THE HAGUE, Netherlands (AP) — A panel of judges at the International Criminal Court reported Mongolia to the court's oversight organization on Thursday for failing to arrest Russian President Vladimir Putin when he visited the Asian nation last month.

Putin's visit was his first to a member state of the court since it issued an arrest warrant for him last year on war crimes charges, accusing him of personal responsibility for the abductions of children from Ukraine. Russia is not a member of the court and the Kremlin has rejected the charges.

“States Parties and those accepting the Court’s jurisdiction are duty-bound to arrest and surrender individuals subject to ICC warrants, regardless of official position or nationality,” the court said in a statement.

Putin is wanted by the court for his alleged personal responsibility for the war crime of unlawful deportation of children and unlawful transfer of children from occupied areas of Ukraine to the Russian Federation.

Instead of arresting Putin, Mongolian authorities rolled out the red carpet. The Russian leader was welcomed in the main square of the capital, Ulaanbaatar, by an honor guard dressed in vivid red and blue uniforms styled on those of the personal guard of 13th century ruler Genghis Khan, the founder of the Mongol Empire.

Ahead of the visit, Ukraine had urged Mongolia to hand Putin over to the court in The Hague, and the European Union expressed concern that Mongolia might not execute the warrant.

“In view of the seriousness of Mongolia’s failure to cooperate with the Court, the Chamber deemed it necessary to refer the matter to the Assembly of States Parties,” the court said, referring to its oversight body that meets in December in The Hague.

What the assembly will now do remains unclear. While Putin was in Mongolia, a court said that the organization that is made up of all 124 of the court's member states can “take any measure it deems appropriate.”

FILE - Russian President Vladimir Putin and Mongolian President Ukhnaagiin Khurelsukh, left, attend a welcome ceremony in Sukhbaatar Square in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, Tuesday, Sept. 3, 2024. (Vyacheslav Prokofyev, Sputnik, Kremlin Pool Photo via AP, File)

FILE - Russian President Vladimir Putin, right, walks with Mongolian President Ukhnaagiin Khurelsukh, left, during a welcoming ceremony at Sukhbaatar Square in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, Tuesday, Sept. 3, 2024. (Kristina Kormilitsyna, Sputnik, Kremlin Pool Photo via AP, File)

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. (AP) — An ailing astronaut returned to Earth with three others on Thursday, ending their space station mission more than a month early in NASA’s first medical evacuation.

