NASHVILLE, Tenn. (AP) — Highlights from a trove of more than 200 love letters that tell the story of a couple's courtship and marriage during World War II are now on display digitally through the Nashville Public Library, offering an intimate picture of love during wartime.

The letters by William Raymond Whittaker and Jane Dean were found in a Nashville home that had belonged to Jane and her siblings. They were donated in 2016 to the Metro Nashville Archives.

Click to Gallery

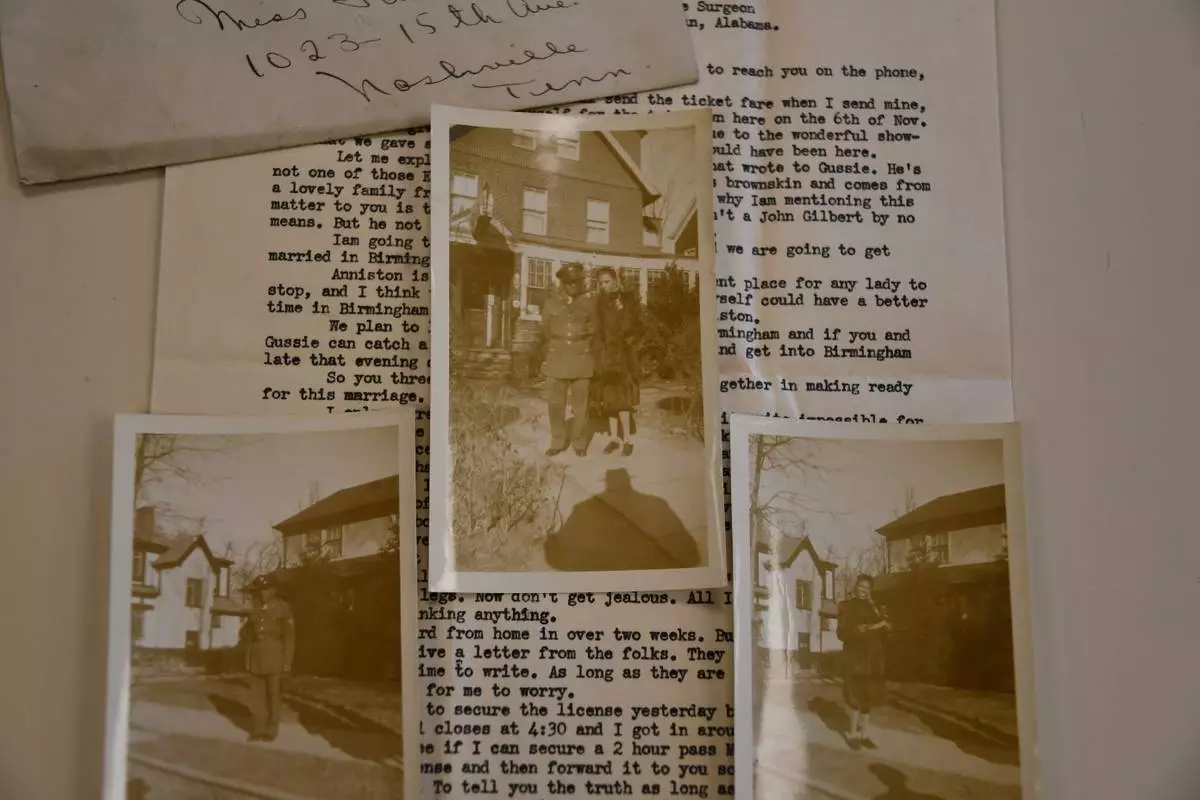

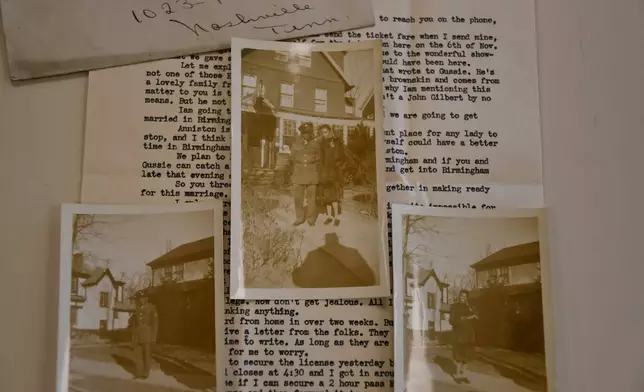

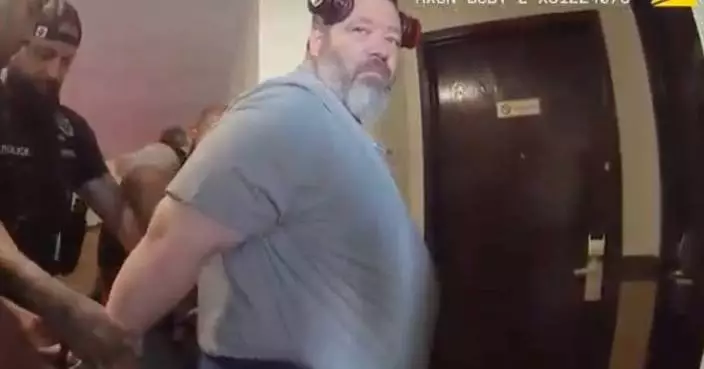

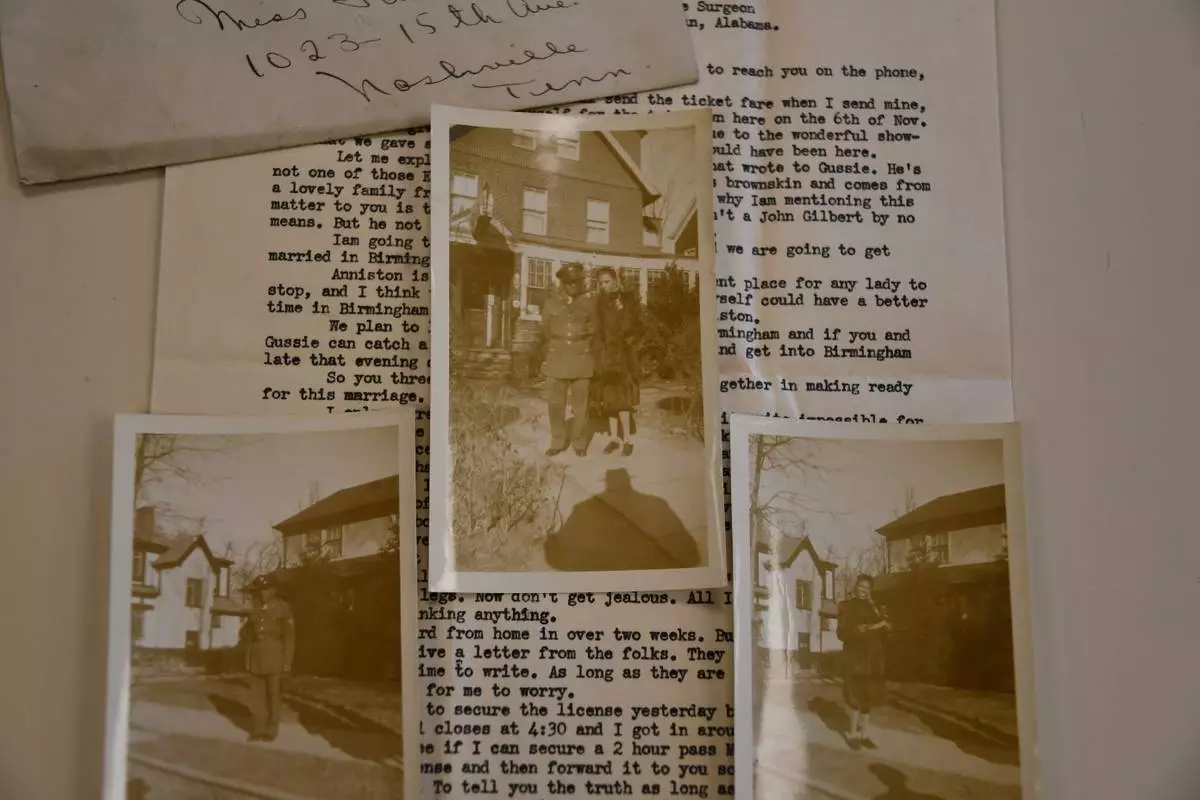

Pictures of William Raymond Whittaker and his wife, Jane Dean Whittaker, are on top of letters the two of them wrote to each other while he was serving in the military, photographed Monday, Feb. 9, 2026, in Nashville, Tenn. (AP Photo/Kristin M. Hall)

