Luna Fenner was born with a distinctive mark on her face known as a giant congenital melanocytic nevus

A mum whose baby girl has a unique black birthmark covering most of her face in the shape of a butterfly, or batman mask, has hit back at cruel strangers who’ve dubbed the adorable tot “a monster who should be killed”.

Carol Fenner, 35, and her partner Thiago Tavares, 32, were initially shocked when their four-month-old daughter Luna Fenner was born with the distinctive mark, which is known as a giant congenital melanocytic nevus (GCMN) and affects just one in 20,000 newborns worldwide.

Worryingly, doctors warned it could be cancerous, but thankfully, an MRI scan soon showed it was not.

Setting up an Instagram page to help raise awareness of birthmarks, Carol, of South Florida, USA, has been buoyed by positive comments, with many of her 70,000 followers sweetly dubbing Luna a “little butterfly.”

But shockingly, the baby – Carol and Thiago’s first child – has also been subject to horrific trolling.

Carol, who worked in sales before Luna was born, said: “A lot of her followers call her little butterfly because of the shape of her birthmark.”

She continued: “We were even sent pictures of people from all over the world who had painted their faces like Luna’s. When I saw them, I was overcome with emotion that they had stopped what they were doing to try and send us positive thoughts.

“But we also get some horrible comments. The worst we had was a man who said, ‘Wouldn’t it be better if we killed her than lived so close to a monster like Luna?’

“I think people are shocked when they see her, and I would be too, but I just want people to think about their reaction.”

Carol, who is originally from Brasilia, Brazil, but has lived in the US for eight years, told how, when Luna first arrived into the world on March 7, she had no idea what her little one’s birthmark was.

Appearing concerned, doctors whisked the newborn away to investigate.

“Two minutes after they took her away, a doctor came and said that we had to prepare for it being cancer. It was like, ‘Oh my God, what is happening?’” Carol recalled.”

Carol added: “It’s so rare the doctors didn’t know what to do. They weren’t prepared for it.”

Carol, a diabetic, explained that, having fallen ill with out-of-control blood sugar levels following the stress of a 48-hour labour, she was too ill to see Luna again until she was two days old.

Meanwhile, she frantically searched the web for information about what the mark could mean.

She continued: “I was asking the doctors if it could be something like measles, but they warned me to prepare for something bad like cancer. It was so frightening to keep hearing that word.

“It’s impossible to know before babies are born whether they will have this mark. We had a 4D scan, which showed that she had a lot of hair, but nothing to show she had a birthmark.”

Luna, whose name means ‘moon’ and ‘light’, had an MRI scan on her neck, face and brain when she was six days old, with the results three days later confirming the mark was not cancerous.

A visiting dermatologist to the hospital then diagnosed her with a CMN.

Carol added: “We breathed such a sigh of relief and were discharged and told to visit the dermatologist in three months’ time. But I didn’t want to wait, so within a month we visited the first plastic surgeon.”

According to the website of charity Caring Matters Now, around one per cent of newborns have a CMN, with one in 20,000 babies diagnosed with the same giant form as Luna.

The birthmark is caused by genetic changes while the baby is in the womb, the charity says, and is not inherited. It has a one to two per cent chance of developing into a malignant melanoma over the newborn’s lifetime.

Carol and Thiago, a construction worker, have been told that their daughter’s mark, which is also hairy and needs trimming with a nose hair trimmer once a week, will grow proportionally as she gets older.

Though it is not painful, nor does it impact her sight, it can get very itchy and needs to be moisturised regularly.

After weighing up both the risk of the CMN one day developing into a cancerous melanoma, and fears that Luna may be targeted by bullies when she gets older, her parents decided to try and find a surgeon who could remove the mark while she is still too young to remember having an operation.

Carol said: “I’m so worried about her getting bullied and what it would do to her self-esteem.

“We receive hundreds of messages a day through our Instagram. About 80 per cent of those are from people saying that they have the same condition and have suffered from years of bullying. I don’t want my daughter to have to go through that.”

“When we go out, people will stare and point, or bring people over to look at her. It’s so horrible,” Carol explained.

