LOS ANGELES (AP) — On the first anniversary of the most destructive wildfires in the L.A. area, the scant home construction projects stand out among the still mostly flattened landscapes.

Fewer than a dozen homes have been rebuilt in Los Angeles County since Jan. 7, 2025, when the Palisades and Eaton fires erupted, killing 31 people and destroying about 13,000 homes and other residential properties.

For those who had insurance, it’s often not enough to cover the costs of construction. Relief organizations are stepping in to help, but progress is slow.

Among the exceptions is Ted Koerner, whose Altadena home was reduced to ash and two chimneys. With his insurance payout tied up, the 67-year-old liquidated about 80% of his retirement holdings, secured contractors quickly, and moved decisively through the rebuilding process.

Shortly before Thanksgiving, Koerner was among the first to finish a rebuild in the aftermath of the fires, which were fueled by drought and hurricane-force winds.

But most do not have options like Koerner.

The streets of the coastal community of Pacific Palisades and Altadena, a community in the foothills of the San Gabriel Mountains, remain lined with dirt lots. In the seaside city of Malibu, foundations and concrete piles rising out of the sand are all that’s left of beachfront homes that once butted against crashing ocean waves.

Neighborhoods are pitch black at night, with few streetlamps replaced. Even many homes that survived are not inhabited as families struggle to clear them of the fire’s toxic contaminants.

Koerner was driven in part by fear that his beloved golden retriever, Daisy Mae, now 13 years old, might not live long enough to move into a new home, given the many months it can take to build even under the best circumstances.

He also did not have to wait for his insurance payout to start construction.

“That’s the only way we were going to get it done before all of a sudden my dog starts having labored breathing or something else happens,” Koerner said.

Once construction began, his home was completed in just over four months.

Daisy Mae is back lying in her favorite spot in the yard under a 175-year-old Heritage Oak. Koerner said he enjoys his morning coffee while watching her and it brings tears to his eyes.

“We made it,” he said.

About 900 homes are under construction, potentially on pace to be completed later this year.

Still, many homeowners are stuck as they figure out whether they can pay for the rebuilding process.

Scores of residents have left their communities for good. More than 600 properties where a single-family home was destroyed in the wildfires have been sold, according to real estate data tracker Cotality.

“We’re seeing huge gaps between the money insurance is paying out, to the extent we have insurance, and what it will actually cost to rebuild and/or remediate our homes,” said Joy Chen, executive director of the Eaton Fire Survivors Network, a group of 10,000 fire survivors mostly from Altadena.

By December, less than 20% of people who experienced total home loss had closed out their insurance claims, according to a survey by the nonprofit Department of Angels.

About one-third of insured respondents had policies with State Farm, the state’s largest private insurer, or the California FAIR plan, the insurer of last resort. They reported high rates of dissatisfaction with both, citing burdensome requirements, lowball estimates, and dealing with multiple adjusters.

In November, Los Angeles County opened a civil investigation into State Farm’s practices and potential violations of the state’s Unfair Competition law. Chen said the group has seen a flurry of substantial payouts since then.

Without answers from insurance, households can’t commit to rebuilding projects that can easily exceed $1 million.

“They’re worried about getting started and running out of money,” Chen said.

Jessica Rogers discovered only after the Palisades fire destroyed her home that her coverage had been canceled.

The mother of two’s fallback was a low-interest loan from the Small Business Administration, but the application process was grueling. After losing her job because of the fire and then having her identity stolen, her approval for $550,000 came through last month.

She is still weighing how she’ll cover the remaining costs and says she wonders: “Do I empty out my 401(k) and start counting every penny in a penny jar around the apartment?”

Rogers — now executive director of the Pacific Palisades Long Term Recovery Group — estimates there are hundreds like her in Pacific Palisades who are “stuck dealing with FEMA and SBA and figuring out if we could piecemeal something together to build our homes.”

Also struggling to return home are the community’s renters, condo owners, and mobile homeowners. Meanwhile, many are also dealing with their trauma.

“It’s not what people talk about, but it is incredibly apparent and very real,” said Rogers, who still finds herself crying at unexpected moments.

That so few homes have been rebuilt a year after the wildfires echoes the recovery pattern of a December 2021 blaze that erupted south of Boulder, Colorado, destroying more than 1,000 homes.

“At the one-year mark, many lots had been cleared of debris and many residents had applied for building permits, said Andrew Rumbach, co-lead of the Climate and Communities Program at Urban Institute. “Around the 18-month mark is when you start to see really significant progress in terms of going from handfuls to hundreds” of homes rebuilt.

Time will bring the scope of problems into focus.

“You’re going to start to see some real inequality start to emerge where certain neighborhoods, certain types of people, certain types of properties are just lagging way far behind, and that becomes the really important question in the second year of a recovery: Who’s doing well and who is really struggling and why?” Rumbach said.

That’s a key concern in Altadena, which for decades drew aspiring Black homeowners who otherwise faced redlining and other forms of racial discrimination when they sought to buy a home in other L.A.-area communities. In 2024, 81% of Black households in Altadena owned their homes, nearly twice the national Black homeownership rate.

But recent research by UCLA’s Latino Policy & Politics Institute found that, as of August, 7 in 10 Altadena homeowners whose property was severely damaged in last year’s wildfire had not begun taking steps to rebuild or sell their home. Among these, Black homeowners were 73% more likely than others to have taken no action.