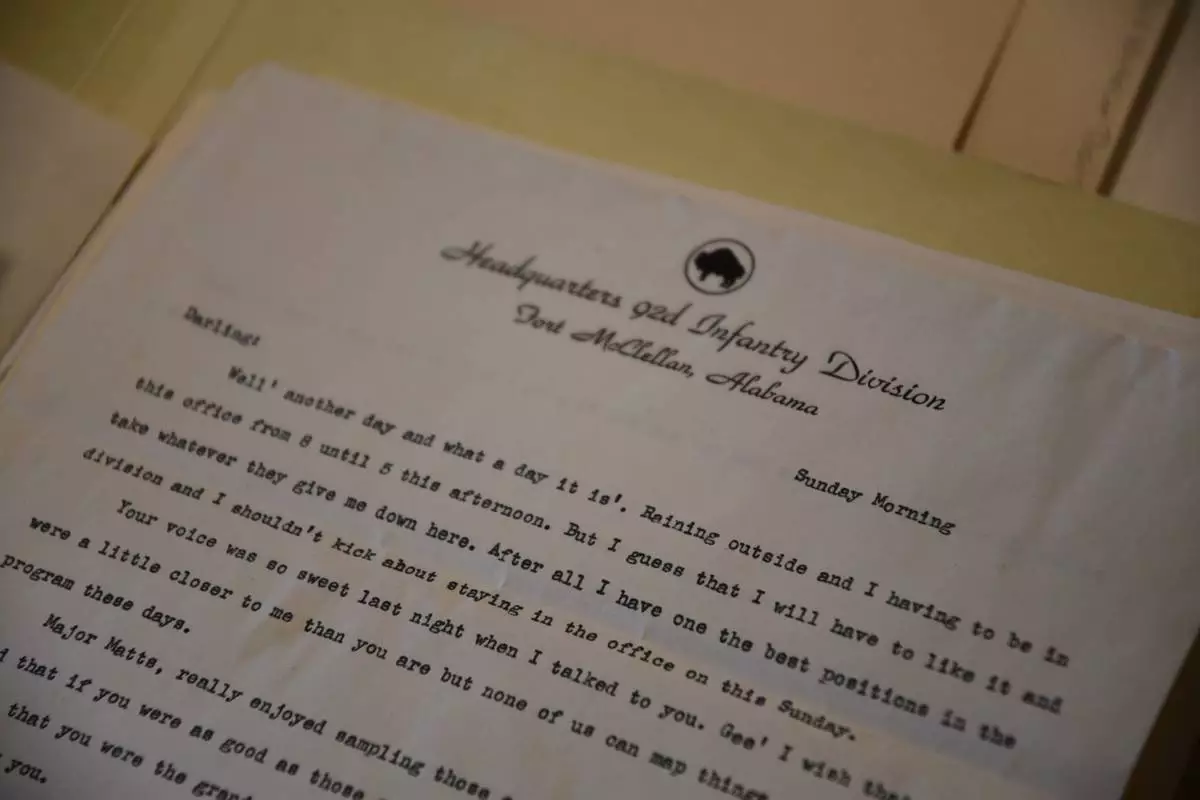

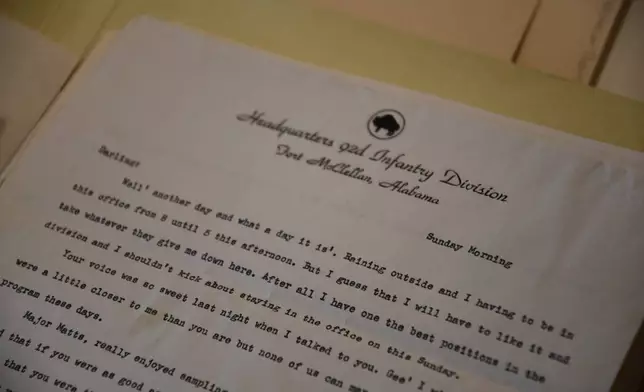

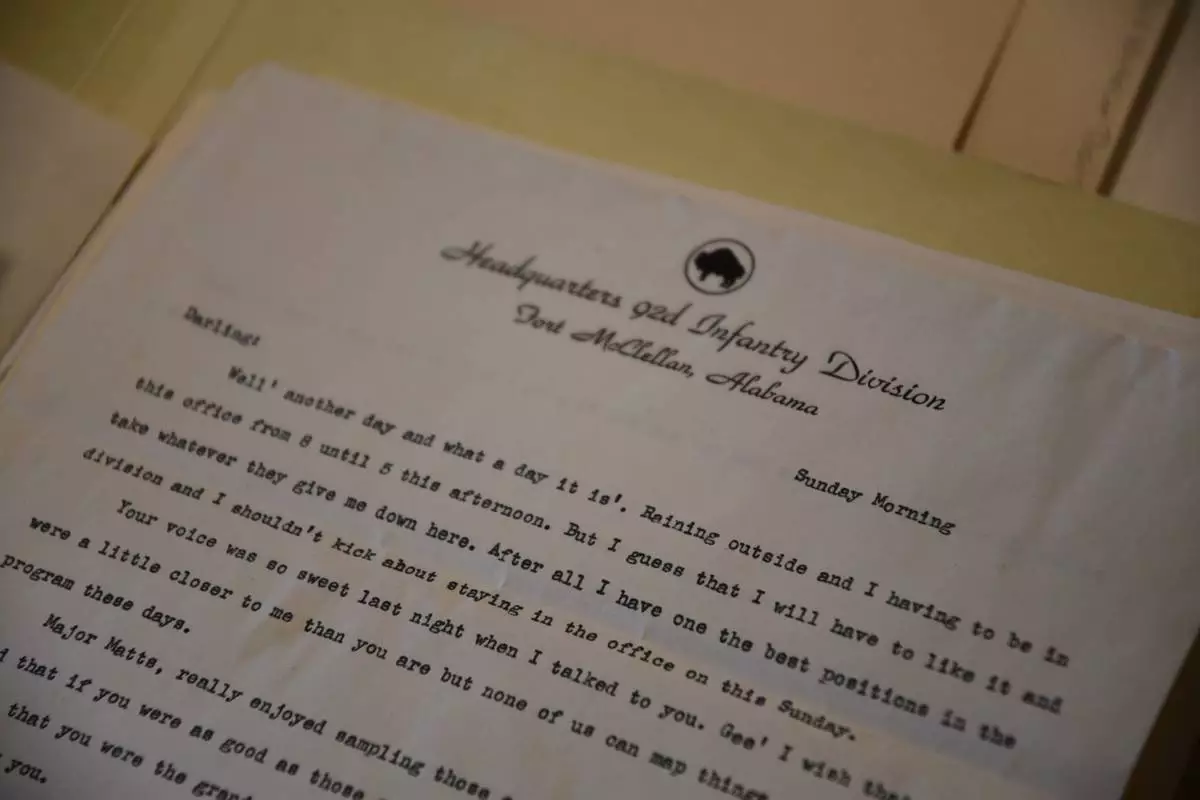

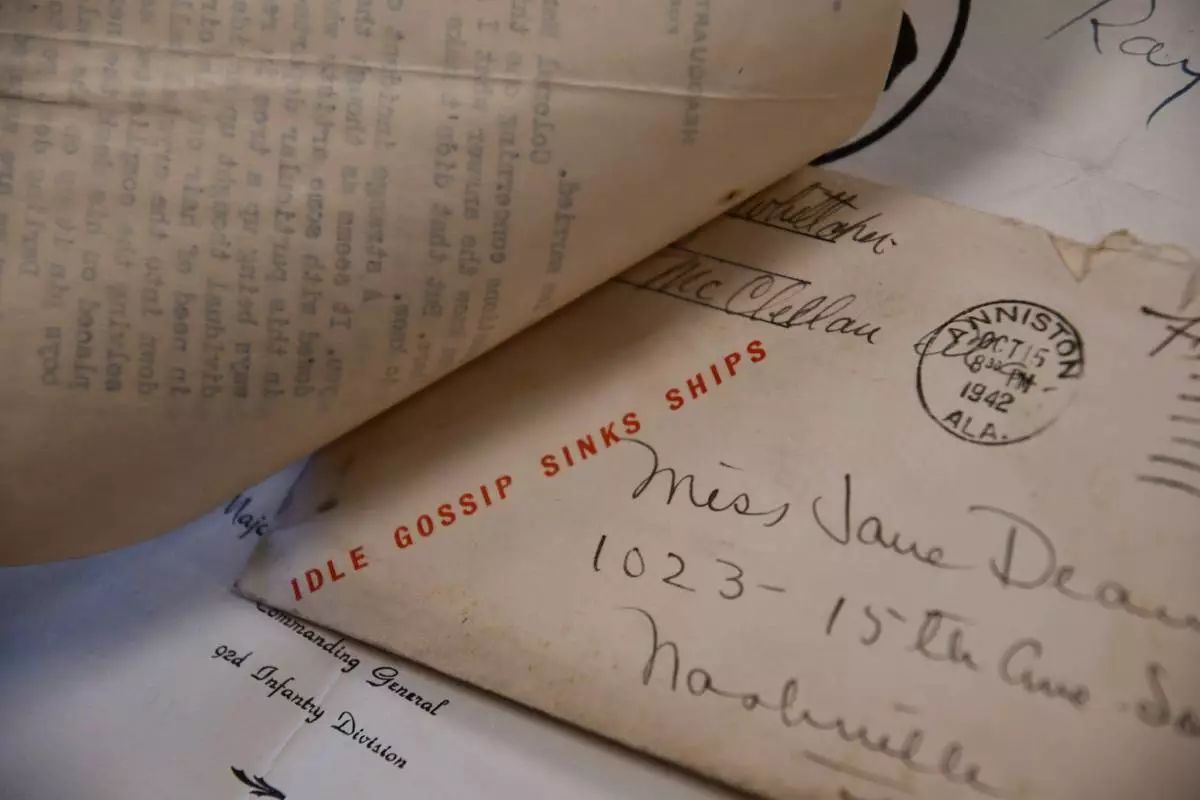

A letter from a soldier assigned to the 92nd Infantry Division, an all-Black military unit during World War II, to his wife in Nashville is seen Monday, Feb. 9, 2026 in Nashville, Tenn. (AP Photo/Kristin M. Hall)

