His image is on bank notes and in textbooks in Iran, often as a black-and-white embodiment of the 1979 Islamic Revolution that swept aside the country's shah and forever changed the nation.

But unlike other countries ruled by family dynasties, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini's children and grandchildren have never fully entered politics.

Click to Gallery

In this Tuesday, Jan. 22, 2019, photo, a girl walks past a poster of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, at a mosque where he made speeches, in northern Tehran, Iran. The memory of Khomeini, who died in 1989 at the age of 86, looms large over Tehran today. His image is on bank notes and in textbooks in Iran, often as an embodiment of the 1979 Islamic Revolution that swept aside the country’s shah and forever changed the nation. (AP PhotoVahid Salemi)

In this Saturday, Jan. 19, 2019 photo, people pray at the grave of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini at his shrine, just outside of Tehran, Iran. Khomeini was the face of Iran’s Islamic Revolution, but now his family is largely absent from politics. Part of the reason lies with Khomeini’s own commandments after becoming Iran’s first supreme leader. (AP PhotoEbrahim Noroozi)

In this Saturday, Jan. 19, 2019 photo, a portrait of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini is displayed at his grave, just outside of Tehran, Iran. Khomeini was the face of Iran’s Islamic Revolution His image is on bank notes and in textbooks in Iran, often as a black-and-white embodiment of the 1979 Islamic Revolution that swept aside the country’s shah and forever changed the nation. (AP PhotoEbrahim Noroozi)

In this Tuesday, Jan. 22, 2019, photo, a girl walks past a poster of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, at a mosque where he made speeches, in northern Tehran, Iran. The memory of Khomeini, who died in 1989 at the age of 86, looms large over Tehran today. His image is on bank notes and in textbooks in Iran, often as an embodiment of the 1979 Islamic Revolution that swept aside the country’s shah and forever changed the nation. (AP PhotoVahid Salemi)

In this Saturday, Jan. 19, 2019, photo, the graves of revolutionaries who were killed during 1979 Islamic Revolution, shown at Behesht-e-Zahra cemetery, just outside Tehran, Iran. Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini was the face of Iran’s Islamic Revolution. His image is on bank notes and in textbooks in Iran, often as an embodiment of the Revolution that swept aside the country’s shah and forever changed the nation. (AP PhotoEbrahim Noroozi)

In this Saturday, Jan. 19, 2019 photo, a worker cleans a monument at the place Ayatollah Khomeini gave a speech on his return from 15 years of exile, at Behest-e-Zahra cemetery just outside Tehran, Iran. Ayatollah Khomeini was face of Iran’s revolution, but now his family is largely out of the country’s politics. Khomeini and his wife, Khadijeh Saghafi, had five children and 15 grandchildren. (AP PhotoEbrahim Noroozi)

In this Saturday, Jan. 19, 2019 photo, people pray at the grave of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini at his shrine, just outside of Tehran, Iran. Khomeini was the face of Iran’s Islamic Revolution, but now his family is largely absent from politics. Part of the reason lies with Khomeini’s own commandments after becoming Iran’s first supreme leader. (AP PhotoEbrahim Noroozi)

This Saturday, Jan. 19, 2019 photo, shows the graves of revolutionaries who were killed during 1979 Islamic Revolution, at Behesht-e-Zahra cemetery, just outside Tehran, Iran. Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini was the face of Iran’s Islamic Revolution, but now his family is largely absent from politics. Part of the reason lies with Khomeini’s own commandments after becoming Iran’s first supreme leader. (AP PhotoEbrahim Noroozi)

Part of the reason lies with Khomeini's own commandments after becoming Iran's first supreme leader. The rest likely comes from suspicion in the very system Khomeini set up, even though his name still carries weight today.

In this Saturday, Jan. 19, 2019 photo, people pray at the grave of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini at his shrine, just outside of Tehran, Iran. Khomeini was the face of Iran’s Islamic Revolution, but now his family is largely absent from politics. Part of the reason lies with Khomeini’s own commandments after becoming Iran’s first supreme leader. (AP PhotoEbrahim Noroozi)

"I wish I was living during the Khomeini era," said Mahboobeh Ramazani, 27, who recently visited the mosque attached to the ayatollah's residence, now a tourist attraction in northern Tehran. "He is still my favorite, since he never sought anything for himself and his family members."

