CORTINA D'AMPEZZO, Italy (AP) — Sofia Goggia had a key role in securing the hosting rights of the Milan Cortina Olympics for Italy.

So it seemed fitting that the Italian downhiller lit the cauldron in Cortina to conclude Friday’s opening ceremony, while retired Olympic skiing champions Alberto Tomba and Deborah Compagnoni performed the honors simultaneously in Milan.

Click to Gallery

Italy's Sofia Goggia at the finish area during an alpine ski, women's downhill official training, at the 2026 Winter Olympics, in Cortina d'Ampezzo, Italy, Friday, Feb. 6, 2026. (AP Photo/Giovanni Auletta)

Italy's Sofia Goggia speeds down the course during an alpine ski, women's downhill official training, at the 2026 Winter Olympics, in Cortina d'Ampezzo, Italy, Friday, Feb. 6, 2026. (AP Photo/Marco Trovati)

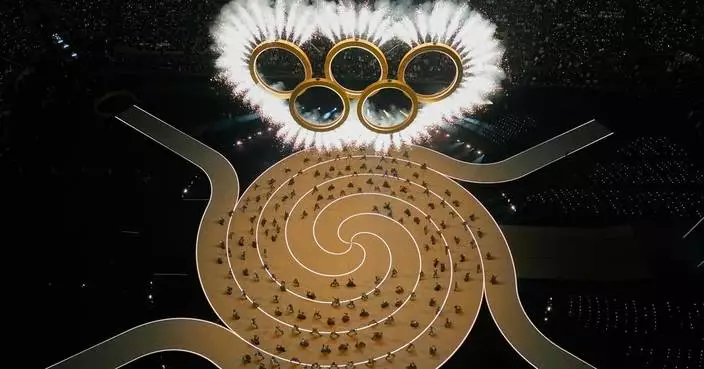

Final torchbearer Italian skier Sofia Goggia uses the torch of the Olympic flame to light the Olympic cauldron designed by Marco Balich during the Olympic opening ceremony at the 2026 Winter Olympics, in in Cortina d'Ampezzo, Italy, Friday, Feb. 6, 2026. (Stefano Rellandini/Pool Photo via AP)

Final torchbearer Italian skier Sofia Goggia holds the torch of the Olympic flame to light the Olympic cauldron designed by Marco Balich during the Olympic opening ceremony at the 2026 Winter Olympics, in in Cortina d'Ampezzo, Italy, Friday, Feb. 6, 2026. (Stefano Rellandini/Pool Photo via AP)

In 2019, Goggia and snowboarder Michela Moioli made a joint speech and dabbed in unison before nearly 100 members of the International Olympic Committee at the voting session for the 2026 Games. Their presentation was later considered vital for Milan Cortina’s successful bid — winning over voters with their positive energy to overcome a rival candidacy from Sweden.

Goggia won gold in the downhill at the 2018 Olympics and took silver four years later in Beijing weeks after crashing in Cortina.

She’ll race for more medals in the women’s downhill on Sunday in Cortina.

Goggia has had a series of highs and lows in Cortina. She’s won four World Cup downhills on the mountain but missed the 2021 world championships at the Alpine resort because of injury.

It was a big night for Italian Alpine skiers, with defending overall World Cup champion Federica Brignone one of the host country’s flag bearers in Cortina. Olympic curling champion Amos Mosaner, Italy’s other flag bearer in Cortina, held Brignone on his shoulders when the Azzurri paraded through the town center.

“I’m heavy,” Brignone said, “so I wasn’t sure he could carry me.”

AP Olympics: https://apnews.com/hub/milan-cortina-2026-winter-olympics

Italy's Sofia Goggia at the finish area during an alpine ski, women's downhill official training, at the 2026 Winter Olympics, in Cortina d'Ampezzo, Italy, Friday, Feb. 6, 2026. (AP Photo/Giovanni Auletta)

Italy's Sofia Goggia speeds down the course during an alpine ski, women's downhill official training, at the 2026 Winter Olympics, in Cortina d'Ampezzo, Italy, Friday, Feb. 6, 2026. (AP Photo/Marco Trovati)

Final torchbearer Italian skier Sofia Goggia uses the torch of the Olympic flame to light the Olympic cauldron designed by Marco Balich during the Olympic opening ceremony at the 2026 Winter Olympics, in in Cortina d'Ampezzo, Italy, Friday, Feb. 6, 2026. (Stefano Rellandini/Pool Photo via AP)

