MINNEAPOLIS (AP) — Public health officials and community leaders say that even before federal immigration authorities launched a crackdown in Minneapolis, a crisis was brewing.

Measles vaccination rates among the state's large Somali community had plummeted, with the myth that the shot causes autism spreading. Not even four measles outbreaks since 2011 made a dent in the trend. But recently, immunization advocates noted small victories, including mobile clinics and a vaccine confidence task force.

Now, with the U.S. on the verge of losing its measles elimination status, those on the front lines of the battle against vaccine misinformation say much progress has been lost. Many residents fear leaving home at all, let alone seeking medical advice or visiting a doctor's office.

“People are worried about survival,” said nurse practitioner Munira Maalimisaq, CEO of the Inspire Change Clinic, near a Minneapolis neighborhood where many Somalis live. “Vaccines are the last thing on people’s minds. But it is a big issue.”

A discussion group for Somali mothers at Inspire Change has shifted online indefinitely. In community WhatsApp groups and other channels, parents have more pressing priorities: Who will care for kids when they can't go to school? How can we safely get groceries and prescriptions?

In 2006, 92% of Somali 2-year-olds were up-to-date on the measles vaccine, according to the Minnesota Department of Health. Today's rate is closer to 24%, according to state data. A 95% rate is needed to prevent outbreaks of measles, an extremely contagious disease.

Community vaccination efforts go through cycles, Maalimisaq said, with initiatives starting and stopping.

Imam Yusuf Abdulle said immigration enforcement has put everything on hold.

“People are stuck in their homes, cannot go to work,” he said. “It is madness. And the last thing to think about is talking about autism, talking about childhood vaccination. Adults cannot get out of the house, forget about kids.”

Estimated autism rates in Somali 4-year-olds are 3.5 times higher than those of white 4-year-olds in Minnesota, according to University of Minnesota data. Researchers say they don’t know why. And in this vacuum of scientific certainty, inaccurate beliefs thrive.

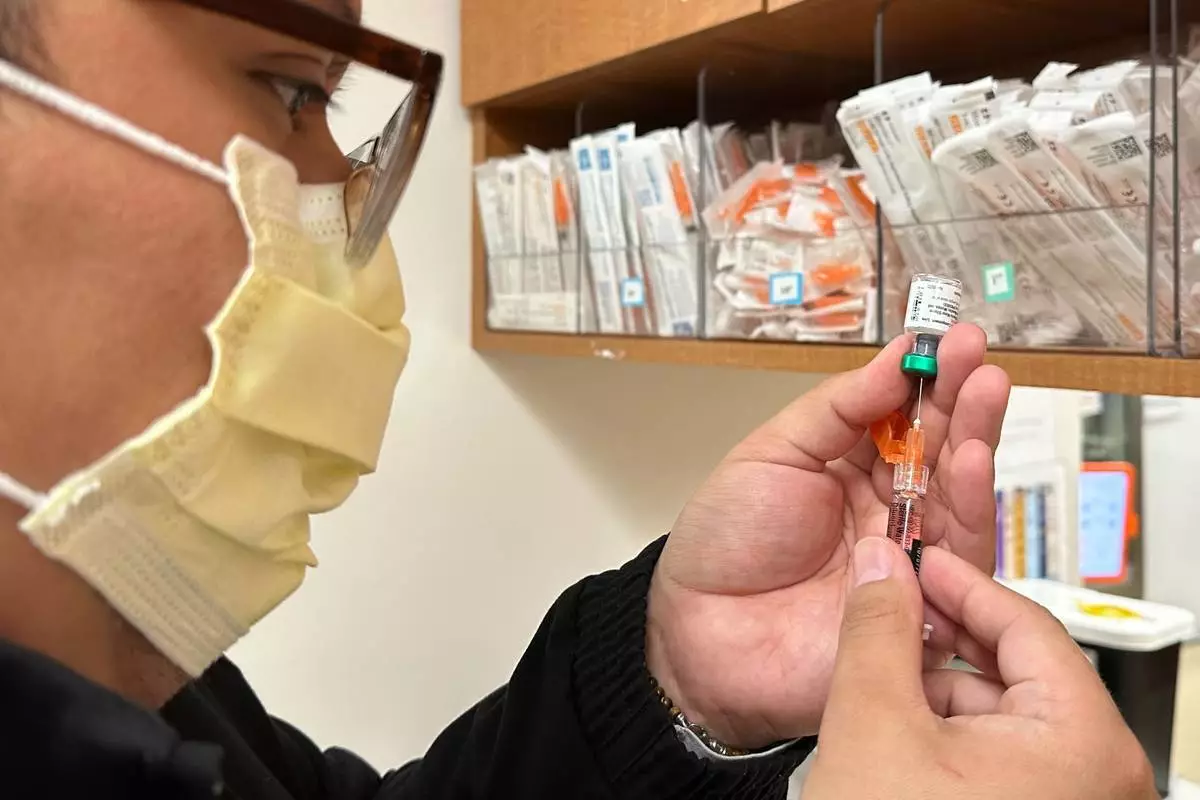

Many blame the measles, mumps and rubella shot — a single injection proven to safely protect against the three viruses, with the first dose recommended when children are 12 to 15 months old.

In November, at one of Maalimisaq’s last Motherhood Circle gatherings, Somali mothers and grandmothers volleyed questions at facilitators. Won’t a shot for three viruses overwhelm a baby? Why does autism seem more prevalent here than back home?

