LEVELLAND, Texas (AP) — Dozens of researchers are chasing, driving and running into storms to collect fresh hail, getting their car bodies and their own bodies dented in the name of science. They hope these hailstones will reveal secrets about storms, damage and maybe the air itself.

But what do you do with nearly 4,000 melting iceballs?

Click to Gallery

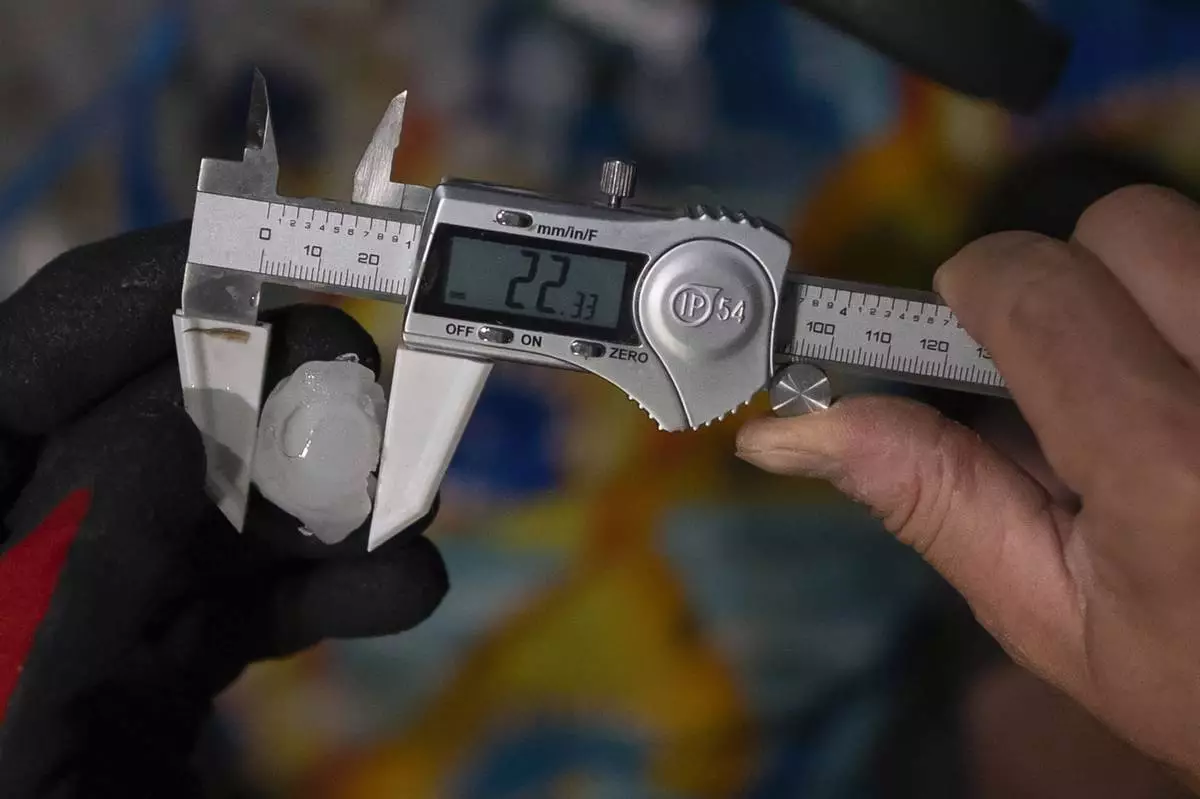

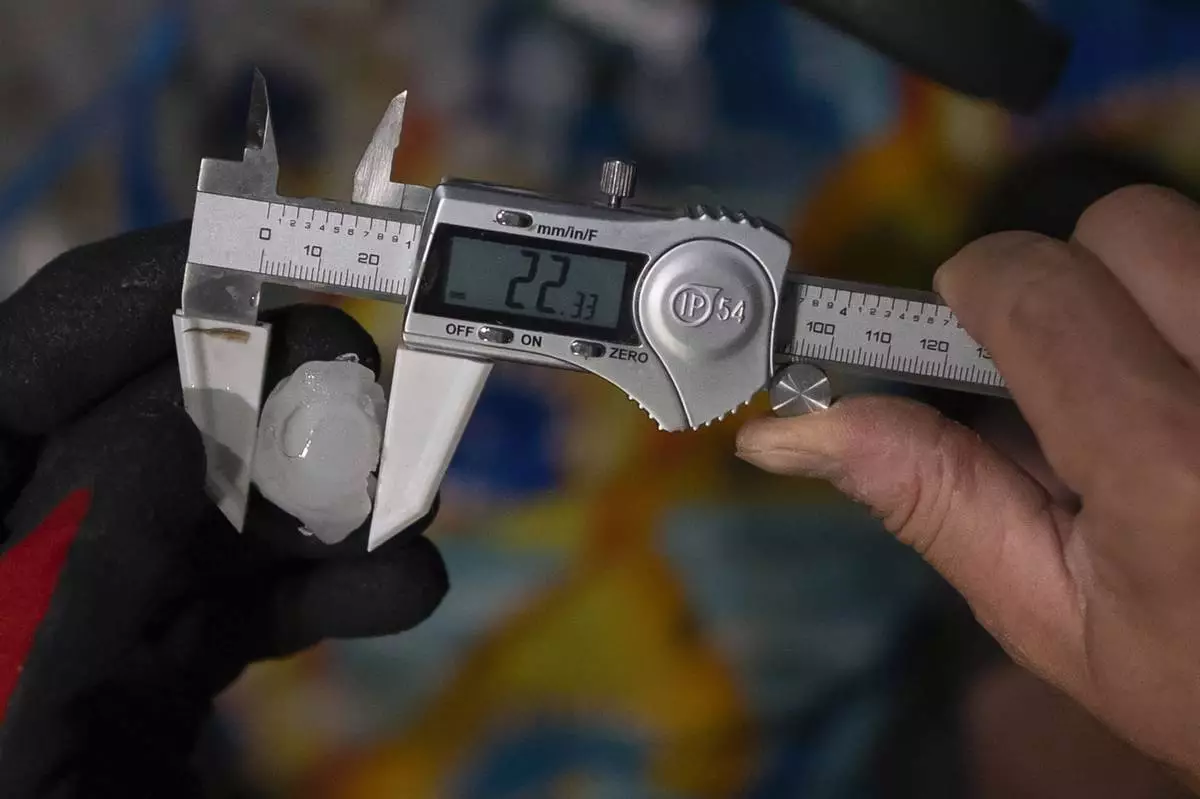

Jake Sorber measures hail in the Walmart parking lot during a Project ICECHIP operation Friday, June 6, 2025, in Levelland, Texas. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

Members of Project ICECHIP gather in the Walmart parking lot to measure, weigh and crush hail during an operation late Friday, June 6, 2025, in Levelland, Texas. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