The memory of Khomeini, who died in 1989 at the age of 86, literally looms large over Tehran today. His golden-domed mausoleum in southern Tehran is one of the first things people see driving into the city from the airport named for him.

Even the CIA, in a 1983 analysis on him, acknowledged that Iran's revolution could not have happened without him. His tape-recorded sermons circulated through the country in the days leading up to the shah's departure, his calls for supporting the poor striking a populist tone among Iran's struggling masses.

In this Saturday, Jan. 19, 2019 photo, a portrait of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini is displayed at his grave, just outside of Tehran, Iran. Khomeini was the face of Iran’s Islamic Revolution His image is on bank notes and in textbooks in Iran, often as a black-and-white embodiment of the 1979 Islamic Revolution that swept aside the country’s shah and forever changed the nation. (AP PhotoEbrahim Noroozi)

His style also fit one of his mantras: "Islam is politics."

"He uses repetition, rhythm, exaggerated images and cutting political jokes to drive his message home and alters his vocabulary — but not his delivery — to show increased emotion," the CIA wrote. "His monotone exerts a hypnotic effect that is heightened by supporters placed among the audience to lead chanted slogans."

But despite his political success, he insisted that his own family not get involved.

In this Tuesday, Jan. 22, 2019, photo, a girl walks past a poster of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, at a mosque where he made speeches, in northern Tehran, Iran. The memory of Khomeini, who died in 1989 at the age of 86, looms large over Tehran today. His image is on bank notes and in textbooks in Iran, often as an embodiment of the 1979 Islamic Revolution that swept aside the country’s shah and forever changed the nation. (AP PhotoVahid Salemi)

Part of that stemmed from the allegations of corruption that surrounded the family of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, whose relatives enriched themselves through government contracts and the public purse.

The shah's family and royal court became known among protesters and the opposition at the time as a "1,000-member" oligarchy, a reference to their widespread presence in government and the private sector. Khomeini's own mullah father had been killed only months after his birth over his activism targeting wealthy landowners.

"I will that those who are related to me not enter political currents," Khomeini said in 1980 when one of his grandchildren backed Iran's then-embattled liberal President Abolhassan Banisadr. "I do order you based on Shariah not to enter political games."

In this Saturday, Jan. 19, 2019, photo, the graves of revolutionaries who were killed during 1979 Islamic Revolution, shown at Behesht-e-Zahra cemetery, just outside Tehran, Iran. Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini was the face of Iran’s Islamic Revolution. His image is on bank notes and in textbooks in Iran, often as an embodiment of the Revolution that swept aside the country’s shah and forever changed the nation. (AP PhotoEbrahim Noroozi)

Khomeini and his wife, Khadijeh Saghafi, had five children and 15 grandchildren. His daughter, Zahra Mostafavi, later became politically active, but said in 2006 that her father had told her and other family members: "Do not enter politics while I am alive."

"After his death, we decided not to enter" politics, she said. However, she would later publicly write Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei to protest the decision to ban influential President Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani from running in the 2013 election.

Khomeini's family did not stay out of politics for long, in part due to the changes within Iran. A growing youth population demanded jobs and had a different political perspective than their parents' generation. Those demands gave birth to Iran's reformist political movement, which seeks to change Iran's government from within and grant more political freedoms to its people.

In this Saturday, Jan. 19, 2019 photo, a worker cleans a monument at the place Ayatollah Khomeini gave a speech on his return from 15 years of exile, at Behest-e-Zahra cemetery just outside Tehran, Iran. Ayatollah Khomeini was face of Iran’s revolution, but now his family is largely out of the country’s politics. Khomeini and his wife, Khadijeh Saghafi, had five children and 15 grandchildren. (AP PhotoEbrahim Noroozi)

Granddaughter Zahra Eshraghi, whose husband, Mohammad Reza Khatami, was the brother of reformist President Mohammad Khatami and served as deputy speaker of parliament, sought to form her own women's group. Both she and her husband tried to run for parliament in 2004, but were blocked by the Guardian Council, a 12-member panel that vets candidates and routinely rejects those calling for dramatic reform. The council similarly blocked Ali Eshraghi, another Khomeini grandson, in 2008.