“In the past, we’ve been asked if she is contagious, and strangers have even called her disgusting. I just can’t face Luna having to deal with that kind of thing at school.”

After searching across the US, the family found a medic in New York keen to take on the case.

But, because Luna, who also has a coin size mark on her bottom and a few small spots on her legs, could need five or six surgeries over the next three years, costs could reach a mammoth $500,000 (£401,230).

What’s more, the ops – which would include repeated skin grafts after the mole is removed from Luna’s face – may not be covered by health insurance, as they will be taking place in a different state to where the family live.

In a desperate bid to help raise cash, their loved ones have set up a GoFundMe page, which has already gathered almost $20,000 (£16,048) worth of donations.

Carol said: “We saw many surgeons telling us different things, because what Luna has is so rare. Some would say they need to wait until she’s older, and others that it needs doing straight away.

“Some suggested laser surgery, instead of just removing it, but I’ve spoken to another mother with a child with marks a lot lighter than Luna’s, and she had had 30 laser sessions under general anaesthetic and needed another 50.

“If we have it removed when Luna is 10 years old, it’s likely that she would remember it. And the results would not be as good as there would likely be more scarring.”

For now, Carol continues to raise awareness via her Instagram page, and hopes Luna will take comfort from all the positive messages when she is older.

She explained: “I want to show Luna that a lot of people were sending her good vibes, and to show other people difference and what beauty looks like.

“To us, Luna will always be beautiful and we tell her all the time.”

She added: “She is such a calm baby, she never cries and she’s really happy. She smiles all the time.

“She is like any other baby but we do need to avoid the sun. It’s really important to protect the mark using lots of sunblock and avoiding being directly in the sun.

“We’re in this situation now where we really don’t know if we’re going to get the surgery. But I will keep trying. I want Luna to know when she’s older that I’m doing everything I can to help her.”

Dr Barry Zide, professor of plastic surgery at NYU Langone Health in New York, USA, who has 30 years’ experience, explained Luna may need five or six operations starting immediately.

He said the procedure would involve placing tissue expanders to try and promote the growth of healthy skin, removing the majority of the nevus starting with the cheeks and forehead and using skin grafts to complete the procedure.

Dr Zide added: “The chances of malignancy here are very low but the key is to get this off with minimal complications before Luna starts school.

He added: “This child has a great chance to look very well if the procedures are performed with a planned approach.”

To donate click here and you can follow Luna on Instagram @luna.love.hope

“My year of unraveling” is how a despairing Christy Morrill described nightmarish months when his immune system hijacked his brain.

What’s called autoimmune encephalitis attacks the organ that makes us “us,” and it can appear out of the blue.

Morrill went for a bike ride with friends along the California coast, stopping for lunch, and they noticed nothing wrong. Neither did Morrill until his wife asked how it went — and he'd forgotten. Morrill would get worse before he got better. “Unhinged” and “fighting to see light,” he wrote as delusions set in and holes in his memory grew.

Of all the ways our immune system can run amok and damage the body instead of protecting it, autoimmune encephalitis is one of the most unfathomable. Seemingly healthy people abruptly spiral with confusion, memory loss, seizures, even psychosis.

But doctors are getting better at identifying it, thanks to discoveries of a growing list of the rogue antibodies responsible that, if found in blood and spinal fluid, aid diagnosis. Every year new culprit antibodies are being uncovered, said Dr. Sam Horng, a neurologist at Mount Sinai Health System in New York who has cared for patients with multiple forms of this mysterious disease.

And while treatment today involves general ways to fight the inflammation, two major clinical trials are underway aiming for more targeted therapy.

Still, it's tricky. Symptoms can be mistaken for psychiatric or other neurologic disorders, delaying proper treatment.

“When someone’s having new changes in their mental status, they’re worsening and if there’s sort of like a bizarre quality to it, that’s something that kind of tips our suspicion,” Horng said. “It’s important not to miss a treatable condition.”

