TOKYO (AP) — Heavy snow battering northern Japan in the last two weeks has been blamed in 35 deaths nationwide so far, including people suffering sudden heart attacks or slipping while shoveling snow, government officials said Wednesday.

As of Wednesday, 15 prefectures have been affected, with the amount of snow piled up in the worst hit areas estimated to have reached 2 meters (6.5 feet).

Click to Gallery

People walk in a snow in Kanazawa, Ishikawa prefecture, Japan, on Jan. 23, 2026. (Kazushi Kurihara/Kyodo News via AP)

A person walks in a snow in Nagaoka, Niigata prefecture, Japan, on Jan. 22, 2026. (Chiaki Ueda/Kyodo News via AP)

People clear snow near houses in Aomori, northern Japan, Monday, Feb. 2, 2026. (Kyodo News via AP)

People clear snow near a building in Aomori, northern Japan, Monday, Feb. 2, 2026. (Kyodo News via AP)

The biggest number of snow-related fatalities, at 12 people, was reported in Niigata Prefecture, a rice-growing region in northern Japan, including a man in his 50s who was found collapsed on the roof of his home in Uonuma city on Jan. 21.

In Nagaoka city, a man in his 70s was spotted collapsed in front of his home and rushed to the hospital where he was pronounced dead. He is believed to have fallen from the roof while raking snow, according to the Niigata government.

Japan’s chief government spokesperson warned that, although the weather was getting warmer, more danger could lie ahead because snow would start melting, resulting in landslides and slippery surfaces.

“Please do pay close attention to your safety, wearing a helmet or using a lifeline rope, especially when working on clearing snow,” Chief Cabinet Secretary Minoru Kihara told reporters.

Various task forces were set up to respond to the heavy snow in Niigata and nearby regions, which began Jan. 20. Seven snow-related deaths have been reported in Akita Prefecture and five in Yamagata Prefecture.

Injuries nationwide numbered 393, including 126 serious injuries, 42 of them in Niigata. Fourteen homes were damaged, three in Niigata and eight in Aomori Prefecture.

The reason behind the heavy snowfall is unclear. But deaths and accidents related to heavy snow are not uncommon in Japan, with 68 deaths reported over the six winter months the previous year, according to the Fire and Disaster Management Agency.

More heavy snow is forecast for the coming weekend.

Yuri Kageyama contributed to this report. She is on Threads: https://www.threads.com/@yurikageyama

People walk in a snow in Kanazawa, Ishikawa prefecture, Japan, on Jan. 23, 2026. (Kazushi Kurihara/Kyodo News via AP)

A person walks in a snow in Nagaoka, Niigata prefecture, Japan, on Jan. 22, 2026. (Chiaki Ueda/Kyodo News via AP)

People clear snow near houses in Aomori, northern Japan, Monday, Feb. 2, 2026. (Kyodo News via AP)

People clear snow near a building in Aomori, northern Japan, Monday, Feb. 2, 2026. (Kyodo News via AP)

ROME (AP) — On a recent weeknight, long after the swarms of tourists had left Rome's Colosseum, a small group of people walked around outside the darkened amphitheater, pausing every so often to take in a new aspect of its history, art or architecture with every sense but sight.

Michela Marcato, 54, has been blind since birth. She and her partially sighted partner were touring the site amid a new effort by Italy to make its myriad artistic treasures more accessible to people with blindness or low vision and enhance how all visitors experience and perceive art.

As she listened to her tour guide, Marcato traced her fingers over a small souvenir model of the Colosseum. She felt the grooves of its archways and rugged rubble of its crumbled side. What she hadn't realized before holding it was the elliptical shape of building.

“Walking around it, I personally would never have realized it. I would never have understood it,” she said. “But with that little model in your hand, it’s obvious!”

Italy and its art-filled cities have no shortage of tourists, but they haven’t always been overly welcoming to visitors with disabilities. People who use wheelchairs often find elevators and doorways that are too narrow, stairs without ramps and uneven pavements.

But in 2021, as a condition of receiving European Union pandemic recovery funds, Italy accelerated its accessibility initiatives, dedicating more attention and resources to removing architectural barriers and making its tourist sites and sporting venues more accessible.