Meanwhile, one of Khomeini's great-grandchildren has grown increasingly prominent, in part due to his use of Instagram. Ahmad Khomeini, a 20-year-old Shiite cleric, posts images of himself in both Western attire and the black turban marking him as a direct descendent of the Prophet Muhammad.

He also freely posts images of Khatami, subject of a state-ordered media blackout in Iran, and reformist politician Mir-Hossein Mousavi, who remains under house arrest years after he led Iran's Green Movement following his disputed 2009 election loss to hard-line President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

In this Saturday, Jan. 19, 2019 photo, people pray at the grave of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini at his shrine, just outside of Tehran, Iran. Khomeini was the face of Iran’s Islamic Revolution, but now his family is largely absent from politics. Part of the reason lies with Khomeini’s own commandments after becoming Iran’s first supreme leader. (AP PhotoEbrahim Noroozi)

His father, Hassan Khomeini, another of Khomeini's grandsons, was barred by authorities in 2016 from running for seats on Iran's Assembly of Experts, which can appoint or remove a supreme leader.

But fears about political dynasties persist in Iran. Earlier this year, President Hassan Rouhani described the 1979 Islamic Revolution as being aimed at avoiding having a "son to take the throne after the death of father."

Family members of current supreme leader Khamenei have taken a low-key approach to public life.

This Saturday, Jan. 19, 2019 photo, shows the graves of revolutionaries who were killed during 1979 Islamic Revolution, at Behesht-e-Zahra cemetery, just outside Tehran, Iran. Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini was the face of Iran’s Islamic Revolution, but now his family is largely absent from politics. Part of the reason lies with Khomeini’s own commandments after becoming Iran’s first supreme leader. (AP PhotoEbrahim Noroozi)

Political analyst Amir Mohebian, who heads a conservative think tank in Tehran, believes both Khomeini's ban and the people's anti-monarchy sentiment thwarts the formation of any political dynasties.

"The society is very sensitive toward any kind of dynasties' dominance," he said.

Yet even today, Khomeini remains a powerful figure in the minds of many Iranians.

"Khomeini was great. I joined his revolution despite having a good job, a good life, simply because he said Islam is in danger," said Iraj Khalilzadeh, an 81-year-old retired worker at a shoe factory while recently visiting Khomeini's shrine. "I expect the current government to pay attention to poor people."

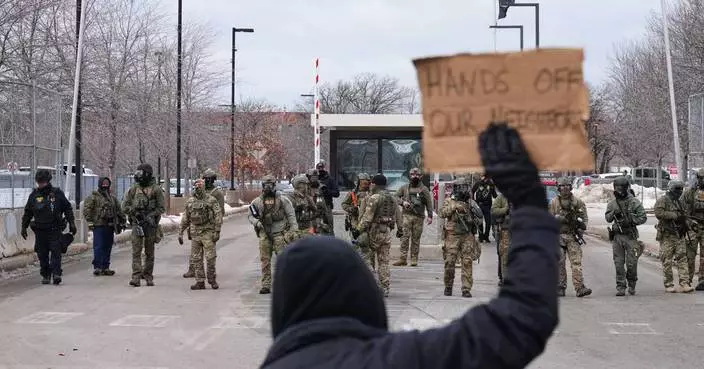

A federal appeals panel on Thursday reversed a lower court decision that released former Columbia University graduate student Mahmoud Khalil from an immigration jail, bringing the government one step closer to detaining and ultimately deporting the Palestinian activist.

The three-judge panel of the 3rd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals didn’t decide the key issue in Khalil’s case: whether the Trump administration’s effort to throw Khalil out of the U.S. over his campus activism and criticism of Israel is unconstitutional.

But in its 2-1 decision, the panel ruled a federal judge in New Jersey didn’t have jurisdiction to decide the matter at this time. Federal law requires the case to fully move through the immigration courts first, before Khalil can challenge the decision, they wrote.

