DUBAI, United Arab Emirates (AP) — Lights flicker, doors hang off their hinges and holes in the walls expose pipes in the apartment building where Hesham, an Egyptian migrant worker, lives in Dubai, an emirate better known for its flashy skyscrapers and penthouses.

His two-bedroom rental unit is carved up to house nine other men, and what he calls home is a modified closet just big enough for a mattress.

But now the government has ordered the 44-year-old salesman out of even that cramped space, which costs him $270 a month. He's one of the many low-paid foreign laborers caught up in a widespread crackdown by authorities in Dubai over illegal subletting.

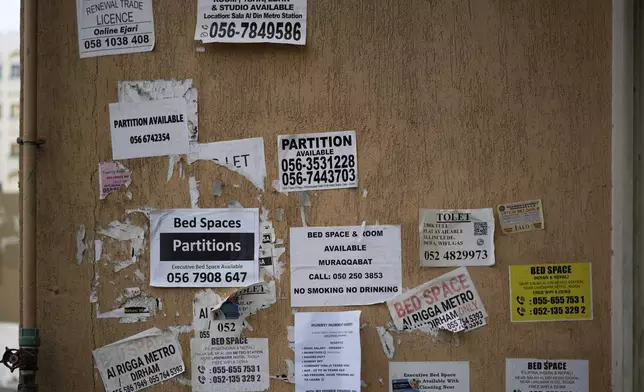

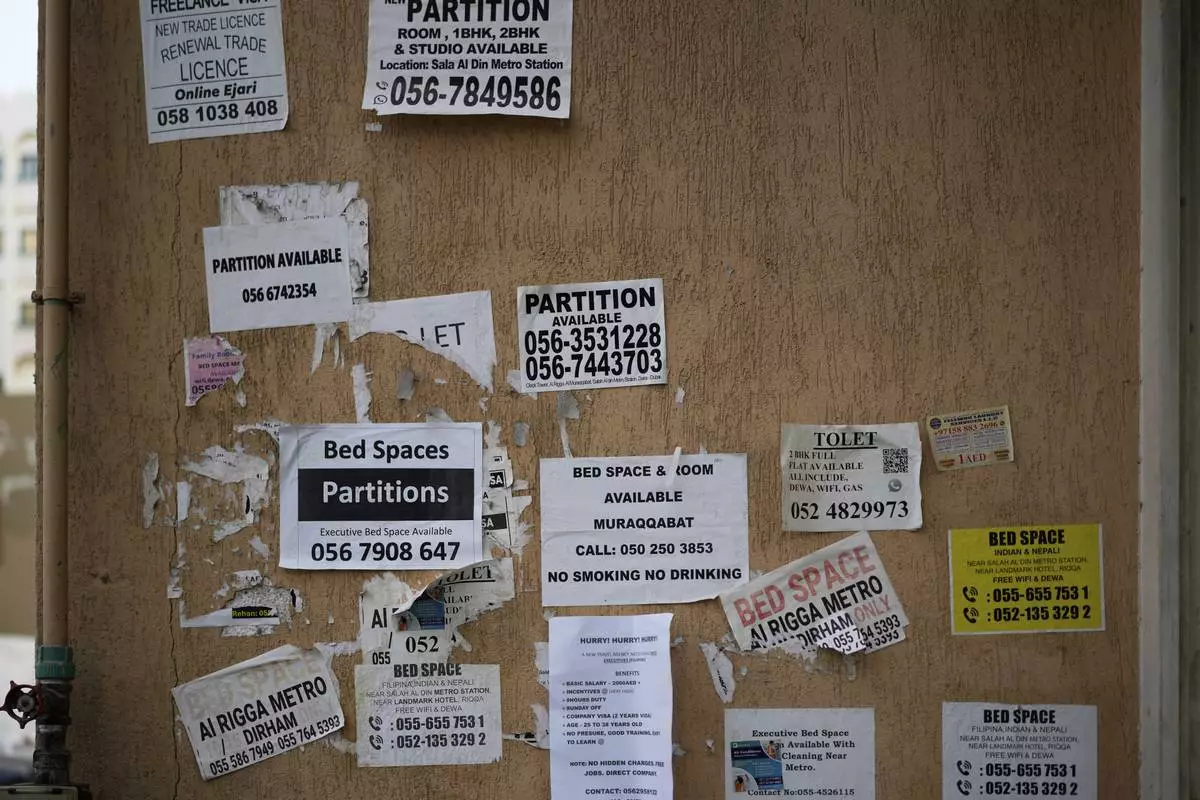

That includes rooms lined with bunk beds that offer no privacy but are as cheap as a few dollars a night, as well as partitioned apartments like Hesham's, where plywood boards, drywall and plastic shower curtains can turn a flat into a makeshift dormitory for 10 or 20 people.

