SAN FRANCISCO (AP) — Connor Haught has been juggling virtual work meetings and arts and crafts projects for his two daughters as his family tries to navigate a teachers strike in San Francisco with no end date in sight.

Haught’s job in the construction industry allows him to work from home but, like many parents in the city, he and his wife were scrambling to plan activities for their children amid the uncertainty of a strike that has left nearly 50,000 students out of the classroom.

Click to Gallery

English and Physical Education teacher Alison White leads a chant as teachers and San Francisco Unified School District staff join a city-wide protest to demand a fair contract at Mission High School, Monday, Feb. 9, 2026, in San Francisco. (Brontë Wittpenn/San Francisco Chronicle via AP)

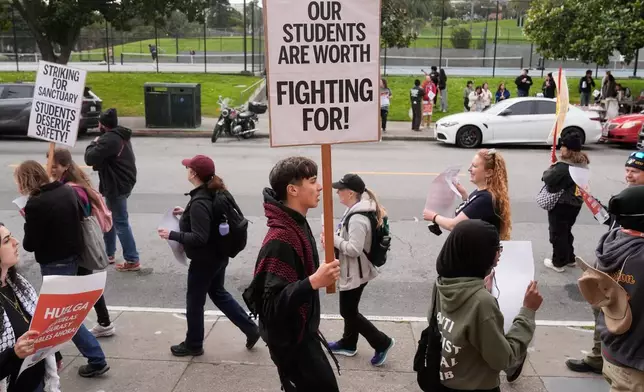

Teachers, students and supporters picket outside of Mission High School in San Francisco, Monday, Feb. 9, 2026. (AP Photo/Jeff Chiu)

Bret Harte Elementary Stacey Gonzalez TK teacher reads a United Educators of San Francisco newspaper as Bret Harte Elementary School teachers and Untied Educators of San Francisco members strike outside of Bret Harte Elementary School in San Francisco, Calif., Tuesday, Feb. 10, 2026. (Jessica Christian/San Francisco Chronicle via AP)

Bret Harte Elementary kindergarten to second grade teacher Kalina Francois pushes her daughter Inayah, 1, in a stroller while joining Bret Harte Elementary School teachers and Untied Educators of San Francisco members in a strike outside of Bret Harte Elementary School in San Francisco, Calif., Tuesday, Feb. 10, 2026. (Jessica Christian/San Francisco Chronicle via AP)

Teachers, students and supporters picket outside of Mission High School in San Francisco, Monday, Feb. 9, 2026. (AP Photo/Jeff Chiu)

“The big concern for parents is really the timeline of it all and trying to prepare for how long this could go on,” Haught said.

The San Francisco Unified School District’s 120 schools were set to remain closed for a third day Wednesday, after about 6,000 public schoolteachers went on strike over higher wages, health benefits, and more resources for students with special needs.

Some parents are taking advantage of after-school programs offering full-day programming during the strike, while others are relying on relatives and each other for help with child care.

Haught said he and his wife, who works evenings at a restaurant, planned to have their 8- and 9-year-old daughters at home the first week of the strike. They hope to organize play dates and local excursions with other families. They have not yet figured out what they will do if the strike goes on a second week.

“We didn’t try to jump on all the camps and things right away because they can be pricey, and we may be a little more fortunate with our schedule than some of the other people that are being impacted,” Haught said.

The United Educators of San Francisco and the district have been negotiating for nearly a year, with teachers demanding fully funded family health care, salary raises and the filling of vacant positions impacting special education and services.

Teachers on the picket lines said they know the strike is hard on students but that they walked out to offer children stability in the future.

“This is for the betterment of our students. We believe our students deserve to learn safely in schools and that means having fully staffed schools. That means retaining teachers by offering them competitive wage packages and health care and it means to fully fund all of the programs we know the student need the most,” said Lily Perales, a history teacher at Mission High School.

Superintendent Maria Su said Tuesday there was some progress in the negotiations Monday, including support for homeless families, AI training for teachers and establishing best practices for the use of AI tools.

But the two sides have yet to agree on a wage increase and family health benefits. The union initially asked for a 9% raise over two years, which they said could help offset the cost of living in San Francisco, one of the most expensive cities in the country. The district, which faces a $100 million deficit and is under state oversight because of a long-standing financial crisis, rejected the idea. Officials countered with a 6% wage increase paid over three years.

On Tuesday, Sonia Sanabria took her 5-year-old daughter and 11-year-old nephew to a church in the Mission District neighborhood that offered free lunch to children out of school.

Sanabria, who works as a cook at a restaurant, said she stayed home from work to take care of the children.