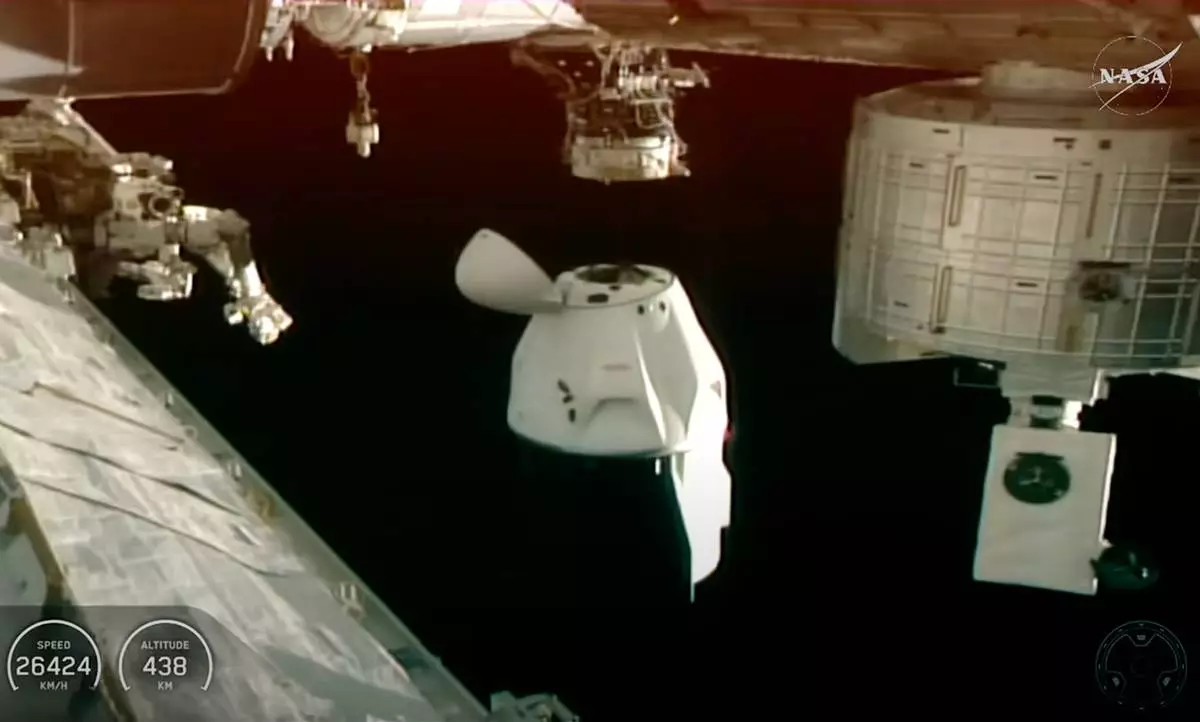

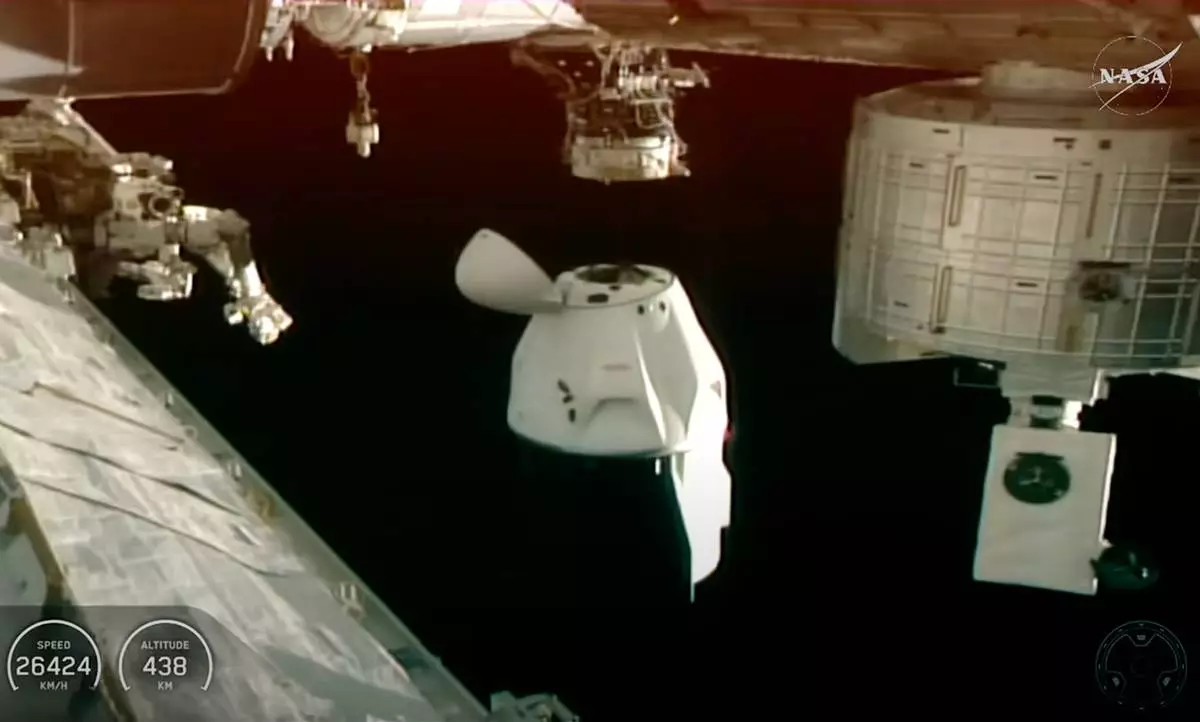

SpaceX guided the capsule to a middle-of-the-night splashdown in the Pacific near San Diego, less than 11 hours after the astronauts exited the International Space Station.

“It’s so good to be home,” said NASA astronaut Zena Cardman, the capsule commander.

It was an unexpected finish to a mission that began in August and left the orbiting lab with only one American and two Russians on board. NASA and SpaceX said they would try to move up the launch of a fresh crew of four; liftoff is currently targeted for mid-February.

Cardman and NASA’s Mike Fincke were joined on the return by Japan’s Kimiya Yui and Russia’s Oleg Platonov. Officials have refused to identify the astronaut who had the health problem or explain what happened, citing medical privacy.

While the astronaut was stable in orbit, NASA wanted them back on Earth as soon as possible to receive proper care and diagnostic testing. The entry and splashdown required no special changes or accommodations, officials said, and the recovery ship had its usual allotment of medical experts on board. It was not immediately known when the astronauts would fly from California to their home base in Houston. Platonov’s return to Moscow was also unclear.

NASA stressed repeatedly over the past week that this was not an emergency. The astronaut fell sick or was injured on Jan. 7, prompting NASA to call off the next day’s spacewalk by Cardman and Fincke, and ultimately resulting in the early return. It was the first time NASA cut short a spaceflight for medical reasons. The Russians had done so decades ago.

The space station has gotten by with three astronauts before, sometimes even with just two. NASA said it will be unable to perform a spacewalk, even for an emergency, until the arrival of the next crew, which has two Americans, one French and one Russian astronaut.

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Department of Science Education and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

This screengrab from video provided by NASA TV shows the SpaceX Dragon departing from the International Space Station shortly after undocking with four NASA Crew-11 members inside on Wednesday, Jan. 14, 2026. (NASA via AP)

This photo provided by NASA shows clockwise from bottom left are, NASA astronaut Mike Fincke, Roscosmos cosmonaut Oleg Platonov, NASA astronaut Zena Cardman, and JAXA (Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency) astronaut Kimiya Yui gathering for a crew portrait wearing their Dragon pressure suits during a suit verification check inside the International Space Station’s Kibo laboratory module, Wednesday, Jan. 14, 2026. (NASA via AP)

This screengrab from video provided by NASA shows recovery vessels approaching the NASA's SpaceX Crew-11 capsule to evacuate one of the crew members after they re-entered the earth in a middle-of-the-night splashdown near San Diego, Calif., Thursday, Jan. 15, 2026. (NASA via AP)

This screengrab from video provided by NASA shows the NASA's SpaceX Crew-11 members re entering the earth in a middle-of-the-night splashdown near San Diego, Calif., Thursday, Jan. 15, 2026. (NASA via AP)

This screengrab from video provided by NASA shows the NASA's SpaceX Crew-11 members re entering the earth in a middle-of-the-night splashdown near San Diego, Calif., Thursday, Jan. 15, 2026. (NASA via AP)