Clint Hill, the Secret Service agent who leaped onto the back of President John F. Kennedy's limousine after the president was shot, then was forced to retire early because he remained haunted by memories of the assassination, has died. He was 93.

Hill died Friday at his home in Belvedere, California, according to his publisher, Gallery Books, an imprint of Simon & Schuster. A cause of death was not given.

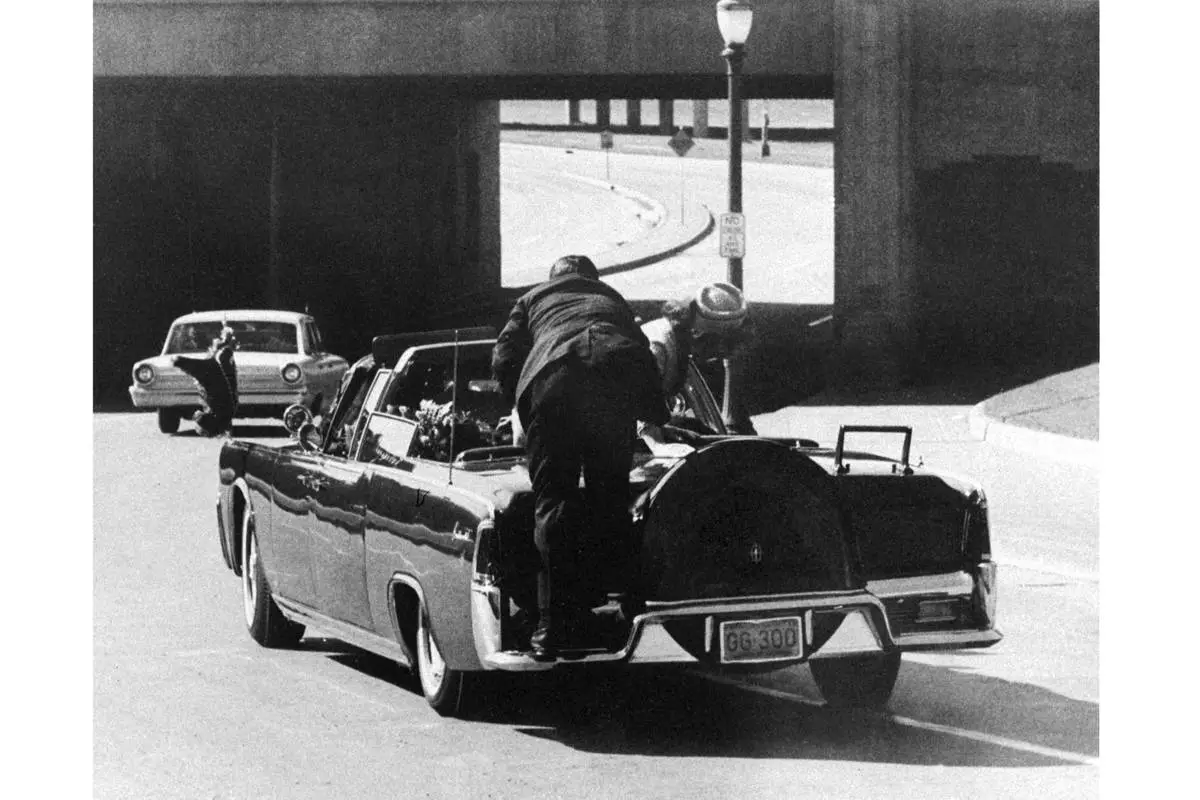

Although few may recognize his name, the footage of Hill, captured on Abraham Zapruder's chilling home movie of the assassination, provided some of the most indelible images of Kennedy's assassination in Dallas on Nov. 22, 1963.

Hill received Secret Service awards and was promoted for his actions that day, but for decades blamed himself for Kennedy's death, saying he didn't react quickly enough and would gladly have given his life to save the president.

"If I had reacted just a little bit quicker. And I could have, I guess," a weeping Hill told Mike Wallace on CBS' 60 Minutes in 1975, shortly after he retired at age 43 at the urging of his doctors. "And I'll live with that to my grave."

It was only in recent years that Hill said he was able to finally start putting the assassination behind him and accept what happened.

