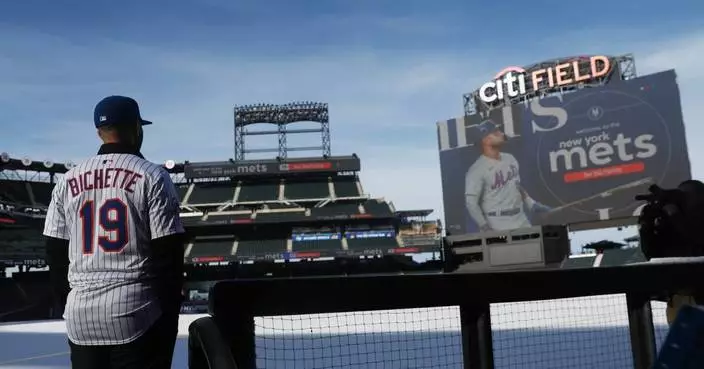

ZÁRATE, Argentina (AP) — The vast field of over 5,800 electric and hybrid vehicles gleamed on the cargo deck of the BYD Changzhou, an Chinese container vessel unloading Wednesday at a river port in eastern Argentina.

In other places, such a scene would not be noteworthy. Chinese automaker BYD has sped up its exports and undercut rivals the world over, alarming Washington, upsetting Western and Japanese auto giants and unnerving local industries across Southeast Asia, Africa and Latin America.

But the sight of so many new Chinese EVs gliding onto a muddy river bank in Buenos Aires province was unprecedented for Argentina, its crisis-stricken economy dominated for years by a left-wing populist movement that protected local industry with stiff tariffs and import restrictions.

“For decades people in Argentina had this vision that everything here must be manufactured here," said Claudio Damiano, a professor in the Institute of Transportation at Argentina’s National University of San Martin. “The boat has a symbolic value as the first step for BYD. Everyone’s wondering how far it will go.”

The shipment also came in stark contrast to the news in Brussels, where on Wednesday European Union lawmakers voted to delay ratification of a landmark free trade deal with the Mercosur group of South American countries, including Argentina, which promises to tear down trade barriers for European industrial imports and supercharge consumption of German EVs.

“For the Europeans, there's just no possibility of competing with the Chinese,” Damiano said.

Argentina became one of the region’s most closed economies under Kirchnerism — the movement formed by ex-President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner and her late husband, former President Néstor Kirchner, which championed the rights of the downtrodden, defaulted on sovereign debt and disdained global trade as a destructive force.

A chronically depreciating peso and sky-high taxes constrained consumer choice, compelling well-heeled Argentines to smuggle iPhones and Zara hauls into the country when returning from vacations abroad.

Fed up with cycles of economic crisis, Argentines vaulted radical libertarian President Javier Milei to power in 2023. He railed against Kirchnerism, vowed to destroy the state and praised U.S. President Donald Trump as an ideological soulmate.

For the last two years, Milei has has done the exact opposite of his most powerful ally in Washington.

While Trump has waged trade wars, Milei has flung open Argentina’s doors to imports, slashed trade barriers, unwound customs red tape and shored up the local currency to make foreign goods more affordable.

Last year Argentina logged a record 30% increase in imports compared to the year before — much of it in the form of $3 milk frothers and $10 dresses piling up on Argentines' doorsteps from Asian online retailers such as Temu and Shein.

Now Chinese automakers — once choked by 35% levies on imports — are seizing on a new measure to allow 50,000 electric and hybrid cars into the country this year tariff-free. The first shipment arrived Monday at Zárate Port after a 23-day voyage from Singapore.

Telling business and political leaders Wednesday at the World Economic Forum in Davos that that his drastic deregulation measures “allow us to have a more dynamically efficient economy,” Milei declared: “This is MAGA, ‘Make Argentina Great Again.

Milei and Trump share a contempt for perceived “wokeness,” a resentment of multilateral institutions like the United Nations, a denial of climate change and a zeal for massive budget cuts.

The ideological bond has paid dividends for Milei: Argentina is a rare place in the region where Trump has wielded the might of the U.S. to help an ally rather than enforce demands with military threats, as he has in Colombia and Mexico. Last year he offered Milei a $20 billion credit swap to boost his friend's chances in a crucial midterm election.

Yet at Davos, the leaders' differences were on display. Milei delivered his anti-interventionist, libertarian interpretation of MAGA shortly after Trump laid out his own vision for making America great: demanding control of Greenland and threatening allies with tariffs and other consequences if they don’t fall in line.

For all of Trump's support, China has perhaps benefited most from Milei's free-market drive.

Chinese imports to Argentina surged over 57% last year compared to the year before. Chinese investment poured into Argentina's energy and mining sectors.

“Argentina has rejoined the world," government spokesperson Javier Lanari said of Monday's Chinese car shipment. “Very soon, the Cuban-made vehicles left to us by Kirchnerism will be part of a sad and dark past.”

BYD and similar Chinese cars have already taken the streets of Latin America by storm, drawing controversy and backlash from Mexico City to Rio de Janeiro.

Now the brands are best positioned to reap the rewards of Milei’s zero-tariff quota for EVs, which applies only to cars under $16,000, experts say.

“Chinese manufacturers have the technology and the ability to meet the price limits set by the government," said Andrés Civetta, an economist specializing in the auto sector at the Argentine consulting firm Abeceb. “China has won the race."

Western car manufacturers in Argentina have raised alarms about unfair competition, and opposition lawmakers have criticized officials on the Chinese EV tariff exemption, with the comptroller general posting on social media, “Trump is right: China must be stopped.”

But Argentina is still far behind its neighbors in developing its EV industry, said Pablo Naya, the creator of Sero Electric, Argentina's only domestic electric car manufacturer.

The country's aging power grid is nowhere near ready for a wave of electric cars to strain it en masse, he said. And if something goes wrong with a Chinese EV on the road, there are currently no dealers' service centers able to undertake internal repairs.

“Honestly, we’re not worried,” Naya said.

But if or when Argentine infrastructure and consumer aspirations catch up to Chinese supply, it will be a different story.

“Then that would get complicated for us,” he said from the Sero Electric factory in the Buenos Aires suburb of Castelar. “We'd have a problem."

Ignacio Palacios works on a Sero Electric microcar at its factory in Castelar, Argentina, Wednesday, Jan. 21, 2026. (AP Photo/Victor R. Caivano)

Hybrid and electric vehicles shipped from China are unloaded from the BYD Changzhou car carrier docked at Terminal Zarate, in Argentina's Buenos Aires province, Tuesday, Jan. 20, 2026. (AP Photo/Victor R. Caivano)

BYD hybrid and electric vehicles shipped from China are parked at Terminal Zarate in Argentina's Buenos Aires province, Tuesday, Jan. 20, 2026. (AP Photo/Victor R. Caivano)

Pablo Naya, the owner of Sero Electric, poses next to one of the company's electric microcars at its factory in Castelar, Argentina, Wednesday, Jan. 21, 2026. (AP Photo/Victor R. Caivano)

The BYD Changzhou car carrier is docked at Terminal Zarate in the Buenos Aires province of Argentina, Tuesday, Jan. 20, 2026, where hybrid and electric vehicles shipped from China are parked next to the ship. (AP Photo/Victor R. Caivano)