“That scheme ensures that petitioners get just one bite at the apple — not zero or two,” the panel wrote. “But it also means that some petitioners, like Khalil, will have to wait to seek relief for allegedly unlawful government conduct.”

Thursday’s decision marked a major win for the Trump administration’s sweeping campaign to detain and deport noncitizens who joined protests against Israel.

Tricia McLaughlin, a Homeland Security Department spokesperson, called the ruling “a vindication of the rule of law.”

In a statement, she said the department will “work to enforce his lawful removal order” and encouraged Khalil to “self-deport now before he is arrested, deported, and never given a chance to return.”

It was not clear whether the government would seek to detain Khalil, a legal permanent resident, again while his legal challenges continue.

In a statement distributed by the American Civil Liberties Union, Khalil called the appeals ruling “deeply disappointing."

“The door may have been opened for potential re-detainment down the line, but it has not closed our commitment to Palestine and to justice and accountability," he said. "I will continue to fight, through every legal avenue and with every ounce of determination, until my rights, and the rights of others like me, are fully protected.”

Baher Azmy, one of Khalil's lawyers, said the ruling was “contrary to rulings of other federal courts."

“Our legal options are by no means concluded, and we will fight with every available avenue,” he said.

The ACLU said the Trump administration cannot lawfully re-detain Khalil until the order takes formal effect, which won't happen while he can still immediately appeal.

Khalil’s lawyers can request that the panel's decision be set aside and the matter reconsidered by a larger group of judges on the 3rd Circuit Court of Appeals, or they can go to the U.S. Supreme Court.

An outspoken leader of the pro-Palestinian movement at Columbia, Khalil was arrested last March. He then spent three months detained in a Louisiana immigration jail, missing the birth of his first child.

Federal officials have accused Khalil of leading activities “aligned to Hamas,” though they have not presented evidence to support the claim and have not accused him of criminal conduct. They also accused Khalil, 31, of failing to disclose information on his green card application.

The government justified the arrest under a seldom-used statute that allows for the expulsion of noncitizens whose beliefs are deemed to pose a threat to U.S. foreign policy interests.

In June, a federal judge in New Jersey ruled that justification would likely be declared unconstitutional and ordered Khalil released.

President Donald Trump's administration appealed that ruling, arguing the deportation decision should fall to an immigration judge, rather than a federal court.

Khalil has dismissed the allegations as “baseless and ridiculous,” framing his arrest and detention as a “direct consequence of exercising my right to free speech as I advocated for a free Palestine and an end to the genocide in Gaza.”

New York City’s new mayor, Zohran Mamdani, said on social media Thursday that Khalil should remain free.

“Last year’s arrest of Mahmoud Khalil was more than just a chilling act of political repression, it was an attack on all of our constitutional rights,” Mamdani wrote on X. “Now, as the crackdown on pro-Palestinian free speech continues, Mahmoud is being threatened with rearrest. Mahmoud is free — and must remain free.”

Judge Arianna Freeman dissented Thursday, writing that her colleagues were holding Khalil to the wrong legal standard. Khalil, she wrote, is raising “now-or-never claims” that can be handled at the district court level, even though his immigration case isn't complete.

Both judges who ruled against Khalil, Thomas Hardiman and Stephanos Bibas, were Republican appointees. President George W. Bush appointed Hardiman to the 3rd Circuit, while Trump appointed Bibas. President Joe Biden, a Democrat, appointed Freeman.

The two-judge majority rejected Freeman's worry that their decision would leave Khalil with no remedy for unconstitutional immigration detention, even if he later can appeal.

“But our legal system routinely forces petitioners — even those with meritorious claims — to wait to raise their arguments," the judges wrote.

The decision comes as an appeals board in the immigration court system weighs a previous order that found Khalil could be deported to Algeria, where he maintains citizenship through a distant relative, or Syria, where he was born in a refugee camp to a Palestinian family.

His attorneys have said he faces mortal danger if forced to return to either country.

Associated Press writers Larry Neumeister and Anthony Izaguirre contributed to this story.

FILE - Palestinian activist Mahmoud Khalil holds a news conference outside Federal Court on Tuesday, Oct. 21, 2025 in Philadelphia (AP Photo/Matt Rourke, File)