On the day of the assassination, Hill was assigned to protect first lady Jacqueline Kennedy, and was riding on the left running board of the follow-up car directly behind the presidential limousine as it made its way through Dealey Plaza.

Hill told the Warren Commission that he reacted after hearing a shot and seeing the president slump in his seat. The president was struck by a fatal headshot before Hill was able to make it to the limousine.

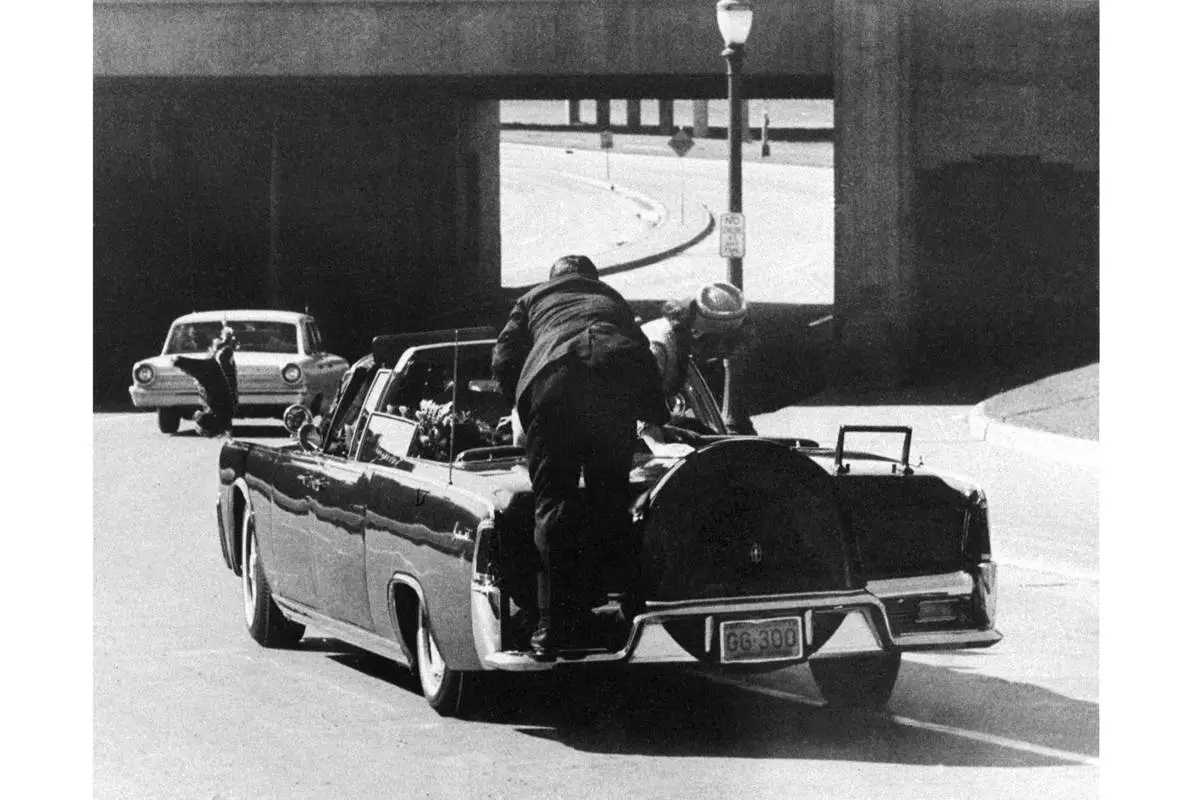

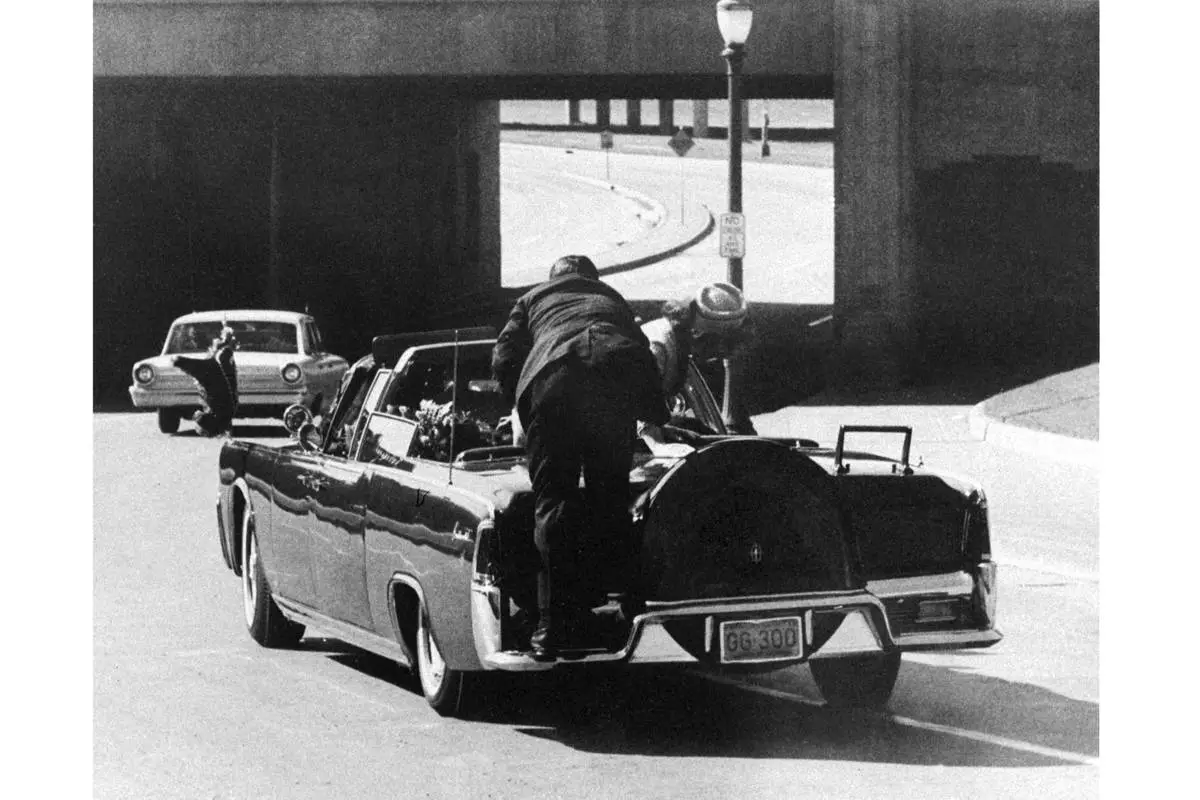

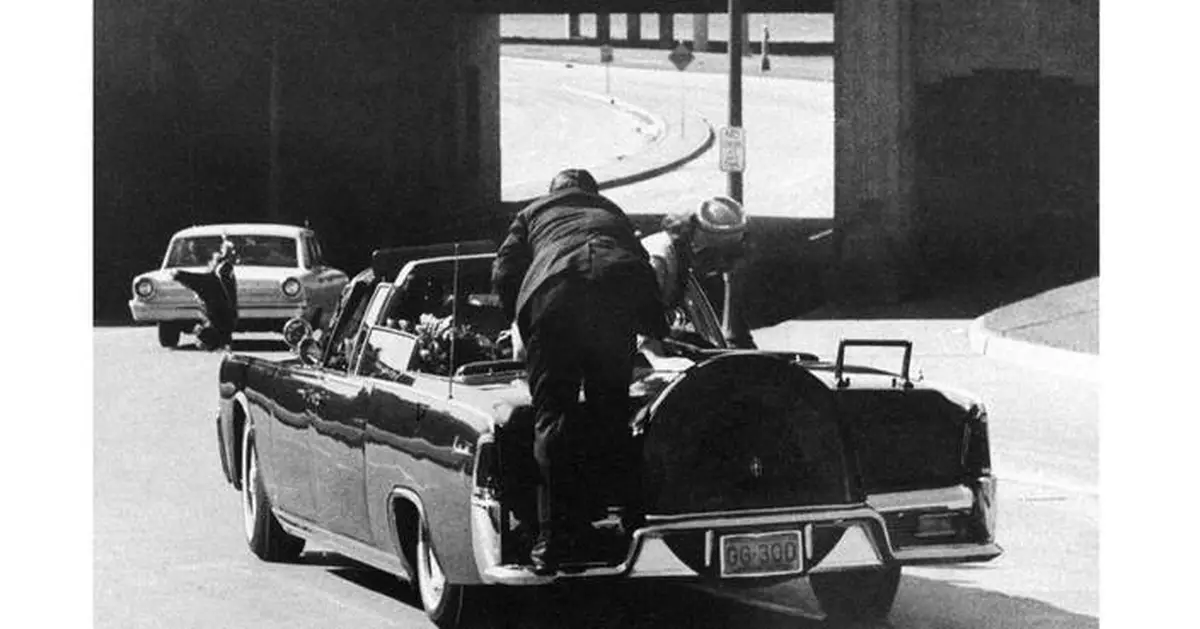

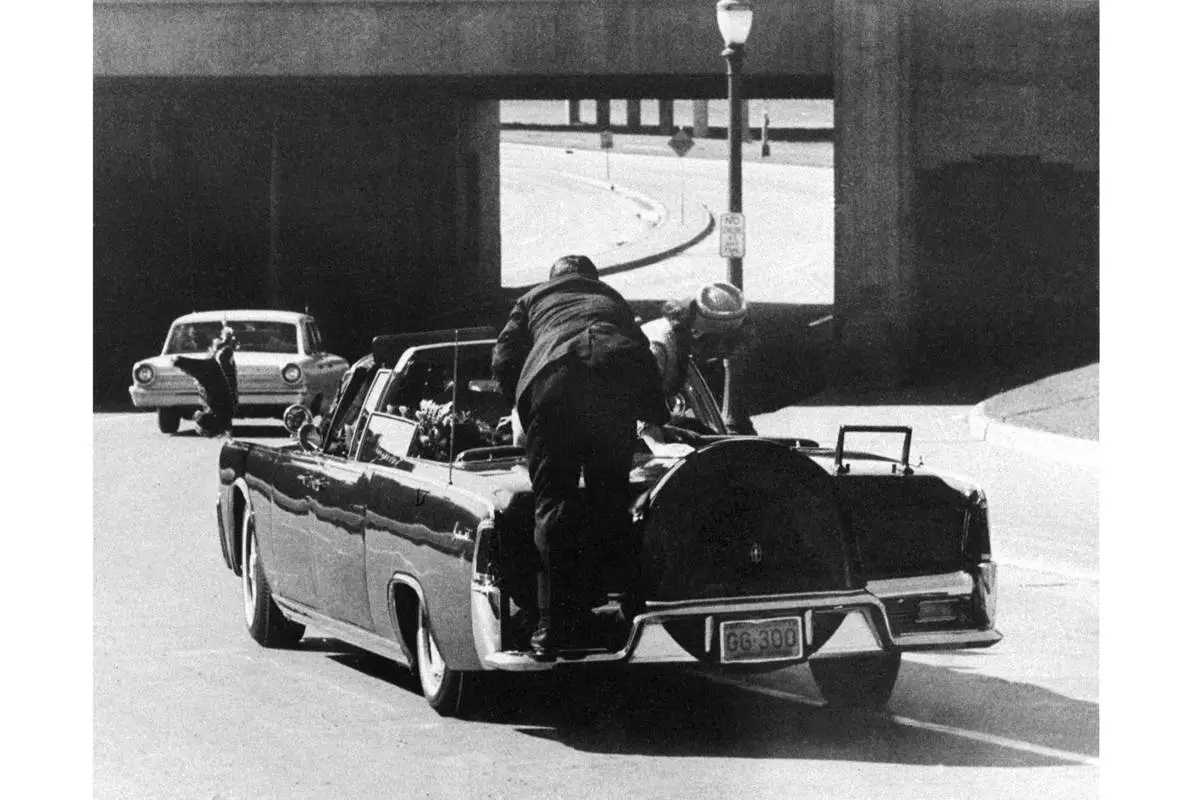

Zapruder's film captured Hill as he leaped from the Secret Service car, grabbed a handle on the limousine's trunk and pulled himself onto it as the driver accelerated. He forced Mrs. Kennedy, who had crawled onto the trunk, back into her seat as the limousine sped off.

Hill later became the agent in charge of the White House protective detail and eventually an assistant director of the Secret Service, retiring because of what he characterized as deep depression and recurring memories of the assassination.

The 1993 Clint Eastwood thriller "In the Line of Fire," about a former Secret Service agent scarred by the JFK assassination, was inspired in part by Hill.