Forensic engineer Tim Marshall measure a large hail shaped like a rose between the front seats of Northern Illinois University's Husky Hail Hunter during a Project ICECHIP operation Friday, June 6, 2025, in Morton, Texas. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

Tony Illenden turns to place a bag of hail he collected into a cooler in the backseat of the Northern Illinois University's Husky Hail Hunter during a Project ICECHIP operation Friday, June 6, 2025, in Levelland, Texas. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

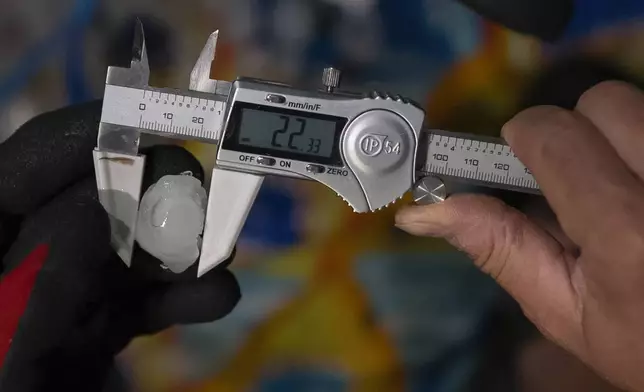

Tony Illenden crouches in a helmet and gloves outside Northern Illinois University's Husky Hail Hunter to scoop hail into a bag while in a hailstorm during a Project ICECHIP operation Friday, June 6, 2025, in Levelland, Texas. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