In this digital scan of an undated photo provided by The Nashville Public Library, William Raymond Whittaker, left, and his wife Jane Dean Whittaker stand for a photo in Nashville, Tenn. (The Nashville Public Library via AP)

Archivist Kelley Sirko looks at love letters between a Black soldier and his wife during World War II that are part of a digital exhibit on Monday, Feb. 9, 2026 in Nashville, Tenn. (AP Photo/Kristin M. Hall)

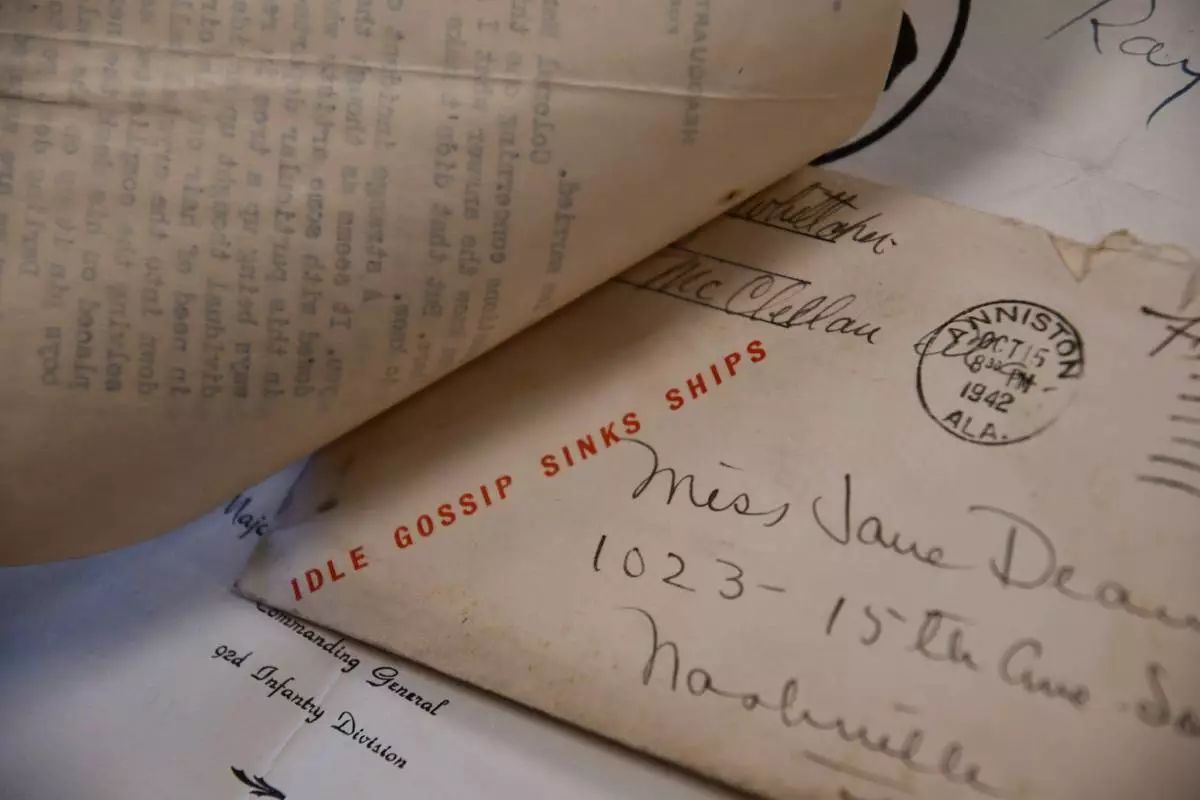

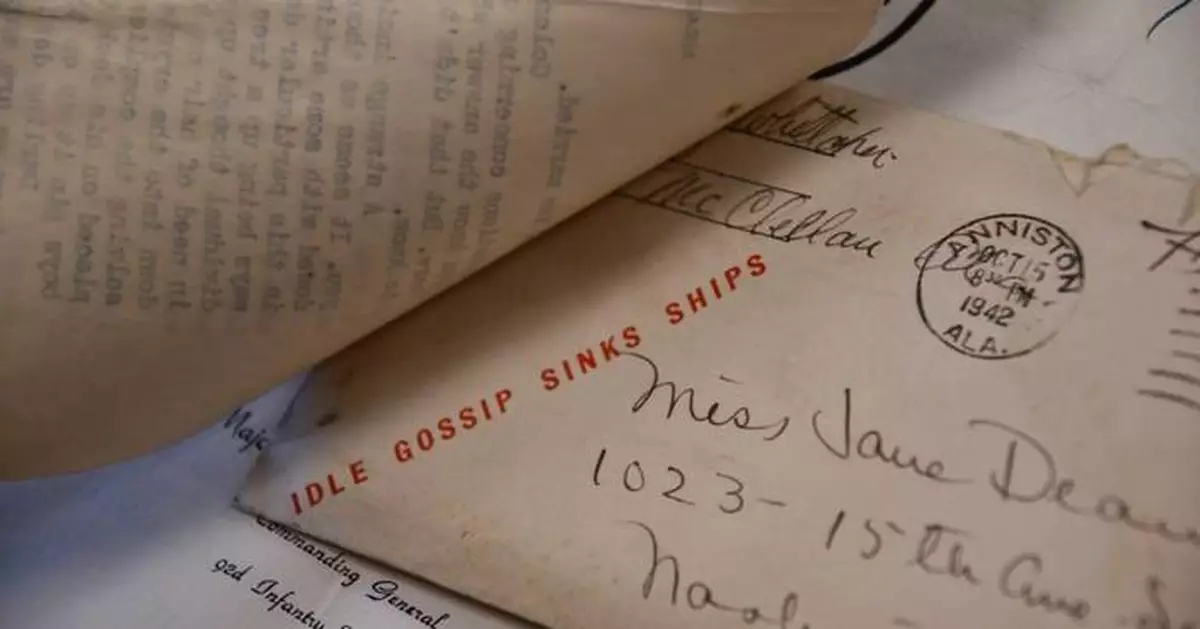

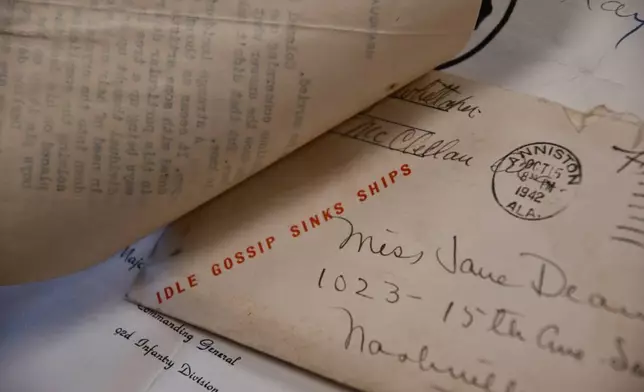

An envelope from a Black soldier stationed in Alabama written to his wife in Nashville in 1942 shows a stamp that says "Idle Gossip Sinks Ships" Monday, Feb. 9, 2026 in Nashville, Tenn. (AP Photo/Kristin M. Hall)

Whittaker, who went by Ray, was from New Rochelle, New York. He moved to the Tennessee capital to attend the historically Black Meharry Medical College, according to the library's metropolitan archivist, Kelley Sirko. That's where he met and dated Jane, another student at the college.

The pair lost touch when Ray left Nashville. In the summer of 1942 he was drafted into the Army. Stationed at Fort Huachuca in Arizona, he decided to reestablish contact with Jane, who was then working as a medical lab technician at Vanderbilt University.

The library doesn't have Ray's first letter to Jane, but it does have her reply. She greets him somewhat formally as “Dear Wm R.”

“It sure was a pleasant and sad surprise to hear from you," she writes on July 30, 1942. "Pleasant because you will always hold a place in my heart and its nice to know you think of me once in a while. Sad because you are in the armed forces — maybe I shouldn’t say that but war is so uncertain, however I’m proud to know that you are doing your bit for your country.”