“If the strike continues, I’ll have to ask my job for a leave of absence, but it will affect me because if I don’t work, I don’t earn,” Sanabria said.

She said her elderly mother helps with school drop off and pick up but leaving the children with her all day is not an option. Sanabria said she has given them reading and writing assignments and worked with them on math problems. Sanabria said she is making plans for the children day-by-day and expressed support for the striking teachers.

“They are asking for better wages and better health insurance, and I think they deserve that because they teach our children, they take care of them and are helping them to have a better future,” she said, adding, “I just hope they reach agreement soon.”

English and Physical Education teacher Alison White leads a chant as teachers and San Francisco Unified School District staff join a city-wide protest to demand a fair contract at Mission High School, Monday, Feb. 9, 2026, in San Francisco. (Brontë Wittpenn/San Francisco Chronicle via AP)

Teachers, students and supporters picket outside of Mission High School in San Francisco, Monday, Feb. 9, 2026. (AP Photo/Jeff Chiu)

Bret Harte Elementary Stacey Gonzalez TK teacher reads a United Educators of San Francisco newspaper as Bret Harte Elementary School teachers and Untied Educators of San Francisco members strike outside of Bret Harte Elementary School in San Francisco, Calif., Tuesday, Feb. 10, 2026. (Jessica Christian/San Francisco Chronicle via AP)

Bret Harte Elementary kindergarten to second grade teacher Kalina Francois pushes her daughter Inayah, 1, in a stroller while joining Bret Harte Elementary School teachers and Untied Educators of San Francisco members in a strike outside of Bret Harte Elementary School in San Francisco, Calif., Tuesday, Feb. 10, 2026. (Jessica Christian/San Francisco Chronicle via AP)

Teachers, students and supporters picket outside of Mission High School in San Francisco, Monday, Feb. 9, 2026. (AP Photo/Jeff Chiu)

LOS ANGELES (AP) — How many Democrats are too many?

In the race for California governor, so many Democratic candidates have crowded into the contest that party insiders have become fearful of a historic calamity in the making. It’s become mathematically possible that Democrats divide their vote so much that two Republicans advance from the June primary to the general election.

“It’s the parlor game in Sacramento right now — could this happen?” Democratic consultant Paul Mitchell said.

The uncertainty in the outcome stems from the state’s unpredictable “ top two ” primary system. All candidates appear on a single ballot but only the two top finishers advance to the November general election, regardless of party. It's the first time since voters approved that system more than a decade ago that there's been a governor's race with no clear frontrunner, helping feed a “Why not me?” mentality among the large number of Democrats flooding into the contest.

“There’s a very real chance there could be only Republicans on November’s ballot,” the campaign of former U.S. Rep. Katie Porter, a Democratic gubernatorial candidate, warned in a recent fundraising pitch.

Though it remains a distant longshot, it's hard to understate the political shock that would come with two Republicans perched atop California's midterm ballot. The state is known as a Democratic fortress, and a GOP candidate hasn’t won a statewide election in two decades. It would also have implications for races down the ballot, including congressional battlegrounds that could determine control of the U.S. House.

Why so many candidates? The governor's chair in California has always had magnetic allure — it’s one of the most powerful political platforms in the nation. The state — by itself — is ranked as the world’s fourth-largest economy. It’s the nation’s top agricultural producer and is home to Silicon Valley and Hollywood. The state budget tallies nearly $350 billion in annual spending, an amount roughly equal to the market value of Netflix.

With Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom barred by law from seeking a third term, it's the most wide-open contest for governor in a generation.

Dozens of people have filed paperwork to run, from a college student to a billionaire. Among them are at least nine Democrats with the name recognition and fundraising machinery to seriously compete.