Jake Sorber crushes hail in the Walmart parking lot during a Project ICECHIP operation Friday, June 6, 2025, in Levelland, Texas. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

Jake Sorber prepares to crush hail in the Walmart parking lot during a Project ICECHIP operation Friday, June 6, 2025, in Levelland, Texas. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

Northern Illinois University's Husky Hail Hunter members Joey Toniolo, right, and Tony Illenden, back left, pick up hail while in a hailstorm during a Project ICECHIP operation Friday, June 6, 2025, near Morton, Texas. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

Tony Illenden crouches outside Northern Illinois University's Husky Hail Hunter to scoop hail into a bag while in a hailstorm during a Project ICECHIP operation Friday, June 6, 2025, in Levelland, Texas. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

A lot.

Researchers in the first-of-its-kind Project ICECHIP to study hail are measuring the hailstones, weighing them, slicing them, crushing them, chilling them, driving them across several states, seeing what's inside of them and in some cases — which frankly is more about fun and curiosity — eating them.

The whole idea is to be "learning information about what the hailstone was doing when it was in the storm,” said Northern Illinois University meteorology professor Victor Gensini, one of the team’s lead scientists.

It’s pushing midnight on a Friday in a Texas Walmart parking lot, and at least 10 vans full of students and full-time scientists are gathering after several hours of rigorous storm chasing. Hailstones are in coolers in most of these vehicles, and now it’s time to put them to the test.

Researchers use calipers to measure the width, in millimeters, of the hailstones, which are then weighed. So far after more than 13 storms, the biggest they found is 139 millimeters (5.5 inches), the size of a DVD. But on this night they are smaller than golf balls.

Once the measurements are recorded in a laptop, the fun starts in the back of a van with a shark-festooned beach blanket protecting the floor.

The hail is put on a vertical device’s white holder. Jake Sorber, a meteorologist at the Insurance Institute for Business and Home Safety, squeezes a hand grip about a foot above it and another white block comes crashing down, crushing the ice to smithereens. In the front of the van, Ian Giammanco, another IBHS meteorologist, records how much force it took to cause the destruction.

“That tells us about its strength,” Giammanco said.

Different teams do this over and over, with the debris littering vans. It’s all about trying to get good statistics on how strong the typical hailstone is. On this night, Gaimmanco and colleagues are finding the day’s hail is unusually soft. It’s surprising, but there’s a good theory on what’s happening.

“In hailstones we have layers. So we start off with an embryo, and then you’ve got different growth layers,” said Central Michigan University scientist John Allen. “That white growth is what’s called dry growth. So basically it’s so cold that it’s like super cold liquid water freezing on surface. ... All the gas gets trapped inside. So there’s lots of air bubbles. They tend to make a weak stone.”

But don’t get used to it. Less cold air from climate change could conceivably mean harder hail in the future, but more research is needed to see if that’s the case, Giammanco said.

“Damage from a hailstone is not just dependent on how fast and the exact amount of energy it has. It’s how strong are these hailstones,″ Giammanco said. ”So a really soft one is not actually going to damage your roof very much, especially an asphalt shingle roof. But a really strong one may crack and tear that asphalt shingle pretty easily.”

Mostly researchers grab hail to test after it falls, wearing gloves so as not to warm or taint the ice balls too much.

But to collect pristine hail and get it cold as soon as possible, there's SUMHO, a Super Mobile Hail Observatory. It's a chest-high metal funnel that catches hail and slides it directly down into a cooler. No contamination, no warming.

Most of these pristine hailstones go directly to a cold lab in Colorado, where they are sliced with a hot wire band saw. The different layers — like a tree's rings — will help scientists learn about the short but rapid growth of the ice in the storm, Gensini said.

Scientists will also figure out what's in the hail besides water. Past research has found fungi, bacteria, peat moss and microplastics, all of which helps researchers know a bit more about what's in the air that we don't see.