Hill was born in 1932 and grew up in Washburn, North Dakota. He attended Concordia College in Moorhead, Minnesota, served in the Army and worked as a railroad agent before joining the Secret Service in 1958. He worked in the agency's Denver office for about a year, before joining the elite group of agents assigned to protect the president and first family.

Since his retirement, Hill has spoken publicly about the assassination only a handful of times, but the most poignant was his 1975 interview with Wallace, during which Hill broke down several times.

"If I had reacted about five-tenths of a second faster, maybe a second faster, I wouldn't be here today," Hill said.

"You mean you would have gotten there and you would have taken the shot?" Wallace asked.

"The third shot, yes, sir," Hill said.

"And that would have been all right with you?"

"That would have been fine with me," Hill responded.

In his 2005 memoir, "Between You and Me," Wallace recalled his interview with Hill as one of the most moving of his career.

In 2006, Wallace and Hill reunited on CNN's "Larry King Live," where Hill credited that first 60 Minutes interview with helping him finally start the healing process.

"I have to thank Mike for asking me to do that interview and then thank him more because he's what caused me to finally come to terms with things and bring the emotions out where they surfaced," he said. "It was because of his questions and the things he asked that I started to recover."

Decades after the assassination, Hill co-authored several books — including “Mrs. Kennedy and Me” and “Five Presidents” — about his Secret Service years with Lisa McCubbin Hill, whom he married in 2021.

“We had that once-in-a-lifetime love that everyone hopes for,” McCubbin Hill said in a statement. “We were soulmates.”

Clint Hill also became a speaker and gave interviews about his experience in Dallas. In 2018, he was given the state of North Dakota's highest civilian honor, the Theodore Roosevelt Rough Rider Award. A portrait of Hill adorns a Capitol gallery of fellow honorees.

A private funeral service will be held in Washington, D.C., at a future date.

FILE - Clint Hill, a member of the late First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy's secret service detail, speaks to the media after he laid a wreath on the JFK Tribute outside the Hilton Hotel, Friday, Nov. 22, 2013. (Joyce Marshall/Star-Telegram via AP, File)

FILE - President John F. Kennedy slumps down in the back seat of the presidential limousine as it speeds along Elm Street toward the Stemmons Freeway overpass in Dallas, Texas, after being fatally shot, Nov. 22, 1963. First lady Jacqueline Kennedy leans over the president as Secret Service Agent Clint Hill pushes her back to her seat. (AP Photo/James W. "Ike" Altgens)

FILE - President John F. Kennedy slumps down in the back seat of the presidential limousine as it speeds along Elm Street toward the Stemmons Freeway overpass in Dallas, Texas, after being fatally shot, Nov. 22, 1963. First lady Jacqueline Kennedy leans over the president as Secret Service Agent Clint Hill pushes her back to her seat. (AP Photo/James W. "Ike" Altgens)

WEST DES MOINES, Iowa (AP) — Sgt. 1st Class Nicole Amor was just days away from returning home to her husband and two children when a drone strike at a command center in Kuwait killed her and five other U.S. service members.

“She was almost home,” her husband, Joey Amor, said from their home in White Bear Lake, Minnesota, on Tuesday. “You don’t go to Kuwait thinking something’s going to happen, and for her to be one of the first – it hurts.”

Amor was one of four U.S. soldiers killed in the Iran war on Sunday and identified Tuesday by the Pentagon; two soldiers haven't yet been publicly identified. The members of the Army Reserve worked in logistics and kept troops supplied with food and equipment.

They died just one day after the U.S. and Israel launched its military campaign against Iran. Iran responded by launching missiles and drones against Israel and several Gulf Arab states that host U.S. armed forces.

Those killed also included Capt. Cody Khork, 35, of Winter Haven, Florida; Sgt. 1st Class Noah Tietjens, 42, of Bellevue, Nebraska; and Sgt. Declan Coady, 20, of West Des Moines, lowa, who was posthumously promoted from specialist. No other names were released.

“These men and women all bravely volunteered to defend our country, and their sacrifice will never be forgotten,” Army Secretary Daniel Driscoll said.

All were assigned to the 103rd Sustainment Command, which provides food, fuel, water and ammunition, transport equipment and supplies.