Vaccines are tested for safety, Maalimisaq and her panel explained. Delaying a shot is risky, they warned, because of what measles — which is seeing its highest spread in the country in more than three decades — can do.

Local health officials have long followed best practices: enlisting community members to champion vaccines, hosting mobile clinics and uplifting the work of Somali health providers like Maalimisaq.

But initiatives have been start-and-stop. Federal funding cuts affected efforts, and public health officials admit their outreach could be more consistent and comprehensive.

Most parents here vaccinate their children eventually. Many Somali families prefer to wait until a child is 5, despite a lack of evidence that doing so cuts autism rates. Measles is endemic in Somalia, where war and international aid cuts have crippled the medical system, and elsewhere in East Africa where residents here often travel.

“Measles is just a plane ride away, and measles is going to find the unvaccinated,” said Carly Edson, the state health department’s immunization outreach coordinator. “We are always at risk.”

About 84,000 Somalis live in the Twin Cities area, of 260,000 nationwide. The community is the country's largest, and most are U.S. citizens. Before the immigration crackdown, mosques and malls buzzed, with people gathering during evenings to sip chai or have henna drawn on their hands.

Now, many in the community want to lie low. People are afraid to seek routine medical care. Without those touchpoints, trust quickly erodes, Maalimisaq said.

Among the last cohort of Somali moms at the clinic, 83% had vaccinated their kids by the end of the 12-month program, she said. Some were making 10-second videos explaining why they vaccinated. But efforts have paused.

Parents here have long dealt with racism and isolation, though they’ve built a strong community. They want answers for the autism rates, but science has no simple answers for what causes the lifelong neurological condition, said Mahdi Warsama, the Somali Parents Autism Network's CEO.

Warsama said Trump's unproven claims last fall that taking Tylenol during pregnancy could cause autism sparked fears and questions here. The idea that the MMR shot should be split into three vaccines — one backed, with no scientific basis, by acting Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Director Jim O’Neill, though no standalone shots are available in the U.S. — has spread, too.

Warsama traces the issue back more than a decade, when discredited researcher Andrew Wakefield published his study — since retracted — claiming a link between autism and the MMR vaccine. Wakefield visited with Twin Cities Somalis in 2011.

“The misinformers will always fill the void,” Warsama said.

Parents want to be heard, not debated — that's why short doctor appointments don't work, said Fatuma Sharif-Mohamed, a Somali community health educator.

“That 15 minutes will not change the mind of a parent,” she said.

Some doctors are pushing beyond the exam room — work they describe as slow and taxing. Changing one family's mind can take multiple visits, even years.

Dr. Bryan Fate, leader of a Children's Minnesota vaccine confidence committee, said new strategies are underway, including social media videos from doctors and possibly a prenatal classes for expectant parents.

“I’m going to call you in five days,” Fate said he tells hesitant parents, “and there’ll be no changes to this speech.”

Overall, Minnesota’s kindergarten MMR vaccination rate has dropped more than 6 percentage points in the past five years, compared with a 2-point drop nationwide.

State data suggests the effort to catch kids up may be effective: While less than 1 in 4 Somali kids in Minnesota is vaccinated against measles by age 2, 86% get at least one dose by age 6 — just short of the statewide rate, 89%.

Doctors worry in particular about unprotected young children, for whom severe complications — pneumonia, brain swelling and blindness — are more common.

Imam Abdulle said when parents ask him about the vaccine, he tells his own story. He wasn’t opposed to it but decided to err on the side of waiting. His son was diagnosed with autism at age 3, Abdulle said, and later was vaccinated.

Correlation, he reminds parents, is not causation.

The community doesn't want to be painted as a source of disease, Abdulle said. But after outbreaks in 2011, 2017, 2022 and 2024, there’s also open acknowledgment that measles isn’t going away.

“Our kids are the ones who are getting sick,” Abdulle said. “Our community is suffering.”

Last year, Minnesota logged 26 measles cases. The state health department said the cases were across several different communities with pockets of unvaccinated people.

In Maalimisaq's Motherhood Circles, the most effective words often come not from doctors but fellow parents, such as Mirad Farah. Farah’s daughter was born premature. She worried the MMR shot would be too much and delayed vaccination. Her daughter still developed autism.

“So what did that tell me?” she asked the room. “It confirmed that autism is not from the MMR.”

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Department of Science Education and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

Licensed practical nurse Marco Flores prepares a patient's measles, mumps and rubella vaccine at Children's Minnesota on Nov. 20, 2025, in Minneapolis. (AP Photo/Devi Shastri)

Dr. Bryan Fate, second left, and family nurse practitioner and CEO of Inspire Change Clinic Munira Maalimisaq, middle, lead a community discussion on vaccine education at Inspire Change Clinic, Nov. 22, 2025, in Minneapolis. (AP Photo/Abbie Parr)

Panelist Mirad Farah, left, and Emory University Ph.D. candidate Ahmed Haji Said, middle, lead a community discussion on vaccine education at Inspire Change Clinic, Nov. 22, 2025, in Minneapolis. (AP Photo/Abbie Parr)

Fartun Wardere speaks during a community discussion on vaccine education at Inspire Change Clinic, Nov. 22, 2025, in Minneapolis. (AP Photo/Abbie Parr)

Dr. Bryan Fate, left, family nurse practitioner and CEO of Inspire Change Clinic Munira Maalimisaq, middle left, and panelist Mirad Farah, middle, lead a community discussion on vaccine education at Inspire Change Clinic, Nov. 22, 2025, in Minneapolis. (AP Photo/Abbie Parr)