After weeks of collecting these ice balls, Central Michigan student Sam Baron sampled the fruit of his labors.

“It tastes like an ice cube,” Baron said. “It’s like the good ice that they serve at restaurants.”

The Associated Press’ climate and environmental coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

Jake Sorber measures hail in the Walmart parking lot during a Project ICECHIP operation Friday, June 6, 2025, in Levelland, Texas. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

Members of Project ICECHIP gather in the Walmart parking lot to measure, weigh and crush hail during an operation late Friday, June 6, 2025, in Levelland, Texas. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

Forensic engineer Tim Marshall measure a large hail shaped like a rose between the front seats of Northern Illinois University's Husky Hail Hunter during a Project ICECHIP operation Friday, June 6, 2025, in Morton, Texas. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

Tony Illenden turns to place a bag of hail he collected into a cooler in the backseat of the Northern Illinois University's Husky Hail Hunter during a Project ICECHIP operation Friday, June 6, 2025, in Levelland, Texas. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

Tony Illenden crouches in a helmet and gloves outside Northern Illinois University's Husky Hail Hunter to scoop hail into a bag while in a hailstorm during a Project ICECHIP operation Friday, June 6, 2025, in Levelland, Texas. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

Jake Sorber crushes hail in the Walmart parking lot during a Project ICECHIP operation Friday, June 6, 2025, in Levelland, Texas. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

Jake Sorber prepares to crush hail in the Walmart parking lot during a Project ICECHIP operation Friday, June 6, 2025, in Levelland, Texas. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

Northern Illinois University's Husky Hail Hunter members Joey Toniolo, right, and Tony Illenden, back left, pick up hail while in a hailstorm during a Project ICECHIP operation Friday, June 6, 2025, near Morton, Texas. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

Tony Illenden crouches outside Northern Illinois University's Husky Hail Hunter to scoop hail into a bag while in a hailstorm during a Project ICECHIP operation Friday, June 6, 2025, in Levelland, Texas. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

With the passage of the National Defense Authorization Act by the Senate on Wednesday, the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina is all but assured to become a federally recognized tribal nation.

The state-recognized tribe, whose historic and genealogical claims have been a subject of controversy, has been seeking federal recognition for generations. Congress has considered the issue for more than 30 years, but the effort gained momentum after President Donald Trump endorsed the tribe on the campaign trail last year.

“It means a lot because we have been figuring to get here for so long,” said Lumbee Tribal Chairman John Lowery moments after celebrating the victory in the capitol office of North Carolina Sen. Thom Tillis. “We have been second-class Natives and we will never be that again and no one can take it away from us.”

With federal recognition comes a bevy of federal resources, including access to new streams of federal dollars and grants and resources like the Indian Health Service. It also allows the tribe to put land into trust, which gives it more control over things like taxation and economic development, such as a casino.

In the 1980s, the Lumbee Tribe sought recognition through the Office of Federal Acknowledgement within the Interior Department, which evaluates the historical and genealogical claims of tribal applicants. The office declined to accept the application, citing a 1956 act of Congress that acknowledged the Lumbee Tribe but withheld the benefits of federal recognition.

That decision was reversed in 2016, allowing the Lumbee to pursue recognition through the federal administrative process. The tribe instead continued to seek recognition through an act of Congress.

There are 574 federally recognized tribal nations. Since the Office of Federal Acknowledgement was established in 1978, 18 have been approved by the agency, while about two dozen have gained recognition through congressional legislation. Nineteen applications ranging from Maine to Montana are now pending before the agency, with at least one under consideration by Congress.

Once federally recognized, the Lumbee Tribe would become one of the largest tribal nations in the country, with about 60,000 members. Congressional Budget Office estimates have found that providing the tribe with the necessary federal resources would cost hundreds of millions of dollars in the first few years alone.

“Hopefully, Congress will expand the pie in appropriations so that the other tribes, many of which are poor, don’t suffer because there’s suddenly such a larger number of Native Americans in that region," said Kevin Washburn, former assistant secretary of Indian affairs at the Interior Department and a professor at the University of California, Berkeley School of Law.