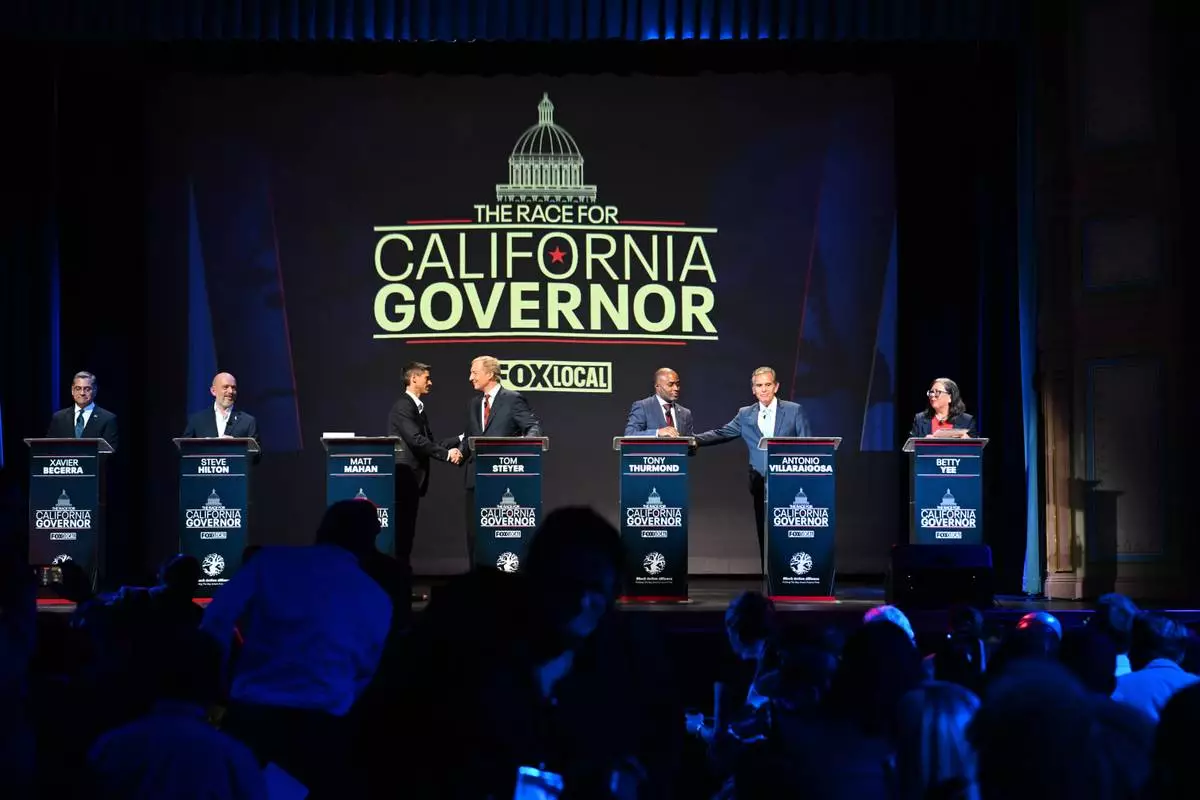

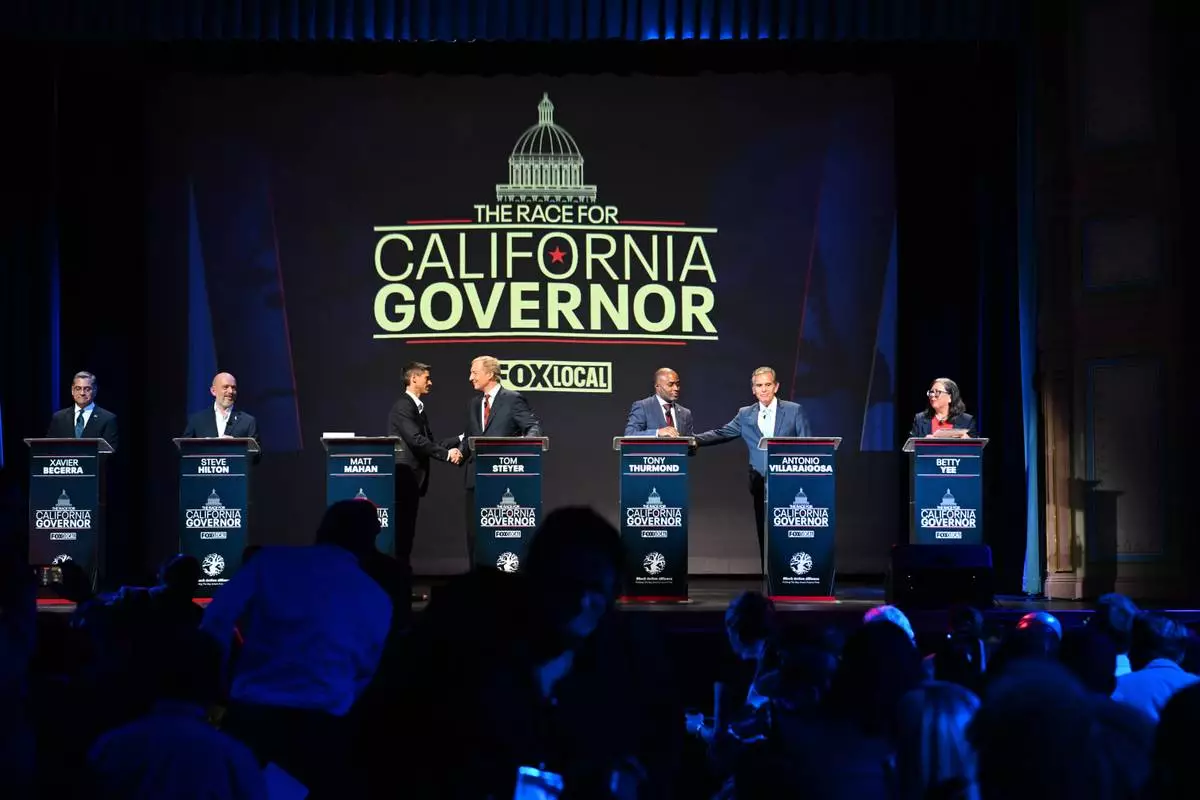

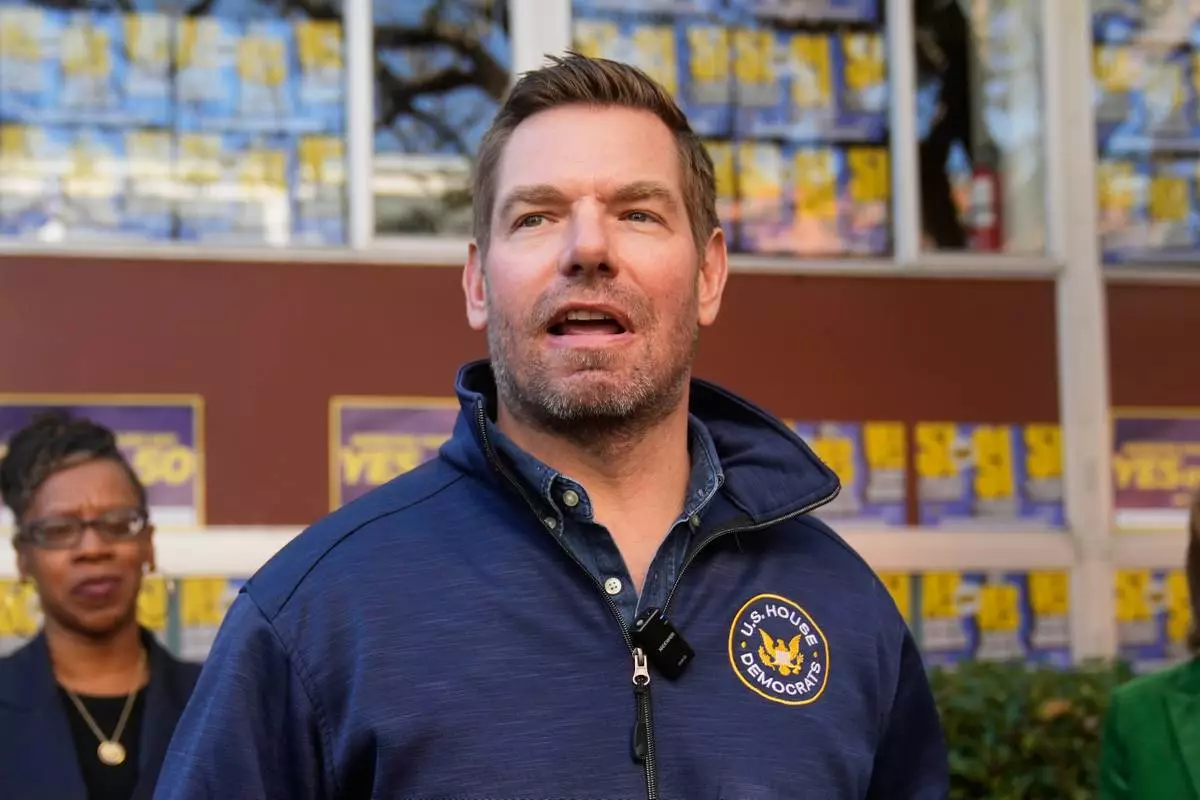

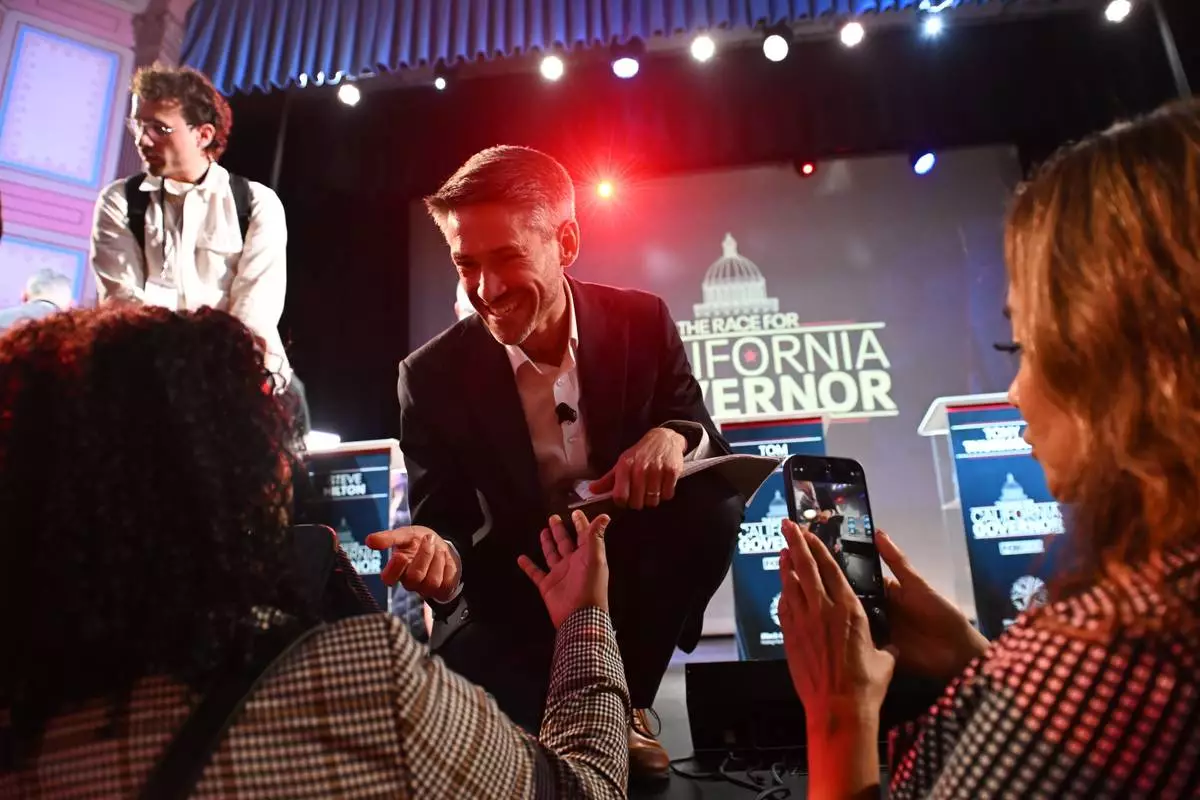

That list includes current and former members of Congress — Porter, Rep. Eric Swalwell and Xavier Becerra, who later served as the Biden administration’s top health official; former state controller Betty Yee and schools superintendent Tony Thurmond; billionaire Tom Steyer; San Jose Mayor Matt Mahan; former Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa; and Ian Calderon, a former majority leader in the state Assembly.