The ancient city of Pompeii recently installed a new system of signage to make the vast archaeological site more accessible to blind and disabled people. The project uses braille signs, QR-coded audio guides, tactile models and bas-relief replicas of artifacts that have been excavated over the years.

The city of Florence, for its part, has produced a guide on the accessibility options at the Uffizi Gallery and its other museums, with detailed information on routes and requirements — including the presence of companions — for sites such as the Boboli Gardens, which because of their historic structures are not fully accessible.

An inclusive tourism model doesn’t just honor the human rights of people with disabilities; it also makes economic sense. Nearly half of the world’s population aged over 60 has a disability, and disabled travelers tend to bring two or more companions, according to the World Tourism Organization.

Giorgio Guardi, a tour guide with the Radici Association, which has been leading tours of Rome for people with disabilities since 2015, said the aim of accessible tourism is to create an experience that is enjoyable for everyone involved, companions included.

That often means slowing down, touching what can be touched and experiencing artwork with different senses. The association often organizes walking tours at night, when there are fewer people out and less distracting ambient noise at famous landmarks.

But it isn’t always possible for blind people to touch artworks, so guides have to get creative.

Take Rome's central Campo dei Fiori piazza and its imposing statue of Giordano Bruno, the 16th-century philosopher burned at the stake during the Inquisition for alleged heresy.

The statue, which stands atop a large pedestal in the middle of the piazza, is too high for visitors to touch. On a recent nighttime tour of the piazza, Guardi encouraged his clients to instead assume Bruno’s position: Hunched over, wearing a heavy hooded cape and clasping a book with both hands.

As one of his clients assumed the position, Guardi draped the cape over him. Others in the group lined up to touch the Bruno impersonator to feel the contours of his drooped shoulders, heavy with the weight of the Inquisition. Visitors who were deaf were also part of the tour, aided by a sign-language interpreter who recounted Bruno’s tragic end.

Aldo and Daniela Grassini, both blind, were avid travelers and art collectors who grew increasingly frustrated that they weren't allowed to touch art when they visited museums around the world. In the early 1990s, they founded what subsequently become Italy's only publicly funded tactile museum, the Museo Omero in the Adriatic coastal city of Ancona, where all the art is meant to be handled.