Jane then goes on to list — perhaps as a hint? — a string of mutual acquaintances who have gotten married recently, noting those who have had children or are rumored to be having children. She signs off, “Write, wire or call me real soon — Lovingly Jane.”

“You can’t help but smile when you read through these letters,” Sirko said. “You really can’t. And this was just such an intimate look at two regular people during a really complicated time in our history.”

Sirko said Nashville archivists have not been able to locate any living relatives of Ray and Jane, so most of what they know about them is from the letters. The couple did not have any children, according to an obituary for Ray, who died in Nashville in 1989.

The donation also included a few photographs and Ray's patch from the historically Black fraternity Alpha Phi Alpha.

Beyond a love story, the collection gives "this in-the-moment perspective of ... what it’s like just navigating certain racial issues, certain gender issues, their work, the life of a soldier, all of these things," Sirko said. That's why the archivists wanted to make it more accessible to the public.

Just two months after the first letters, the romance has heated up. Ray has been assigned to Fort McClellan in Alabama, where he will help organize the reactivated — and segregated — 92nd Infantry Division, which went on to see combat in Europe.

In an undated letter from September 1942, he tells Jane, “I have something very important to tell you when I do see you and you will be surprise to know as to what it is.

"I might even ask you to marry me. One never knows.”

He teases her by saying that if he goes to officer training school, he will be able to “draw down a fat juicey salary” — about $280 a month if he is married and $175 if single.

“Really I can't leave my excess amount of money to the government and must have someone to help me spend it," he writes.

