NYON, Switzerland (AP) — Teams from former Iron Curtain countries are making their strongest challenge yet to win the Conference League, the competition designed to give them more chances to progress on and off the field.

The 24-team knockout phase has 10 from eastern Europe — the most in the continent's third-tier club competition since it was launched five years ago — and nine were in the knockout playoffs draw Friday.

Crystal Palace and Fiorentina face trips east in the playoffs after both preseason favorites found the opening phase tough, and failed to earn a top-eight placing last month that earned entry direct to the round of 16.

Palace is away in the first leg against Bosnian champion Zrinjski Mostar while Fiorentina — a two-time beaten finalist — will go to Poland to face Jagiellonia Bialystok.

Kosovo is represented in a knockout phase for the first time in its nine seasons playing in UEFA club competitions: Drita is at home first against Celje of Slovenia.

North Macedonia’s Shkendija was paired with Samsunspor of Turkey, and Armenian champion Noah will first host AZ Alkmaar of the Netherlands.

“It is exactly what the Conference League was designed for,” UEFA's director of competitions Giorgio Marchetti told The Associated Press. “We believe these three levels are needed."

First-leg games in the playoffs are played Feb. 19 and the returns are one week later.

Teams already in the round of 16 draw on Feb. 28 will include Strasbourg — whose coach Liam Rosenior left this month to join parent club Chelsea — Shakhtar Donetsk, Rayo Vallecano and Mainz.

A competition created by UEFA in 2021, in order to give lower-ranked clubs more chances to play into the second half of the season, will share a total prize fund of 285 million euros ($331 million).

“This competition is exactly for the teams like us. We love it,” Drita president Valon Murseli told the AP. His club is using several millions in UEFA prize money to build two soccer fields, one grass and one artificial. “For us, that’s a lot.”

Jagiellonia won the Polish league title in 2024 and is quickly trying to build a club tradition in Europe by learning from the host clubs it visits, like Fiorentina where it will play the second leg on Feb. 26.

“We are trying to be a big club. For everyone it’s a great opportunity,” Jagiellonia spokesman Emil Kaminski told the AP, highlighting the knowledge his team gained from seeing how opponents run their youth academies and commercial operations.

Soccer in the former Iron Curtain countries struggled to keep pace with the richer west after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, and the Bosman legal ruling in 1995 that upended the transfer market.

The European Court of Justice judgment led to players having freedom to move when their contracts expired without a transfer fee being paid to their club. It accelerated the flow of talent to richer clubs and cut revenue to those left behind.

No team from the east has reached a Champions League or European Cup final since Red Star Belgrade won the title in 1991.

The last team from the east to win any European title was Shakhtar’s Europa League victory in 2009.

The last finalist was Dnipro Dnipropetrovsk of Ukraine, who lost to Unai Emery’s Sevilla for the 2015 Europa League title. Four years later Dnipro folded in bankruptcy.

UEFA created the Conference League in part to help clubs who were overmatched in the Champions League and Europa League. Now, they can stay involved into February and beyond, and keep earning prize money.

Last season, Legia Warsaw earned almost 11 million euros ($12.8 million) for its Conference League run to the quarterfinals, while Petrocub Hincesti of Moldova received almost 4 million euros ($4.6 million) from the group stage.

The competition’s commitment to eastern Europe is shown by three of the four finals so far being hosted in Albania, the Czech Republic and Poland. The next final on May 27 is in Leipzig, a city that was in the former East Germany before the Berlin Wall fell.

The ideal path to progress in European soccer has been shown by Bodo/Glimt of Norway: A Conference League quarterfinal place in 2022, a Europa League semifinal last season and competing in its first Champions league main phase this season.

“We believe," Marchetti said, “there is much more hidden strength in Europe.”

AP soccer: https://apnews.com/hub/soccer

Fiorentina's Pietro Commuzzo celebrates after scoring during the Serie A soccer match between Fiorentina and Milan in Florence, Italy, Sunday, Jan. 11, 2026. (Massimo Paolone/LaPresse via AP)