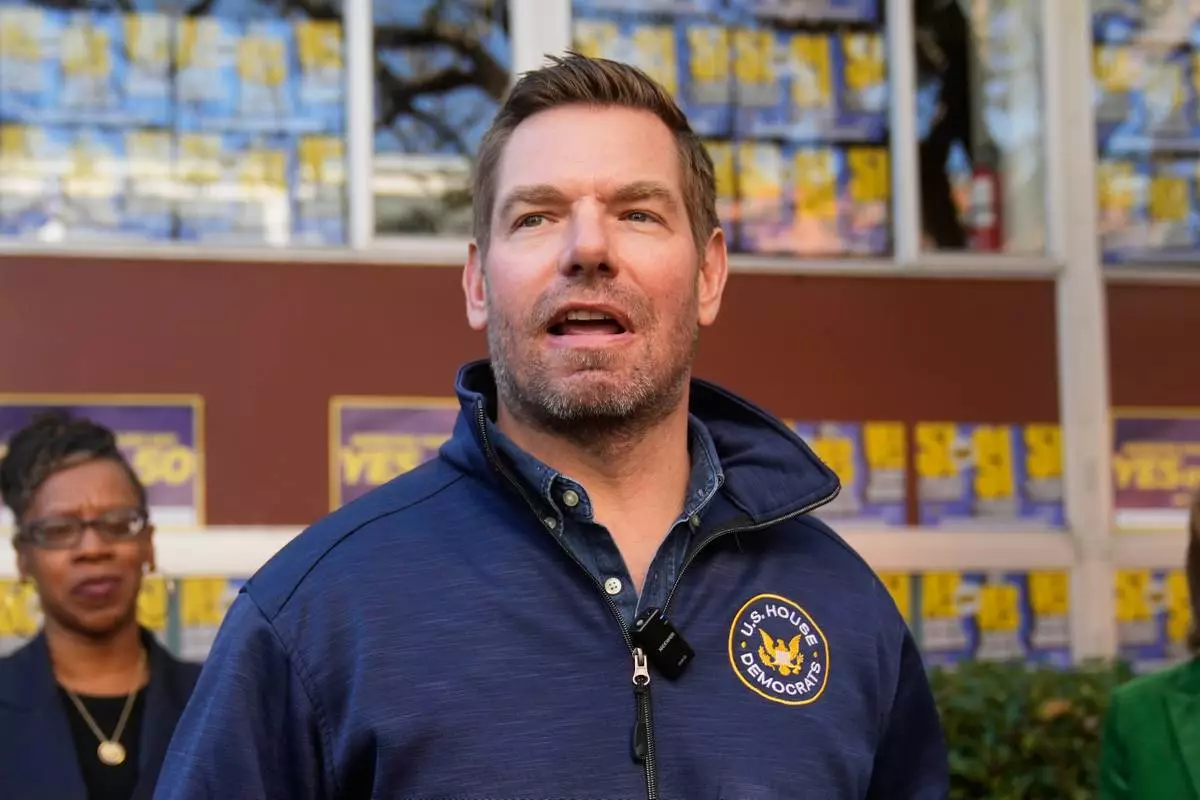

With the Democrats occupying much of the same ideological turf, candidates are highlighting other markers to break away from the pack. Swalwell, for example, has campaigned partly on his role as a House manager of Trump’s 2021 impeachment trial. Mahan, the newest candidate in the race, has been a frequent critic of Newsom on crime and homelessness. Steyer is among Mahan’s top critics, saying he’s too aligned with tech interests.

Some Democrats hope to see the field narrow on its own.

It would be best for “the lower-tiered people to drop out,” said Democratic strategist Drexel Heard II, former executive director of the Los Angeles County Democratic Party. “You are looking at people who are never going to break through.”

Mitchell said he used available polling data to run a series of simulations to assess the likelihood of a twin GOP breakthrough and found it was possible, though with long odds. The leading GOP candidates are Riverside County Sheriff Chad Bianco and conservative commentator Steve Hilton, both supporters of President Donald Trump.

California is one of the most solidly Democratic states in the country. Registered Democrats outnumber Republicans by nearly 2-to-1 statewide, Democrats have held every statewide office since 2010 and Republicans have been reduced to powerless spectators in the Legislature.

In a primary, the Democrats are expected to divide roughly 60% of the vote, Republicans, 40%. The math gets challenging for Democrats if the party has a long list of credible candidates in the race, cutting up their share of the vote.

“It’s a small probability but one that would be a massive, massive deal,” Mitchell said. The quandary for Democrats: “There isn’t somebody who is going to come in and tell these lower-tier candidates they can’t run.”

Republicans, for their part, are also concerned about the tricky math. Hilton has been calling on Bianco to drop out in hopes that Republicans would consolidate to push one candidate into the November election.

“We cannot risk splitting the Republican vote and letting the Democrats in,” Hilton said in a recent debate.

The race is displaying some similarity with the rapidly developing 2028 Democratic contest for president, where a large field is assembling to contend for an open seat. Democrats are still regrouping from the thrashing the national party suffered in 2024 and candidates in both races are testing messages they hope will galvanize voters in the midterms and beyond.

With Republicans in charge of Congress and the White House and many Americans pessimistic about the future, the abundance of candidates is a sign of both energy and frustration within the party, said Democratic consultant Antjuan Seawright.

The common denominator between the races: “We have to learn how to focus on the game of expansion and strengthening our coalition,” Seawright said.