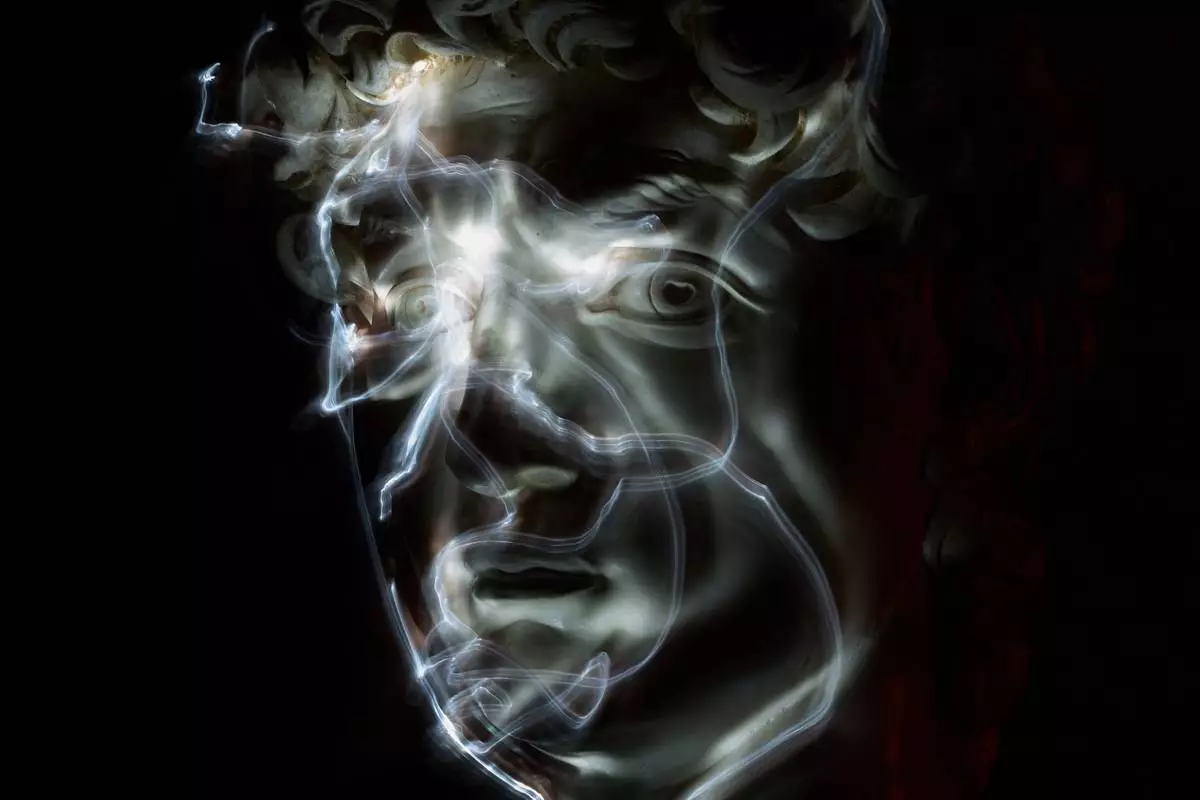

Named for the blind poet Homer, the museum features life-sized replicas of some of Italy’s most famous artworks, from ancient Roman and Greek statues to the head of Michelangelo’s David, as well as contemporary artworks.

“Touching something isn't like looking at it," said Aldo Grassini. "Not just because of the emotion it offers, but because of the type of knowledge that sensation provides.”

Sight, he said, is an “overbearing sense that tends to monopolize reality,” whereas touch offers a different dimension.

“We love with our eyes and with our hands. If we are in love with a person or an object that is particularly dear to us, is it enough to just look at it? No, we need to caress it, because caressing gives you a different emotion,” he said.

One of the artists whose work is on display at the museum is Felice Tagliaferri, who himself is blind.

At his studio on the outskirts of Cesena, Tagliaferri points to a marble bust he sculpted of his late friend Angela. Tagliaferri recalled that before Angela died of breast cancer, he lay down in bed with her, caressing her bald head.

“When she passed away, Angela remained in my hands, and I recreated this sculpture thinking of her,” he said.

Marcato, the woman who toured the Colosseum, and her partner Massimiliano Naccarato live in a smart apartment on Rome's east side whose living room is dominated by a huge painting of the sea.

Naccarato, who can see using his cellphone to enlarge images and with the help of special lights, purchased the painting to celebrate a professional award, and it has pride of place in their home.

Naccarato installed a special light behind the work so he can see it better. Marcato can’t see it at all, but she knows it’s there. And her own experience at the beach informs the way she enjoys the painting.

For her, the painting recalls her love of the sea, “for the noise it makes, for the thousand different sounds it produces, for the smell you breathe in, for the walks you can take in any season.”

It is a sensory way of appreciating art that has absolutely nothing to do with seeing it.

Nicole Winfield contributed.

Francesca Inglese, who is blind, touches a marble relief on the corner of a building during an inclusive art tour in downtown Rome, on Nov. 29, 2025. (AP Photo/Alessandra Tarantino)

Michela Marcato, left, who is blind, and her partially sighted partner Massimiliano Naccarato, stand in front of a painting representing the sea during an interview at their home in Rome, Monday, Jan. 12, 2026. (AP Photo/Alessandra Tarantino)

Aldo Grassini and Daniela Bottegoni, both blind, who founded in 1993 the Omero Tactile Museum, the first publicly funded tactile museum in Italy, pose for a portrait in their home in Ancona, Italy, Thursday, Jan. 15, 2026. (AP Photo/Alessandra Tarantino)

Stefania Terre, left, touches a reproduction of Michelangelo's sculpture La Pieta with Carmine Laezza, standing at right, during a tour for blind people with Monica Bernacchia, center, at the Omero Tactile Museum in Ancona, Italy, Thursday, Jan. 15, 2026. (AP Photo/Alessandra Tarantino)

Stefania Terre, who is blind, uses a small light on her fingers while touching a life-size reproduction of the head of Michelangelo's David as she poses for a long-exposure photograph at the Omero Tactile Museum in Ancona, Italy, Thursday, Jan. 15, 2026. (AP Photo/Alessandra Tarantino)