Final torchbearer Italian skier Sofia Goggia holds the torch of the Olympic flame to light the Olympic cauldron designed by Marco Balich during the Olympic opening ceremony at the 2026 Winter Olympics, in in Cortina d'Ampezzo, Italy, Friday, Feb. 6, 2026. (Stefano Rellandini/Pool Photo via AP)

PORTLAND, Ore. (AP) — Lawyers for conservation groups, Native American tribes, and the states of Oregon and Washington returned to court Friday to seek changes to dam operations on the Snake and Columbia Rivers, following the collapse of a landmark agreement with the federal government to help recover critically imperiled salmon runs.

Last year President Donald Trump torpedoed the 2023 deal, in which the Biden administration had promised to spend $1 billion over a decade to help restore salmon while also boosting tribal clean energy projects. The White House called it “radical environmentalism” that could have resulted in the breaching of four controversial dams on the Snake River.

Referring to the decades-long litigation, U.S. District Judge Michael Simon in Portland said it was “deja vu all over again” as he opened the hearing in a packed courtroom.

The plaintiffs argue that the way the government operates the dams violates the Endangered Species Act, and judges have repeatedly ordered changes to help the fish over the years. They're asking the court to order changes at eight large hydropower dams, including lowering reservoir water levels, which can help fish travel through them faster, and increasing spill, which can help juvenile fish pass over dams instead of through turbines.

“We are looking at fish that are on the cusp of extinction,” Amanda Goodin, an attorney with Earthjustice, a nonprofit law firm representing conservation, clean energy and fishing groups in the litigation, said during the hearing. “This is not a situation that can wait.”

In court filings, the federal government called the request a “sweeping scheme to wrest control” of the dams that would compromise the ability to operate them safely and efficiently. Any such court order could also raise rates for utility customers, the government said.

The lengthy legal battle was revived after Trump pulled the U.S. out of the Resilient Columbia Basin Agreement last June. The pact with Washington, Oregon and four Native American tribes had allowed for a pause in the litigation.

The plaintiffs, which include the state of Oregon and a coalition of conservation and fishing groups such as the National Wildlife Federation, filed the motion for a preliminary injunction, with Washington state, the Nez Perce Tribe and Yakama Nation supporting it as “friends of the court.” The parties have described salmon as central to Northwest tribal life.

The Columbia River Basin, spanning an area roughly the size of Texas, was once the world’s greatest salmon-producing river system, with at least 16 stocks of salmon and steelhead. Today, four are extinct and seven are endangered or threatened. Another iconic but endangered Northwest species, a population of killer whales, also depend on the salmon.

The construction of the first dams on the Columbia River, including the Grand Coulee and Bonneville in the 1930s, provided jobs during the Great Depression as well as hydropower and navigation. They made the town of Lewiston, Idaho, the most inland seaport on the West Coast, and many farmers continue to rely on barges to ship their crops.

Opponents of the proposed dam changes include the Inland Ports and Navigation Group, which said in a statement last year that increasing spill “can disproportionately hurt navigation, resulting in disruptions in the flow of commerce that has a highly destructive impact on our communities and economy.”

However, the dams are also a main culprit behind the decline of salmon, which regional tribes consider part of their cultural and spiritual identity.

Speaking before the hearing, Jeremy Takala of the Yakama Nation Tribal Council said “extinction is not an option.”

“This is very personal to me. It's very intimate,” he said, describing how his grandfather took him to go fishing. “Every season of lower survival means closed subsistence fisheries, loss of ceremonies and fewer elders able to pass on fishing traditions to the next generation.”

The dams for which changes are being sought are the Ice Harbor, Lower Monumental, Little Goose and Lower Granite on the Snake River, and the Bonneville, The Dalles, John Day and McNary on the Columbia.

FILE - Water spills over the Bonneville Dam on the Columbia River, which runs along the Washington and Oregon state line, June 21, 2022. (AP Photo/Jessie Wardarski, File)

FILE - Water moves through a spillway of the Lower Granite Dam on the Snake River near Almota, Wash., April 11, 2018. (AP Photo/Nicholas K. Geranios, File)

FILE - This photo shows the Ice Harbor dam on the Snake River in Pasco, Wash, Oct. 24, 2006. (AP Photo/Jackie Johnston, File)