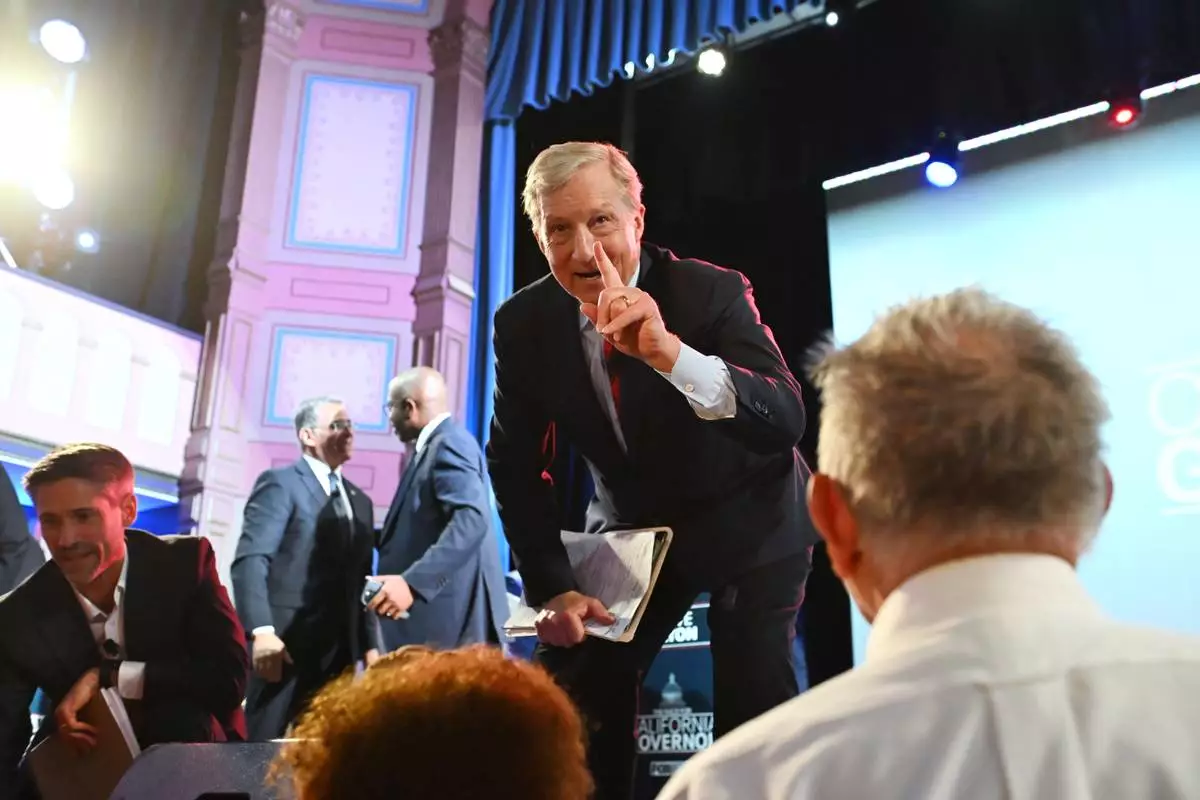

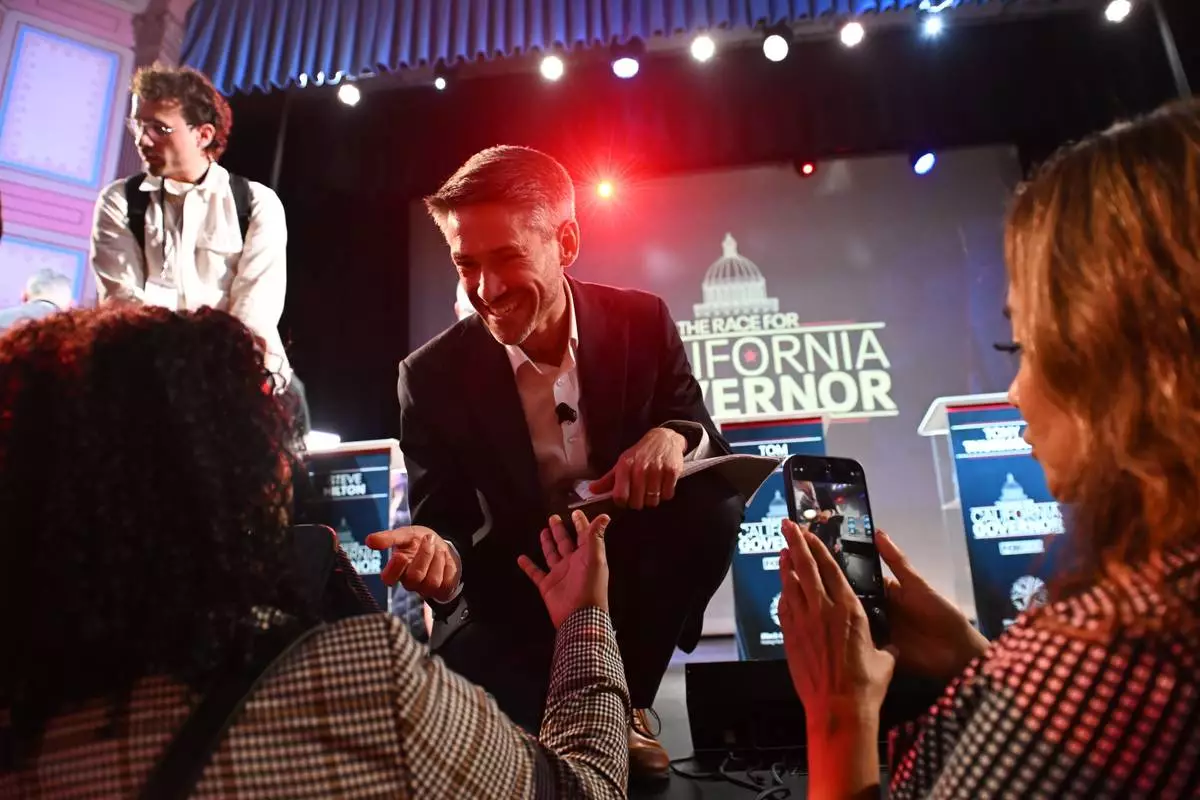

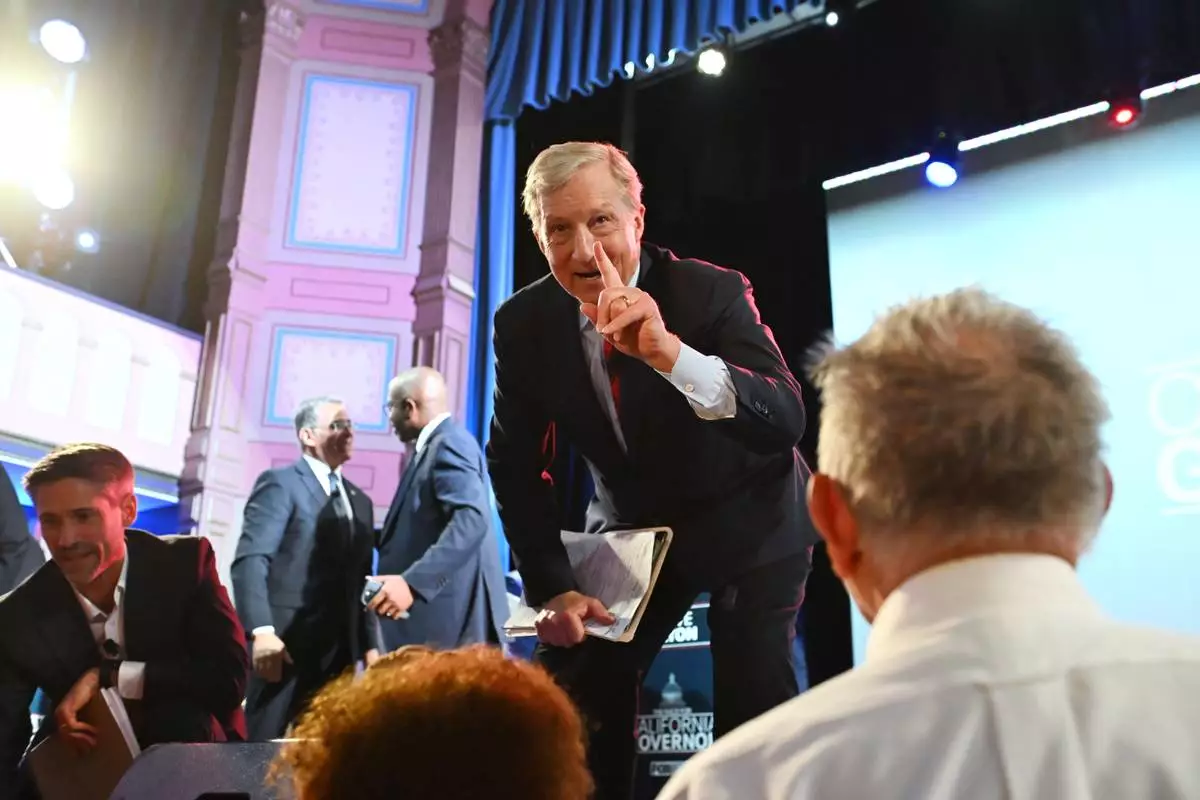

Tom Steyer, right, and Matt Mahan talk to attendees after the California gubernatorial candidate debate Tuesday, Feb. 3, 2026, in San Francisco. (AP Photo/Laure Andrillon)

From left, Xavier Becerra, Steve Hilton, Matt Mahan, Tom Steyer, Tony Thurmond, Antonio Villaraigosa and Betty Yee stand on the stage during the California gubernatorial candidate debate Tuesday, Feb. 3, 2026, in San Francisco. (AP Photo/Laure Andrillon)

FILE - Rep. Eric Swalwell, D-Calif., speaks to reporters after a campaign event on Proposition 50 in San Francisco, Nov. 3, 2025. (AP Photo/Jeff Chiu, File)

Matt Mahan talks to attendees after the California gubernatorial candidate debate Tuesday, Feb. 3, 2026, in San Francisco. (AP Photo/Laure Andrillon)

FILE - U.S. Rep. Katie Porter, D-Calif., waves at supporters at an election party, March 5, 2024, in Long Beach, Calif. (AP Photo/Damian Dovarganes, File)