With early diagnosis and care, some patients fully recover. Others like Morrill recover normal daily functioning but grapple with some lasting damage — in his case, lost decades of “autobiographical” memories. This 72-year-old literature major can still spout facts and figures learned long ago, and he makes new memories every day. But even family photos can’t help him recall pivotal moments in his own life.

“I remember ‘Ulysses’ is published in Paris in 1922 at Sylvia Beach’s bookstore. Why do I remember that, which is of no use to me anymore, and yet I can’t remember my son’s wedding?” Morrill wonders.

Encephalitis means the brain is inflamed and symptoms can vary from mild to life-threatening. Infections are a common cause, typically requiring treatment of the underlying virus or bacteria. But when that's ruled out, an autoimmune cause has to be considered, Horng said, especially when symptoms arise suddenly.

The umbrella term autoimmune encephalitis covers a group of diseases with weird-sounding names based on the antibody fueling it, such as anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis.

While they're not new diseases, that one got a name in 2007 when Dr. Josep Dalmau, then at the University of Pennsylvania, discovered the first culprit antibody, sparking a hunt for more.

That anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis tends to strike younger women and, one of the bizarre factors, it’s sometimes triggered by an ovarian “dermoid” cyst.

How? That type of cyst has similarities to some brain tissue, Horng explained. The immune system can develop antibodies recognizing certain proteins from the growth. If those antibodies get into the brain, they can mistakenly target NMDA receptors on healthy brain cells, sparking personality and behavior changes that can include hallucinations.

Different antibodies create different problems depending if they mostly hit memory and mood areas in the brain, or sensory and movement regions.

Altogether, “facets of personhood seem to be impaired," Horng said.

Therapies include filtering harmful antibodies out of patients' blood, infusing healthy ones, and high-dose steroids to calm inflammation.

Those cyst-related antibodies stealthily attacked Kiara Alexander in Charlotte, North Carolina, who’d never heard of the brain illness. She’d brushed off some oddities — a little forgetfulness, zoning out a few minutes — until she found herself in an ambulance because of a seizure.

Maybe dehydration, the first hospital concluded. At a second hospital after a second seizure, a doctor recognized the possible signs, ordering a spinal tap that found the culprit antibodies.

As Alexander's treatment began, other symptoms ramped up. She has little clear memory of the monthlong hospital stay: “They said I would just wake up screaming. What I could remember, it was like a nightmare, like the devil trying to catch me.”

Later Alexander would ask about her 9-year-old daughter and when she could go home — only to forget the answer and ask again.

Alexander feels lucky she was diagnosed quickly, and she got the ovarian cyst removed. But it took over a year to fully recover and return to work full time.

In San Carlos, California, in early 2020, it was taking months to determine what caused Morrill's sudden memory problem. He remembered facts and spoke eloquently but was losing recall of personal events, a weird combination that prompted Dr. Michael Cohen, a neurologist at Sutter Health, to send him for more specialized testing.

“It’s very unusual, I mean extremely unusual, to just complain of a problem with autobiographical memory,” Cohen said. “One has to think about unusual disorders.”

Meanwhile Morrill’s wife, Karen, thought she’d detected subtle seizures — and one finally happened in front of another doctor, helping spur a spinal tap and diagnosis of LGI1-antibody encephalitis.

It’s a type most common in men over age 50. Those rogue antibodies disrupt how neurons signal each other, and MRI scans showed they’d targeted a key memory center.

By then Morrill, who’d spent retirement guiding kayak tours, could no longer safely get on the water. He’d quit reading and as his treatments changed, he’d get agitated with scary delusions.

“I lost total mental capacity and fell apart,” Morrill describes it.

He used haiku to make sense of the incomprehensible, and months into treatment finally wondered if the “meds coursing through me” really were “dousing the fire. Rays of hope?”

The nonprofit Autoimmune Encephalitis Alliance lists about two dozen antibodies — and counting — known to play a role in these brain illnesses so far.

Clinical trials, offered at major medical centers around the country, are testing two drugs now used for other autoimmune diseases to see if tamping down antibody production can ease encephalitis.

More awareness of these rare diseases is critical, said North Carolina's Alexander, who sought out fellow patients. “That's a terrible feeling, feeling like you're alone.”