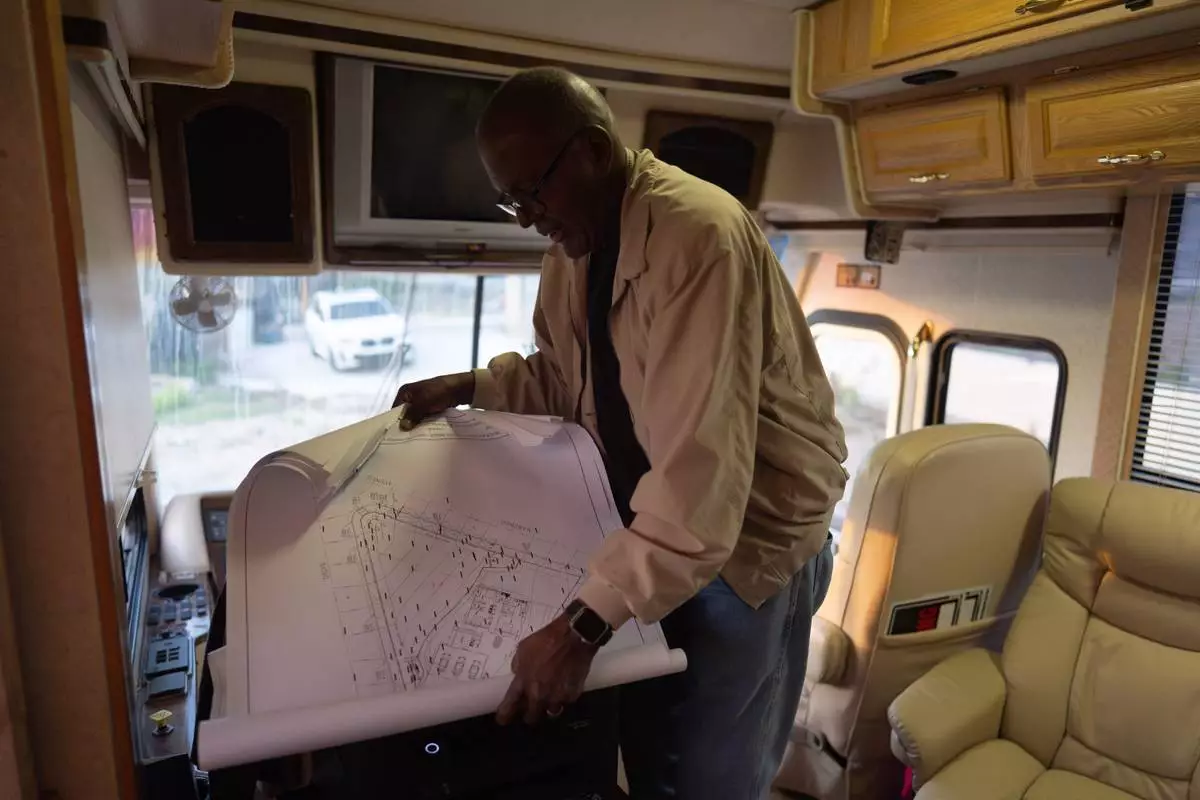

Al and Charlotte Bailey have been living in an RV parked on the empty lot where their home once stood.

The Baileys are paying for their rebuild with funds from their insurance payout and a loan. They’re also hoping to receive money from Southern California Edison. Several lawsuits claim its equipmentsparked the wildfire in Altadena.

“We had been here for 41 years and raised our family here, and in one night it was all gone,” said Al Bailey, 77. “We decided that, whatever it’s going to cost, this is our community."

A home being rebuilt is seen, Dec. 3, 2025, in Altadena, Calif., months after the Eaton Fire. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

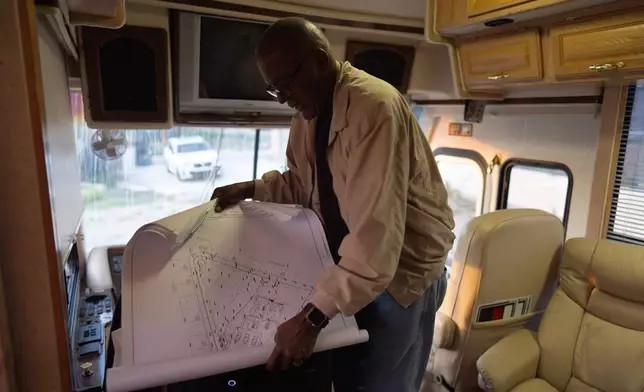

Ellaird Bailey, who lives in an RV on the property where his home was destroyed in the Eaton Fire, looks at building plans, Dec. 12, 2025, in Altadena, Calif. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Ellaird Bailey and his wife, Charlotte, who lost their home in the Eaton Fire, stand for a photo in front of their RV, which is parked on the property where their house once stood, Dec. 11, 2025, in Altadena, Calif. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

An aerial view shows houses being rebuilt on cleared lots months after the Palisades Fire, Dec. 5, 2025, in the Pacific Palisades neighborhood of Los Angeles. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

An aerial view shows houses being rebuilt on cleared lots months after the Palisades Fire, Dec. 5, 2025, in the Pacific Palisades neighborhood of Los Angeles. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)