“Sadly, there will likely be more, before it ends. That’s the way it is,” President Donald Trump said of deaths.

Coady had just told his father last week that he had been recommended for a promotion from specialist to sergeant, a rank he received posthumously.

He was one of the youngest people in his class but seemed to impress his instructors, his father Andrew Coady said Tuesday.

“He was very good at what he did," he said.

Coady trained as an information technology specialist with the Army Reserves and was studying cybersecurity at Drake University in Des Moines. He was taking online classes while in Kuwait and wanted to become an officer.

“I still don’t fully think it’s real,” his sister Keira Coady said. “I just remember all of our conversations about what he was going to do when he came back.”

Amor, 39, was an avid gardener who enjoyed making salsa from the peppers and tomatoes in her garden with her son, a senior in high school. She also enjoyed rollerblading and bicycling with her fourth-grade daughter.

A week before the drone attack, Amor was moved off-base to a shipping container-style building that had no defenses, Joey Amor said.

“They were dispersing because they were in fear that the base they were on was going to get attacked and they felt it was safer in smaller groups in separate places,” he said.

He last spoke to her about two hours before she was killed. He said she was working long shifts and they had been messaging about her tripping and falling the night before.

“She just never responded in the morning,” he said.

Khork was very patriotic and drawn from a young age to serving the U.S., his family said in a statement Tuesday.

He enlisted in the Army Reserve and joined Florida Southern College’s ROTC program.

“That commitment helped shape the course of his life and reflected the deep sense of duty that was always at the core of who he was,” said his mother, Donna Burhans, father, James Khork, and stepmother, Stacey Khork, in a statement.

Khork also loved history and had a degree in political science.

His family described him as “the life of the party, known for his infectious spirit, generous heart, and deep care for those who served alongside him and for everyone blessed to know him.”

One of Khork’s friends, Abbas Jaffer, posted on Facebook on Monday that he had lost the best person he had ever known.

“My best friend, best man, and brother gave his life defending our country overseas,” Jaffer said. Khork and Jaffer had been friends for more than 16 years.

Tietjens lived with his family in the Washington Terrace mobile home park in the Omaha suburb of Bellevue, Nebraska. He was married with a son, according to a Facebook page.

Tietjens earned a black belt in Philippine Combatives and Taekwondo and was “an instructor who gave his time, discipline, and leadership to others,” the Philippine Martial Arts Alliance said in a Facebook post.

On the mat and as a soldier, “he carried the same values: honor, discipline, service, and commitment to others,” the organization said.

Nebraska Gov. Gov. Pillen paid tribute to the family Tuesday.

“Noah stepped up to serve and defend the American people from foreign enemies around the world — a sacrifice we must never forget," he wrote.

“We are holding the Tietjens family close in our hearts during this unbelievably difficult time and will keep them in our prayers," he said.

Boone contributed from Boise, Idaho, and Toropin from Washington. Associated Press reporters Sarah Raza in Sioux Falls, South Dakota; Ed White in Detroit; Josh Funk in Omaha, Nebraska; David Fischer in Miami and Hallie Golden in Seattle contributed to this report.

Keira Coady talks about her brother, Sgt. Declan Coady, 20, of West Des Moines, Iowa, outside her home, Tuesday, March 3, 2026, in West Des Moines, Iowa. (AP Photo/Charlie Neibergall)

Andrew Coady and his daughter Keira, right, talk about his son, Sgt. Declan Coady, 20, of West Des Moines, Iowa, outside their home, Tuesday, March 3, 2026, in West Des Moines, Iowa. (AP Photo/Charlie Neibergall)

Keira Coady holds a photo of her brother, Sgt. Declan Coady, 20, of West Des Moines, Iowa, outside her home, Tuesday, March 3, 2026, in West Des Moines, Iowa. (AP Photo/Charlie Neibergall)

Keira Coady talks about her brother, Sgt. Declan Coady, 20, of West Des Moines, Iowa, outside her home, Tuesday, March 3, 2026, in West Des Moines, Iowa. (AP Photo/Charlie Neibergall)

This image provided by U.S. Central Command shows aircraft on the flight deck of the USS Abraham Lincoln (CVN 72) that are operating in support of the war in Iran, on Tuesday, March 3, 2026. (U.S. Navy via AP)