As for Morrill, five years later he still grieves decades of lost memories: family gatherings, a year spent studying in Scotland, the travel with his wife.

But he’s making new memories with grandkids, is back outdoors — and leads an AE Alliance support group, using his haiku to illustrate the journey from his “unraveling” to “the present is what I have, daybreaks and sunsets” to, finally, “I can sustain hope.”

“I’m reentering some real time of fun, joy,” Morrill said. “I wasn’t shooting for that. I just wanted to be alive.”

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Department of Science Education and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

Kiara Alexander, left, who was hospitalized with autoimmune encephalitis, leaves a grocery store with her daughter Kennedi, Friday, Oct. 10, 2025, in Charlotte, N.C. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

Kiara Alexander, who was hospitalized with autoimmune encephalitis, poses for a photo at her home, Friday, Oct. 10, 2025, in Charlotte, N.C. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

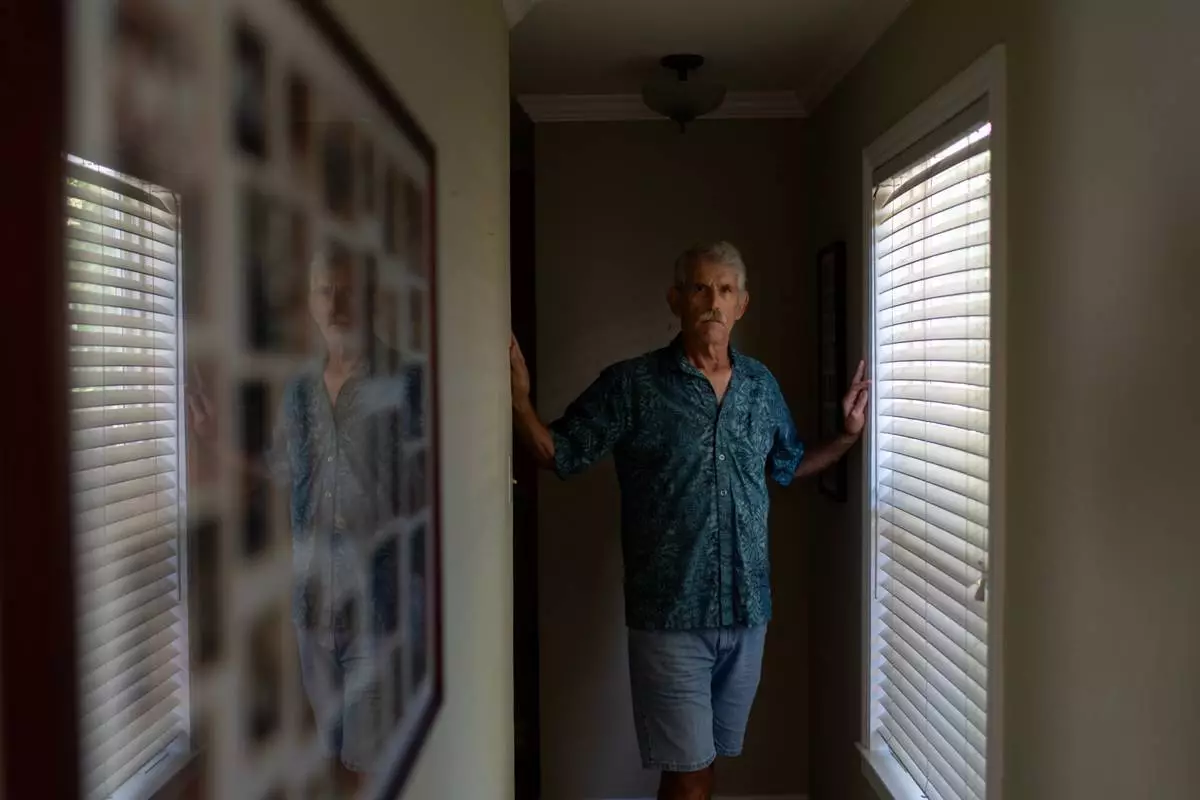

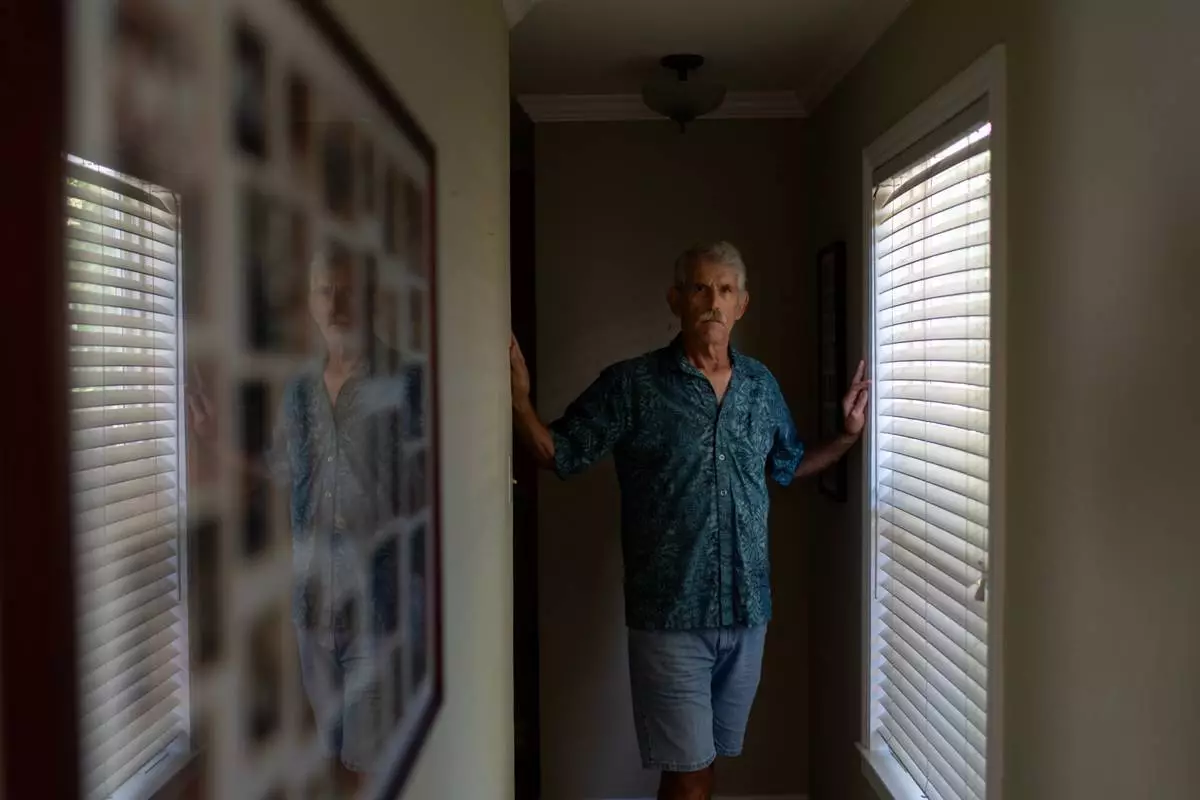

Christy Morrill, 72, who lost decades of memories to autoimmune encephalitis, looks over a photo album of his son's wedding, at his home, Tuesday, Aug. 19, 2025, in San Carlos, Calif. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

Christy Morrill, 72, left, who lost decades of memories to autoimmune encephalitis, looks over family photo albums with, from left, his wife Karen, daughter Caitlin and grandson Colter, at his home, Tuesday, Aug. 19, 2025, in San Carlos, Calif. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

Christy Morrill, 72, who lost decades of memories to autoimmune encephalitis, poses for a photo at his home, Wednesday, Aug. 20, 2025, in San Carlos, Calif. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

Christy Morrill, 72, who lost decades of memories to autoimmune encephalitis, holds up a viewfinder with a slide film of himself as a college student, Wednesday, Aug. 20, 2025, at his home in San Carlos, Calif. (AP Photo/David Goldman)