At first Jane is skeptical. “What makes you think you still love me?” she asks on Sept. 23. “Is it that you are lonesome and a long way from home. I’m sure I want you to love me but not under those conditions.”

A Sept. 24 letter from Ray is more serious. “Events are changing so rapidly these days that one can't really plan for the future. But I am going to make a decisive decision in matters of most importances," he writes.

Ray says that he had thought he and Jane could not be together because they lived so far apart. He says he dated other women but “I didn’t find the companionship and love that I so dearly wanted to find. All I ran into was trouble and more trouble.”

Soon Ray wins her over, and they are married on Nov. 7 in Birmingham.

In a letter from Nov. 9, Jane addresses Ray as “my darling husband.” She is rapturous about the marriage but sad that the couple has to remain apart for now. She has already returned to her job and family in Nashville while he has returned to the Army base.

“It’s a wonderful thing to have such and sweet and lovely husband. Darling you’ll never know how much I love you. The only regret is that we didn't marry years ago... As it is now things are so uncertain and we are not together but such a few happy hours. But maybe this old war will soon be over and we can be together for always."

She concludes, “Darling be sweet and write to me soon. I want a letter from my husband. Remember I’ll always love you. Always — from Your Wife”

Pictures of William Raymond Whittaker and his wife, Jane Dean Whittaker, are on top of letters the two of them wrote to each other while he was serving in the military, photographed Monday, Feb. 9, 2026, in Nashville, Tenn. (AP Photo/Kristin M. Hall)

A letter from a soldier assigned to the 92nd Infantry Division, an all-Black military unit during World War II, to his wife in Nashville is seen Monday, Feb. 9, 2026 in Nashville, Tenn. (AP Photo/Kristin M. Hall)

In this digital scan of an undated photo provided by The Nashville Public Library, William Raymond Whittaker, left, and his wife Jane Dean Whittaker stand for a photo in Nashville, Tenn. (The Nashville Public Library via AP)

Archivist Kelley Sirko looks at love letters between a Black soldier and his wife during World War II that are part of a digital exhibit on Monday, Feb. 9, 2026 in Nashville, Tenn. (AP Photo/Kristin M. Hall)

An envelope from a Black soldier stationed in Alabama written to his wife in Nashville in 1942 shows a stamp that says "Idle Gossip Sinks Ships" Monday, Feb. 9, 2026 in Nashville, Tenn. (AP Photo/Kristin M. Hall)

DHAKA, Bangladesh (AP) — When Tarique Rahman, the son of a former prime minister of Bangladesh, returned to the country in December after 17 years of self-imposed exile, he declared to his supporters: “I have a plan.”

Rahman returned at a time of upheaval. Bangladesh was seemingly adrift under an interim administration as it inched closer to a nationwide poll. Many Bangladeshis felt his return offered the country a new chance. His fiercest rival, the former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, would be absent from the election after being toppled by a violent student-led revolt in 2024.

Barely two months later, Rahman is widely seen as the front-runner in Thursday’s election. He restated his ambitions at a campaign rally in Dhaka on Monday, arriving at the podium under heavy security as supporters spilled into a public park, dancing and cheering.

“The main goal and objective of this plan is to change the fate of the people and of this country,” he told the crowd.

That task will not be easy for whoever wins.

The election in Bangladesh follows a tumultuous period that has been marked by mob violence, rising religious intolerance, attacks on the press, the rise of Islamists and the fraying of the rule of law. A fair election will be a major challenge. Governing in its aftermath may prove an even sterner test for democratic institutions weakened by more than a decade of disputed polls and shrinking political space.

“An election with relatively little violence in which people are able to vote freely and all sides accept the outcome would be a significant step forward,” said Thomas Kean of the International Crisis Group, a think tank devoted to resolving conflicts. Yet he cautioned that the restoration of democracy, after facing severe strains under Hasina’s rule, would be a long-term challenge.

That process, Kean said, has “only just started.”

Rahman — the 60-year-old son of former Prime Minister Khaleda Zia — has been promising job creation, greater freedom of speech, law and order, and an end to corruption. His campaign seeks to portray him as a bulwark of democracy in a political landscape long dominated by entrenched parties, military coups and vote rigging.

Though Rahman never held office in his mother’s governments, many Bangladeshis saw him as wielding considerable influence within her Bangladesh Nationalist Party until her death in December.

BNP’s main opponent is an 11-party coalition led by Jamaat-e-Islami, the country’s foremost Islamist party, still shadowed by its collaboration with Pakistan during the 1971 war of independence. On Monday, its chief Shafiqur Rahman told supporters at a rally that the alliance has come together “with the dream of building a new Bangladesh.”

With Hasina’s Awami League party absent from the poll and calling on its supporters to stay away, Jamaat-e-Islami is seeking to expand its reach. The conservative party claims it would govern with restraint if elected to power, but its ascent has sparked unease, particularly over its views on women. The party chief has said women are biologically weaker than men and should not work eight hours a day like men, raising fears it could restrict the fundamental rights of women.