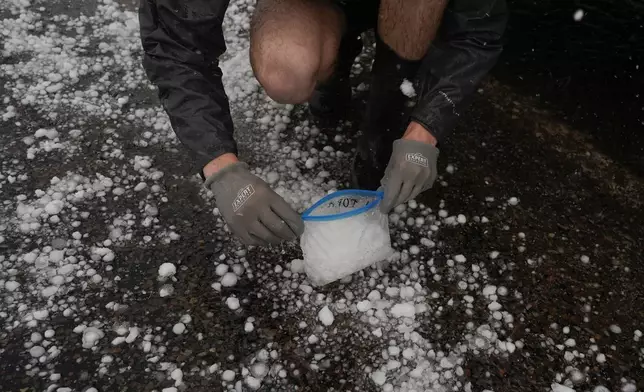

Over 200 Lumbee members gathered in a gymnasium in Pembroke, North Carolina, to watch the final Senate vote on television. They celebrated with shouts, raised hands and applause as the unofficial tally indicated the bill would receive final congressional approval.

Victor Dial held his 8-month daughter Collins at the celebration. Dial’s grandfather is a late former tribal chairman.

“He told us the importance of this, and he told us this day would happen, but we didn’t know when,” Dial said. “But we’re so glad it’s happening now, and I’m so glad my kids were here to see it.”

Not everyone in Indian Country is celebrating. The move has drawn opposition from some tribal leaders, historians and genealogists who argue that the Lumbee’s claims are unverifiable and that Congress should require the tribe to complete the formal recognition process.

“Federal recognition does not create us — it acknowledges us,” Shawnee Tribe Chief Ben Barnes, an opponent of Lumbee recognition, testified before the Senate last month. He warned against replacing historical documentation with political considerations.

Critics have noted that the Lumbee have a history of shifting claims and previously used different names, including Cherokee Indians of Robeson County, and say the tribe lacks a documented historical language.

“If identity becomes a matter of assertion rather than continuity, then this body will not be recognizing tribes, it will be manufacturing them,” Barnes told lawmakers.

The Lumbee Tribe counters that it descends from a mixture of ancestors “from the Algonquian, Iroquoian and Siouan language families,” according to its website, and notes it has been recognized by North Carolina since 1885.

While the Lumbee Tribe has received bipartisan support over the years, federal recognition became a campaign promise for both Trump and Democratic nominee Kamala Harris during the most recent presidential race.

“President Trump traveled to Robeson County and pledged to get federal recognition done. He kept that promise and showed extraordinary leadership," said Tillis, who introduced a bill to recognize the Lumbee Tribe.

Robeson County, where most Lumbee members live, has shifted politically in recent years. Once dominated by Democrats, the socially conservative area has trended Republican. The Lumbee Tribe's members in North Carolina are an important voting block in the swing state, which Trump won by more than three points.

In January, Trump issued an executive order directing the Interior Department to develop a plan for Lumbee recognition. That plan was submitted to the White House in April, and a department spokesperson said the tribe was advised to pursue recognition through Congress.

Since then, Lowery, the tribal chairman, has worked closely with members of Congress, particularly North Carolina Sen. Thom Tillis, and appealed directly to Trump. In September, Lowery wrote to Trump announcing ancestral ties between the Lumbee Tribe and the president's daughter Tiffany Trump, according to Bloomberg, which first reported on the letter.

“We are confident that with your continued support and advocacy, we will successfully achieve full federal recognition of our nation,” Lowery wrote.

Associated Press writers Gary Robertson in Raleigh, North Carolina, Allen Breed in Pembroke, North Carolina, and Jacquelyn Martin in Washington, D.C., contributed.