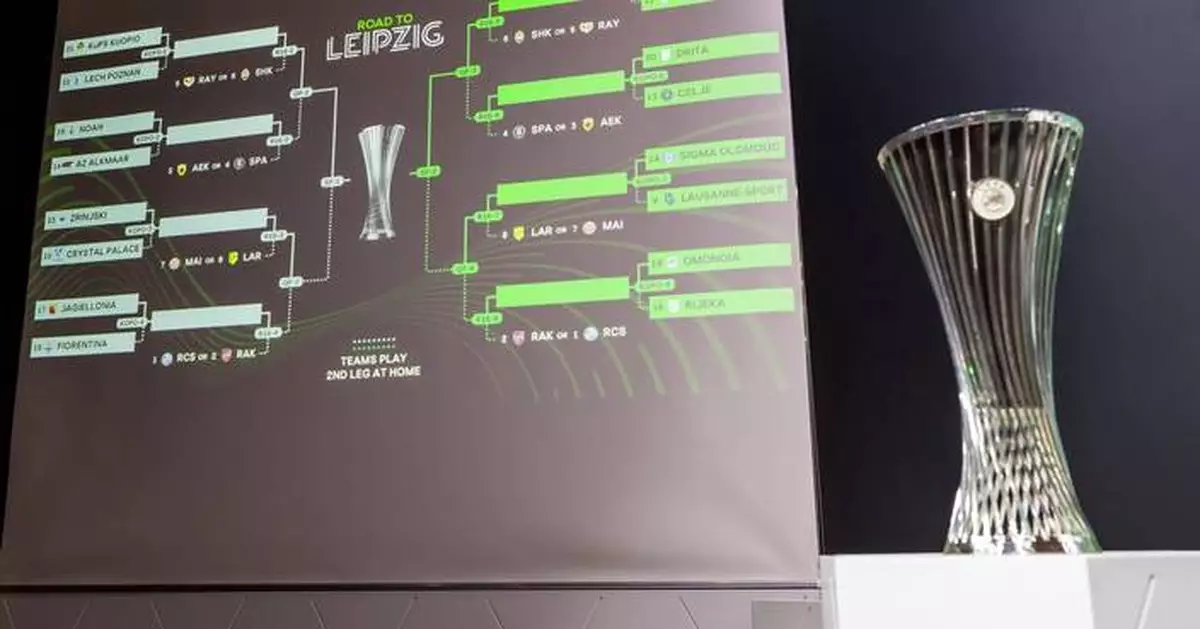

The group formations are shown on an electronic panel, after drawing the Conference League 2025/26 Knockout play-offs round draw, at the UEFA headquarters in Nyon, Switzerland, Friday, Jan. 16, 2025. (Martial Trezzini/Keystone via AP)

WASHINGTON (AP) — A plan to slash drug review times at the Food and Drug Administration is sparking deep concerns among agency staffers and outside experts, with some saying the poorly defined effort is taking key decisions away from career scientists and placing them in the hands of political leadership.

The initiative by FDA Commissioner Marty Makary promises ultra-fast reviews for drugs that align with “U.S. national priorities.” It’s at the center of Makary’s stated goal to “cut red tape” and “challenge assumptions” at the agency tasked with assuring the safety of food, medicines, medical devices and other consumer goods.

But FDA staffers say the push for faster approvals is contributing to a climate of anxiety, fear and confusion within the agency’s drug center, which has lost nearly 20% of its staff to recent layoffs, buyouts, retirements and resignations.

Concerns about the legality of the program have also contributed to the recent departure of several leaders of the FDA drug center, which is now being led by its fifth director in the past year.

FDA drug reviews have traditionally been handled by FDA career scientists who spend months analyzing data to determine whether drugs meet federal standards for safety and effectiveness.

But the effort to truncate certain drug approvals has become intertwined with White House efforts to secure pricing concessions for drugmakers, an unprecedented shift in the agency’s longstanding science-based approach that staffers fear could damage the FDA's reputation and endanger patients.

Health and Human Services spokesman Andrew Nixon said the voucher program prioritizes “gold standard scientific review” and aims to deliver “meaningful and effective treatments and cures.”

Here’s what to know:

Questions remain among top FDA officials over who has the appropriate legal authority to sign off on drugs cleared under the Commissioner’s National Priority Voucher program, according to several people with direct knowledge of the matter who spoke to The Associated Press on the condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to discuss confidential agency matters.

The FDA’s then-drug director, Dr. George Tidmarsh, declined to sign off on approvals under the pathway. Tidmarsh resigned from the agency in November over a lawsuit challenging his conduct on issues unrelated to the voucher program.

After his departure, Sara Brenner, the FDA’s principal deputy commissioner, was set to be the final decider on the approval decisions, but she also declined the role after looking further into the legal issues, according to the people. Currently the agency’s deputy chief medical officer, Dr. Mallika Mundkur, is taking on the responsibility.

Giving final approval to a drug carries significant legal weight, essentially certifying the medicine’s safety and effectiveness meet FDA standards. If unexpected side effects or other problems later emerge, both the agency and individual officials could be pulled into investigations or lawsuits.

Despite such concerns, the program remains popular at the White House, where pricing concessions announced by President Donald Trump, a Republican, have repeatedly been accompanied by FDA vouchers for drugmakers that agree to cut their prices.

For instance, when the White House announced that Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk would reduce prices on their popular obesity drugs, FDA staffers had to scramble to vet and announce new vouchers for both companies in time for the press conference, according to multiple people involved in the process.

That’s sparked widespread concern that FDA drug reviews have become malleable and open to political interference.

FDA approval decisions have nearly always been handled by agency scientists and their immediate supervisors, rather than political appointees and senior leaders.

But under the voucher program, approval comes through a committee vote by senior agency officials, according to multiple people familiar with the situation. Staff reviewers don’t get a vote.

Current and former staffers say the new approach flips FDA precedent on its head, minimizing the input of FDA scientists who have the greatest expertise and familiarity with the drug safety and effectiveness data.

Because of the ambiguity around the program’s workings, some drugmakers have had their own interpretation of the timeline for review — creating further confusion and stress among FDA staff.

Two people involved in the ongoing review of Eli Lilly’s anti-obesity pill said company executives initially told the FDA they expected the drug approved within two months.

The timeline alarmed FDA reviewers because it did not include the agency’s standard 60-day prefiling period, when staffers check the application to ensure it isn’t missing essential information.

But Lilly pushed for a quicker filing turnaround, demanding one week. Eventually the agency and the company agreed to a two-week period.

When reviewers raised concerns about some gaps in the application, one person involved in the process said, they were told by a senior FDA official that it was OK to overlook the regulations if the science is sound.

Former reviewers and outside experts say that approach is the opposite of how FDA reviews should work: It’s by following the regulations that staffers scientifically confirm the safety and effectiveness of drugs.

Nixon declined to comment on the specifics of Lilly’s review but said FDA reviewers can “adjust timelines as needed.”

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Department of Science Education and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

FILE - The Food and Drug Administration seal is seen at the Hubert Humphrey Building Auditorium in Washington, April 22, 2025. (AP Photo/Jose Luis Magana, File)