Anxieties over Bangladesh’s future are echoed particularly by those who were part of the uprising that paved the way for the election.

When Nobel Peace Prize laureate Muhammad Yunus assumed office three days after Hasina’s ouster, there was optimism among many. Later, student leaders of the uprising launched a new political outfit, the National Citizen Party, styling itself as a clean break from the old political order.

That promise faded after the party joined the Jamaat-e-Islami-led alliance, leading to disillusion among some leaders, several of whom quit.

Tasnim Jara, a public health expert who resigned from the NCP and is running as an independent candidate, said the uprising had “opened a window” for people like her to enter politics and help reshape its culture. But that hope faded once the NCP aligned itself with the Islamists.

She said it became hard for her to see how a genuinely new political culture that many in Bangladesh have long sought could emerge from such an arrangement.

“I struggled to see how a new political culture could genuinely thrive within that framework,” she said.

Arafat Imran, a student at Dhaka University, said he joined the uprising expecting change, but feels that the aspirations that led to the protests “have not been realized."

Imran noted that though the uprising brought new political faces, the core machinery of the state — the military, police and bureaucracy — remains largely unchanged.

True reform or meaningful change, Imran said, would require overhauling the entire system, adding that “holding elections every five years alone cannot sustain democracy.”

“Alongside elections, it is essential to guarantee the rule of law and civil rights. Had these been ensured, there might have been grounds for satisfaction regarding the elections,” he said.

Worries have also spilled into other areas crucial to a healthy democracy.

Roksana Anzuman Nicole, a popular Dhaka talk-show host, became a rare media voice during the uprising, challenging security forces as hundreds were killed on the streets.

After Hasina’s ouster, hopes that such freedoms would expand also faded. Nicole is now off air, confined to her home, and fearful for her safety after a heated debate with a guest defending mob attacks led to threats against her, her family and colleagues.

“A major pillar of that movement was the belief that everyone would be able to speak freely, that people would enjoy freedom of expression. Sheikh Hasina left on August 5, and just 10 days later, my dreams collapsed,” she said.

Her experience is shared by others too. In December, a pro-uprising cultural activist was shot dead in central Dhaka, and protesters set fire to the offices of the country’s two largest newspapers, trapping staff inside. Last week, 21 journalists from an online outlet reporting critically on the military were briefly detained.

Many journalists told The Associated Press they have curtailed their movements or stopped going to work altogether. Many have lost their jobs as they have been branded by pro-uprising activists as collaborators of Hasina. Global human rights groups have expressed their concerns over press freedom under the Yunus-led administration.

“A free press is vital for a flourishing democracy,” said Catherine Cooper of the Robert & Ethel Kennedy Human Rights Center, one of the groups observing the election. “Protecting freedom of expression should be a top priority.”

Many Bangladeshis are putting their trust in the election. The vote will also include a referendum for political reforms that include prime ministerial term limits and stronger checks on executive power.

There is, however, uncertainty over how the nation’s democracy would look in the years to come.

Iftekhar Zaman, a Bangladeshi political analyst, said for the first time in 16 years, Bangladeshis will have a genuine chance to vote, after three elections under Hasina were marred by allegations of rigging or opposition boycotts. He described the poll as “extraordinary,” but warned that reinforcing democratic institutions would take time.

Kean of the International Crisis Group said while some of the proposed reforms are “significant and meaningful,” they won’t be enough.

“The political culture has to change as well, and we are only seeing the first signs of that,” he said.

Roksana Anzuman Nicole, a popular Dhaka talk-show host, talks to The Associated Press in Dhaka, Bangladesh, Feb. 5, 2026. (AP Photo/Mahmud Hossain Opu)

National Citizen Party (NCP) convener Nahid Islam, left, talks to Jamaat-e-Islami leader Shafiqur Rahman during an election rally in Dhaka, Bangladesh, on Feb. 9, 2026. (AP Photo/Anupam Nath)

FILE - Protesters celebrate at the Parliament House premise after news of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina's resignation, in Dhaka, Bangladesh, on Aug. 5, 2024. (AP Photo/Fatima Tuj Johora, File)

FILE - Head of the Bangladesh's interim government and Nobel laureate Dr. Muhammad Yunus attends an event during where the signing of a political charter called July National Charter was announced, outside Bangladesh's national parliament complex in Dhaka, Bangladesh, on Oct. 17, 2025. (AP Photo/Mahmud Hossain Opu, File)

Tarique Rahman, the son of former Prime Minister Khaleda Zia and chairman of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), attends an election rally ahead of national election in Dhaka, Bangladesh, on Feb. 8, 2026. (AP Photo/Anupam Nath)