John Lowery, N.C. State Rep. and Chairman of the Lumbee Tribe of N.C., center, leads a toast to Sen. Thom Tillis, R-N.C., center, front right, as members of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina, celebrate the passage of a bill granting their people federal recognition, on Capitol Hill, in Washington, Wednesday, Dec. 17, 2025. (AP Photo/Jacquelyn Martin)

Austin Curt Thomas, 11, gets a celebratory fist bump from Sen. Thom Tillis, R-N.C., as he and his father Aaron Thomas, of Pembroke, N.C., join fellow members of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina, to celebrate after the passage of a bill granting their people federal recognition, on Capitol Hill, in Washington, Wednesday, Dec. 17, 2025. (AP Photo/Jacquelyn Martin)

People celebrate after passage of the National Defense Authorization Act by the U.S. Senate during a watch party hosted by the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina, Wednesday, Dec. 17, 2025, in Pembroke, N.C. (AP Photo/Allison Joyce)

People celebrate after passage of the National Defense Authorization Act by the U.S. Senate, during a watch party hosted by the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina, Wednesday, Dec. 17, 2025, in Pembroke, N.C. (AP Photo/Allison Joyce)

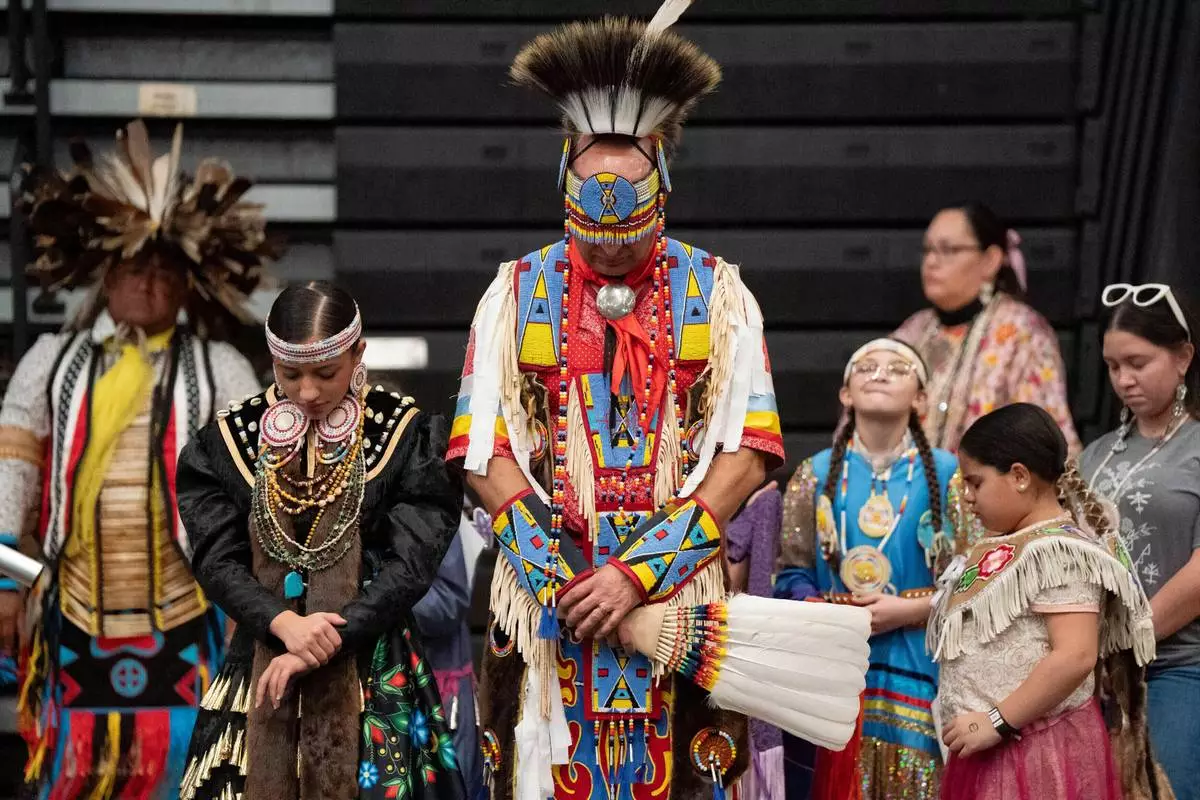

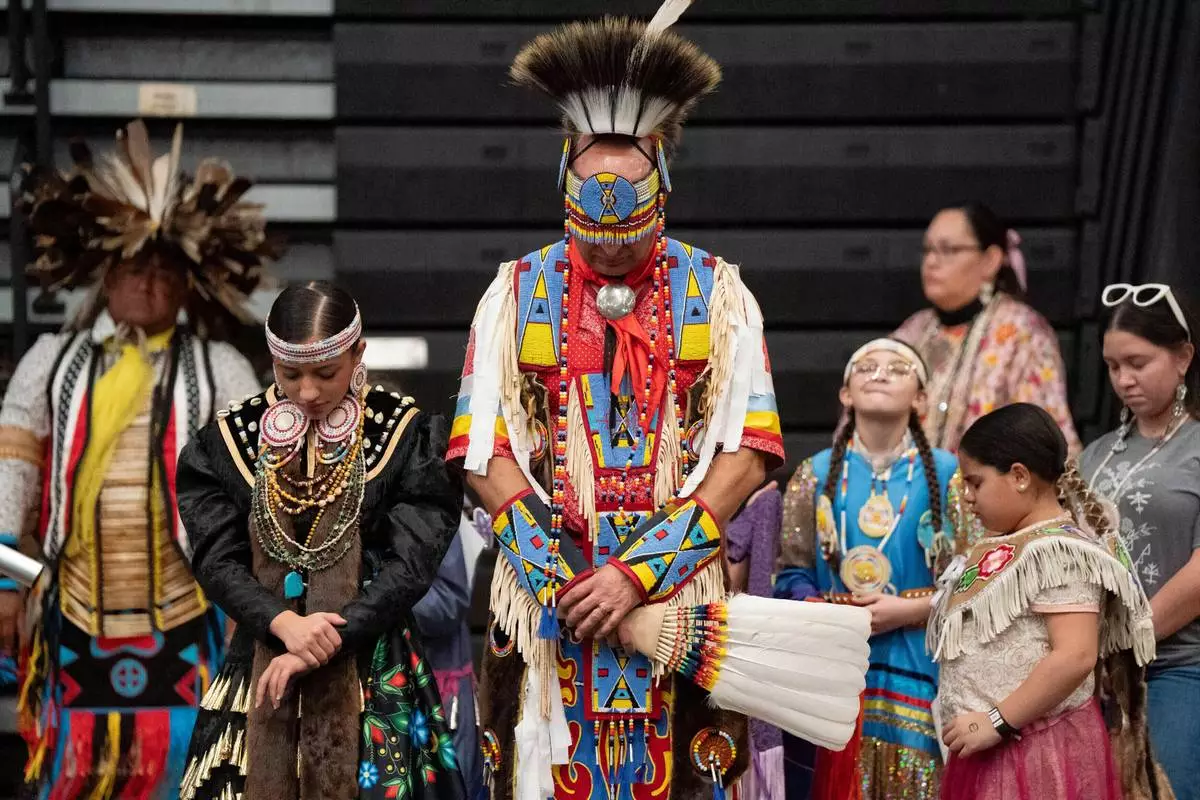

FILE - Members of the Lumbee Tribe bow their heads in prayer during the BraveNation Powwow and Gather at UNC Pembroke, March 22, 2025, in Pembroke, N.C. (AP Photo/Allison Joyce, file)

People sing while playing drums during a watch party hosted by the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina, Wednesday, Dec. 17, 2025, in Pembroke, N.C. (AP Photo/Allison Joyce)

People celebrate after passage of the National Defense Authorization Act by the U.S. Senate during a watch party hosted by the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina, Wednesday, Dec. 17, 2025, in Pembroke, N.C. (AP Photo/Allison Joyce)

People celebrate after passage of the National Defense Authorization Act by the U.S. Senate during a watch party hosted by the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina, Wednesday, Dec. 17, 2025, in Pembroke, N.C. (AP Photo/Allison Joyce)

People celebrate after passage of the National Defense Authorization Act by the U.S. Senate, during a watch party hosted by the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina, Wednesday, Dec. 17, 2025, in Pembroke, N.C. (AP Photo/Allison Joyce)