After a blaze at a high-rise in June, Dubai officials launched the campaign over concerns that partitioned apartments represent a major fire risk. Some of those evicted have been left scrambling to stay off the streets, where begging is illegal. Others fear they could be next, uncertain when or where inspectors might show up.

“Now we don’t know what we’ll do,” said Hesham, who's staying put until his landlord evicts him. Like others living in Dubai's cheapest and most crowded spaces, he spoke to The Associated Press on condition only his first name be used for fear of coming into the crosshairs of authorities enforcing the ban on illegal housing.

“We don’t have any other choice," he said.

Dubai Municipality, which oversees the city-state, declined an AP request for an interview. In a statement, it said authorities have conducted inspections across the emirate to curb fire and safety hazards — an effort it said would “ensure the highest standards of public safety” and lead to “enhanced quality of life” for tenants. It didn't address where those unable to afford legal housing would live in a city-state that’s synonymous with luxury yet outlaws labor unions and guarantees no minimum wage.

Dubai has seen a boom since the pandemic that shows no signs of stopping. Its population of 3.9 million is projected to grow to 5.8 million by 2040 as more people move into the commercial hub from abroad.

Much of Dubai’s real estate market caters to wealthy foreign professionals living there long-term. That leaves few affordable options for the majority of workers — migrants on temporary, low-wage contracts, often earning just several hundred dollars a month. Nearly a fifth of homes in Dubai were worth more than $1 million as of last year, property firm Knight Frank said. Developers are racing to build more high-end housing.

That continued growth has meant rising rents across the board. Short-term rentals are expected to cost 18% more by the end of this year compared to 2024, according to online rental company Colife. Most migrant workers the AP spoke to said they make just $300 to $550 a month.

In lower-income areas, they said, a partitioned apartment space generally rents for $220 to $270 a month, while a single bunk in an undivided room costs half as much. Both can cost less if shared, or more depending on size and location. At any rate, they are far cheaper than the average one-bedroom rental, which real estate firm Engel & Völkers said runs about $1,400 a month.

The United Arab Emirates, like other Gulf Arab nations, relies on low-paid workers from Africa and Asia to build, clean, babysit and drive taxi cabs. Only Emirati nationals, who are outnumbered nearly 9 to 1 by residents from foreign countries, are eligible for an array of government benefits, including financial assistance for housing.

Large employers, from construction firms and factories to hotels and resorts, are required by law to house workers if they are paid less than $400 a month, much of which they send home to families overseas.

However, many migrants are employed informally, making their living arrangements hard to regulate, said Steffen Hertog, an expert on Gulf labor markets at the London School of Economics and Political Science. The crackdown will push up their housing costs, creating “a lot of stress for people whose life situation is already precarious,” he said.

Hassan, a 24-year-old security guard from Uganda, shares a bed in a partitioned apartment with a friend. So far, the government hasn’t discovered it, but he has reason to be nervous, he said.

“They can tell you to leave without an option, without anywhere to go.”

Dubai has targeted overcrowded apartments in the past amid a spate of high-rise fires fueled by flammable siding material. The latest round of inspections came after a blaze in June at a 67-story tower in the Dubai Marina neighborhood, where some apartments had been partitioned.

More than 3,800 residents were forced to evacuate from the building, which had 532 occupied apartments, according to a police report. That means seven people on average lived in each of these units in the tower of one-, two- and three-bedroom flats. Dozens of homes were left uninhabitable.

There were no major injuries in that fire. However, another in 2023 in Dubai’s historic Deira neighborhood killed at least 16 people and injured another nine in a unit believed to have been partitioned.

Ebony, a 28-year-old odd-job worker from Ghana, was recently forced to leave a partitioned apartment after the authorities found out about it. She lived in a narrow space with a roommate who slept above her on a jerry-built plywood loft bed.

“Sometimes to even stand up,” she said, “your head is going to hit the plywood.”

She’s in a new apartment now, a single room that holds 14 others — and sometimes more than 20 as people come and go, sharing beds. With her income of about $400 a month, she said she didn’t have another option, and she’s afraid of being forced out again.

“I don’t know what they want us to do. Maybe they don’t want the majority of people that are here in Dubai,” Ebony said.

The wall of a building is plastered with advertisements for inexpensive, partitioned housing in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, Friday, July 4, 2025. (AP Photo/Altaf Qadri)

Clothes dry on balconies of a residential building in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, Friday, July 4, 2025. (AP Photo/Altaf Qadri)

People walk past a concrete bench plastered with advertisements for inexpensive, partitioned housing in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, Friday, July 4, 2025. (AP Photo/Altaf Qadri)

A migrant worker hands out beauty salon pamphlets to passersby at a marketplace in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, Friday, July 4, 2025. (AP Photo/Altaf Qadri)

A modified closet where a migrant worker lives in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, is seen on Tuesday, July 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Gabe Levin)

Clothes dry on balconies of a residential building in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, Friday, July 4, 2025. (AP Photo/Altaf Qadri)