Curling Managing Director, looks at a boulder of granite on the island of Ailsa Craig, off the coast of Scotland, Monday, Nov. 10, 2025. (AP Photo/Alastair Grant)

A craftsman carries a Common Green granite block to be machined into a curling stone at Kays Curling stone factory in Mauchline, Scotland, Tuesday, Nov. 11, 2025. (AP Photo/Alastair Grant)

The island of Ailsa Craig, where the two types of granite, Common Green and Blue Hone, that are used to make curling stones is quarried from, is seen from the beach at Girvan, Scotland, Thursday, Nov. 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Alastair Grant)